B.

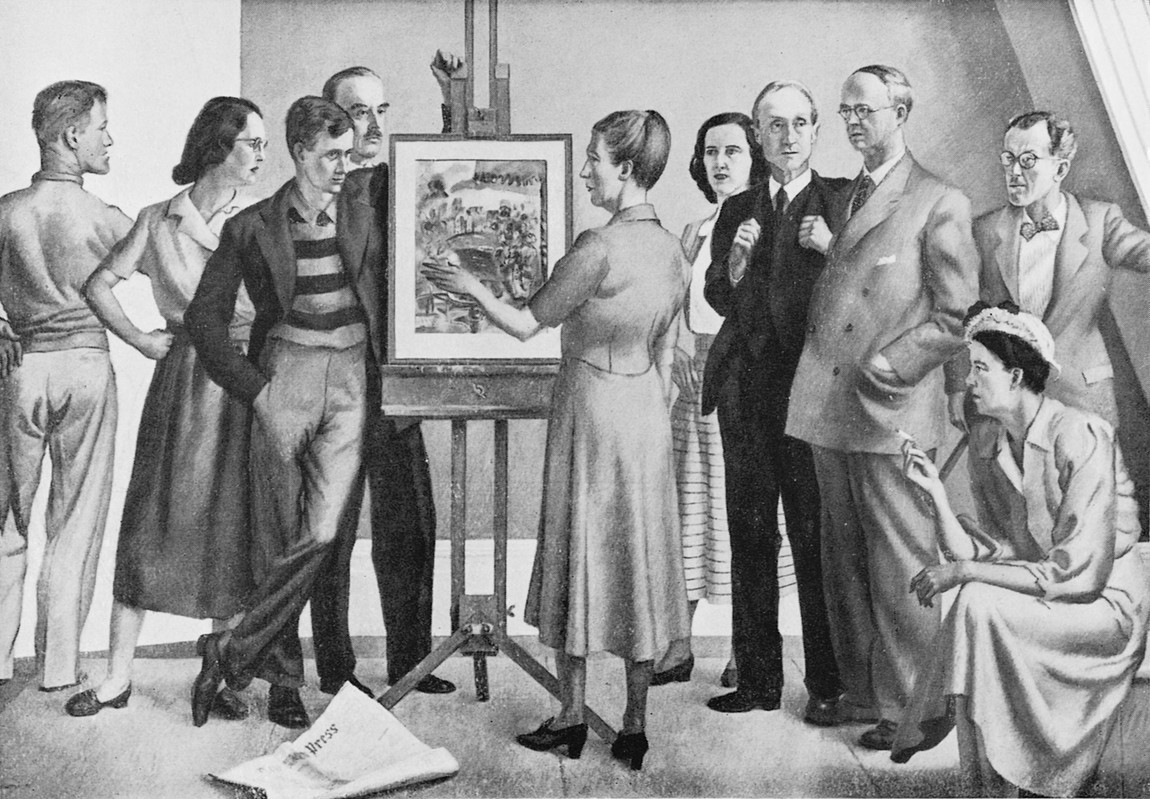

Belgian Refugees by Frances Hodgkins

Collection

This article first appeared in The Press on 28 February 2007

Belgian Refugees is one of the first oil paintings that Frances Hodgkins ever exhibited, although at the time she was already well accustomed to showing her watercolours. Working in oils and tempera on canvas, she used an experimental technique in this work that gained much from her experience with watercolour. Believed to have been first shown as Unshatterable, in October 1916 at the International Society's Autumn Exhibition in London, the choice of title would suggest a greater sense of resilience than is actually conveyed by this family group. Here only the baby is oblivious to trouble, while his nursing mother seems devoid of expression, and the older children tense with anxiety or fear. Behind the group, a gap in the swirling grey suggests the fact of a missing father, and this steam and smoke speaks of displacement, the atmospheric backdrop of a train station or the symbolic clouds of war. Within the wall of monochrome, intense colour is reserved for mother and child, who also remind of one of Hodgkins' favourite early choices of subject matter in watercolour.

