Sir Henry Raeburn Brigadier-General Alexander Walker of Bowland (detail) 1819. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the Walker family 1984

The East India Company man: Brigadier-General Alexander Walker

Getting to know people can take time. While preparing for a future exhibition of early portraits from the collection, I'm becoming acquainted with Alexander Walker, and finding him a rewarding subject. Painted in 1819 by the leading Scottish portraitist of his day, Sir Henry Raeburn, Walker's portrait is wrought with Raeburn's characteristic blend of painterly vigour and attentive care and conveys the impression of a well-captured likeness.

Alexander Walker's steady gaze inhabits craggy, lived-in features. Although well accustomed to leadership, he wears a stoic humility; he appears thoughtful and humane. Indeed, he is a man who has weighed significant matters. Walker's far-reaching experiences and observations have also been preserved within his substantial body of writings, most of which are unpublished. Yet his remarkable story remains hardly told.

Walker was born in 1764 in Collessie, Scotland, the eldest of five children. His father William, a Church of Scotland minister, died when the boy was seven. Although he was able to study at the grammar school and university at St Andrews, he later recalled that 'poverty was vouchsafed... as a Counter balance to Family Pride [and its] younger Branches had to seek their fortunes in distant lands'.1

His transition to adulthood would occur in India.

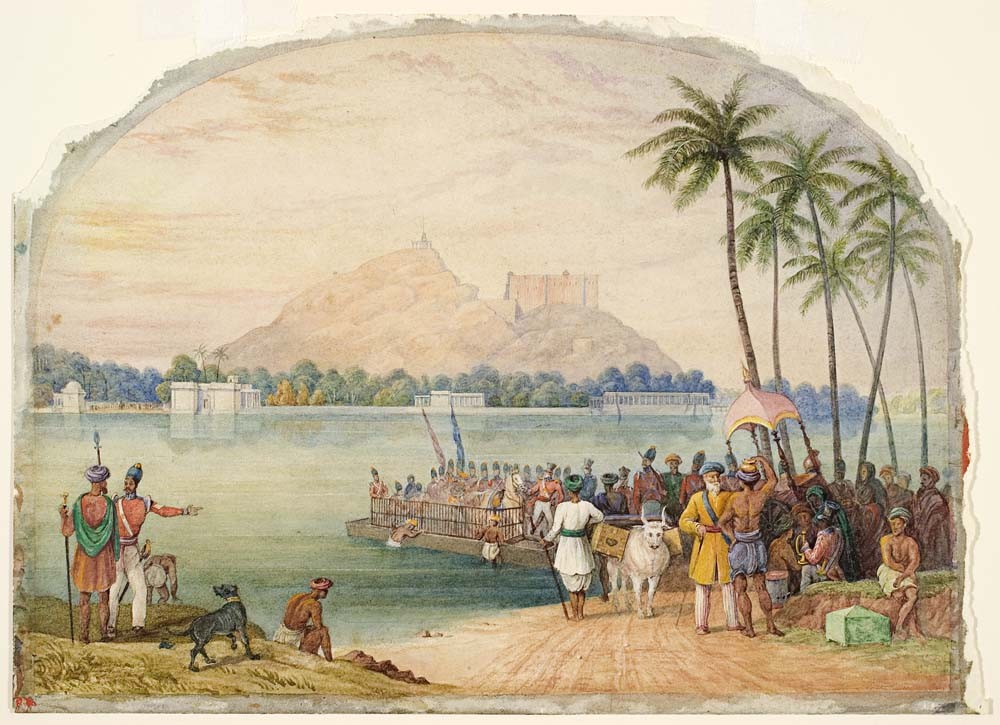

William Daniell Troops crossing a river in India c.1790. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

A cadet in the East India Company from 1780, Walker sailed to Bombay in 1781. The following year he became an ensign and took part in a campaign against the forts of the Muslim military ruler, Hyder Ali, on the Malabar Coast. He also fought with the 8th Battalion in defence of the fort at Mangalore against a siege led by Ali's son, Tipu Sultan. When the British surrendered on 30 January 1784, though severely wounded, he offered himself as one of two required hostages during a truce, 'notwithstanding the reputation of Tippoo at that period ... for cruelty and perfidy'. For four months they 'were subjected to a variety of privations and insults, and even considered their lives in danger'.2

