Rex Valentine potting in Bizen, Japan, 1977. Photographer unknown. Rex Valentine collection

A Passion for Clay and Pots

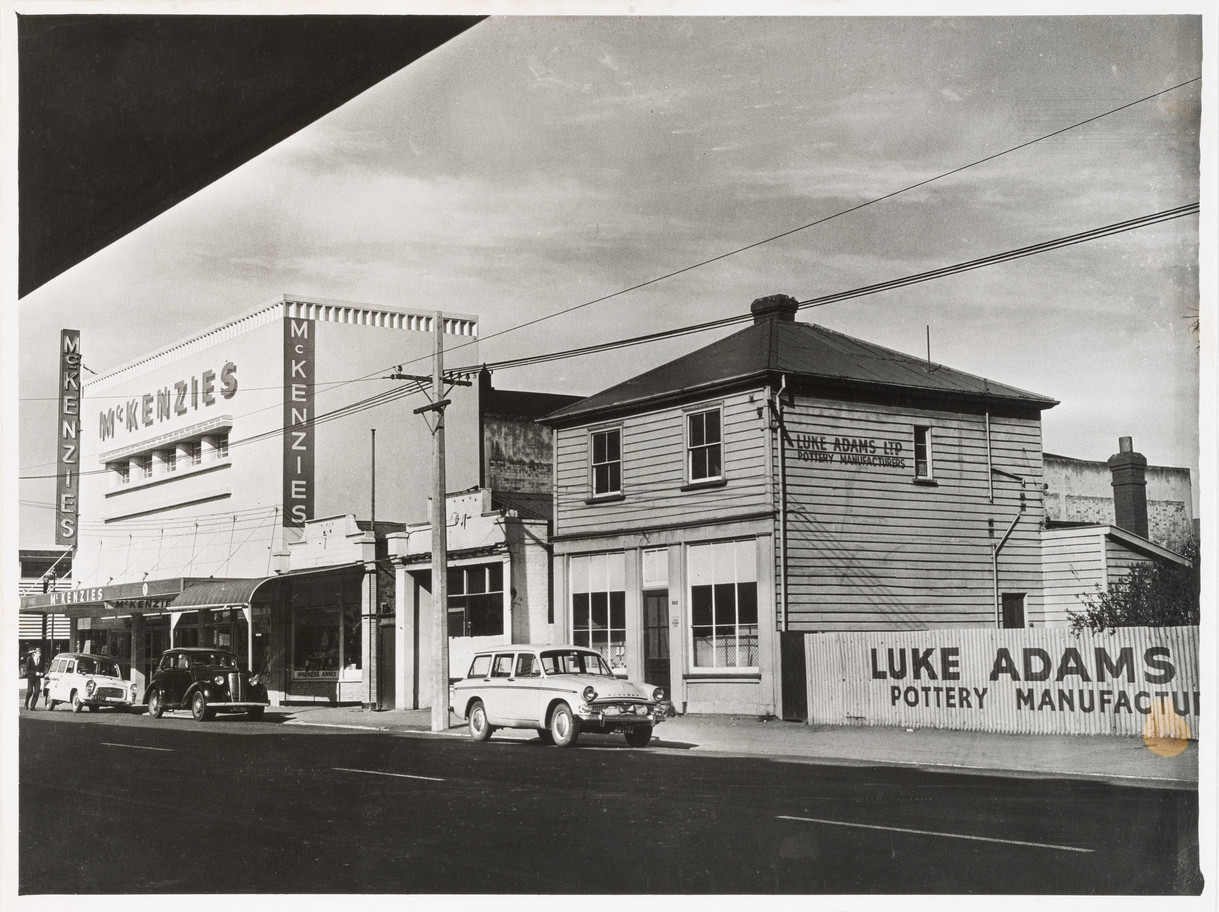

In recent months, retired potter and former president of the Canterbury Potters’ Association, Rex Valentine – a man passionate about clay – and art consultant Grant Banbury have been working behind-the-scenes in the Gallery alongside registration, curatorial and conservation staff. They’ve been assisting with an audit of a part of the collection that we’re excited to be working with more – the Gallery’s ceramics holdings.

