Tomorrow, Book, Caxton Press, Landfall

Publishing and the visual arts in Christchurch, 1934–51

In the decades before and after the Second World War, Christchurch experienced a remarkable artistic efflorescence that encompassed the visual arts, literature, music, theatre and the publishing of books and journals. And the phenomenon was noticed beyond these islands. For instance, in his 1955 autobiography, English publisher and editor of Penguin New Writing and London Magazine, John Lehmann, wrote (with a measure of exaggeration, perhaps) that of all the world’s cities only Christchurch at that time acted ‘as a focus of creative literature of more than local significance’. 1

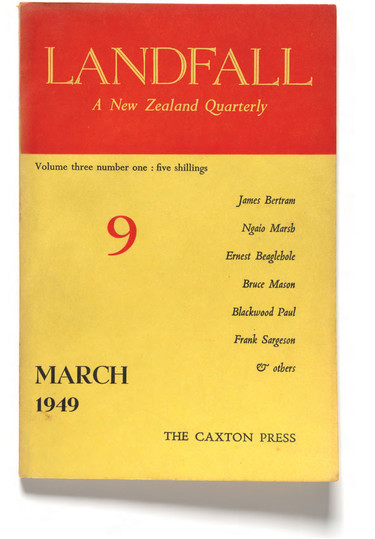

Not all the writers Lehmann had in mind (who included Ursula Bethell, Denis Glover, Allen Curnow, Frank Sargeson, A.R.D. Fairburn, R.A.K. Mason, Charles Brasch and James K. Baxter) lived in the city—several were Aucklanders, Baxter lived in Dunedin, Brasch in England. But importantly, all were published in Christchurch, by Glover’s and Leo Bensemann’s Caxton Press.