Frances Hodgkins Belgian Refugees 1916. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with the assistance of the National Art Collections Fund, London 1980

Born in Dunedin in 1869, and destined to become one of our best-known expatriate artists, Frances Hodgkins had left New Zealand for her third and final time in October 1913, and spent most of the following year painting and teaching her way through Italy and France. Intending to make her permanent base in Paris, the outbreak of war in August 1914 had sent her packing to England. Though herself a refugee of sorts, she was also aware that her own difficulties were insignificant in comparison to those of others. On 15 October 1914, Hodgkins wrote to her mother in Wellington "It has been a black week. The fall of Antwerp a great blow ... The misery and horrors are too awful - Belgium is a mere skeleton of herself, two thirds of her population are flocking to England, penniless and starving ... We live from day to day ... normal life is quite upset[,] ones centre of gravity queerly shifted. I envy the people with something definite to do." In a lighter vein, she continued "Any woman who can say "Avez vous famm [sic]?" is allowed to snap up a Belgian refugee and cherish them. One smiles at these things in order not to weep for the tragedy is heart breaking."

Germany had declared war upon France in early August, demanding also that Belgium allow the passage of troops through their country for ease of attack. Belgium's refusal, however, resulted in targeted, systematic slaughter and a wave of destruction on its populace, with hundreds of thousands displaced - over a million to Holland and a quarter of a million to Britain. While refugees poured into English towns and villages, hostels and committees were established to support them. In her own desire to be useful, Frances Hodgkins set to work knitting scarves - perhaps not as odd or unlikely as this sounds - although her offer to a nearby Red Cross hospital to work as a Secretary was not taken up.

From November 1914, and over the next few years, Hodgkins based herself at St. Ives in Cornwall, a location long favoured by artists. An effect of war, however, meant she was largely restricted to working indoors, as security concerns forbade artists from coastal sketching. This ban resulted for her in an increase in portraiture, and works such as Mr and Mrs Moffat Lindner and Hope (1916, Dunedin Public Art Gallery), Loveday and Anne (1916, Tate Gallery), and Belgian Refugees. That this work dates from 1916 is probably confirmed by a letter she wrote to her mother in September from Gloucestershire, in which she records that although she was exhausted from teaching, her students were soon to leave, and she was concentrating upon finishing works for the October exhibition in London, where this work was shown. This timing also coincides with the disastrous Battle of Somme, which started in July 1916, and in 4½ months would result in 800,000 men from the Allied forces losing their lives - possibly further inspiration to Hodgkins for this particular kind of paintbrush action.

Unlike her contemporary the German artist Käthe Kollwitz (whose work Belgian Refugees recalls), Hodgkins hardly allowed her experience or the events of war to be reflected in her art. Apart from this work, just a few watercolour paintings on a similar theme by Hodgkins are known. While Belgian Refugees shows her clearly capable of making a powerful and compelling anti-war statement, this was evidently not a direction she would be cornered into. The need to sell work in order to survive was probably part of this, but she was also clearly motivated to apply her gift in a different direction. Leitmotif, the generous survey exhibition of her work recently shown at Christchurch Art Gallery, proved Hodgkins' preference for capturing intimate, idyllic scenes or moments, and for expressing her pleasure in the exuberant possibilities of paint. Focusing on the period in which she was at the height of her reputation, it gave a rare opportunity for appreciation of her prolific output and individual brand of genius. From the late 1920s until her death in 1947, Frances Hodgkins was considered to be a leading British painter, and was even selected to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1940 (to eventually be assertively reclaimed by New Zealand as its own). Belgian Refugees, a major early work by Hodgkins that displays all of her ability and promise, is on display in the Permanent Collection Galleries.

Ken Hall