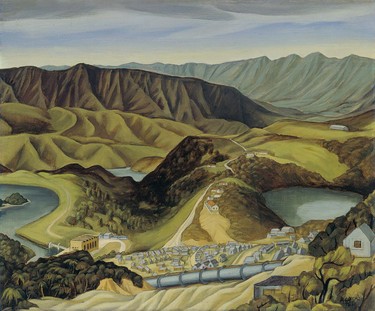

Doris Lusk Landscape, Overlooking Kaitawa, Waikaremoana 1948. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1955

Doris Lusk: An Inventive Eye

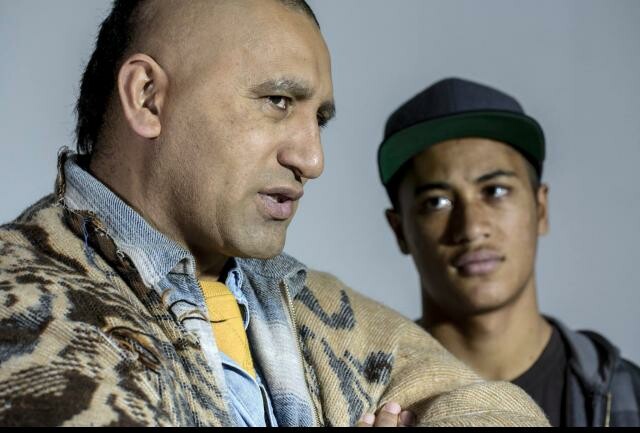

In the strange, stunned afterlife that ticked slowly by in the first few years following Christchurch’s February 2011 earthquake, a curious note of recognition sounded through the shock and loss. As a massive programme of demolitions relentlessly hollowed out the city, many buildings were incompletely removed and lingered on for months as melancholy remains – stumps abandoned in a forlorn urban forest. Hideous, sculptural, beautiful; they bore compelling resemblance to a body of paintings created in the city more than three decades earlier.

'Have you seen the new Doris Lusk on Armagh Street?’ some of us asked each other. Our forays into the decimated city brought to mind Lusk’s Demolition series, made between 1979 and 1982 in response to an earlier wave of destruction, when old buildings – including heritage structures – were razed to make room for modern office blocks and apartments. The paintings mark one of several high points in a career defined by invention and exploration, and their unnerving visual precognition is reason enough to revisit an artist whose work is as underrated as it is interesting.

Born in Dunedin in 1916, Lusk’s early artistic inclinations were encouraged by her architect father. His work took the family to Hamilton, where they lived in a house near the Waikato River, with Lusk enjoying occasional visits to the nearby studio of a local female artist. They returned to Dunedin in 1928, where Lusk attended primary and secondary school, infuriating her parents by leaving Otago Girls’ High School before her matriculation exam in order to enrol in the Dunedin School of Art at King Edward Technical College. The five-year course did not offer a diploma, but Lusk received a valuable education nevertheless. Through R.N. Field, she was exposed to progressive developments in European and British art (including the work of Picasso, Cézanne and expatriate New Zealander Frances Hodgkins) and learned how to model clay – in addition to her painting career, Lusk was a gifted potter, who later taught hundreds of pupils at Christchurch’s Risingholme Community Centre. Charlton Edgar provided technical advice on all aspects of the painting process and also encouraged his students to paint outdoors, direct from nature, introducing Lusk to the demanding Central Otago landscape. She attended Friday night life-drawing classes, and the occasional party, at the studio of Russell Clark.

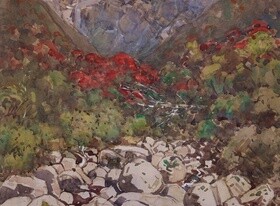

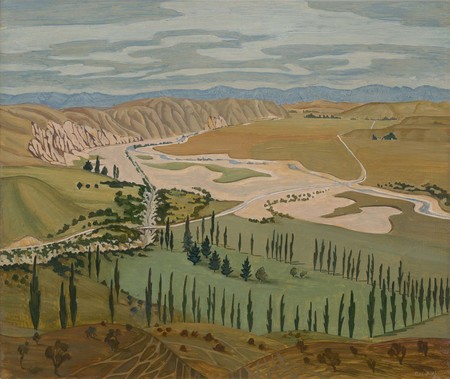

Doris Lusk Towards Omakau 1942. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, William A. Sutton bequest 2000

Lusk made friendships amongst her fellow art students and undertook painting expeditions with them throughout Central Otago and around Nelson. Some connections – such as that shared with Anne Hamblett and Colin McCahon – proved lifelong and artistically productive. McCahon and Lusk sometimes painted together, and a comparison of the works they made in response to similar landscapes reveals both a shared interest in the structure of the land and distinctly different motivations. Tackling a valley scene at Pangatotara (near Motueka) on one expedition together in the summer of 1942/3, McCahon cropped and condensed the view to reveal an imposing, monumental landscape, empty of human presence except for an abstracted building in the foreground.1 Lusk’s eye, in contrast, was drawn to the complexity of the scene; the sharply angled rows of the tobacco fields, the hop houses, trees and river beyond.2 Aside from their location, the one feature common to the two paintings was the inclusion of stylised, folded mountain forms; a motif that would become characteristic in both artists’ work. In McCahon’s painting they dominate the picture plane, lending it a timeless grandeur; in Lusk’s they are the final structural element that locks her intricate, tightly balanced composition into place. Both artists were moving steadily away from the established formulas of landscape painting, manipulating content, perspective and colour to suit their own purposes, but it was already clear they were heading in very different directions.