Here Banbury and Valentine discuss the latter’s own production and involvement in pottery circles in Canterbury from the late 1960s to the 1980s; his time spent in studying pottery in Japan, and his involvement with pottery acquisitions during Brian Muir’s directorship of the Robert McDougall Art Gallery. The edited extracts that follow are from an interview recorded at Valentine’s home in Christchurch on 10 April 2021.

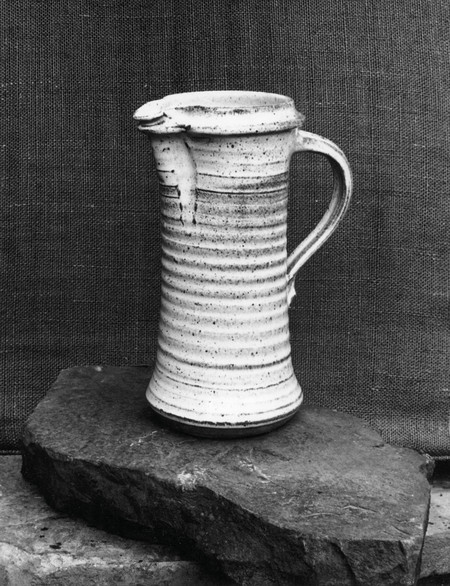

Rex Valentine Jug, stoneware, tin glaze 1976. Rex Valentine collection. Photo: Keith Nicholson

Grant Banbury: Tell us about your background, Rex.

Rex Valentine: I was born in Christchurch and brought up in the Beckenham loop. I attended Beckenham Primary then Cashmere High School, where young art teachers Quentin MacFarlane and Alan Pearson had a big influence on me. I wasn’t good at drawing, but I was good at mobiles...

GB: What got you connected with clay?

RV: I was around twenty, and had a girlfriend who lived near Nelson, in Moutere, and when out one day we stopped at Jack Laird’s pottery… I was very new to pottery myself, so I hadn’t really taken notice of the whole process – kneading clay, throwing a pot and forming it sort of sparked me a little bit. We also went up to Crewenna Pottery and looked at their pots – I could see the difference – and we visited potter Mirek Smíšek. He was charismatic and we struck up a relationship which lasted a good few years.

GB: Looking back at New Zealand’s studio pottery movement, the 1970s were the heyday. Many potters moved to the country, made kilns, developed a rural lifestyle, often with young families.

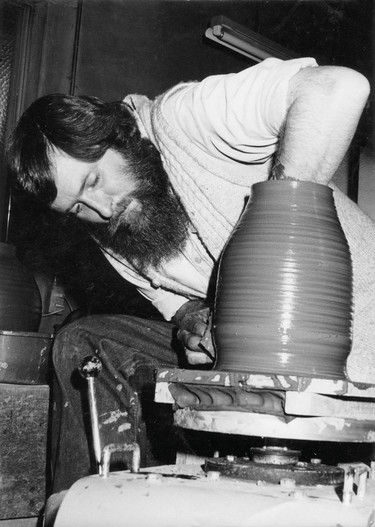

RV: True, true – it was definitely a lifestyle! Inspired, I came back to Christchurch and started to draw pottery shapes. I designed several pots, a coffee pot and a wine pot. Marie Tothill was teaching pottery at Christ’s College but she was too busy to help, so she put me in touch with Denise Welsford who gave me private lessons. Well, I had good throwing ability – I had the strength in my arms and shoulders, I could centre the clay [on the wheel] and do all the basics and if you’re one-on-one you can focus. I was able to fire pots in her small electric kiln, and she introduced me to potter Michael Trumic who took me under his wing. He built a kiln for Denise and I picked up the whys and wherefores of it, which was good for me because I liked that technical side… making sure the kiln works correctly; making sure the soot from it didn’t settle on the neighbour’s washing. Denise has now been my partner for over forty years.

