Driving Without a Licence

Peter Robinson in conversation with Tony de Lautour

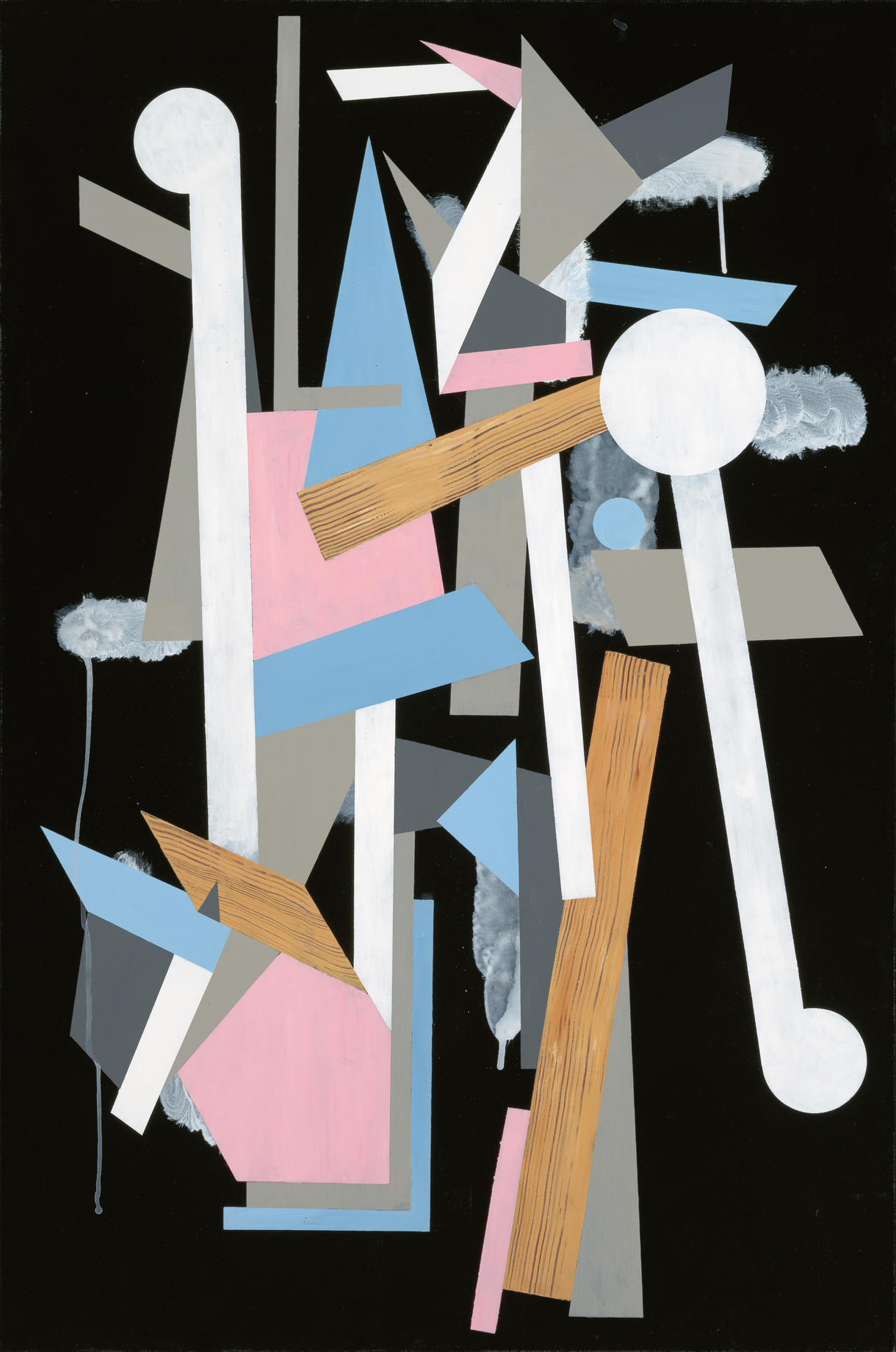

Tony de Lautour’s Colombo Street studio c.1993. Photo: Shaun Murphy. Image courtesy Tony de Lautour

