B.

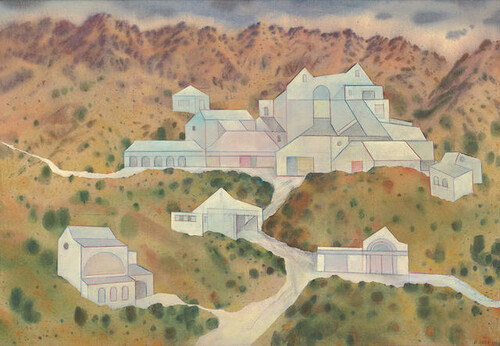

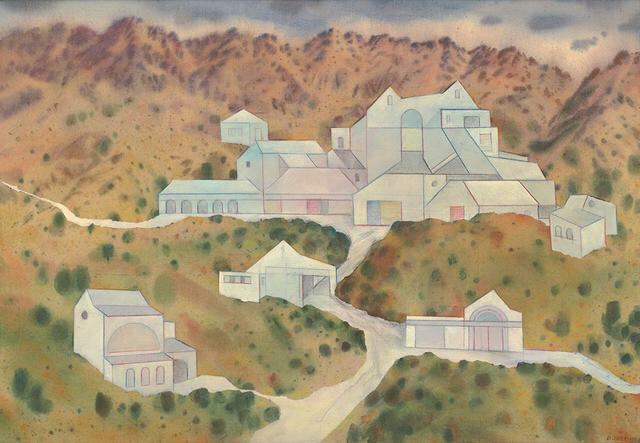

Imagined Projects II, Limeworks by Doris Lusk

Collection

This article first appeared as 'Work evolved from years of practise' [sic] in The Press on 3 November 2016.

When Doris Lusk (1916–1990) gave up her position as senior lecturer at the University of Canterbury’s School of Fine Arts in 1981, some – perhaps those who didn’t know her very well – might have expected her to ease her way into a comfortable, well-earned retirement. She certainly felt the weight of that expectation and, in interviews conducted at the time, made a point of stating her position clearly. Lusk wasn’t slowing down; in fact, this was a moment she had been waiting for all her life. After years of fitting her painting around raising her family and working life, she had a studio of her own (the realisation of a childhood dream) and she wasn’t about to let it go to waste. Instead, her academic retirement would lead to the rebirth of her painting; allowing time, in her words, “to think of the potentials of the next stage of my life”.

R.N. Field, Lusk’s tutor at Dunedin’s King Edward Technical College, had encouraged her to follow the example of Cézanne by representing, rather than merely replicating, what she saw. Over the years, she increasingly manipulated her subject matter to reflect her creative agenda, and by the early 1980s was regularly using her own photographs as a source, cutting them up and rearranging them with other found imagery such as news clippings into collage form before reclaiming them in paint. Lusk’s last major series, Imagined Projects and Imagined Views, was the culmination of six decades of practice and thought. The six ‘views’ were landscapes undertaken in oil, painted from memory. The seven ‘projects’, however, took her long-held interest in architecture and built structure to a logical, but remarkable, conclusion. Juxtaposing invented backgrounds with oddly dislocated buildings, they were painted using a distinctive technique Lusk had perfected through trial and error. Starting with a wet canvas, she laid out an imaginary landscape in washes and flicks of acrylic. After letting it dry, she added a series of incongruous, propositional buildings in opaque white, delineating their cleanly masked edges and windows with coloured pencil. The contrast was both disconcerting and intriguing. As Lusk described it: “I found these opaque surfaces led to extraordinary alterations of dimensions. They would put things forward and put things back in the most fascinating way.”

Lusk based the buildings in this work (on display at Christchurch Art Gallery as part of Doris Lusk: Practical Visionary until 31 October) on images of the Takaka limeworks, but their final, reduced form undermines any conclusive sense of purpose. Such ambiguity extends to every aspect of the painting, which is a carefully resolved study of contrasts: between light and dark, presence and absence, precision and expression, reality and imagination. Everything hinges on the relationship between the building and the land, which seems to alter moment by moment. As painter and friend Bill Sutton recalled, “It was hard to say whether the buildings were imposed on the hillside or the hillside encroached on the buildings because the areas were so beautifully interlocked; they were of equal importance. That struck me as being a wonderful solution to what I’d been after for a long time. A totally evolved painting.”