Take the ‘A’ Train

An interview with Max Gimblett

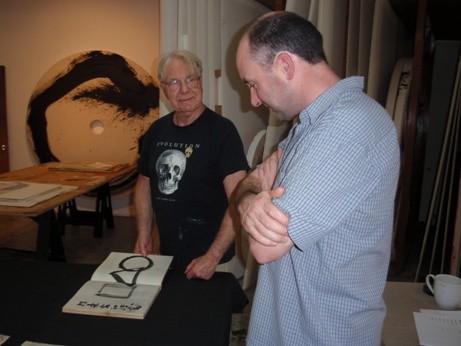

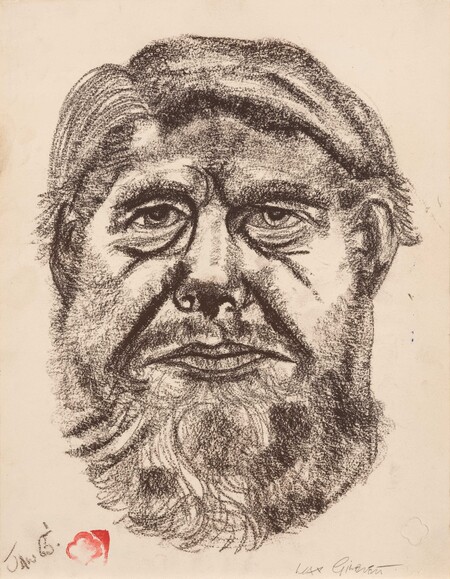

Max Gimblett in his studio, June 2020

Peter Vangioni: It’s late June, and you haven’t been outside for 16 weeks? Is that right? How are you and Barbara coping with the shelter in place order and are you able to work under these conditions?

Max Gimblett: Well, I’ve been out to put the garbage out twice a week—I cross the pavement and come back to the door. Some people are out there walking with their masks. Barbara is super cautious, you know because of our age, we can’t even come close to anybody. But we are doing very well in this lockdown, and have no plans to leave the loft.

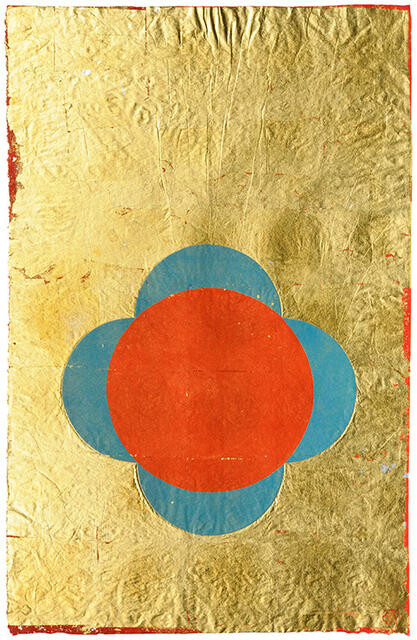

Max Gimblett Barbara Said “You Are a Painter” – In Toronto 1965. Conte crayon / Drawing Paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Gift

Barbara was recently awarded the Dan David Prize, a high honour and is working flat-out internationally, on Skype, Zoom and the phone... She is of course, the Ronald Lauder Chief Curator of the Core Exhibition of POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, in Warsaw.

I am attempting to complete my approximately 330 unique artist’s books. I’ve been making them since 1963. There are some I’ve worked in for fifty plus years and they are astonishing. Travel journals, sketchbooks, journals, artist’s books made in collaboration with amazing poets and writers, other painters... These books are made up of ink drawings, collages, gilding with precious metals, and stampings and have been bound by four different bookbinders over the years. They will find a home together as the Max Gimblett Artist’s Books Archive. They are a part of my legacy.

Let’s start at the beginning Max – simply put, how did you become an artist? Did you always know you would be one and was there anyone who encouraged you?

In 1962 I was in Toronto and was taken to a Ukrainian potter’s workshop; Roman Bartkiw, the potter, looked at me and said he needed an apprentice. I asked him what the deal was, he said I would work for him five or six days a week, eight hours a day, I would not get paid anything and after my first year he would let me make some pots of my own. I instantly said “I’m your man!” Two years later Barbara named me an artist when she came home from the University of Toronto one day and found me staring at a red Conté crayon drawing of myself I had done looking in a mirror, Barbara said you are a painter, and I said “Yes, I am”. That drawing which is one of my finest, is now in the Christchurch Art Gallery collection.

