Talking Bensemann

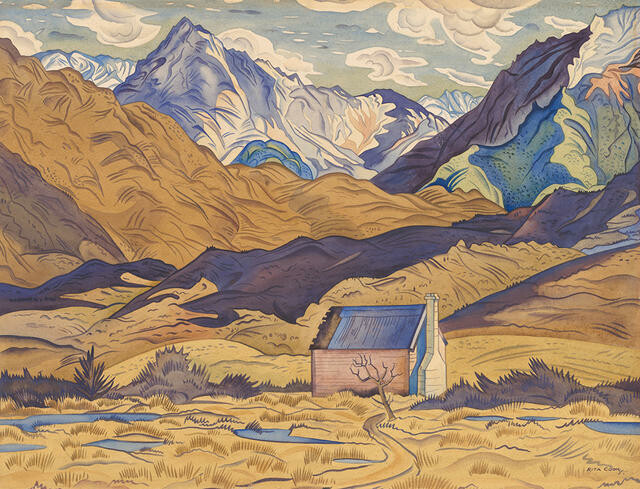

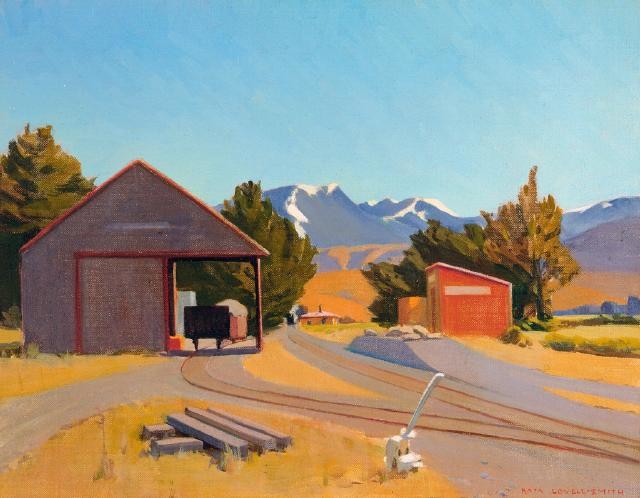

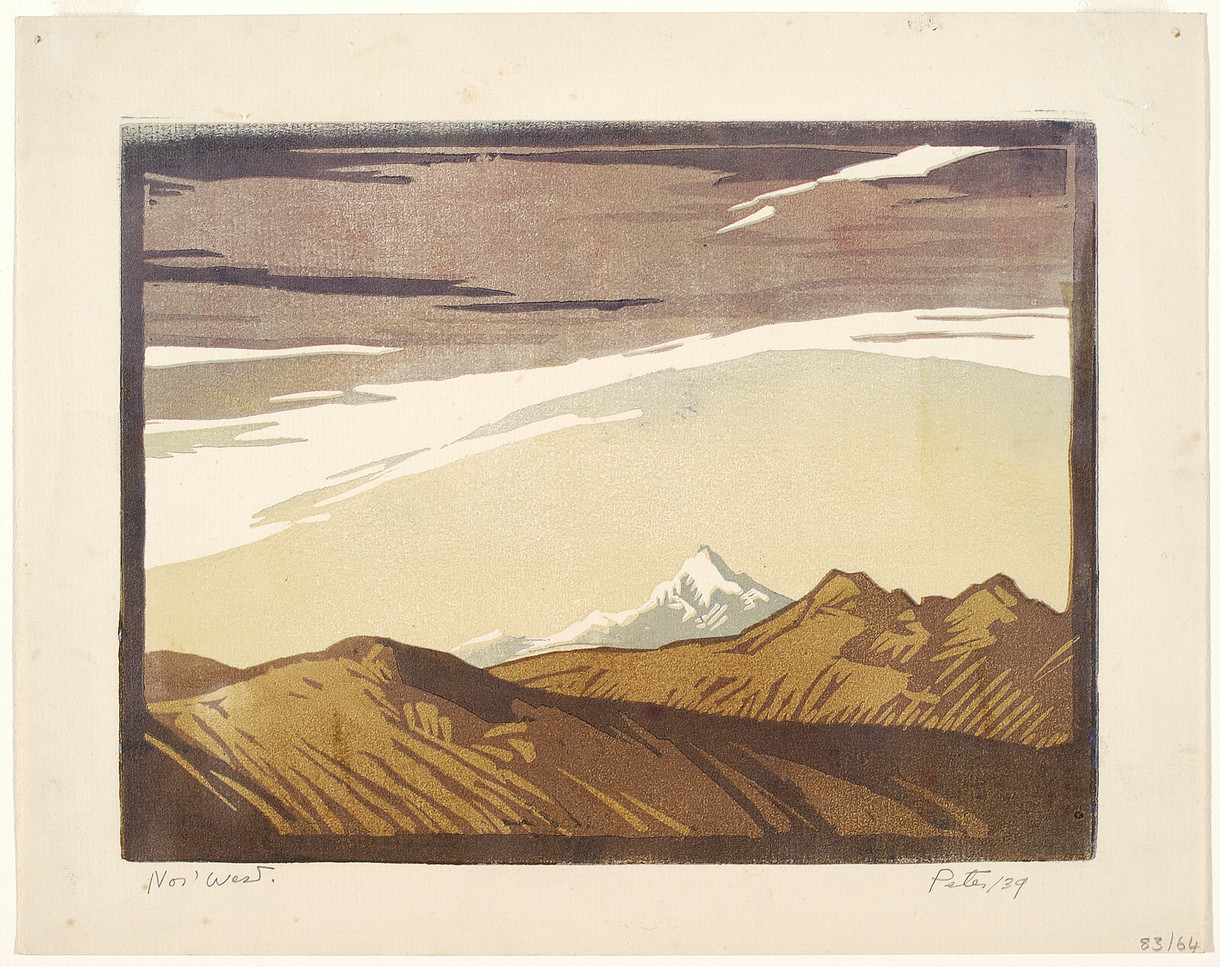

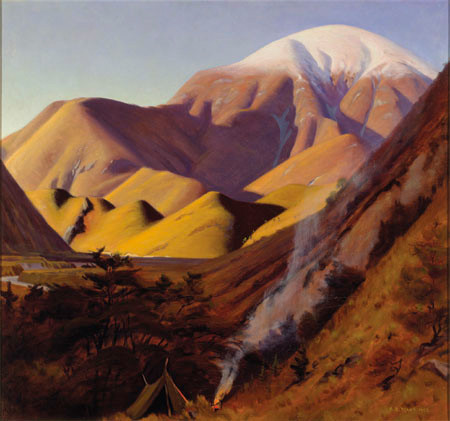

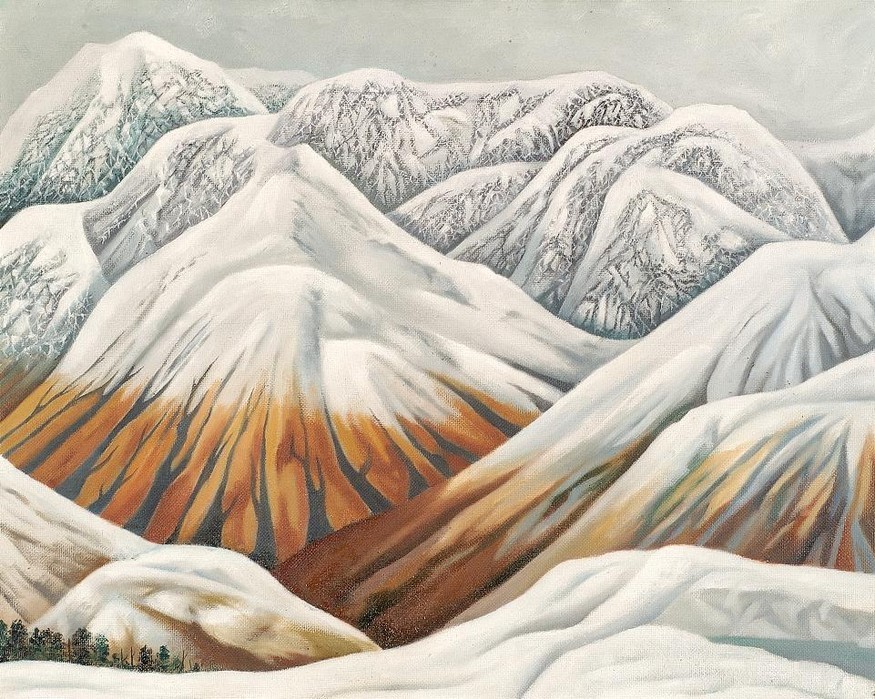

Leo Bensemann Pass in Winter 1971. Oil. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Harry Courtney Archer estate 2002. Reproduced with permission

Leo Bensemann was one of the most respected figures in the Christchurch arts scene, and played a pivotal role in influential arts collective The Group. Always something of an odd-man-out, he produced a large body of work across several different disciplines before his death in 1986. In an attempt to get a fuller picture of the man himself, Gallery director Jenny Harper spoke to two artists who knew him well, John Coley and Quentin MacFarlane.