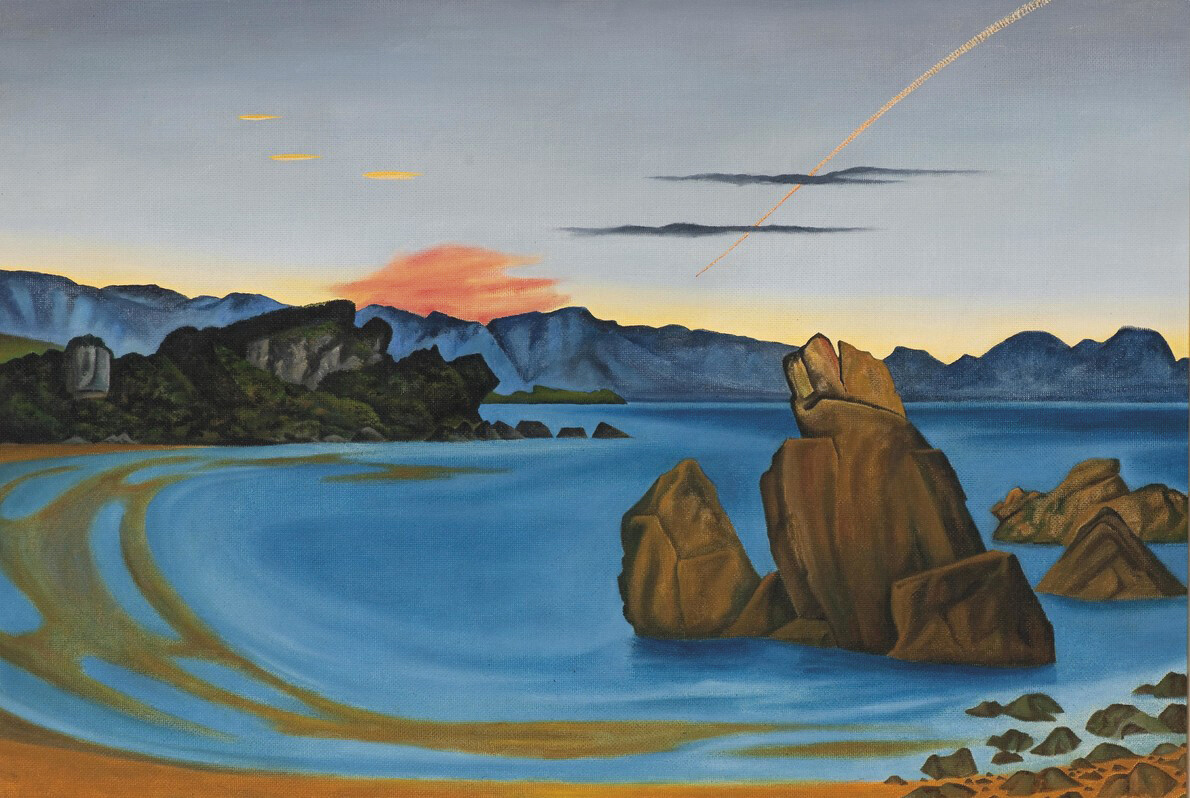

Lehmann’s comments refer to literature (and particularly poetry), but they can be applied equally to what was being achieved in composition by Douglas Lilburn, in Shakespearian production by Ngaio Marsh, and in painting by artists of The Group.2 Founded in 1927, The Group, like Caxton Press, was a focal point for artists around the country, and especially, but not exclusively, South Islanders. The flowering of the arts in Christchurch had a local habitation through these institutions but was essentially a national phenomenon.

The above assertions require more space than is available here to explain and fully justify. Suffice to say in the present context that the situation involved a combination of talent, luck, accident, mutual stimulation, a sense of shared circumstances and opportunities, the pressure of history both national and international, and an element of the always inexplicable. 3 In this article I focus on a few points of crossover between publishing and the visual arts, because it is at these intersections (and others like them involving theatre, poetry and music) that the phenomenon of a collective irruption, transcending specific genres, is most evident.

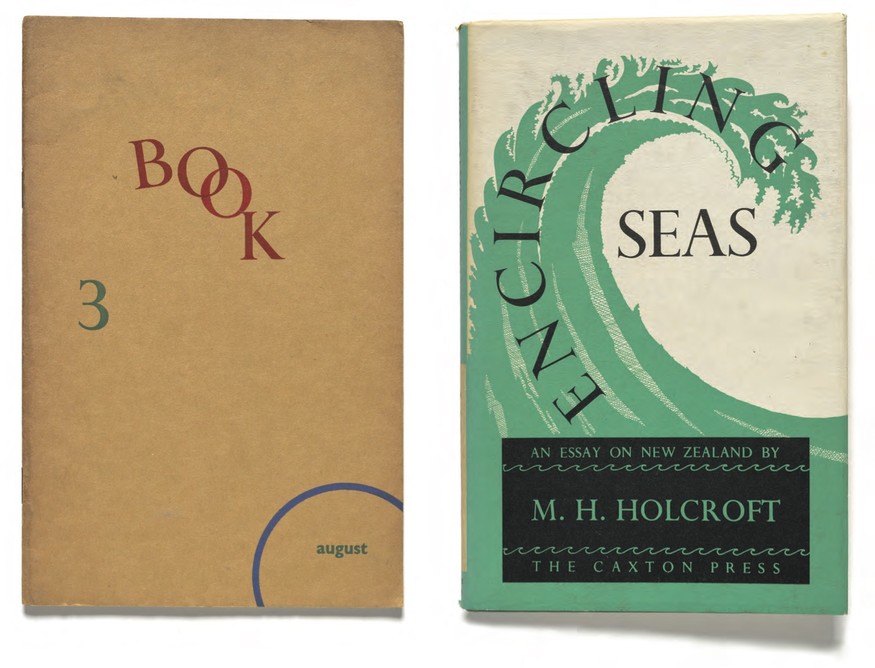

Denis Glover (ed.), Book 3: A Miscellany from

the Caxton Press, Christchurch, Caxton Press, August 1941. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives, Peter Dunbar Collection

M.H. Holcroft, Encircling Seas: An Essay, Christchurch, Caxton Press, 1946. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives, Leo Bensemann Collection

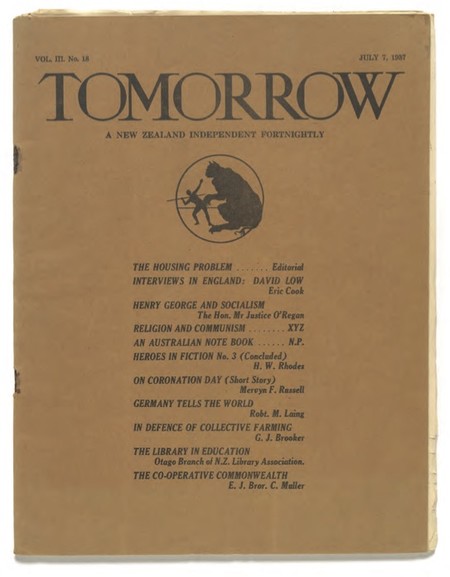

Kennaway Henderson (ed.), Tomorrow: A New Zealand Independent Fortnightly, vol III, no.18, 7 July 1937. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives, Peter Dunbar Collection

