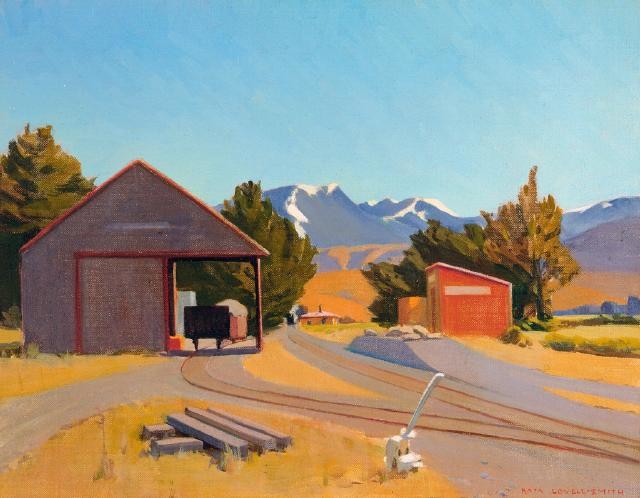

Margaret Stoddart Camping at Akaroa 1893. Album 2, Canterbury Museum, 2015.115.46-50, p.12

Exquisite Treasure Revealed

Anthony Wright and Julie King shed light on a collection of drawings and photographs compiled by artist Margaret Stoddart.

Canterbury Museum holds two albums compiled by Diamond Harbour artist Margaret Stoddart. The older of the two, containing images featured in this Bulletin, and itself currently exhibited in the Gallery, covers the period 1886–96. The album is handsomely bound in maroon, and stamped M.O.S. in gold. It contains a sort of travelogue by way of black and white photographs set amongst decorative painting, mostly of native flora, with some locality and date information.

It records her visits to the Chatham Islands, various places around Canterbury and the Southern Alps, and abroad in Tasmania and Victoria, Australia. I wish we could tell you more about how and when the album came to the Museum; the report recommending its formal accessioning in preparation for the loan to the Gallery simply notes that it has ‘unknown provenance’.

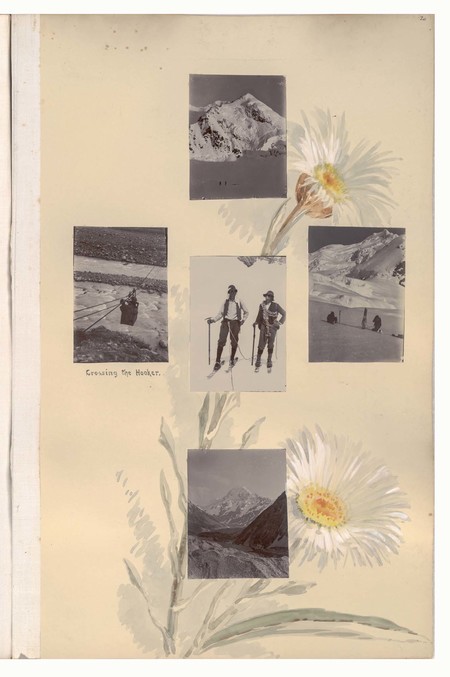

As a botanist by training (and at heart), I find the plant portraits are both pleasing in composition and botanically accurate enough to allow identification. Crossing the Hooker is embellished with two heads of the large mountain daisy Celmisia semicordata. Over the page, a photograph of a large clump of Mount Cook lilies (actually a buttercup—Ranunculus lyallii) lies over an exquisitely painted scape of its flowers which seems to leap from the page.

Museums and galleries care for a myriad of hidden treasures behind those on public display. It’s great that the reopening of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū can also shed light on some of Canterbury Museum’s unseen taonga.

Anthony Wright

Director, Canterbury Museum. Credits written by Julie King, art historian and author of Flowers into Landscape: Margaret Stoddart