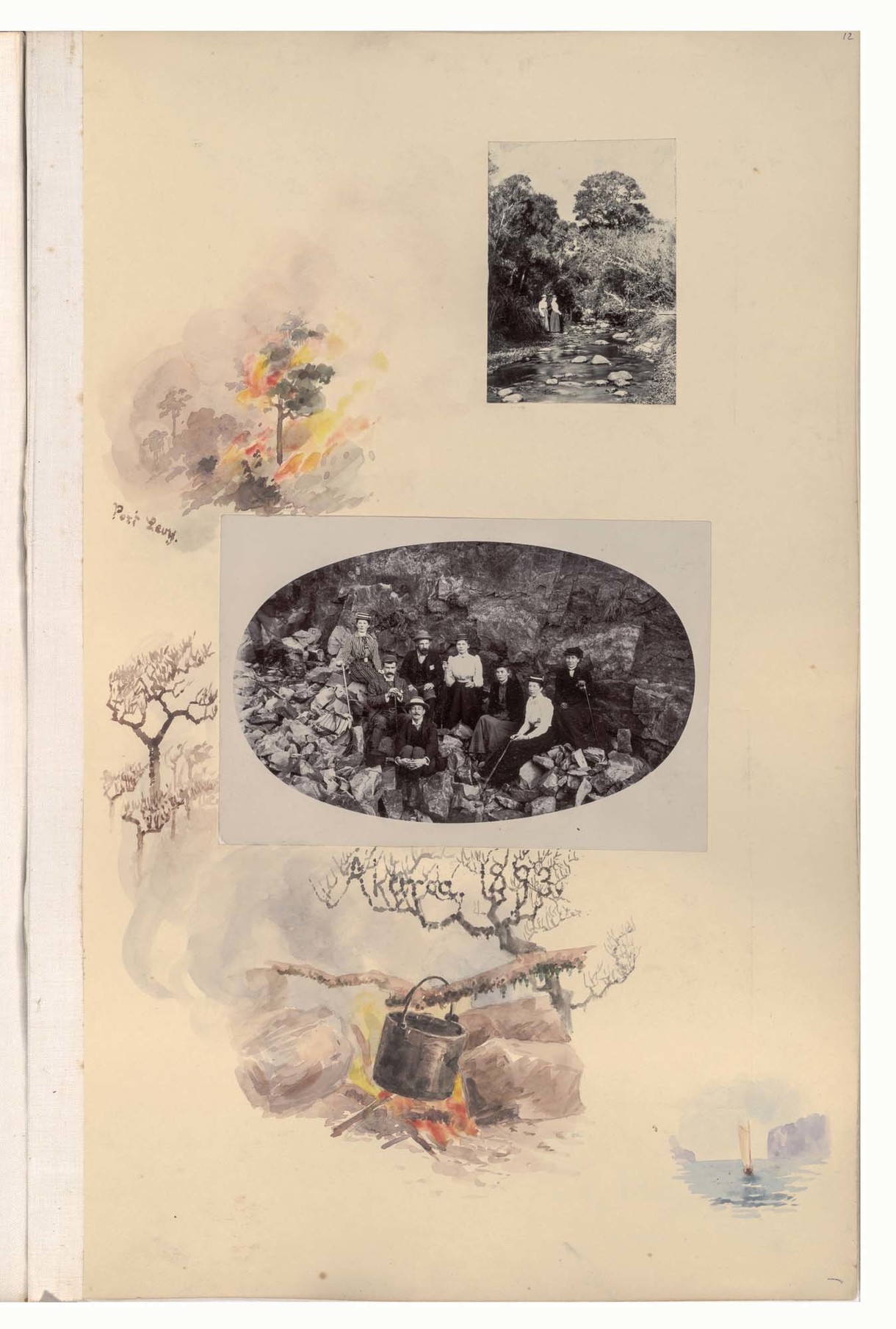

Leo Bensemann Self Portrait 1938. Oil on canvas. McLaughlin family foundation, New York. Reproduced with permission

Jenny Harper: How did you first come to know Leo Bensemann? As art students in Christchurch during the 1950s, were you particularly aware of his presence or reputation in the city's arts scene?

Quentin MacFarlane: I went to art school in 1954, a year ahead of John, and probably met Leo at a Group show, because otherwise there was no reason for us to go to The Caxton Press. At the time he would have been about forty-three. We got to know him and a number of other senior artists through Bill Sutton during our art school years, and they became our friends.

John Coley: I came from Palmerston North into what was a fairly vibrant cultural scene in Christchurch. The thing I noticed was that there was not only a colony of established artists, an amazing group of art students and a large, supportive arts community, but also a number of European émigrés—people like Rudi Gopas, Frank Gross and André Brooke. It was an interesting and exciting time.

Leo was highly respected and had a long history of cultural activity in the city. He was associated with Rita Angus and Doris Holland, was a leading member of The Group and was a noted typographer and print designer. Although a third-generation New Zealander, he was of German heritage, and I felt he was more in tune with the group of recent arrivals from Europe. They had a different attitude to the kind of received English-oriented tuition of the art school. They would gather in coffee shops and argue about art, books and ideas generally.

JH: John, you and Bensemann both painted each other's portraits—what was he like as a sitter? And conversely, how was it sitting for him?

JC: Brian Muir, director of the Robert McDougall at the time, devised an exhibition called Canterbury Confrontations for the Pan Pacific Arts Festival. A group of local artists drew names out of a hat to be paired to paint each other. Carl Sydow exhibited an X-ray of Alan Pearson's skull while Pearson made a fine oil study of Sydow. I drew Leo's name and he drew mine and, although I had only done one head study since leaving art school, Leo came to sit for me. But he would have been on the sauce the night before and he'd nod off—his head would slowly droop, and I would actually have to follow him down drawing as I went. When he realised I was having a struggle he gave me some extra sittings. But I got the portrait done; it's now in the Gallery's collection.

In his portrait of me I feel Leo got my essential character somehow—sort of a hawk-like bird peering out, looking stern but soft centred. Leo gave me the portrait, and we called it the 'Ayatollah Coley' in our family because of its resemblance to the Muslim cleric.

JH: As one of the older generation of artists in The Group, what did you feel his attitude was towards younger members?