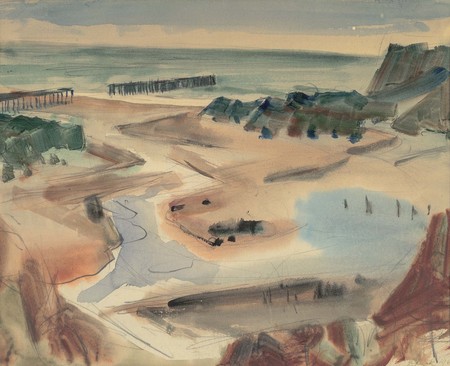

Doris Lusk Onekaka Estuary 1966. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Lawrence Baigent/Robert Erwin bequest 2003. Reproduced with permission

When Lusk married Dermot Holland in late December 1942 and moved to Christchurch, she knew few people there. However, she was fortunate to meet the painter and potter Margaret Frankel, one of the key figures in The Group, an alliance of independently-minded artists who rejected the conservative policies of the Canterbury Society of Arts.3 As Lusk later recalled ‘She made me a member almost at once, which was a really big deal, and I joined the arts society – and as soon as I could get a painting done I was getting into the arts life of Christchurch.’ One of the few female artists at that time to sustain a career while raising a family, Lusk fitted her artmaking around domestic life, using outings and holidays as opportunities for painting. Her daughter, Jancis Meharry, remembers family walks up to the Sign of the Bellbird on the Port Hills during which her mother, ‘who always carried a roll of pencils and a sketchbook’,4 would send the children off on a hunt ‘for a cowpat to put under the primroses’ while she drew the landscape. At home, Lusk set up her easel inside the playpen while the children played outside it: ‘she always had something propped up on the dining table, next to the bottling.’5 The Group provided both artistic stimulation and a schedule of combined exhibitions that suited her necessarily reduced output better than a solo exhibition: ‘I did not paint in a continual professional manner. I painted when I could, and I would produce about six paintings a year, which was pretty good going in the circumstances.’6

One of those works was Towards Omakau, a taut, yet exhilaratingly expansive view of a landscape near Alexandra, in Central Otago. Painted in 1942, it was owned by artist Bill Sutton and came to the Gallery upon his death in 2000. What a painting it is. With a sharply elevated perspective, the view falls rapidly away, rolling back across the plains to the hills and mountains beyond. Perhaps most striking are the numerous lines that stretch over its surface; curving round the plaited hills and eroded gullies, extending in darting tangents as rivers and roads, forming regimented shelterbelt verticals. Sheep trails crisscross gently rounded hills, echoing the enigmatic swirling patterns of the clouds overhead. It’s undeniably modern – a far cry from the sublime or topographical archetypes that once dominated depictions of the New Zealand landscape – and although its rural subject might lead some to brand it as simple, straightforward regionalism, you soon see how carefully Lusk has stripped back and orchestrated the original view. As she revealed in a 1987 Kaleidoscope interview: ‘I don’t think that I ever approached landscape from just a sort of total realism. [It] had to be controlled and restricted, composed into pictorial space.’7 Lusk readily altered what she encountered, but, unlike McCahon, didn’t empty out her landscapes to increase their impact, instead focusing on the structures that bound them, invisibly, together. Reflecting on her work in later years, she stated: ‘[I] have tried to get to the heart of the matter, involved with the complexity rather than simplicity in describing the nature of our land.’8

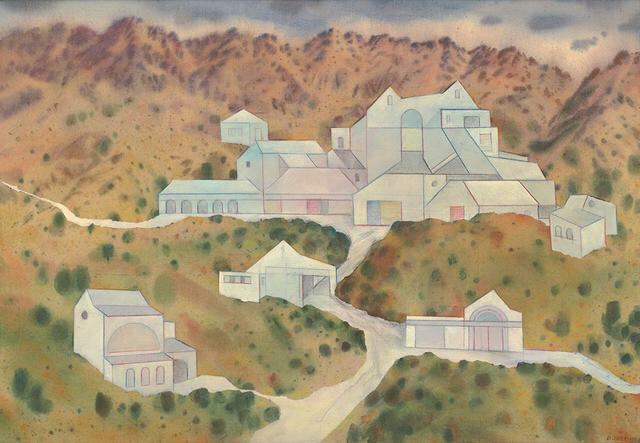

Lusk’s eyes were always keenly attuned to structure. As Anne Hamblett recalled of their art school days: ‘Doris always did a different sort of thing. Buildings and water stations. […] She liked doing big water pipes and machines.’9 Another work in the Gallery’s collection, Landscape, Overlooking Kaitawa, Waikaremoana (1948) records Lusk’s fascination with a newly built hydroelectric complex she visited while staying with close friends Adelaide and Ian McCubbin (Ian was a construction engineer on the project). Even now, it’s a strangely mutable work, as the pipeline in the foreground seems to continually shift in scale; looming hugely over the construction workers’ miniature houses, but then dwarfed by the mountain ranges that tower in the distance.