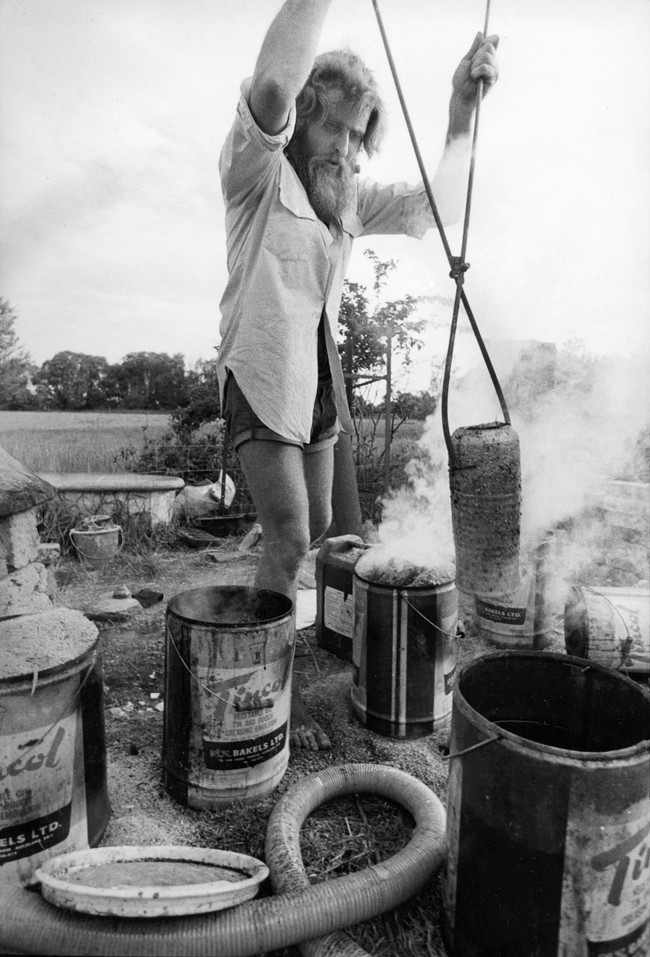

GB: Have you ever built a kiln yourself?

RV: I bought my first property out at Halswell, a little farm cottage of English design, and I built my own kiln. I had a friend who worked for McSkimmings [pottery works], and we got the fire bricks from there.

GB: What scale was the kiln – how big relative to the height of a person?

RV: Oh, a bit lower than the height of a person, the inside would be about a metre by a metre and just over a metre tall.

GB: How long were firings and what temperatures did it reach?

RV: It ran on diesel… firings were about 12 to 18 hours and 1,320°c, which turned the clay into stoneware.

GB: You recently gave the Gallery a beautiful stately jug made in the 1970s; where did you get the inspiration for this form?

RV: I found a book on English Medieval jugs by Rackman and adapted the shapes to my own form. You can’t really copy… you always end up doing your own version.

GB: The jug is a gutsy statement I think.

RV: Oh, definitely. What I had in mind was turning it into a piece with a sculptural presence.

Rex Valentine Stoneware vases, tin glaze 1976. Rex Valentine collection. Photo: Keith Nicholson

Barry Brickell Loco boiler (with alternative stacks for warming the hands) 1976. Terracotta. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1976

GB: What domestic ware did you make?

RV: I really enjoyed making bowls, teapots and vases; I made a lot. And I find it amazing that people who bought bowls from me fifty years ago still count them as favourites, using them on a daily basis for muesli, porridge or soup or whatever. That brings me joy. I used to make a lot of dinner sets, with a main meal plate, side plates, soup and dessert bowls, maybe some mugs, whatever, to go with them.

GB: Was that earning you anything? And where were your outlets?

RV: Well, it definitely wasn’t earning enough to live on, so we [Denise and I] augmented our income with teaching. We were both members of Canterbury Potters and we taught pottery at Shirley Intermediate and other places. Our outlets included Several Arts in Christchurch, Décor in Timaru, Alicat in Auckland… we sent work to other centres too.

GB: Looking back through a 1975 New Zealand Potter magazine, it lists numerous local teaching facilities: Risingholme Community Centre, Springfield Road craft centre, Shirley activities club, Mt Pleasant pottery club, Bishopdale pottery class. And the schools; Riccarton High and Shirley Intermediate… it sounds like a lot of activity. I remember visiting Several Arts in Colombo Street – an important craft outlet that held exhibitions upstairs.