Peter Robinson: I may be wrong about this, but I believe that we were the last generation to experience the primacy of painting at art school. What I mean by this is that when we were at Ilam, students had to compete to get into departments. As crazy as it sounds now, there was a very clear hierarchy: painting was the most popular discipline and afforded the most esteem, sculpture second, then film, print, design and photography somewhere down the line. Can you remember why you ended up choosing sculpture? And furthermore why you ended up being a painter? Do you think your training as a sculptor affected the way you think about or approach painting that is different to someone who was trained formally as a painter?

Sculpture studio, University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts, 1986. Tom Taylor, Steve Crene, Peter Robinson, and Claire Cosson. Image courtesy of Tony de Lautour

Tony de Lautour: I went to art school with a view to being a painter, but in our first year I found I was more interested in sculpture. We had an excellent sculpture tutor, Richard McIlroy, and that influenced my decision too.

It is crazy to think that there was a clear hierarchy and division between departments at the time. It did help that for two years you could study your major and then do a day of another subject – I chose painting with John Hurrell as lecturer. By my final year I’d become disillusioned with art school and our lecturer Tom Taylor, who at times was a good teacher with a good eye, but he wasn’t a practising artist and seemed more interested in his architectural projects. You’ll probably remember this also: he would arrive at school in the morning, say a few words to his students then leave for the university staff club at lunchtime, either not returning or coming back drunk and sitting in his office. His input was helpful when he was present; he was able to reduce a work down to its essence and would just say “belt and braces” if he thought a student had overworked a piece.

In my final year, the head of painting, Riduan Tomkins, asked me to join the painting department. Tom Taylor’s response was, “Tell Tomkins to get fucked.” I realised then it was nothing to do with what the student might want, but two egotists trying to mess with the other’s department. In the end I stayed in the sculpture department. In many ways Tom did me a favour, as I saw some graduates from the painting department become immersed in a certain style and it meant I had to work out painting for myself. I was making formal abstract sculptures at university, but I was spending a lot of time working on my paintings at home. I was ready to leave about a year before the course finished and afterwards simply moved on, not wanting to dwell on the experience. After graduating, a few people (mostly ex art students) got angry that I was making paintings because I had a sculpture degree and not a painting degree, like I was driving without a licence. That just seems so funny now, that people reacted like that.

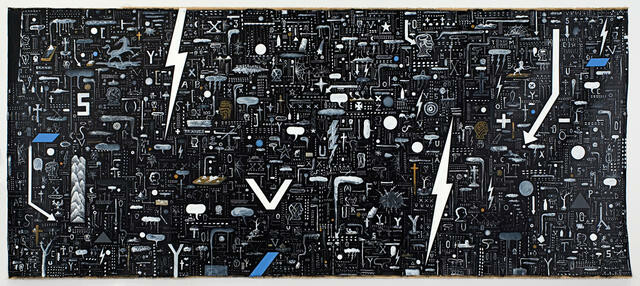

Looking back, the grounding in sculpture had a big influence on how I make paintings. I tend to build them up piece by piece, similar to making a construction. The tactile nature of paint on a surface interests me – another sculptural aspect. Many of my paintings look as though they could easily be built in three dimensions. Recently I did a series of work called Paintings for Sculptures, which I exhibited at Hamish McKay Gallery alongside small sculptural works. I’ve never really stopped making sculptures or objects – little talisman/ fetish-type objects, ceramics or constructions that are painted over – but it has been more a private aspect to my work, overshadowed by the paintings but generally made in relation to them.

PR: Still reflecting on art school, I think we probably went through the last days of a school-of-hard-knocks approach, by which I mean entry into Ilam and Elam was limited, students mostly taught themselves and some students were failed. I’m ambivalent about this because the environment was pretty patriarchal and very monocultural, but at the same time the difficulty of making it into and through the programme seemed to make the training meaningful. Do you have any thoughts on the days we went through and the current system at Ilam and art schools today?