Did you travel much before Toronto, and was there any interest in art at that time?

I visited England in 1956–57 and then again 1959 to 61. Of course I wasn’t an artist at this stage, I was a textile man. The first trip I was a management trainee for Courtauld’s, the rayon manufacturer, and the second trip I was a coffee boy and came close to signing a lease for a Wimpy franchise – I thought I wanted to be a restaurant owner.

I was going to the Tate Gallery, and I discovered Salvador Dalí, he had a permanent exhibition in the basement, and I fell in love with Dalí. I was going to museums in London, and by the time I got to America I was going to museums all the time. In my early years the Auckland War Memorial Museum was my favourite, the ground floor was Māori and also there was, and still is, a display of Asian temple artefacts that includes ceramics and more importantly Buddhas. These Asian treasures fascinated me. In the basement once a week I used to go to anthropological films – I was educated by those films. I was going to Grafton Primary and I had a bicycle and I used to ride up to the Domain, so I’d go to the Museum once or twice a week. It was like a second home to me. It’s really in a way why I became an artist, because of that museum.

I left Auckland Grammar School after two years and became a salesman for Classic Manufacturing Co. selling ladies’ coats, suits and frocks. Whilst doing this I gained a three-year night course degree at Seddon Memorial Technical College and earned a certificate in Money, Banking and Finance as an Associate Member of the Institute of Management New Zealand. It was whilst working at Classic Manufacturing Co. that I discovered the Auckland Library, which is now the Auckland City Art Gallery, on Kitchener Street, and began reading New Zealand, American, Russian, French and English fiction and poetry. I have never stopped.

Max Gimblett For Len Lye – Radical Particles 1978. Sumi ink / Strathmore Aquarius Watercolour, Machine Made Cotton and Synthetic Paper. USA. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Gift

What drew you to the United States all those years ago? That was quite a different path to most New Zealand artists and you stuck it out. I imagine New York in the 1970s was a tough town to get by in.

I began painting and drawing in Toronto. I had been drawing for some time at night school and I had discovered Kimon Nicolaїdes’s The Natural Way to Draw, which became another one of my bibles. But I needed a proper introduction to painting. We moved to San Francisco and I studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institute. Meanwhile Barbara completed a BA and an MA at the University of California, Berkeley. I left the Institute after about three months and have maintained my own studio ever since. It became obvious to me that New York was the centre of the world’s contemporary art practices and market at that time. And being ambitious I needed to paint there. Our journey, Barbara’s and mine, took us to Bloomington Indiana, and Austin, Texas before arriving in New York in 1972. The city was very exciting in the seventies, and Barbara and I blossomed. For the first two years I stayed focused on artists and did not engage much in art-world business and so gained a solid network of artist friends. In those years I was a member of a group that met regularly in our various studios to critique works and engage in dialogue. I was in close contact with Jake Berthot, Phil Sims, Harvey Quaytman and David Reed, to mention only a few.

And Len Lye. How did you first meet Lye?

When we first arrived in New York I went to a reception hosted by the New Zealand consulate and there was this man in the corner, dressed very, very colourfully with this special cap on, sort of like Santa Claus. He was surrounded by women, and he was talking and I was absolutely captivated by him. So I went up to him and we arranged to meet. I went up to the loft in the Village that he and his wife Ann had. He was my teacher, I saw him about twice a week, I ran errands for him, I brought people to his studio and, unlike my father, he was totally uncritical, totally supportive of me.

So you were friends throughout the seventies?

It was like father and son. He thought I was a very good artist, I thought he was a master. I helped with things, I went to his country house and stayed with him and Ann, he was a mentor, an absolute original, one of the most original New Zealanders that ever lived. I’d put him up there with Sir Ed Hillary; he was really astonishing. I went to visit Len a few days before he died. On saying goodbye, I thought I was in for a hug. He shook my hand firmly, and as he walked away from me, he looked back over his shoulder and said “Sleepy time down south.” Ann later told me of the blinding light that came out of his body for hours after he lay dead.

