Trove

Recounting the untold stories behind some of the works in the exhibition Treasury: A Generous Legacy, curator Ken Hall also underlines the value of art philanthropy.

Investigating the stories behind the many gifts and bequests in Treasury has been satisfying in many ways. For a start, the research process nicely feeds the detective instinct; for this project it has been a collaborative activity, with dues rightly paid to colleagues Tim Jones and Deborah Hyde. Piecing together elements from sources including artist and object files, books, wills, archives and historical newspapers online (from France, Britain, Australia and New Zealand) also helps us see how our collection has come together. The understandings gained can tell us much about our shared past and the multiple facets shaping Christchurch culture. With this, our research has highlighted the inspired efforts and generosity that have supplied strength to our historical collection, uncovering many fascinating, often hidden, histories connected to works of art. The stories told here contain links to some of art history’s most famous names; extraordinary wealth connected to colonial roots; banished occupants of a royal palace; a young woman's likeness with an excess of admirers; and a significant Tainui leader and his European contacts. Some of these paintings had been enjoyed by the privileged few before entering this collection; others briefly shared with a larger crowd. All are loved works within this collection, including two relatively new arrivals, and all have benefited from this intensified recent research.

The Physician 1653

Gerrit Dou

Gerrit Dou The Physician 1653. Oil on copper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Heathcote Helmore Bequest 1965

Gerrit Dou (1613–1675), a leading figure in Dutch painting’s Golden Age, became Rembrandt’s first pupil aged just fourteen, studying under him for three years from 1628; before long he had eclipsed his master’s reputation and his extraordinarily detailed paintings were being prized by wealthy collectors. Bearing Dou’s signature and the year 1653, The Physician is one of four near-identical versions—a copy at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is the only one not signed. The one believed to be the original, in Vienna, is painted on oak; the others are on copper. It was not exceptional for artists such as Dou to make copies of their own works in response to demand.

This painting’s earliest documented owner is the Somerset-born Henry Francis Gray (1837–1905), who reached Port Lyttelton in 1856, aged eighteen, to farm in Canterbury. His brothers Ernest and Albert also took this path. He and his seven siblings were already well-off in 1870 when their father, the Reverend Frederick William Gray of Castle Cary, died and left a fortune of £210,000 (having the buying power of $17,000,000 today) as well as an (undocumented) art collection.

In 1881, Henry Gray was commended in local newspapers for lending The Physician for the Canterbury Society of Arts’ first exhibition. He left New Zealand for South Africa and the Argentine in 1899, and the painting passed through family lines to his great-nephew Heathcote Helmore (1894–1965), a prominent Christchurch architect, who bequeathed this treasure to the Gallery in 1965.

Les Puritaines/La Lecture de la Bible 1857

Henriette Browne

Henriette Browne Les Puritaines/La Lecture de la Bible 1857. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by R.E. McDougall 1930

Henriette Browne (1829–1901) was a well-known French painter of religious and Orientalist themes; this painting has many interesting names attached to it.1 Evidently depicting young sixteenth-century Huguenots contemplating scripture, it was first exhibited at the 1857 Paris Salon as Les Puritaines.2 The author Jules Verne recorded Browne exhibiting ‘four excellent canvases’ in his review of the Salon, but sympathised less with the subjects of this work than the painter had: ‘Les Puritaines are painted with a conscientious truth; everything in their features, in the asceticism of their faces, in the cut of their grey garments, in their stiff and serious attitude, denotes very well the daughters of Protestantism’s most intolerant sect.’3

Painted during the early years of the Second French Empire (1852–70), at which time thousands of opponents of Emperor Napoléon III were being imprisoned or fleeing into exile, Les Puritaines—in picturing persecuted citizens of the past—may have permitted a gently political reading.4 Any such interpretation, however, did not hinder its purchase at the Salon by the Empress Eugénie. It was displayed until 1870 at the (soon to be destroyed) Tuileries Palace, when she and her husband went into permanent exile in England following his crushing defeat to Prussia. Napoléon died three years later; this and other paintings were restored to Eugénie in 1881.5 Following her death in 1920, it was sold in 1922 at Christie’s in London (renamed La Lecture de la Bible) to the Sydney art dealer William J. Wadham, who sold it to Christchurch art dealer John Walker Gibb. After being shown in Dunedin at the 1925–6 New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition, it was purchased by the Christchurch biscuit manufacturer Robert E. McDougall, donor of Christchurch’s first public gallery, and became a part of his extraordinary civic gift.

