Wayne Youle Lovers 2014. Silk screen. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2015

Wayne Youle: Look Mum No Hands

He’s been called a cultural prankster, an agent provocateur and a bullshit artist (that last description came from his dad, but it was bestowed – he’s pretty sure – with love). While we’re at it, add ‘serial pun merchant’ to that list; in art, as in conversation, Wayne Youle can spot a good one-liner a mile off and has never knowingly left an entendre undoubled.

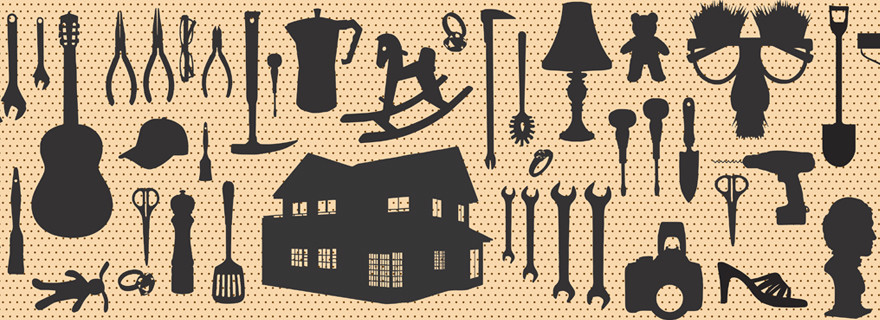

It’s fitting, then, that many of the qualities that have come to characterise his current art practice were not so much foreshadowed in his early work as sign-written. Under the guise of an optician’s eye chart, the gradually shrinking text of CULTURAL BLINDNESS TEST, exhibited as part of Youle’s 1999 Wellington Polytechnic Bachelor of Design graduate exhibition, wryly challenged his audience’s world views along with their vision. Deploying Youle’s now-customary blend of humour and provocation, it considered how we see ourselves and are seen by others, a subject with particular resonance for Youle. Of Ngāti Whakaeke, Ngāpuhi and European descent, he grew up identifying as Māori through his mother’s side of the family, but more closely resembling his father’s Scottish ancestors (his cross-cultural conception was memorably re-enacted by two entangled plastic dolls in the 2002 photograph And then there was Wayne…). He’s more alert than many to the categorisations and limitations that are consciously and unconsciously assigned to us, often without our consent or even our knowledge. Although at first glance CULTURAL BLINDNESS TEST suggested a uniform standard of measurement, the ‘dotting’ of the sans serif ‘I’ with a small plastic tiki, painted white, suggested something both more nuanced and more personal. Crisply rendered with sign-writer’s vinyl on canvas, it was an arresting demonstration of Youle’s ability to complicate an apparently simple visual premise with a lingering, ambiguous aftertaste.

A few years later, that facility was again at the fore in Often Liked, Occasionally Beaten (2003), a set of brightly coloured tiki, cast in resin and presented on white sticks as a row of dangerously alluring lollipops. This highly charged combination questioned the unthinking consumption and commodification of Māori culture, as well as the appetite for indigenous culture-lite; sweetened and simplified for a general palate. Youle’s Pop-ish tiki were laced with irony; he was well aware that even as he critiqued such practices, he too was creating questionable, but highly desirable, commercial objects.

Youle took up his artistic career only after finishing his design degree because his family initially considered art a bit flaky, and wanted him to train in something with more secure prospects. His early works often suggest an awareness of that ambivalence, and a residual uncertainty about his place in the art world – an anxiety often expressed with compensatory braggadocio. In a 2005 exhibition, Youle ostentatiously arranged twenty of his art ancestors around him as a series of nickel-plated silhouettes in the sardonically-titled Old Boy’s Club, playfully tweaking their most iconic works to open them up to a range of new interpretations. Colin McCahon’s thundering I AM made an appearance, as did Shane Cotton’s birds and the koru of Gordon Walters, the last coiled into swastika shapes to critique the artist’s appropriation of Māori artforms. With what Grant Smithies has called ‘a mix of cheek and longing,’1 Youle positioned himself in twenty-first place.