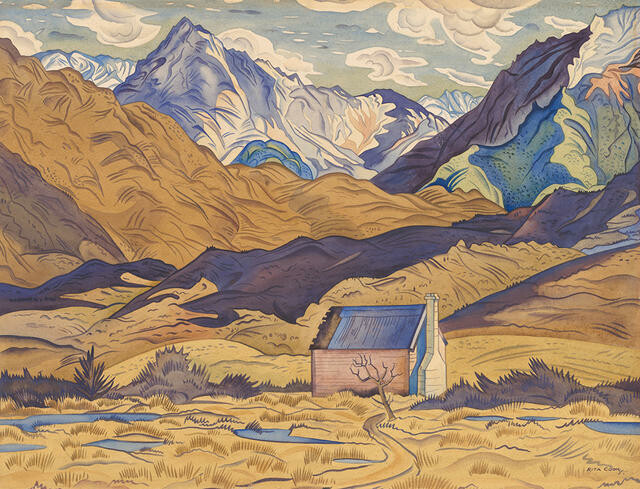

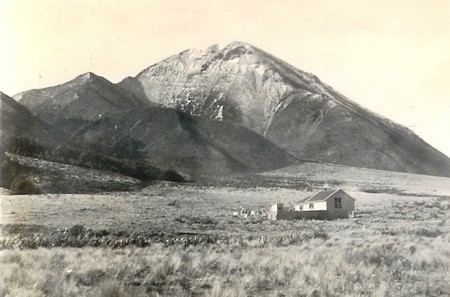

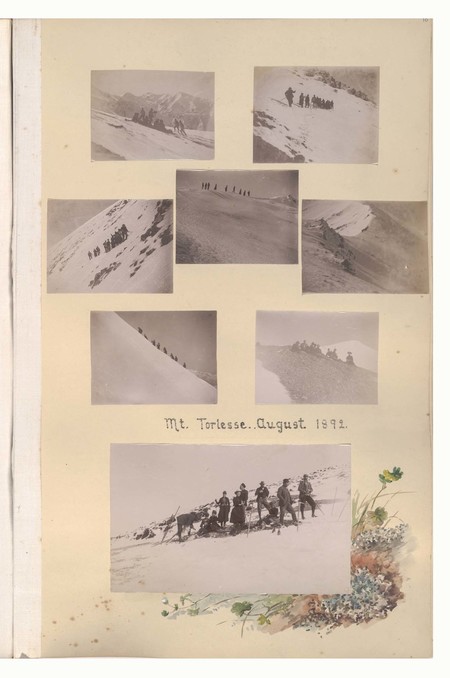

Margaret Stoddart Mt Torlesse 1892. Album 2, Canterbury Museum, 2015.115.34-42, p.10

Mt Torlesse 1892

In August 1892, Margaret joined a climbing expedition to Mount Torlesse. These photographs, which were taken with a hand-held quarterplate camera, record the arduous ascent. The party spent seven hours travelling across snow and the frozen and slippery shingle to the steepest slopes, where they were roped together, and reached the summit by cutting steps into the ice. On 1 September, the Canterbury Times commented that ‘Christchurch ladies are now adding the invigorating pastime of mountaineering to their other athletic pursuits … and, are specially to be commended for the plucky way in which they took to it.’

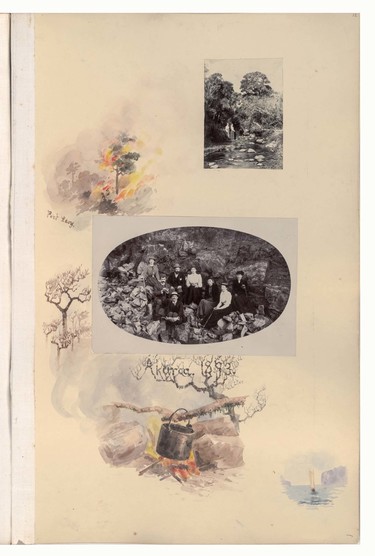

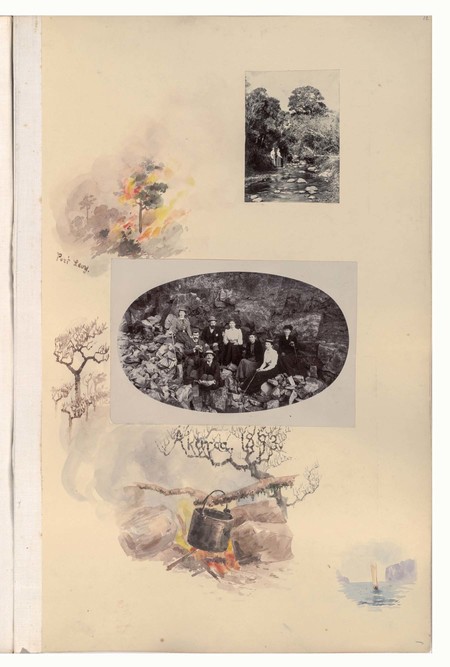

Margaret Stoddart Camping at Akaroa 1893. Album 2, Canterbury Museum, 2015.115.46-50, p.12

Camping at Akaroa 1893

Walking parties were popular in Margaret’s social circle, and the Port Hills and Banks Peninsula were favourite destinations. One clipping in her sister Mary’s album describes an excursion to Akaroa and back, which was completed in four days. Taking the launch to Diamond Harbour, the party walked to Purau, along the Port Levy road and on to Little River, with an overnight stay at the Hill Top, before making their descent into the harbour. Margaret can be identified in the photograph, wearing a white blouse, and seated at the centre of the group. Her lively sketches illustrate the excursion.