RV: That was started by Michael and Victoria Trumic and others.

GB: Yes. Can you tell me about your involvement in Studio 393?

RV: We found an old flour-loft upstairs at 393 Montreal Street. Denise, Michael Trumic, Margaret Higgs (later Ryley), Frederika Ernsten and myself started it… later, Lawrence Ewing joined… it opened in 1975.

GB: I have clear memories of it as a schoolboy, and I still have pots bought there made by Margaret and Lawrence. Studio 393 got me hooked and was the beginning of my ceramics collecting, which continues today. Were classes held there?

RV: We did have classes and we held schools too. It wasn’t just a gallery, it was a melding of minds and we all learned off each other and interacted. That’s unusual for a shop, but we looked at it from another way. Philip Trusttum showed with us reasonably regularly – he was a good friend of Michael’s and was in The Group at that stage, and sort of starting off. Doris Lusk, fabric artist Robyn Royds and Pamela Maling; woodturners, weavers and others… you showed there too.

GB: What people don’t realise about The Group is how much pottery and craft were shown. You know; weaver Ida Lough, pottery by Len Castle, Juliet Peter and Roy Cowan, and works from these shows went into the McDougall collection.

RV: Well, this is it. Several artists moved equally and happily between pottery, drawing, painting, sculpture. They were multi-faceted people who took on pottery, which has always been a bit of a poor relation to other arts. You can see from the 1970s and 1980s things were really moving on.

GB: The other day you showed me a photograph of an Akaroa exhibition you were included in, with an incredible 150 pieces!

RV: They used to be very well organised in Akaroa! They put you up, fed you, watered you and wined you, and you brought your pots over, you were there at the opening and you talked to people, you gave schools there. We probably sold a good fifty per cent of that show.

GB: And from the late 1960s the Robert McDougall Art Gallery started acquiring pots...

RV: Well, it was all very new. When Brian Muir came along to 393 and bought the odd pot, he asked for help. There wasn’t a clear structure to their pottery acquisitions. But by that stage we knew the other potters intimately. We used to travel New Zealand to national pottery shows, we used to go en masse really. We’d all discuss and see each other’s pots. I selected Alan Caiger-Smith works for the gallery.

GB: Let’s talk about Barry Brickell’s wonderful terracotta train, Loco Boiler (with alternative stacks for warming the hands). It’s a fantastic work – I understand you were involved in selecting it for the collection.

RV: Brian asked Denise and myself to look for a good piece by Barry, who had sent two or three pieces down for a national exhibition here at the CSA. Barry was totally besotted with steam trains, they ruled his life, and he’d made a large boiler with three interchangeable stacks on it so you could change the visual look. And when Barry makes a train in clay every little rivet is visible. It’s made like a railway enthusiast would make a train and it’s a most wonderful colour… craft-wise it’s beautifully made, food for the eye.

Rex raku firing at Selwyn c 1974–5. Photographer unknown, Rex Valentine collection.

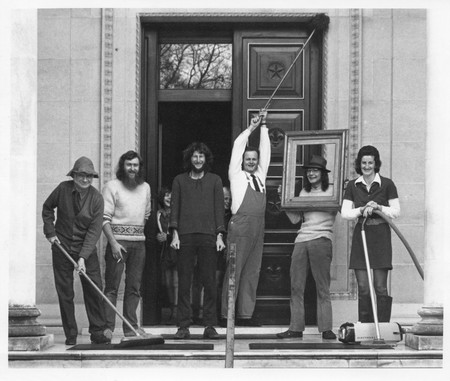

From left: Tom Gordon, Rex Valentine, Peter Lusk, Brian Muir, Michael Hamblett and Annella MacDougall on the steps of Robert McDougall Art Gallery in around 1973. Rex Valentine collection. Photo: Peter Lusk

GB: Can you tell me about the time you spent in Japan in the late 1970s?