Wayne Youle ALONE TIME (detail) 2014. Mixed media. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2014

The question of how cultural groups perceive and label each other has remained a key concern for Youle, and fatherhood has provided him with an additional lens on the subject: ‘I know from my own children that racism and bigotry are taught. It’s irrelevant to them, and that’s how it should be.’2 From 12 Shades of Bullshit (2003), which featured aluminium cuts outs in the shape of historic images of Māori by European artists, each painted a slightly different colour (Too brown? Not brown enough?) to the gleefully cringe-inducing When I grow up I want to be Black (2006), a photograph of the artist in full minstrel blackface, skin colour has been a recurrent motif. Recently, Youle took the theme to its logical conclusion, purchasing a pound (just under half a kilogram) of ‘flesh-coloured’ paint – it was a shade of pink, naturally – from his local art supply store and applying it to a small, square canvas. The irony underscored by Youle’s work was that not only does this supposedly standard tone not represent the skin colour of much of the world’s population, it doesn’t resemble any skin you’re ever likely to see. Instead, it’s an unsettling and slightly gross approximation, in the same vein as the ersatz ‘selves’ of sculptor Ronnie van Hout. Titled .454 kg of whatever and who really cares, it is Youle’s reminder of the inadequacy of empirical standards in reflecting our multi-faceted reality, and the absurdity of measuring ourselves and others against them.

Wayne Youle Paper bags (detail) 2009. C-type photograph of hand-cut, screenprinted paper bags. Collection of the artist

Youle’s works exude a brash physicality, full of balls and nuts, bared bums, bones and fingers (sometimes crossed, sometimes flipping the bird). Occasionally, however, this focus on the body, and its potential to transform the world around it, takes on a (slightly) more existential note. In BEFORE/AFTER (2015), two objects cast in bronze occupy the same plinth. One is a scale replica of a shiny red gumball, the other a chewed one, masticated into unrecognisable ruin. It’s a testimony to the skill with which Youle creates his works, and the deadpan gravity with which he presents them, that these banal objects assume a temporary profundity; prompting, if he’s lucky, some gentle musing on life, death, aging and even the effect of humans on the earth itself.

In recent years, a heightened awareness of time (passing/spent/wasted/lost) has emerged as an important motif in Youle’s practice, reflecting his experiences as both the father to three young boys and the adult son of ageing parents: ‘The trigger was seeing my old man slow down. Then, with my children, it’s like the opposite; there’s no concept of time. You get home from the studio and its three hours on the ground playing Lego.’3 One work, March of the Good Bastard (2015) documented Youle’s father, Andy, walking one kilometre up his gravel driveway. Clad in a grey tracksuit, he trudges indomitably forward, tracing a slow trajectory across a vast backdrop of hills and sky, his steady progress marked by the power poles and fence posts he passes. It’s a surprisingly moving scene; a reminder of how an apparently standard distance is relative to the strength of our body, but also of how personal relationships are measured out in ordinary moments, rather than grand occasions. Because, of course, the solitary man on our screen is not really alone; his son walks beside him as a witness and participant. The titles of two later photographs derived from these videos – From whence ethic comes (walking out) and The place that honesty and determination lives (walking in) – revealed the sense of connection and appreciation Youle sought to capture. In 2015, the title he chose for his 9:54 / 3:49 exhibition at Sydney’s Carriageworks gallery further emphasised how distances seem to expand and contract in relation to our age by contrasting the time his father took to complete a kilometre with how long it took his five year old son Ārai to cover the same distance on his BMX bike.

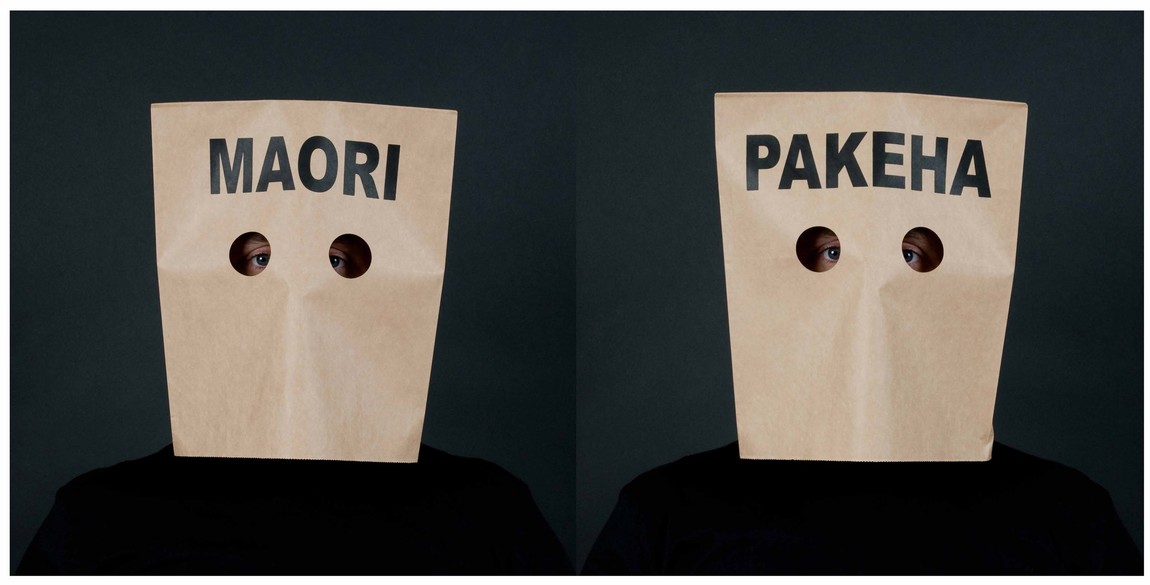

Wayne Youle That’s 2 hours, 1 minute and 40 seconds I am happy to give you 2014–15. Digital print on 308gsm Hahnemühle hot-press paper. Collection of the artist