You’ve been in New York now for nearly five decades, do you still feel connected to New Zealand and if so, how do you maintain that connection?

I remain, at heart, a New Zealander. I have never wavered. I have returned home around sixty times since I finally sailed off in 1959 and that speaks for itself. I have family in New Zealand and also many close friends I have met through being an artist.

Is there a particular location or place here that you feel strongly connected to?

I am an Aucklander, brought up in Grafton and schooled at Newmarket Primary, Grafton Primary, King’s Prep as a boarder, Auckland Grammar and Seddon Memorial College. My magical spot is in the Bay of Islands, Deep Water Cove, where I stayed safe during the polio epidemic.

I got my first rugby jersey at Grafton Primary when I was about ten years old. We played in bare feet. My senior year at King’s Prep I made the first fifteen, loose head prop, which remained my position over the years, although occasionally I was hooker. I played for 4A General at Auckland Boys’ Grammar.

Loose heads were quite rough weren’t they?

Oh yes, the game was tough in my years. I was a part of that.

Bruiser Gimblett?

When I left school I played for Auckland in the 6th grade. Went down to Hamilton and played Waikato. I was too small for the first grade. In England I played for Sidcup in Kent, I played in the second team and one day the prop in the first team was sick so I filled in for him and when I went home, every bone in my body was hurting. The guys were 100% tougher. They just crunched you.

My final game was at a Jewish summer camp in Ontario, Canada and I quickly realised I was over the hill and retired. Today I watch the All Black games, most international games and the weekly Premiership Rugby in England.

Oh and I follow all the New Zealand cricket games, the Black Caps. Martin Crowe was a very close personal friend of mine. My cousin Harold Gimblett (I was given his name Harold as my middle name) held most of the Somerset batting records, and maybe still does? I was once asked Martin how he prepared for a cricket match, and he said that he sat alone silently in a room with a towel over his head for an hour and played every stroke.

Are there any other places in the world you feel a strong connection to?

Yes Toronto – it’s where I became an artist and where I met my wife Barbara. I remain close to Toronto where her family live. I also have deep connections to Ahuahu, Sir Michael Fay’s Mercury Island, Arrowtown, Wellington, Barcelona and Paris.

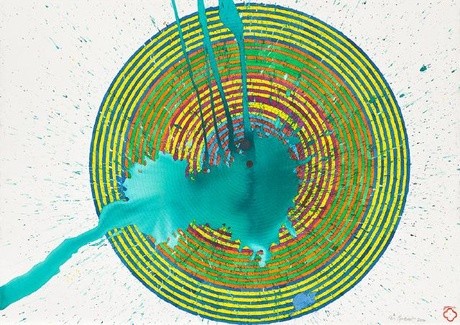

Max Gimblett the sound of one hand – 7 – 10/5/05 2005. Sumi ink / Belgique Cotton and Linen Handmade Paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Gift

What’s your new studio / home like? And was the transition from the Bowery to Broadway difficult?

We renovated an artist’s loft in an 1884 building in Soho and it is magnificent. Our dream space. In fifty-five years of marriage this is the first space we have worked and lived in that we renovated from scratch. The move was totally stressful, leaving our home and studio of forty-four years and packing everything up. It was exhausting, however we have been here almost a year now and love it.

One thing that really struck me when Jenny Harper and I were making selections for the Gallery gift back in 2010 were the ensō drawings – I was not really that aware of these as we haven’t had many opportunities to see your work here in Christchurch over the years before Nadene Milne opened a gallery. Can you tell us what significance the ensō and the circle have for you personally and in your practice?

Ensō, is perhaps the leading motif in Japanese calligraphy. It certainly has become mine. It took maybe fifteen years’ drawing before my ensōs became round – previously they were ovals or sort of one-sided squeezed circles as I misjudged my centre and ran towards the left or right side of the paper. Also I had not resolved my in and out, practice makes perfect. My drawing impulse shifted from School of Paris, headed up by Matisse and Picasso, to Japanese calligraphy in my Bloomington, Indiana studio in 1968/69. I was introduced to Zen calligraphy in San Francisco. I study with the Japanese masters of all ages, they come to my studio and instruct me when I evoke their name.

