Texture of the Time

John Miller Protest Against Robert Muldoon, Auckland Airport 1977. Photograph. Courtesy of the artist

John Miller (Ngāpuhi) is a special figure in Aotearoa, having photographed protests and important events throughout the country from 1967 right up until the present moment. His work covers everything from the 1960s and 1970s anti-Vietnam war and anti-nuclear protests to the 1975 Māori Land March, 1977–78 Bastion Point occupation and 1981 Springbok Tour protests, as well as many more examples of civilian dissent. John uses the camera as a witness, capturing moments of collective voice in action, and he also honours the people who have led the charge for changes in thinking and our society. Looking at his work is like walking through our history backwards into the future. Curator Melanie Oliver sat down with activist John Minto and photographer Conor Clarke (Ngāi Tahu) to talk about John Miller’s work.

MELANIE OLIVER: John, as a long-term political activist, I wondered if you could talk about when you first met John Miller and when you became aware of his photographs.

JOHN MINTO: I can’t remember exactly when I first met him, but it would have been at Bastion Point during 1977 because I’d come to Auckland and the occupation began in January 1977. Every Sunday there was a big meeting up there with a couple of hundred people – inside if it was wet and outside if it was warm. John would have been there right the way through that, so at some point I would have got to know him. He’s like the wallpaper of the movement in a sense. He’s always there, recording what’s going on. His heart’s been with the movements that he has photographed and with the people that are at the forefront of those things. From my point of view, being part of the activist movement, he’s been one of those people who’s always been there, always with his camera and always keen to show you stuff that he’s done before and the stuff that’s taken now. He’s an ongoing witness, I guess, to the high jinks people get up to when they want to promote positive change.

MO: Looking over his extraordinary body of work from the past fifty years, there’s definitely a sense of him having been there through it all. Thinking back to those early days, to the 1970s when things were really active on the streets, did you think about documentary photography at that time and the role it played?

JM: No, I didn’t think about it at all. I think when you’re caught up in the moment, everything you see around you in that moment is what’s real, what’s happening, and you don’t think that maybe in twenty years’ time I’m not going to remember exactly what this was like. But of course John took a different point of view and when I look back at the things that he’s done, I’m just astonished at how our memories kind of blur things out, they smooth things over. But the texture of the time comes through in his photographs and they have a very powerful impact. You look at the Springbok Tour ones and you think ‘Wow’. The police were lined up like that and, my God, those batons – they did actually bash people. They hurt a lot of people really badly, and to see it in the crisp, clear light of day taken at the time is really moving.

CONOR CLARKE: They feel unreal, right, when you look at them? It doesn’t feel real.

John Miller Springbok Tour Police Red Squad,

Rintoul Street, Wellington and Springbok Tour Protestors, Pink and Brown Squads, Rintoul Street, Wellington 1981 Photograph.

Courtesy of the artist

JM: Doesn’t feel like New Zealand, does it? Young people are always really surprised when they see Merata Mita’s film Patu! about the Springbok Tour. They don’t believe that New Zealanders could have done that. Forty years after the tour, things are relatively settled, I suppose, compared to what it was like in the late-1970s when I first arrived in Auckland. You would go down Queen Street on a Friday night and there would be a march – you wouldn’t know what march it was going to be necessarily, but you’d go. And it would be women’s rights, it’d be anti-apartheid, it’d be anti-SIS spying on people – all these really vibrant movements were around and there was a real sense that our generation was provoking a lot of change. Certainly, we were very critical of the war generation, the Muldoon government and what he represented. There was a real upswelling of opposition and that boiled over in lots of protests in the late seventies and early eighties.

MO: Sometimes all the causes came together, didn’t they? I have seen some of John’s photographs of the Youth Progressive Movement, and there’ll be people with placards that advocate multiple things all at once. Dissent was really a part of that era. I feel like today we look at photography in a different way; if you haven’t photographed it and put it online, it didn’t happen… Conor, as part of a younger generation, do you see how photography has shifted since that time when it was eyewitness and not thought of as integral to the movement necessarily, to now when I think there is an element of utilising the camera. For example, I think of Ihumātao and how important it was that that documentation was disseminated on social media as well as through the usual press channels? Do you feel like it’s changed?

CC: Yeah, it’s quite a different way of sharing images. In previous times, you would have had to rely on places like Real Pictures Gallery, a physical exhibition space that was set up as a repository for people’s photographs, to bring them together in a way that might happen online through social media networks or websites now. I don’t know if you had anything to do with Real Pictures, John?