JC: We always appreciated Leo's praise when it came because we respected him greatly—he carried with him a kind of aura of knowledge and good judgement. He had a tremendous work ethic but he lived a fairly robust life as well. We used to marvel at his capacity to out-drink people and yet maintain his equilibrium and his intelligence. He was always interested in and encouraging of the younger artists. The Group shows were a great attraction when I came to Christchurch as a student. Later, as a young man, to be invited to join The Group was a tremendous honour.

QM: When we joined The Group it was quite strange. There were divisions in it, and I think that some of the older artists resented the younger members (we were probably fairly pushy, being in our twenties) but Leo had our absolute admiration and was really keen on revitalising things. Of course, there were other people who championed the young too—Frank Gross was very warm hearted—and you soon got to know who these people were.

JC: They always popped around to see you at work, and have a talk to you about art.

QM: There was also the so-called 'boozing' culture. But going to the pub after work was going to see your friends and talk about art in general—it was part of Christchurch's great strength, that people did get together. Leo and his printers' circle would drink a couple of beers... they'd let the beer go flat and then drink it, and then they would follow that with what they called 'stingos'—double whisky and water. In those days of 6 o'clock closing we would meet for a drink at the Market Hotel and all those rat bags would be in the back bar waiting for the pub to close so they could carry on behind closed doors after 6pm.

JC: The Market meetings were great tutorials actually. You could learn a lot from those fellows. I certainly did.

Leo Bensemann Albion Wright 1947. Oil on canvas on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, N. Barrett Bequest Collection, purchased 2010. Reproduced with permission

JH: What was Bensemann like?

QM: I always regarded him as fairly reserved, but years later I realised that he was quite a shy man.

JC: He had a tremendous intellectual integrity and he was very much his own man. He wouldn't be swayed by any 'ism' or movement or strong influence that came through. Perhaps Rita Angus had an influence on him, but he really followed his own path, which was actually dictated by kind of a north German rigour and craftsmanship. Although Leo was born in New Zealand, he had strong ties with the region around Hamburg and it influenced the style of his work. You can see quite a Grimm Brothers' fairy-tale fantasist in his illustrations.

QM: Those wonderful pencil drawings, they just take your breath away. And the sense of craftsmanship that he carried with him, that was one of the reasons you respected him, because he was self taught in almost everything he did. I don't believe he ever attended a school of typography—I think he learned that on the job at The Caxton Press. I could be wrong there, but he certainly had an exquisite sense of design. He also taught himself to play the guitar, and was a very skilled classical guitarist. In fact, classical guitar performers giving concerts would stay with Leo. He would make them welcome and they respected him. He played an enormous range of music really.

JC: Leo's generation were born around the First World War, brought up in difficult times when options were restricted. Quentin's and my generation had much more freedom in the post-War 1950s. Leo and the older artists appeared very mannerly, courtly almost in their interactions—a hint of Edwardian virtues. They had pretty good parties but were always in control. I think of them in well-tailored tweed jackets, Viyella shirts, knitted or club ties, Bedford cord trousers, desert boots—Rex Harrison, Michael Redgrave sort of chaps. Of course, Leo could get quite acerbic and you didn't want to get on the wrong side of him—he could bite back sharply if something especially provocative was said. His eyebrows would get lower...

QM: They would join in the middle.

JC: ... and he would point his pipe and then shake it at the offender and say something like, 'Do you really believe that? That's nonsense! Now think of this...' He wouldn't let a fuzzy idea go unchallenged, but he would never hold a grudge. But I used to worry about him. I worked nearby at the Teachers' College, as indeed did Quentin, and I used to go to the Post Office over the road and I'd see ambulances going into the Caxton. And I always thought they would be there to pick up Leo and take him to hospital because I didn't know how a human being could sustain the kind of life that he led. I mean, he drank a lot of beer, or appeared to, and certainly worked till late. So I thought he was due for a heart attack. He said, 'You always seem to show great interest in my health, John', and I said 'Well I see the ambulances going in and I get terribly frightened that one might be for you dear chap'. To which he replied, 'John, they are going to the automotive repair place next door to check up on their internal electronics.'