Tomorrow, 1934–40

In the 1930s literature and the visual arts followed separate but parallel tracks; it was only at the end of the decade and in the 1940s that significant crossovers occurred. The two most significant venues for literary output in the 1930s were the journal Tomorrow (1934–40) and the Caxton Press, which was founded in 1935. A crucial link between the two was the poet and printer, Denis Glover (1912–1981). Glover (and John Drew) founded the Caxton Press as an independent printer and publisher after two years as a university club; he was also on the editorial board (with Frederick Sinclaire and H. Winston Rhodes) of Tomorrow, contributing prolifically to its pages with poems, stories, essays and reviews.

Not surprisingly, a close relationship developed between the Caxton Press and Tomorrow. Many writers published by Caxton also wrote for the journal;4 Tomorrow regularly reviewed Caxton publications. The closeness of the two outlets is most explicit in the Caxton anthologies Verse Alive I and II (1936 and 1937), edited by Glover and Rhodes, which collected satirical verses first published in Tomorrow.

Nevertheless, there was a difference in approach. Tomorrow was indisputably left-wing and internationalist in outlook; its main preoccupations were the crisis of capitalism, as reflected in the Great Depression, and the rise of fascism in Europe. Caxton, on the other hand, while sympathetic to left- wing concerns, was more focused on cultural nationalism, and the establishment of a native literature written by New Zealanders, for New Zealanders and about New Zealand.

Tomorrow’s nominal editor was Kennaway Henderson, who contributed pointed, if rather crude, full-page cartoons on political subjects to each issue, but otherwise left the running largely to the young radicals on his editorial board. Despite Henderson’s vocation as illustrator, Tomorrow manifested relatively little interest in the visual arts—the few exceptions included articles by Brasch (visiting from England) on a touring exhibition of British art, by Margaret Anderson on a Wellington exhibition of children’s art, and occasional columns of comment by Fairburn. 5 Sometimes an artist would contribute to debate about an art-related topic. The sculptor Francis Shurrock and the painter Toss Woollaston had an extended exchange in which they rather talked past each other about the relationship of life and art. Shurrock advocated a collective view of the arts including government assistance,6 while Woollaston argued for the inevitable opposition between the individual and bourgeois culture, which were necessarily ‘at war’.7

But the presence in Christchurch of The Group as a lively alternative to the conservative establishment of the Canterbury Society of Arts passed entirely without comment in Tomorrow, as did the sudden emergence and disappearance of the New Zealand Society of Artists, which briefly subsumed The Group in 1933–1934.

The absence of art commentary in Tomorrow presumably reflected the predilections of Sinclaire, Rhodes and Glover, who were all more directly concerned with literature, politics and international affairs.

Caxton, Book and The Group

In the beginning, Caxton largely reflected Glover’s commitment to poetry. Most early books were small volumes of verse by Curnow, Glover, Bethell, Mason, Brasch, J.C. Beaglehole and Fairburn. But in 1937 Caxton broadened its range into visual art with the publication of Leo Bensemann’s startlingly original Fantastica: Thirteen Drawings. Helping out, Bensemann demonstrated such natural aptitude for printing that Glover and Drew offered him a third partnership in the Press. Concurrent with joining Caxton in 1938, Bensemann also joined The Group, thus forging a crucial connection between the leading progressive institutions for literature and the visual arts. With Bensemann on board, Caxton showed more interest than previously in the visual content of their books.

A case in point is Curnow’s Not in Narrow Seas (1939), a demythologising history of Canterbury in prose and verse. As well as a strikingly modern three-colour typographical cover (vertical lettering, sans serif types), it included a clever frontispiece drawing by Bensemann in keeping with the anti-colonial theme of the text. He also contributed drawings and engravings to other Caxton publications including the innovative A Specimen Book of Printing Types (1940), in which Caxton first staked its claim for excellence and innovation in typography (there was a second such specimen book in 1948).