Unknown artist Tipu Sultan undated. Ink, gouache and gold on paper. UC Berkeley, Berkeley Art Museum

The National Library of Scotland holds a vast archive of Walker's correspondence and papers, running to almost 600 large volumes, many of which he had prepared for publication. Among these is a hefty journal titled Voyage to America, 1785, which was finally published nearly 200 years after the event.3 Ensign Walker was barely twenty-one when he was chosen to accompany a private expedition to the north-west coast of America, 'the object [of which] was to collect furs and to establish a military post at Nootka Sound, which it was intended he should command'.4 Fur was required for the China market and in the hope of opening trade with Japan. Inspired and guided by an account of James Cook's third voyage, published in 1784, Walker and his companions spent most of their time at Friendly Village (Yuquot), a seasonal settlement in Nootka Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island, purchasing mainly sea otter pelts from the local population. 'Experience showed us,' Walker wrote, 'that the best method of Trading with these People was to wait patiently on board, where the Canoes never failed to flock from all quarters. We never had any success, when we pursued them ashore.' The most desired commodities for the Nootka were copper and iron.

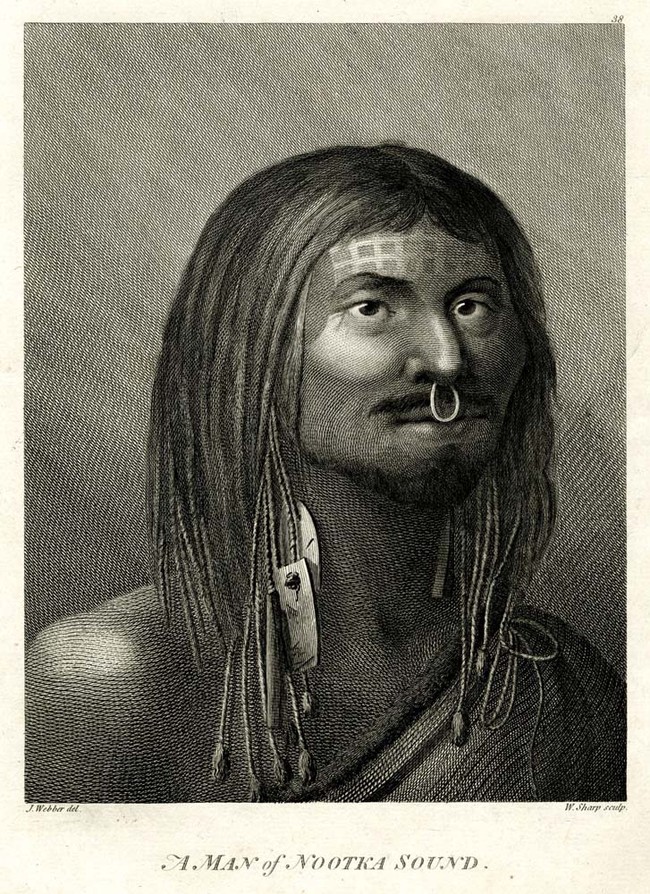

William Sharp, after John Webber A Man of Nootka Sound 1784. Engraving. British Museum

An illustration by John Webber, A Man of Nootka Sound, mirrors Walker's description of an individual who captured his attention upon their arrival:

A person in one of the largest Canoes, whom we supposed to be a chief, from the superior ferocity of his looks, and the exclusive privilege, that he seemed to enjoy, of sitting idle. He was about 35 Years old, and apparently possessed of much strength. He had his face eminently disfigured, and his Hair plaistered with red ochre, thick powdered with feathers, and tied in a bunch over his forehead with a Straw rope.5