QM: I'll give you an idea of what it was like when we went to the pub. We used to drink at the Market Hotel—all the artists used to go there—until they pulled the building down and we moved up to the New Albion, which was a family pub opposite Johnson's Grocery in a little village-like enclave in Colombo Street. There would be Leo talking with Bill Sutton, Norman Barrett, myself, Trevor Moffitt, you sometimes...

JC: Trevor Moffitt was more a regular than me.

QM: And in would walk the stork-like figure of Rudi Gopas, forever smoking the same cherry-wood pipe. The artists talked about art, intermingled with people whose conversation centred around North Canterbury. Leo was inclined to get brisk with Gopas, and the situation would be managed by a gentlemanly Mr Barrett, with Bill offering advice from the sideline. There was never a punch-up.

In the sixties and seventies, Leo would be wearing quite stout open-necked shirts with shorts; sometimes in the winter he would have a collar and tie with a tweed coat and corduroy trousers. He hadn't really changed from the thirties. And he would be wearing these Riekers, but he had a curious sort of way of tying them up on the side (they didn't have the laces on the front down the middle) that was very Germanic.

JC: The strange thing about Leo was that although he had been born here, he still had a strong spiritual connection to his ancestral homeland. There was no doubt that, to us as young people, he was in a way as foreign as Rudi Gopas or André Brooke were. Wonderfully exciting men because through their example, work and conversation they were enormously influential. Leo seemed to be a latter-day European immigrant in a way—and greatly respected. He could speak German, and certainly read it. He had studied with his mother and probably his grandmother. He had a broad cultural view that seemed to be characteristic of the German migrant families in Nelson.

In Leo's time, and indeed today, only a small percentage of artists could live comfortably from painting alone. In his case it was printing that provided for his family, his wife and children.

JH: Did you ever visit him at The Caxton Press?

QM: Once or twice I had to go around to the Caxton to pick up the invitations, which always amazed me. We would take a handwritten copy around and he would handset the whole thing—he must have worked through the night to get the Group Show catalogues done.

I actually got to know Leo in a slightly different way when I first began teaching in Christchurch during the 1960s and taught three of his children. There were two girls and a boy, and I got to know Leo as a parent, as well as a well-respected friend. I set up the school magazine and I had to take all the copy over to Leo and he was wonderful. He would be there standing behind the typesetter's 'stone', as they called it, and was always so helpful. He never got flustered.

He used to work for Bullivant's—the big advertising agency and printery—doing graphic art so it was quite a big move for him to go to Caxton, which certainly struggled in its early years. It had a bravely liberal reputation, taking chances on new novelists, poets, journals. Caxton published Landfall and Acsent.

JC: There was lot of heart in that business—everyone at Caxton took great pride in their work, largely due to Leo's and Dennis Donovan's attitudes and leadership.

JH: Well, are there any good stories about Group shows or openings that you could share with us?

JC: They were a great annual affair, the star show of the year, really. All the Canterbury Society of Art shows were seasonal ones, but then here was this marvellous show where artists invited their peers to exhibit with them, exposing all this new talent. You could come from anywhere: Colin McCahon, a member of The Group, might recommend Janet Paul and so she would send a number of works. A Group show was really a collection of self-curated one-person shows. One of the characteristics of the arts scene in Christchurch at the time was that you had this big exhibition space, the CSA, but no one artist could fill it adequately in a solo show without working for three or four years, so the alternative was to exhibit in the CSA group exhibitions. The Group had been formed as a kind of self-selecting democracy of artists to avoid this situation.

There were a lot of wonderful stories around hanging shows before an opening. An elaborate dance would be performed while the senior artists decided in which part of the gallery they would or could display their work, and who would hang where. Tantrums would erupt over the prime spaces.

QM: I have got to say that Leo never suffered from that.