Ensō is the Self, living two fingers sideways below the navel in the stomach known as the Dantem. Also the Sun and the Moon, our eyes, our spinning globe, continuous time with no beginning and no end. I could go on and on. I always lead with this motif in my sumi ink workshops as a centring device. M. C. Richards’s book Centering was my bible as a potter. All about the centre which is one of the crucial keys to wheel-thrown pottery. It is said of the calligraphic masters that when they see your ensō they instantly know your spiritual development.

In The Brush of Things catalogue Barbara asks you about Rinzai Zen, koan study and calligraphy, I feel a little out of my depth here but could you give us explanation of the importance of these ideas, practices and notions to your practice?

In my early years in New York the book The Zen Koan by Isshū Miura and Ruth Fuller Sasaki came into my possession. I have studied it ever since. I know hundreds of koan – my personal one, given to me by my master Great Dragon, Michael Wenger, is “at every step the pure wind rises”. In 2006, after studying for some years with Great Dragon I took my vows at the San Francisco Zen Center. I am a lay Zen Monk with the name of Kongo Hitsu Kaku Shin. Diamond Brush – Awakened Heart.

Hakuin, the master who saved Rinzai Zen, taught from “the sound of one hand”. I teach from “what was your face before your face in your mother’s womb?” “No mind, all mind” derives from the conviction that if you clear your mind of all activity, and let go completely you will have your mind. “One stroke bone” refers to Chinese calligraphy brushes with bone handles and animal hair, usually fox, badger, dog or horse. The hundreds that I own are all horse hair. A further notion of my practice is “the in and the out”. This is the fully loaded brush stroke at its very beginning and the unloaded brush on the way out. Both entrance and exit must be decisive, vigorous and fully meaningful.