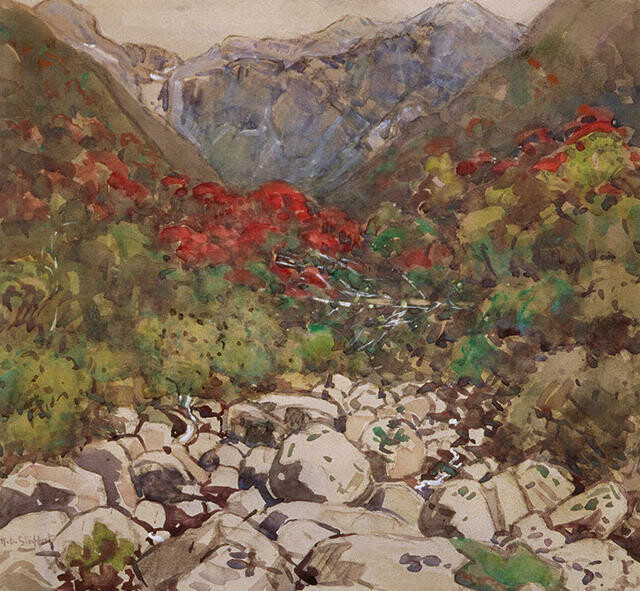

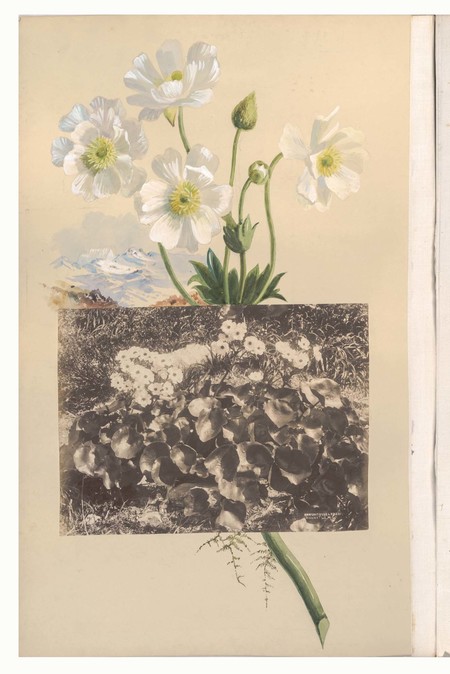

Margaret Stoddart Mount Cook Lilies. Album 2, Canterbury Museum, 2015.115.83-84, p.21

Mount Cook Lilies

On this page, Margaret placed a photograph of Mount Cook lilies, which is combined in a highly original way with her painting of the plant, and a background of snow-capped mountains. The flowers are captured in the clear light, and the delicate white petals shine from the page. When Margaret was a young woman, she completed numerous paintings of New Zealand’s native flora. Her personal album, which was made for the perusal of her family and friends at home, provides a fascinating glimpse of the artist’s adventurous travels, and an insight into her youthful aspirations.

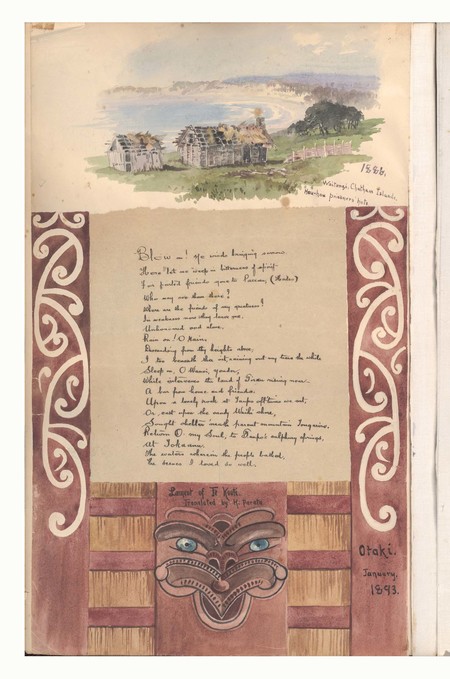

Margaret Stoddart The prisoners’ huts on Orea flat, overlooking Waitangi Bay, Chatham Islands, 1886 (above) with the Lament of Te Kooti, translated by H. Parata at Ōtaki, January 1893. Album 2, Canterbury Museum, 2015.115.3-4, p.1

The prisoners’ huts on Orea flat, overlooking Waitangi Bay, Chatham Islands, 1886 (above) with the Lament of Te Kooti, translated by H. Parata at Ōtaki, January 1893

On 19 April 1886, Margaret travelled to the Chatham Islands, where she stayed for over a year painting the landscape and indigenous flora. This drawing in her album depicts the huts on Orea flat overlooking Waitangi Bay, where the Māori leader and prophet Te Kooti had suffered unjust imprisonment and exile. In 1893, Margaret added a sheet inscribed with verses from the Lament of Te Kooti translated by H. Parata. These were framed within a painted border in the hammerhead shark design that could be seen on the kowhaiwhai panels of Rangiātea, the great Māori church built at Ōtaki.

Margaret Stoddart Crossing the Hooker. Album 2, Canterbury Museum, 2015.115.77-82, p.20

Crossing the Hooker

These photographs come from the attempted ascent of Mount Cook, made in November 1893 by celebrated mountaineers Marmaduke Dixon, George Mannering and Tom Fyfe. This was the first expedition to use skis as a means of combatting the snow-covered crevasses. The skis had been ingeniously constructed from the blades of a harvester by Dixon, the brother of Rosa Dixon (later Spencer Bower), and a close companion of Margaret around this time. He is standing in the foreground of the photograph in the centre, which is crowned with a painting of the mountain daisy, a plant that flowers in spring and early summer.