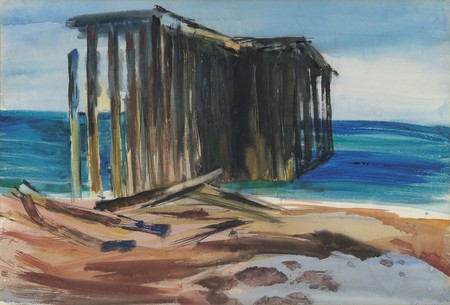

Doris Lusk Acropolis, Onekaka (The wharf) 1966. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Lawrence Baigent/Robert Erwin bequest 2003. Reproduced with permission

Lusk’s friendship with the McCubbins eventually led to her discovery of a subject that would captivate her for more than twenty-five years. Built in the 1920s to load pig iron from the nearby ironworks, the Onekaka wharf in Golden Bay had fallen into disrepair long before Lusk first saw it in 1965. By then, it was no longer connected to the sea (it has continued to decay and is now little more than a grouping of black posts), and she found its dramatic break at the low tide mark irresistible. Years later, she recalled how she had set out that first day, determined not to paint it, only to return with a sketchbook full of little else. For the next five years, she would paint it almost exclusively, fascinated by the interplay between light and shadow, structure and fluidity, strength and decay. Lusk’s developing interest in watercolour gave her the tools she needed to capture the estuary’s luminous light and changing tides. Justifiably proud of her ability to adapt to, and master, new techniques and materials, she enjoyed the challenges posed by this unstable medium, soon learning to exploit a combination of fluid washes, calligraphic slashes and frothy splashes to convey the unique and complex environment of the wharf. At this key moment in her creative development, Lusk was appointed to the position of drawing lecturer at the University of Canterbury, a role she held for more than fifteen years. She found the environment stimulating and the stability it provided allowed her to expand her practice further, working her way through an expanding range of techniques and subject matter.

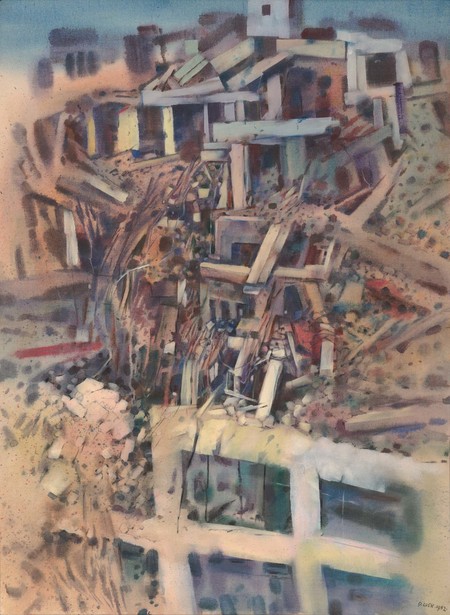

Doris Lusk Finale 1982. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1982

One afternoon in 1979, two years before her retirement from the art school, Lusk chanced upon the sight of a half-demolished building. It was, she recalled later, a moment of revelation. She immediately realised the possibilities of ‘that extraordinary drama of texture and lighting…’10 Looking at what now appear as oddly prescient views of demolitions on Tuam Street and in the Arts Centre complex, it is easy to see why these broken structures, with their tangled spatial ambiguities, varied textures and complex lighting, challenged and captivated Lusk. Collaging together her own photographs and those clipped from newspapers to create imaginary compositions, she then translated these into an expressive mix of watercolour, acrylic and coloured pencil. Throughout her career, Lusk had firmly resisted attempts to assign psychological motivations to her paintings (her ‘desolate’, ‘claustrophobic’ compositions, those ‘disturbing’ juxtapositions between the natural and industrial worlds). Accordingly, she gave short shrift to any who saw in her Demolitions an elegiac commentary on the human condition: My work is really very practical, and it would be quite dishonest if I tried to put in psychological meanings […] The Demolition works were a little misunderstood. [People thought] that I became very fascinated with the factual destruction of buildings as a sort of sociological thing. But that was not true […] It was a visual image to hang my media painting on, that’s all.11

In a typically deft summation of this artist who combined practicality with acute investigation, her friend and teaching colleague Don Peebles wrote of Lusk after her death: ‘She had little patience for posturing, but observed the world with a penetrating eye and set about the exacting process of bringing it to account in her painting.’12

Doris Lusk: Practical Visionary, an exhibition marking the centenary of the artist’s birth, will be on display at the Gallery from 4 June until 30 October 2016.