JM: We did. Absolutely.

CC: It was before my time, so I don’t really know that much about it. How do you talk about it? It must have been such a different time and maybe we’re a lot more aware now of the power that we have in terms of documenting these movements and sharing them online. But there’s also the point that we’re all photographers now, so we have a suspicion of the photograph as truth, or – I don’t know how to describe it, that…

MO: That when looking at a photograph, maybe you think about the surrounding conditions, the subjectivity and the framing?

CC: Yeah. You don’t necessarily know what everybody’s intentions are when there are so many photographers, whereas back then there would have been a lot fewer, John and a few others.

John Miller Hīkoi, Bastion Point, Auckland (detail from diptych) 2004. Photograph. Courtesy of the artist

JM: I think what’s different is that you’ve got photographs being shared around on all those social media platforms and they’re there as it’s actually happening. I think it’s a real challenge to people in power because they have their own narrative. The media and institutional powers have their own propaganda lines they want to put out, and yet the reality that people are watching unfold on their social media is quite different. Whether it’s Lukashenko in Belarus or even politicians here trying to push some particular line, people can see that “No, that’s actually not what happened.” Israel’s having a really hard time now because they’re trying to push these various narratives, and they’re very skilled at their propaganda. On the one hand, internally in Israel, they portray strength to their people – “We are the Government. We are in charge”. But to the outside world they want to portray a picture of weakness, and a need for support. So the immediacy of social media means that those narratives get sidelined often now. But, yeah, back then you had to wait for a photo exhibition. Like Real Pictures…

CC: How long did you have to wait with that? Weren’t they adding to the exhibition live? The one with the Springbok Tour, wasn’t that like a rolling thing where people were going in and exhibiting the photographs as it rolled out?

JM: Yeah, at the gallery.

CC: That was like a live blog. Obviously not ‘live’ live, but a few days later – process the film and then add images…

JM: But it was also accessible only to a very small number of people, because it was in Central Auckland so you’d have to get on the bus and go into town and see it there. There was no such thing as the internet or cell phones or anything. Most people would only see it several months later when they did their bigger exhibition that went overseas, the big panels that went to Melbourne and then on to London and New York. Then you see the whole thing in a kind of a context which, if you’re actually in the moment, you don’t see.

MO: That shift in technology from using the old-school camera to digital, do you see that in the quality of the photographs? Can you see that technology shift?

CC: Well, perhaps, but really I just can see it because it’s of the time, so you can’t really separate that period where you could use film. But yes, it’s different. You photograph differently with film, although John was using small format which is a very accessible medium. You can take a lot of photos, and he did, right?

MO: Yes, until he ran out of film each time.

CC: Yeah, so you can take quite a lot of photos, but not to the same extent as a digital camera where you can just go and go...

JM: No, but when digital cameras first came in, John wasn’t keen on them at all for a long time. I’m not sure what he’s using right now, but for a long time he wouldn’t use digital. He said to me that if you’ve got a digital camera, well, you can click, click, click... But if you’ve got 35mm film, you’ve got to be disciplined about what you take a photo of and you think more about the framing. You think more about how you’re going to take that picture. That was the way he was used to doing it and, yeah, he certainly didn’t pick it up immediately, digital. He was very old school in that regard.

CC: I think he’s also the most resourceful person I’ve ever met, so I can’t imagine him ever wasting anything – like wasting a shot, just in case. Everything has to be useful and meaningful.

JM: I think every time he clicked the shutter, he would know what he was taking and he would know how it would turn out and that was the picture he wanted to take.

MO: He was also taking photos in series as well, I think. So often, there’s the two sides, like in that great shot over in lower Rintoul Street in Wellington where you have the police on one side and the protesters on the other, very intentionally taken as against each other.