TdL: The thought of failing students at any time, including in their final year, would be foreign to most lecturers these days, but was quite common when we were at art school. It did feel as though the axe was hanging over you, which made the students very competitive. The environment was quite tense at times but it forced us to be self-reliant, which was very helpful once you were out on your own after university. We were students in the era of no (or very low) fees, which changed shortly after we left to a user-pays system. I think the level of teaching now is probably far more professional, but maybe the expectation of some students is that they are paying for a degree and are therefore entitled to it. With the Labour government planning to introduce a new fee-free policy it may change the university environment again.

University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts, class of 1986. Image courtesy of Tony de Lautour

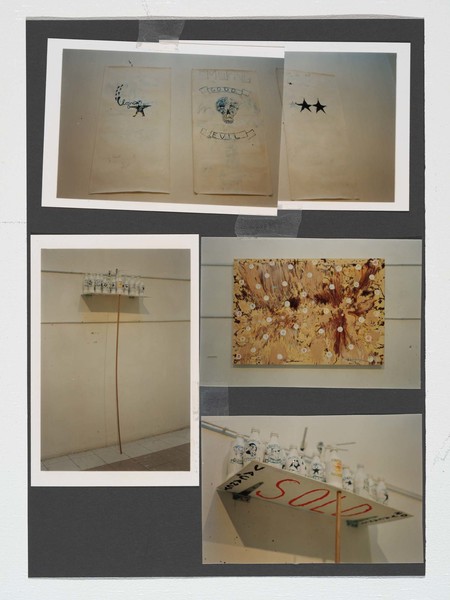

Tony de Lautour and Peter Robinson’s Top Shelf (1994) installed at the CSA. Image courtesy of Tony de Lautour

PR: You and I have enjoyed a good deal of recognition and success in our careers. We knew many equally talented people who didn’t get quite the same breaks. Luck is certainly a big part of a career, but as you know you can also make your own luck. I have the impression that you have mentored a good number of young artists over the years in Christchurch, Oscar Enberg being one I can think of. What sort of advice do you offer to young artists?

TdL: Yes, luck does play a big part in it. You get some opportunities, but also miss some. Many younger artists crave instant success and recognition, but in most cases it’s the last thing they need. Instead, they should just enjoy the freedom of making work for themselves. Artists who get success very early in their career often find it difficult to develop their work; they seem trapped by the work they’ve become known for. I had a few years in the wilderness after art school, which at the time seemed tough but enabled me to develop my own ways of working without the pressure and complications that recognition brings, and not be so worried about trying out different ideas later on. It helped me develop a tenacity to keep working without being concerned with how others view the work. Don’t worry if people don’t like what you’re doing – usually it’s just the opinion of a particular few people that are important to you that really matters. Having your peers working near you is great when you’re starting out. I have fond memories of the studio we shared with Séraphine Pick and William Dunning in Colombo Street for a few years when we were just out of university. But eventually you end up alone in a studio battling with yourself to make paintings.

There have been older, more established artists who have been supportive of me and my work. Quentin MacFarlane gave me a lot of practical advice, especially in regard to the craft of painting, stretching canvas, paint mediums etc. Richard Killeen, Julian Dashper and Billy Apple were always supportive and interested in what I was doing, all purchasing works early on in my career which meant a lot. Bill Hammond has always been very encouraging to me as an artist and a very good friend.

Having a good relationship with a gallery or curator and an art dealer can be important. The curators and dealers I’ve worked with over the years have, on the whole, been supportive. I’ve had long working relationships with Hamish McKay and Ivan Anthony; I started exhibiting with both galleries when they first opened. The Brooke/ Gifford Gallery started showing my work very early on, and I continued to show with them until the Christchurch earthquakes forced them to close. More recently I’ve been working with Nadene Milne. Ray Hughes in Sydney was always very insightful and astute about my work and what I was exhibiting in his gallery – maybe because he was seeing it from the perspective of being outside New Zealand looking in.

The conversation above took place over several emails between Tony de Lautour and fellow artist Peter Robinson.