Teresina 1874

Frederic Leighton

Frederic Leighton Teresina 1874. Oil on canvas board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the Canterbury Society of Arts 1932

The name Teresina appears in a notebook list of models sketched by Frederic Leighton (1830–1896) in 1874 while in Rome, where he typically relocated from London each autumn. The completed painting, like other of his portrait studies from the late 1850s onwards, shows the influence of Renaissance portraiture, presenting his (often Italian) sitters in a restrained, simplified style. This was in contrast with his vast history paintings packed with human figures, including Daphnephoria, a five-and-a-quarter metre long work shown at the Royal Academy in London in 1876 alongside Teresina. Picturing an ancient Greek festival honouring Apollo, it captured all of the attention. But this little picture also sold.

Teresina had several owners, all serious art collectors, in the thirty years before coming to Christchurch. The first, Charles Peter Matthews, was a wealthy brewer with homes in Mayfair and Essex, who died in 1891. It was then purchased at auction by Aylesbury picture-dealer Robert Gibbs, who sold it to the Reigate-based John Rudolph Lorent, a former Rothschilds’ banker who spent all that he could on art. His need to raise a dowry for his daughter in 1894 coincides with his parting with Teresina. The next owner was Thomas Craig-Brown, a Scottish woollen manufacturer and antiquarian who was praised for lending it to the Scottish Royal Academy Exhibition in 1896. Inexplicably, he also allowed it to be sent to Christchurch for the 1906–7 New Zealand International Exhibition and purchased for £100 by the Canterbury Society of Arts. Teresina was presented to the city’s new Robert McDougall Art Gallery in 1932.

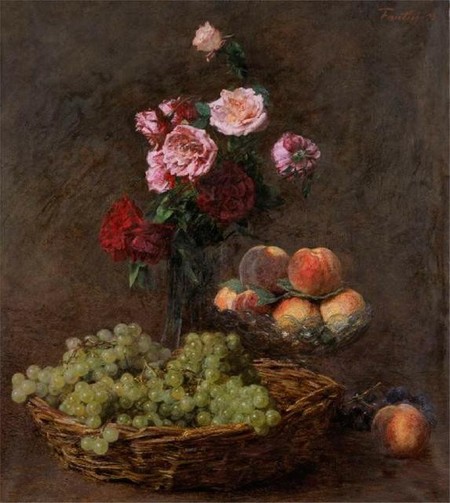

Panier de Raisins 1893

Henri Fantin-Latour

Henri Fantin-Latour Panier de Raisins 1893. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Frank White Bequest 2001

Every June from 1878 onwards, once the clamour of the Paris Salon had subsided, the painters Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904) and his wife Victoria (née Dubourg, 1840–1926) closed their Paris apartment and headed to the country, a small house with a garden in Lower Normandy, working there until the summer had ended. From Paris, Fantin-Latour shipped his most successful new fruit and flower paintings to his London friends, the art dealers Edwin and Ruth Edwards. Edwin Edwards had supported Fantin-Latour when Paris was in turmoil in 1871 at the close of the Franco-Prussian war by clearing his studio of drawings and still-life paintings to sell in England. Subsequent demand for his work from English collectors created a regular income for Fantin-Latour, whose still-life works were for a long while unknown to his countrymen. As the painter Jacques-Émile Blanche complained in 1919, ‘For too long, they were not found in France; Fantin was revealed to us only through rare portraits and fantasies.’6

Panier de Raisins (basket of grapes) was purchased through Ruth Edwards in London. Its buyer is unrecorded, but it was almost certainly purchased by the parents of its donor, Frank White (1910–2001), a Hororata sheep and cattle farmer and arborist who brought his mother’s belongings to New Zealand following her death in Somerset in 1935. White came to New Zealand in 1927 to study farming at Canterbury Agricultural College (now Lincoln University). Graduating in 1929, he served with the New Zealand armed forces in North Africa and the Mediterranean during the Second World War, and never married.7 Following his death in 2001, the Gallery was offered first choice of his paintings by bequest. Twelve were selected, among which this work is the most exceptional.