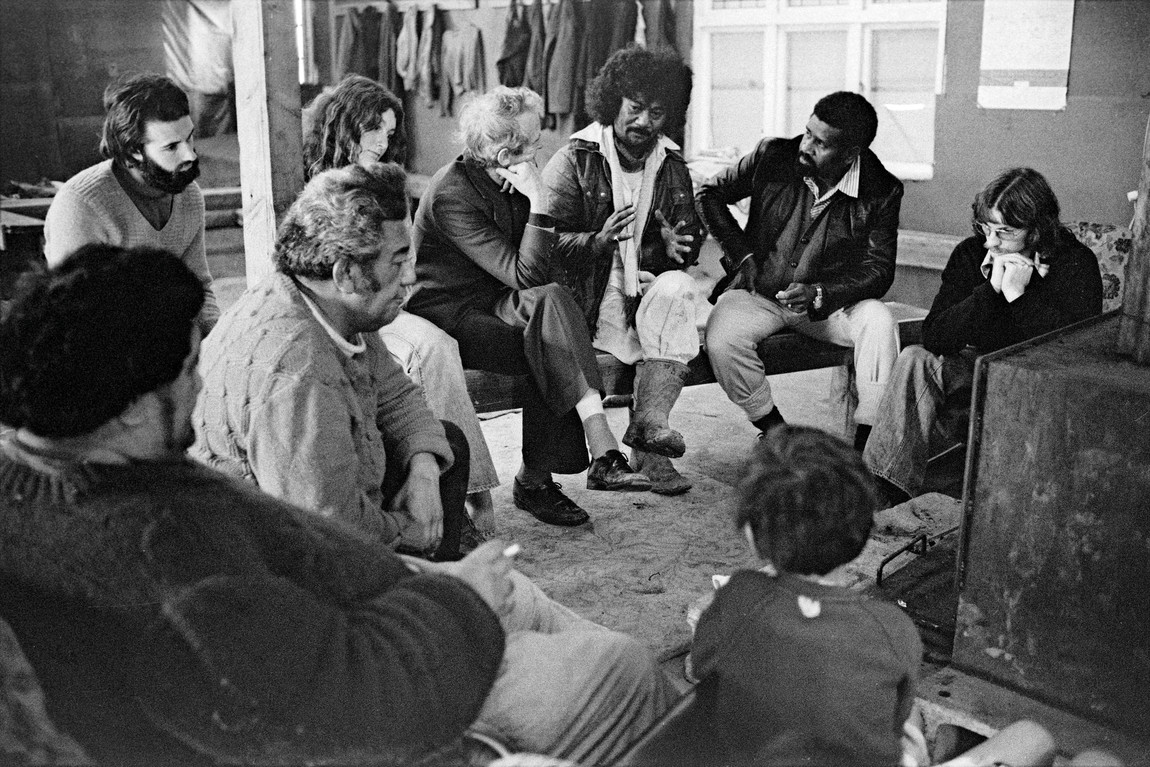

John Miller Takaparawhau Bastion Point Arohanui interior, including Reverend George Armstrong, Colin Clark, Father Walter Lini, Phil Goff 1977. Photograph. Courtesy of the artist

JM: I look back at some of his earliest stuff, taken when Ngā Tamatoa had their Tent Embassy at Parliament, and you see some of the photos up there on the steps of Parliament and all of those people he took photos of are now very well-known figures in the New Zealand establishment. No, that’s not true. ‘The Establishment’ is not right, but they’re very well-known figures. People who turned into politicians were leading public servants and what have you, but to see them in that context there is amazing.

MO: You can watch people growing up over time as well.

JM: Yeah.

MO: What has astounded me is John’s memory of events.

JM: Yeah. Look, he can tell you not just through his photos, but he’s just got an incredible memory. He remembers...

CC: Everything. He never forgets anything, names, dates, places, things.

JM: Yeah, and “When was the last time these two people were together?” that kind of thing.

CC: I think that’s what it’s about, that thing you mentioned, the backwards/forwards, cyclical. It’s the relationships. Watching people grow.

JM: Whenever he goes into a meeting now people gravitate towards him, because he’s a great raconteur of the stories behind the various movements. He can tell you the story behind each one of these pictures, and there’s a lot of humour in it and a lot of insight, a lot of understanding. He really engaged with the whole process as he took his photos, engaged with the issue, engaged with the people, recorded these really important events.

MO: How do you think it would have been if we didn’t have those records?

JM: Well, if you’d asked me forty years ago, I would have said, “Oh, well. You know, that’s just the way it was”. But of course now I can see the huge importance of it. Every time I look at the film Patu! for example, it was so important for New Zealanders to see the country the way it actually was and these pictures are the same.

MO: It gives a bit of hope, doesn’t it, that things can change?

JM: Yeah.

MO: A bit.

JM: Well, when you look back at when he started taking photographs with Ngā Tamatoa on the steps of Parliament, those people were regarded as real radicals right out on the fringe. And yet what they’re saying is absolutely mainstream today, or rather, what is mainstream today reflects what they were saying forty years ago.

CC: At last.

JM: We’re moving in the right direction now, and this is an indication of where we’ve come from.