RV: Zenji Uragami was invited to Christchurch in 1973 through the sister-city connection, and he exhibited in Ballantynes. He wanted to meet local potters, so Canterbury Potters had a lunch out at Roger Chaplain’s place at Coalgate. Before he left, he invited me out for dinner and asked if I’d like to go and work with him in Japan. I said yes, that would be amazing. Sir Hamish Hay, then mayor, encouraged me to apply for a Kurashiki sister-city travel grant, even though in theory Uragami was in Okayama-ken in Bizen, and they did a deal with Air New Zealand. Well, going to Uragami first was good, because that set me up in an apprentice studio. I stayed there for six months during which time we did three firings. Those firings were tremendous. They were done in those big climbing Anagama kilns, which fired over five days and nights, and you were rostered on in shifts to man the kiln.

GB: It must have been exciting! What sort of pots did you make?

RV: It was! I left for Japan in late 1976 and was away for fourteen months in total. I worked on tea storage jars or little vases, bowls and things like that. I’d go walking in the mountains every morning and I’d go up to these old kiln sites and dig clay and bring it back down to the pottery – they really thought I was from another planet I think. I was going back in time and they were sort of ‘now’. I like to see what drives things. Everything is driven by outer experiences… Uragami couldn’t speak English but selected work of mine for exhibition back in Christchurch. After that six months in Bizen I went on to Kurashiki and worked with Haruki Okishio for the rest of my trip. I bought back Japanese mingei craft-ware [folk art] which was shown at the McDougall.

GB: What’s happed to the work you made there?

RV: The pieces I consider the best are in my collection still, but I used to take Bizen pots I didn’t need and swap them for old antique pots. I’m an unapologetic hoarder and trader [both laughing]. And while I was over there I got a really good collection of very early tea ceremony bowls which I’m passionate about – those tea bowls have driven my life since then… and they helped in my pottery life.

GB: What sort of pots did you make in Kurashiki?

RV: When I arrived, they put me straight to work as one of the pottery production workers. I had things I had to make, glazed domestic ware. We travelled extensively, went to lots of places and visited museums. We had time where we could make our own things and we were encouraged to do so, because Okishio said before I go we’re going to have an exhibition of all the apprentices’ work, and you’ll be able to sell it and keep all the money.

GB: At home you have a number of vases with one strong vertical indentation – what is this mark about?

RV: It’s a focus mark I think. It breaks the surface and shows the plasticity of clay. It was made with bamboo – that was another thing I learned from Uragami, how to make bamboo tools…

GB: In June 1973 you curated a show of pots by the world-renowned Japanese potter Shōji Hamada at the McDougall. How did this come about?

RV: I had run across Hamada’s works in various collections around Canterbury and knew what had happened when he visited in 1965. He brought a whole collection of his pots out which were shown at the museum. And they were all for sale. There was such demand for them that they had this lottery – you put your name in the hat for whatever pot you wanted. Some people put in for everything and some got two. So that distributed the pots out reasonably evenly and they went to a lot of private people. I’d seen one or two and I had an interest so I read up on him. I talked to Brian Muir and he asked if I’d like to curate an exhibition. When Hamada was here that was the early days of pottery, and since he’d left a lot of people had become interested. The number of potters in Canterbury had trebled. So I got to go around all these collections and found out where his pots were. It took quite a bit of sleuthing, and then I travelled around and picked all these pieces up and we set up an exhibition in the McDougall. Michael Hamblett worked on the letterpress catalogue.

GB: You have a great photograph taken at the time on the McDougall steps; there is director Brian Muir with a feather duster, the custodian, Michael Hamblett and Annella MacDougall, the director’s secretary, with a classic Electrolux.

RV: Brian Muir created a great atmosphere amongst the staff and in that photo we were having a bit of fun – look at him with the feather duster! And note the kids peeking from inside.

GB: It’s clear to see that the passion to produce pottery was growing quickly during the 1970s. They could do it for a period of time, but things changed, didn’t they, due to cheap imported china and suddenly there was a shift away from the handmade.

RV: Yes. It’s a natural attrition. Something new starts and then it drifts off… My pottery career was quite short, it was maybe twenty years or something like that, which isn’t a long time. But I’ve never lost my love for pottery, it’s always stayed there. And through that time, I’ve always bought pottery and been interested in pottery, gone to exhibitions and educated myself.