The alliance between Caxton and The Group was reinforced from 1940, with all subsequent Group catalogues being designed and printed at Caxton and becoming— especially after Bensemann arrived at his distinctive tall and narrow format from 1945—what Spencer Bower called ‘a definite feature ... they showed all the skill of the printer-artist.’ 8 Furthermore, in the 1940 Group Show, as if to confirm typography as a legitimate member of the team, Caxton appeared as an exhibitor alongside Group regulars Woollaston, Angus, Bensemann, Spencer Bower, Colin McCahon and others.

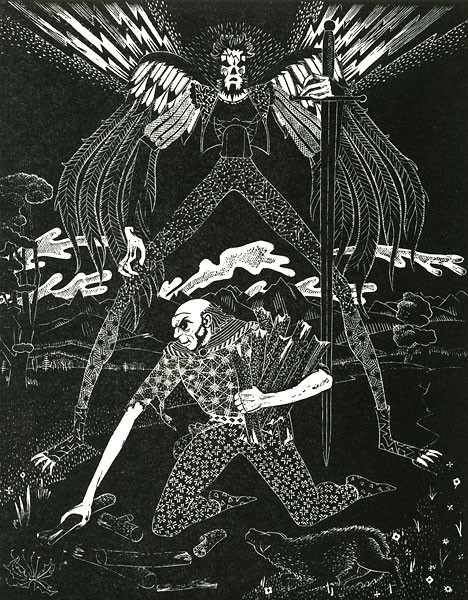

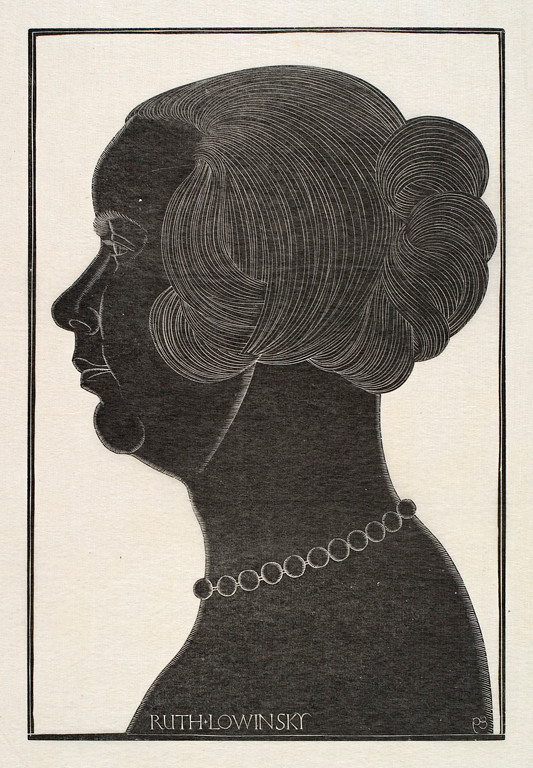

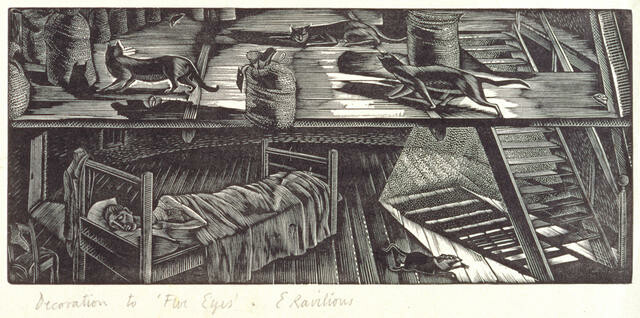

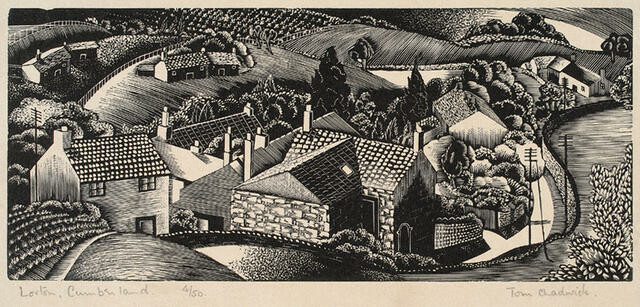

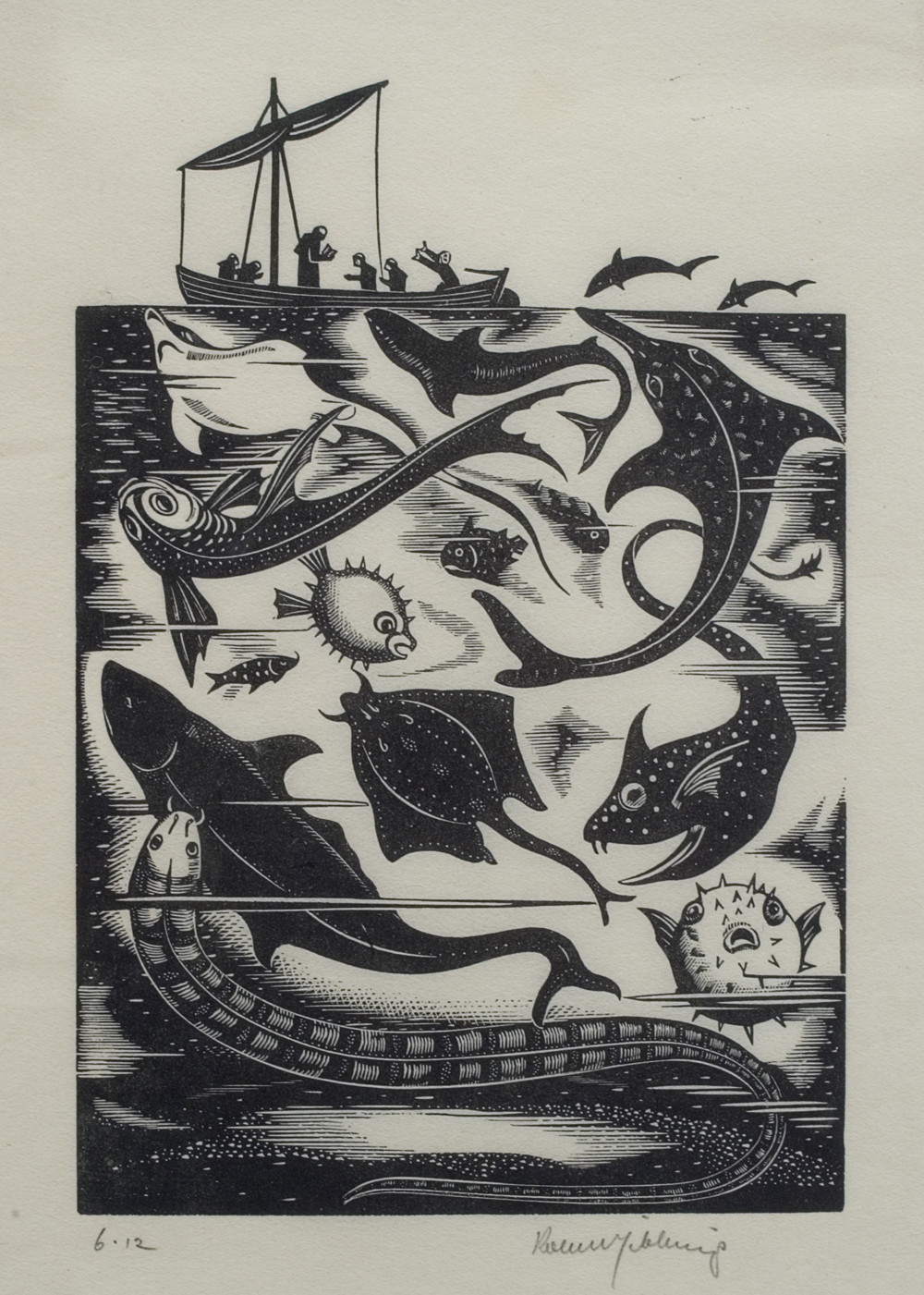

In 1941 Caxton created an opportunity for further exposure of visual material in Book: A Miscellany, of which six lively numbers appeared in 1941–2, and a further three in 1946–7 after Glover’s return from the war: ‘BOOK will contain stories, articles, criticism, poems, art, typography—in fact, anything we can find that is likely to be of interest.’FTN_9 Book was something of an in-house journal for Caxton’s core writers, so it is hardly surprising that Bensemann’s work figures prominently with illustrations, engravings or bookplate drawings by him in almost every number. Other artists were also represented, however: there were drawings by Jean Angus, Rita Angus and Graham Kemble Welch, and wood engravings by W.H. Allen, S.B. McLennan, Shurrock and E. Mervyn Taylor. In Book 5, Rita Angus contributed superb full-length portrait drawings of Curnow and Glover.