For How long a piece of string actually is (2015), Youle asked his mother Jacqui to knit for him for a year. He didn’t dictate the outcome, just supplied her with a ball of bright orange acrylic wool and told her to ask him for more when she needed it. The ritual prompted new opportunities for contact between mother and son; she would ring him with updates, apologising for her lack of progress, he would reassure her that he had no expectations. At twenty-eight metres long, the completed work offers an intimate, alternative timeline – an organic document of time spent and given, and material evidence of the affection between parent and child.

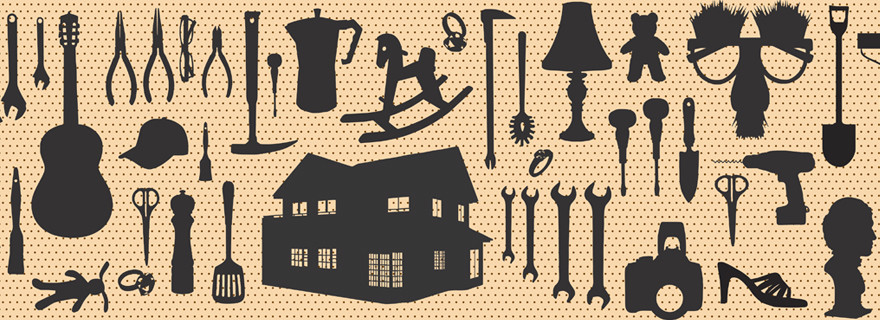

I’ve always found it telling that Youle’s massive post-quake mural in Sydenham, I seem to have temporarily misplaced my sense of humour (2011), arguably one of his most public works, took on a form that recalled a very private kind of sanctuary – albeit on a grand scale. Black silhouettes and regularly spaced perforations readily evoked the shadow boards that are a staple of the traditional Kiwi toolshed, where there’s a place for everything and everything is in its place. By augmenting the customary hammers and wrenches with less expected items – a guitar, a house, a rocking horse, a child – Youle drew a line between the disordering of familiar objects and routines following the earthquakes and the city-wide loss and dislocation that would be much harder to put right. The scale of that wall full of shadows matched the vastness of the challenge and Youle’s work struck a chord with a wide audience. Several people told me it was the first piece of art they ever really liked. His choice of imagery also tapped into a theme that runs through many recent works: the time and space he – and any artist – must carve out from the demands of everyday life. In ALONE TIME (2014), exhibited in Christchurch Art Gallery’s reopening exhibition, this physical and psychological ‘room of one’s own’ took the form of a 3.2 x 3.6 metre plywood bunker, which housed a wittily choreographed replica of the artist’s obsessively ordered, yet generously abundant, studio in Amberley. Amongst the works inside were many references to the self-doubt and work ethic that accompany and sustain the creative process – like the ‘thinking chair’ with a circle worn through the painted seat by the artist who always turns up.

There’s an interesting contrast between the ironic, self-deprecating humour that buoys Youle’s work – dryly undercutting the persona of the cocky creative genius before anyone can do it for him – and the discipline with which he carries out his practice. He’d be horrified if anyone thought he was taking himself too seriously, but he approaches the practical business of making art with conscientiousness and a hurricane-force intensity. Fatherhood has shunted his 9-to-5 work day to a 7-to-3 one, and he tries not to work weekends any more, but the ritual of those hours of graft in the studio remains a pillar of his practice – and he still vacuums at the end of each day. The ideas that spring up prolifically from his research – undertaken, as likely as not, on YouTube or in his local second-hand shop – are thoroughly proofed before they get anywhere near the public. Making is a fundamental part of his thinking process (a legacy of his design background), so almost every concept finds physical form, but only a tiny proportion will ever make it into a gallery. Over the years, he’s embraced a wide range of media, from sculptures and found-object assemblages to paintings, printmaking, video and ceramics; all rendered with exquisite care and united by a Prada showroom-level finish that encourages us to take a longer, closer look. Cracking his knuckles and limbering up his funny bone, he’s as obsessively well-prepared as any seasoned stage performer, even – especially – when it looks like he’s just winging it.