JC: No, he was very accommodating but with one or two others there would almost inevitably be some kind of spat.

QM: Usually between Frank Gross and Rudi Gopas. If one of Rudi's star ex-pupils, perhaps Philip Clairmont, was showing, he would make sure that he was put in a good position, even if it meant he had to move someone else's work.

JC: It was always richly fascinating and I still think that they were extraordinarily important. Not only for developments in Canterbury art but as a contemporary art forum for the entire country.

QM: In the end though, I remember them being relieved in some respects that The Group was winding up because I think they were finding it difficult to maintain progress.

JC: I think Leo had something to do with that—he was a pragmatic man and a good businessman as well. He discerned that The Group idea was playing out. It had lasted almost forty years, but increasingly artists were saving their work for one-person shows at the dealer galleries that were springing up through the country. Even the highly respected Russell Clark only had his first one-man show at the CSA in 1957. I was astonished to find that was his first one-man show at around sixty years old.

QM: In Christchurch, the CSA was beginning to represent and promote individual artists. And the Brooke Gifford Gallery had opened two years before...

JC: The senior artists tended to get into other venues. Bill was showing some big works up in the Academy. Leo, who was a good friend of Barbara Brooke's, one of the owners of the Brooke Gifford Gallery, probably talked him into his first show there. It was a most successful show. It meant though that some of those people who had produced about five or six paintings a year had to really get down to it and produce more work if they planned a one-person exhibition.

JH: As painters yourselves, what do you think of him as an artist?

QM: When I remember his work in The Group I think I personally regarded it as being fairly strict and almost primitive. I didn't until years later realise that there were undertones of symbolism and surrealism in it, but it took me quite a while to get used to it. Everyone had a distinct handwriting to their work; Leo certainly did.

As Bill Sutton said, you didn't need to see a signature on a Leo Bensemann to know it. Years later I discovered that Leo had made his name as a portraitist—he was remarkably fast apparently at painting a portrait, but he would get the initial likeness and then give it the Bensemann stamp.

JC: He put a little bit of himself into the portrait. And he could actually paint women, which Bill Sutton said he, Bill, couldn't do. Look at Leo's portrait of Rita Angus, a work of tremendous presence, absolutely marvellous.

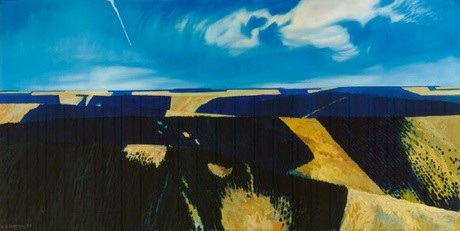

I struggled sometimes with his landscapes, but then I struggled with other landscapes that I wasn't sure about. His were so out of left field that they were difficult to cope with—he made the mist over the Takaka Hills look like a tablecloth and he would make strange quirky things. He was a singular person with an original vision that demanded long, hard looking.

QM: That is exactly what I felt, admired or was intrigued by. Even if you couldn't quite get on the same wavelength you respected the individuality of his vision, which stemmed from and grew entirely out of the core of his being.

There was one aspect about Leo's painting that was interesting: he would listen to criticism about his work, but he had not the slightest intention to change. He never let a work out of his studio until he thought it was totally complete. Whenever we dealt with him at the Brooke Gifford Gallery, he would make sure that everything was varnished within an inch of its life so that it met his standards. On very rare occasions he would take a painting away, do something to it, and bring it back.

Some of the symbolism in the later works used to baffle me a bit, but then as I got to know more about his background after his death I began to see a lot more in it. Actually, later I used to enjoy going out to see the works in Parnell. There was a little gallery there that would show work by some of the older generation painters and they would acquire the odd Leo. They still looked pretty good.

John Coley is an artist and former director of the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch. Quentin MacFarlane is a marine and modernist artist. They were interviewed by Jenny Harper in Auckland on 22 December 2010.