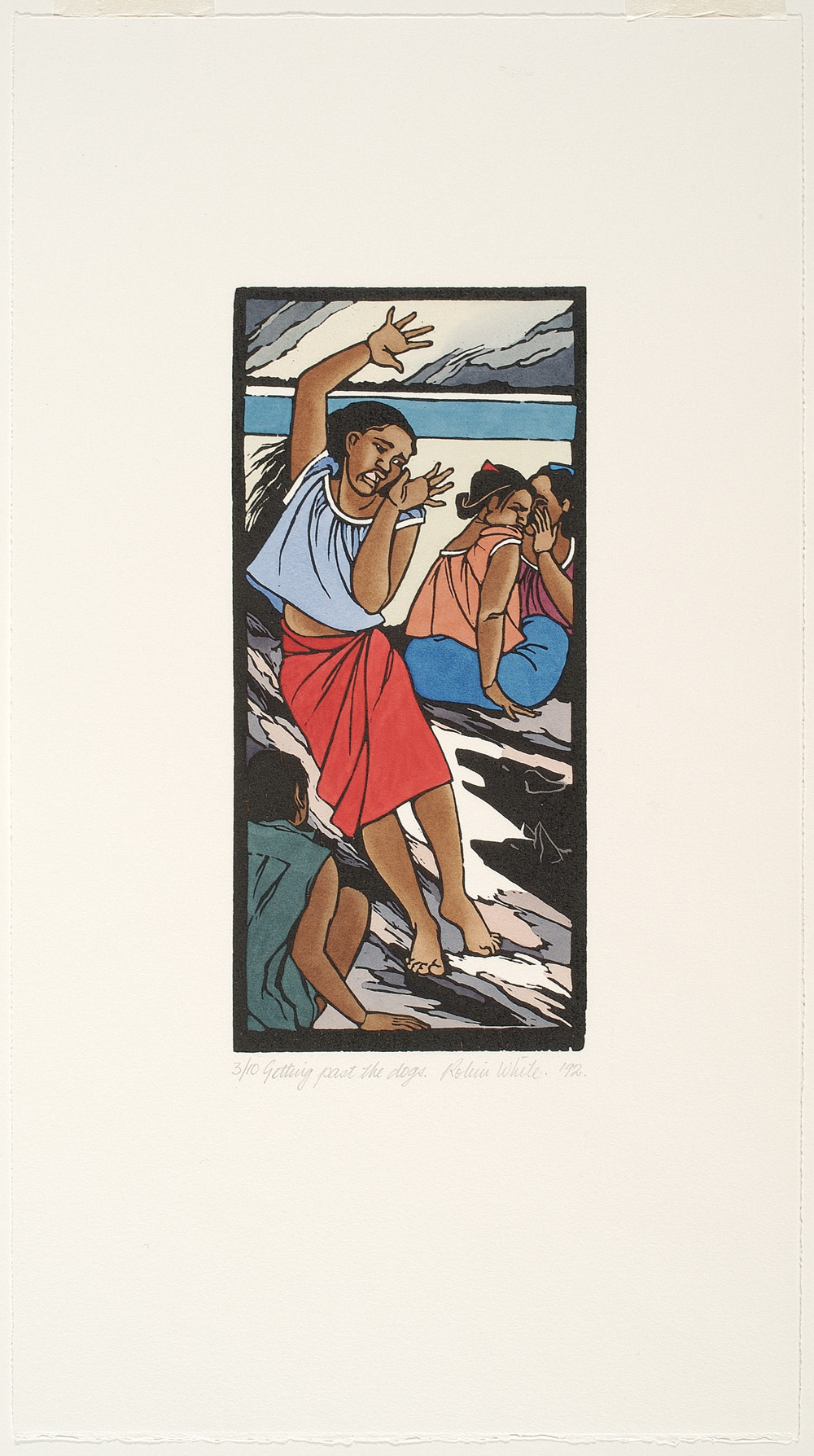

Caxton’s book covers were predominantly typographical, but occasionally more pictorial covers were adopted such as Vernon Brown’s fern-frond design for Sargeson’s A Man and His Wife (1940), Bensemann’s Japanese-influenced cover for Holcroft’s Encircling Seas (1946), and the fantail cover for Mervyn Taylor’s Wood Engravings (1946), for which the engravings were printed from the artist’s original blocks.