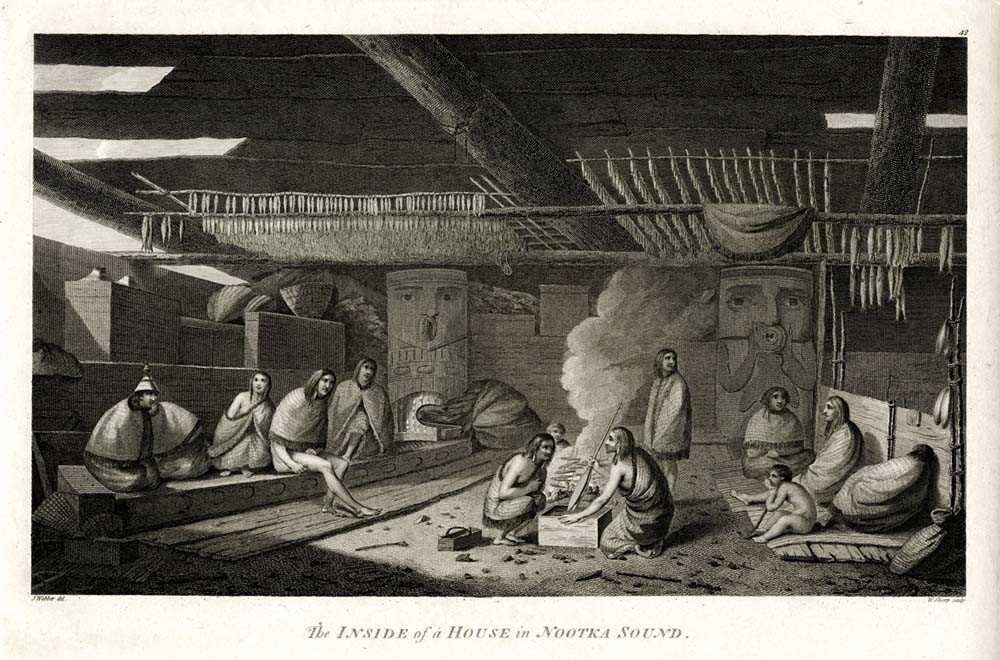

William Sharp, after John Webber The interior of a house in Nootka Sound 1784. Engraving. British Museum

Familiarity with the Nootka grew: 'We were daily among them, and lived in a manner in their Society. We saw their usual course of Life, and often mixed in their Occupations, or Amusements.'6 Although a trading post was not established, Walker's intrinsic interest in people and love of learning led him to build a valuable ethnological record, gathering much detail about Nootka life and adding significantly to vocabularies collected by Cook. Although he could see the profitable potential of the region's vast forests, Walker also foresaw that benefits to the indigenous inhabitants through European contact would be few.

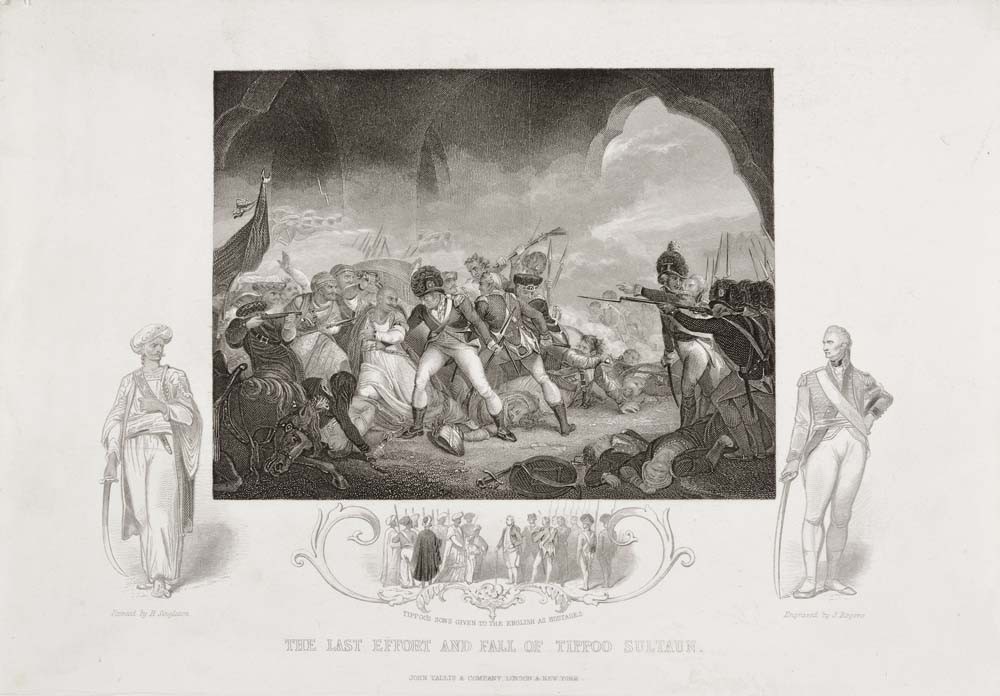

John Rogers, after Henry Singleton The last effort and fall of Tippoo Sultaun undated. Engraving. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery library archives