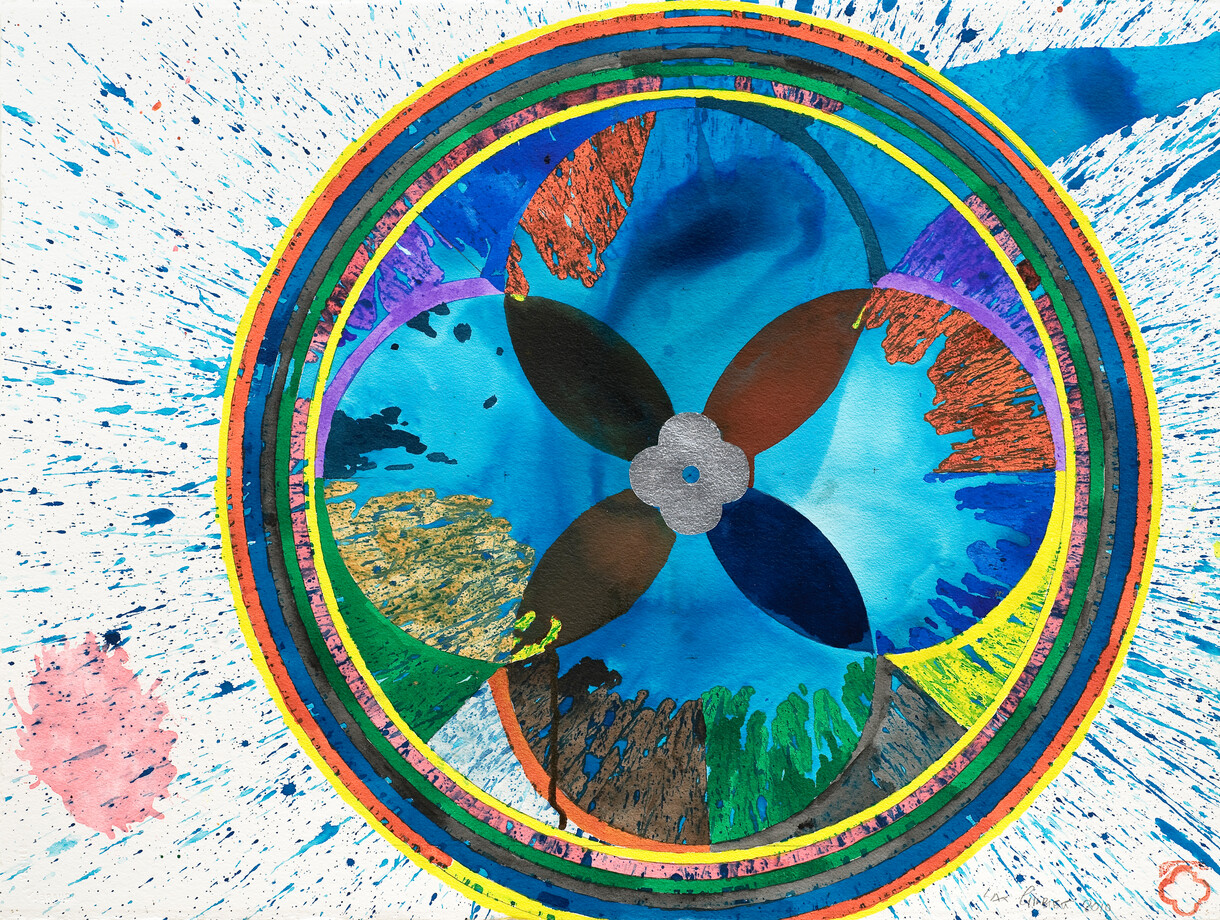

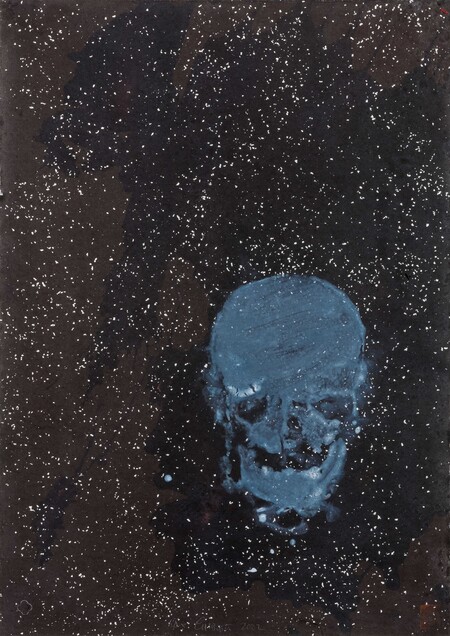

Max Gimblett Lost At Sea – 2 2002. Acrylic polymer on Japanese Kinkami silver-fleck 100% kozo handmade paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Gift

Is there a certain routine to your day in the studio?

I was born at dawn. I am a day person, not up to much at night. Basically I relax at night, after a full day in the studio, six days a week. Four days in the week I work in my studio with the painter Matt Jones, who is also my database manager. We have been together for twenty-one years. Matt and I have an endlessly deep relationship. Most studio assistants over the years have worked with me for around ten years, having originally shown up as interns from art schools and universities. Before moving on from the Bowery, Giovanni Forlino and Kristen Reyes-Marion were long-term dedicated assistants.

There are a few skulls in the gift, including the three beautiful Lost At Sea works, some of my personal favourites. So why skulls?

In 1983 the skull arrived in my work as a motif. I understand its presence as an element of my preparation for leaving my body. It is an aspect of one’s death. I have always regretted not living with my father’s and grandfather’s skulls, they seem wasted, destroyed or buried or discarded. I live with a woman’s skull I bought in Amsterdam many years ago. The skull is timeless and many churches around the world have vast collections of bones. In Japan it is possible to have a family member’s bones after cremation. A lot of paintings of artists in their studios, like Rembrandt, have a skull in the studio, and there is of course Hamlet.

It seems to me that you hold your works on paper to be just as significant as your larger paintings, do you consider them equals? Is there a relationship between them?

Yes, I approach each work of art as equal. The paintings and the drawings, the mandalas on paper, rich colourful ink and gilded, the black and white sumi inks, prints, screen prints, monoprints and lithography, ceramics, Spirit boxes, are all significant in their own right. They are not dependent on one another, they stand alone. Each articulates something particular to its medium. Each lives in their own tradition.

Max Gimblett spoke to curator Peter Vangioni in June 2020.