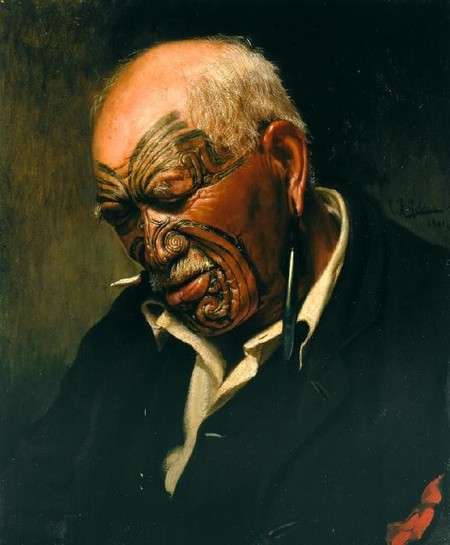

A Hot Day: Wiremu Pātara Te Tuhi, Ngāti Mahuta 1901

Charles Frederick Goldie

Charles Frederick Goldie A Hot Day: Wiremu Pātara Te Tuhi, Ngāti Mahuta 1901. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the Canterbury Society of Arts 1932

Wiremu Pātara Te Tuhi (1823?–1910) of Ngāti Mahuta was a well-known resident of Mangere, Auckland when his portrait was first painted by the thirty-year-old Charles Frederick Goldie (1870–1947) in 1901. Goldie had spent six years studying abroad from the age of twenty-two, mostly in Paris, returning in 1898 as ‘a young and promising artist’ with an impressive European art training behind him.8 By 1900, he was showing a mix of portraits of European and Māori sitters at the Auckland Society of Arts. He exhibited two portraits in the following year with the Canterbury Society of Arts.

Goldie and Pātara were introduced to each other in 1901 by the writer and historian James Cowan, who observed the first of their many collaborations and had also interviewed Pātara in depth. On 18 February 1902, his detailed biography of Pātara filled almost a page of the Christchurch Star. This may have been by design, as seven weeks later Goldie’s first two portraits of him, including this one, were shown at the Canterbury Society of Arts. Christchurch readers had opportunity, therefore, to become apprised of major aspects of the Tainui leader’s life, receiving at the same time a potted history of New Zealand, with the sorry truths of colonisation thoroughly embedded. Pātara was most animated when describing his involvement in the Māori King Movement, including as a newspaper publisher and as secretary to his cousin King Tāwhiao; their long exile in the Waikato ‘King Country’; and their visit to England in 1884 in the hope of proper recognition from Queen Victoria of the Treaty signed in 1840 on her behalf.9 A Hot Day was purchased in April 1902 by the Canterbury Society of Arts shortly after the exhibition opened, and presented to the city’s new gallery in 1932.10

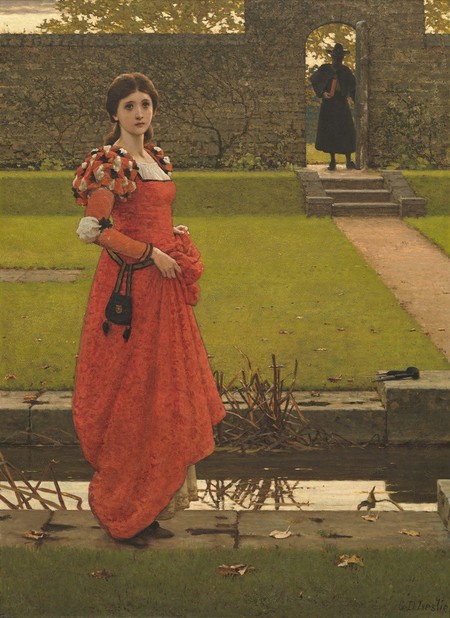

In the Wizard’s Garden c.1904

George Dunlop Leslie

George Dunlop Leslie In the Wizard’s Garden c.1904. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented to the Canterbury Society of Arts by W. Harris, 1907; given to the Gallery in 1932

George Dunlop Leslie (1835–1921) was a prolific, successful artist who exhibited annually at the Royal Academy in London from 1859—usually theatrical, symbolism-laden paintings of young women from a previous age. He exhibited In the Wizard’s Garden at the Academy in 1904. Both the artist and the painting’s donor, Wolf Harris (1833–1926), were present at the opening.11 Harris, a Kraków-born, London-based Jewish businessman with New Zealand connections, had already purchased a work by Leslie for himself, and was regarded as ‘a great friend of many of the artists […] accustomed every year just after the opening of the Academy to entertain at dinner the president and other academicians’, probably including Leslie.12 Harris (born Wolf Hersch Schlagit) moved to Australia from Poland in 1849, to Wellington in 1851, and then to Dunedin in 1857 during the Otago gold rushes, and there founded Bing, Harris & Co., a highly successful clothing importing and manufacturing company. Establishing branches throughout New Zealand, he opened another in London after moving there permanently in 1864.13 Harris maintained his New Zealand links and made business trips, the last in 1898. When George Leslie lent In the Wizard’s Garden for the 1906–7 Christchurch International Exhibition, it was Harris who purchased it for the Canterbury Society of Arts, who in turn gave it to the city in 1932.