Rejoining the Grenadier Battalion at the Bombay garrison, Walker began his advance through the East India Company ranks. Promoted to lieutenant in 1788, he was adjutant in a 1790 expedition sent to relieve the Rajah of Travancore; in 1791 he was adjutant of the 10th Native Infantry in a campaign against the dreaded Tipu. In 1797 he became a regimental captain and was appointed deputy quartermaster-general of the Bombay army, with the rank of major. He became deputy auditor-general in 1798, and quartermaster-general in 1799, when he took part in the final war against Tipu at Seringapatam and their adversary was killed. Walker was awarded an honorary gold medal; the East India Company gained territory and valuable spoils.

Based on the west coast of India through the 1790s, Walker maintained his interest in observation and learning. Among his manuscripts and correspondence in the National Library of Scotland is a significant collection of his sketchbooks of people and ships of the Malabar Coast; Edinburgh University Library holds two large volumes of his drawings of Malabar plants and trees. A vast collection of Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit and Hindi manuscripts acquired during his years in India is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

In 1800, Major Walker was sent to the Mahratta states to bring peace to the region and reform to the ruling confederacy, aims that he achieved; a period of attendance on the commanding officer, Sir Arthur Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington), followed. In 1802, he was appointed political resident at the court of the Gaekwad of Baroda, with whom he later negotiated a defensive alliance. In 1807, he led an expedition into Kathiawar in Gujarat, where he succeeded in restoring order and, more notably, in ending the Jhareja Rajputs' customary practice of female infanticide.7 It was later said that 'his military achievements, his civil successes, sank to nothing in his estimation, compared with this nobler triumph. Be it remembered, too, that it was a victory ... solely effected by persuasion and reason.'8 Walker was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1808. The following year, when he returned to Gujarat, 'he was gratified by the visits of crowds of parents, bringing to him the children whose lives he had been the means of saving'.9 In 1810, he obtained leave to quit India in pursuit of a more settled life at his newly purchased Bowland estate near Galashiels and Edinburgh. He married Barbara Montgomery on 12 July 1811.

Sir Henry Raeburn Mrs Barbara Walker of Bowland 1819. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the Walker family 1984

Walker retired in 1812 and, as one biographer puts it, 'fixed himself in his native country, where he lived most happily in the bosom of his amiable family, attending with ardour to the varied pursuits of agriculture, and the improvement of his estates.'10 Two sons, William Stuart and James Scott, were born in 1813 and 1814. In these years, too, Bowland House was reworked by architect James Gillespie Graham in splendid Tudor Gothic revival style. Alexander and Barbara Walker's portraits were probably painted in 1819.11 The commission was likely arranged through Barbara's connections: Raeburn also painted her brother, Sir James Montgomery, second baronet of Stanhope; her sister-in-law, Helen Graham, Lady Montgomery; and her sister Margaret, with her husband Robert Campbell of Kailzie. Barbara's mother, Margaret Scott, had been painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Her father Sir James Montgomery, who was Lord Advocate from 1766, an MP and Chief Baron of the Scottish Exchequer from 1775 to 1781, had been painted by several artists.

Sanderson Stationer, Stow Bowland, Stow c.1908. Chromolithographic postcard. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery library archives

Sir James's obituary, in 1803, noted that Barbara 'had devoted herself to attendance upon the declining years of her father, in preference to the formations of other connections'.12 Her marriage eight years later, at the age of forty-one, must then have been unexpected, as would have been the births of her two sons. Her recently cleaned and conserved portrait is fresh testimony to the power of Raeburn's art. Like Alexander's, her watchful gaze is both direct and reticent. A spectacularly well painted gold chain adorns pale shoulders and a stately bust, from which silvery fabric tumbles in fashionable Regency lines.

Bowland House, with its many Indian curiosities, 'notably of representatives of the Hindoo pantheon',13 was an ideal setting for Walker to work on his various Indian histories, and his accounts of Indian customs and beliefs. He also revisited his concerns about Britain's role in India, adding to the thoughts he had penned in 1811 during his passage home.14 Noting then that the East India Company, with its 200,000 men, was £30 million in debt, he reflected that British power in India was 'maintained at the expense of the parent state... guaranteed not only by the blood but the treasure of England'.15 In a private correspondence from 1817 to 1819 he built a compelling case for 'an unusual and unpopular expedient. A proposal to contract the bounds of our territories, and to relinquish the fruits of conquest...'16 Although opening the argument with fiscal concerns, Walker's proposal for radical reform broadened as he acknowledged a deep-rooted hostility and degrading dependence among the subjugated Indian populace: 'We have left wounds in every quarter, and produced everywhere discontent: the confidence which was once reposed in our moderation and justice is gone. We have made use of treaties, contracted solely for protection, as the means of making violent demands... Every individual almost above the common artizan and labourer suffers by our system of government.'17

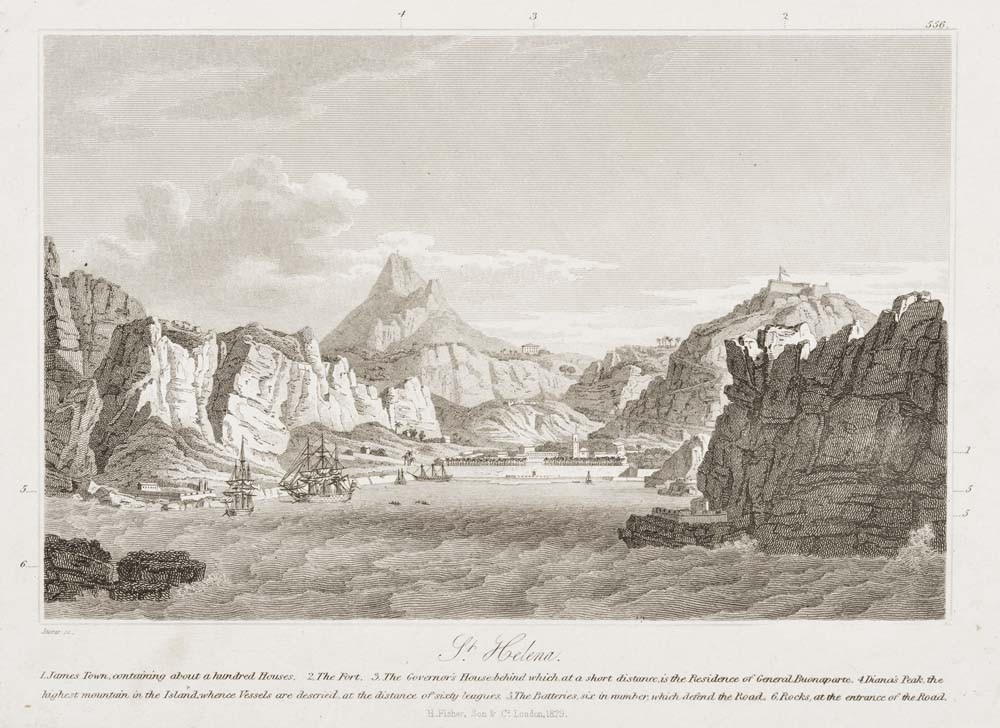

Son & Co. London St Helena 1829. Engraving. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery library archives

In 1822 Walker was coaxed from retirement to become governor of St Helena, then still under East India Company rule. Arriving on the island as a brigadier-general on 11 March 1823, almost two years after Napoleon's death there in exile, he lived at Plantation House, the governor's residence, perched high on a hill above the capital of Jamestown. There he remained active, 'promoting schools and libraries, improving the agriculture and horticulture of the island, by the formation of societies, the abolition of slavery, and the amelioration of the lower classes'.18 The phased emancipation of the island's slaves occurred between 1827 and 1832 (slavery was abolished in British colonies in 1833). He also continued with his writing, including revisions to his North American manuscript. Failing health, however, brought on by an apoplexy from which he never fully recovered, meant a return to Bowland in 1828; Walker died in Scotland on 5 March 1831. Barbara died the same year.19 Alexander's full correspondence on British rule in India was published in the House of Commons papers in 1832. Its incisive contents, if heeded, would have changed history.