Frances Hodgkins - Belgian refugees

Frances Hodgkins - Belgian refugees

An introduction to Frances Hodgkins's Belgian refugees (1916), narrated by New Zealand actor Sam Neill.

Related reading: Treasury: a generous legacy

Collection

Frances Hodgkins Unshatterable (Belgian Refugees)

The Dunedin-born Frances Hodgkins was running her own watercolour painting school in Paris when World War I broke out in 1914. She relocated to St. Ives in Cornwall, where she found many displaced Belgian families also living, and painted this work in response to their wretched plight. Unshatterable, one of her first oil paintings, was exhibited in London in 1916 and purchased by the painter Sir Cedric Morris. Dr Rodney Wilson, the Gallery’s director in 1980, visited Morris, and with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund, a British art charity, successfully secured this work for the Christchurch collection.

(Treasury: A Generous Legacy, 18 December 2015 – 27 November 2016)

Notes

Study (Woman in a wide black hat) by Raymond McIntyre

This article first appeared as 'The Muse' in The Press on 25 August 2015.

Notes

Still life with flowers in a basket by Pieter Hardimé

This article first appeared as 'Allegory of life's beauty, brevity and fragility' in The Press on 15 August 2014.

Notes

Untitled by Meindert Hobbema

This article first appeared as 'Dutch treat' in The Press on 12 April 2013.

Notes

Angels and Aristocrats

Blair Jackson and I attended the opening of Angels & Aristocrats at Dunedin Public Art Gallery on Friday 27 April. It's spectacular.

Notes

Taking Stock

It's hard to believe, but only eighteen collection works were damaged as a result of all earthquakes, with fourteen damaged on the 22 February 2011.

Notes

Belgian Refugees by Frances Hodgkins

This article first appeared in The Press on 28 February 2007

Belgian Refugees is one of the first oil paintings that Frances Hodgkins ever exhibited, although at the time she was already well accustomed to showing her watercolours. Working in oils and tempera on canvas, she used an experimental technique in this work that gained much from her experience with watercolour. Believed to have been first shown as Unshatterable, in October 1916 at the International Society's Autumn Exhibition in London, the choice of title would suggest a greater sense of resilience than is actually conveyed by this family group. Here only the baby is oblivious to trouble, while his nursing mother seems devoid of expression, and the older children tense with anxiety or fear. Behind the group, a gap in the swirling grey suggests the fact of a missing father, and this steam and smoke speaks of displacement, the atmospheric backdrop of a train station or the symbolic clouds of war. Within the wall of monochrome, intense colour is reserved for mother and child, who also remind of one of Hodgkins' favourite early choices of subject matter in watercolour.

Article

Trove

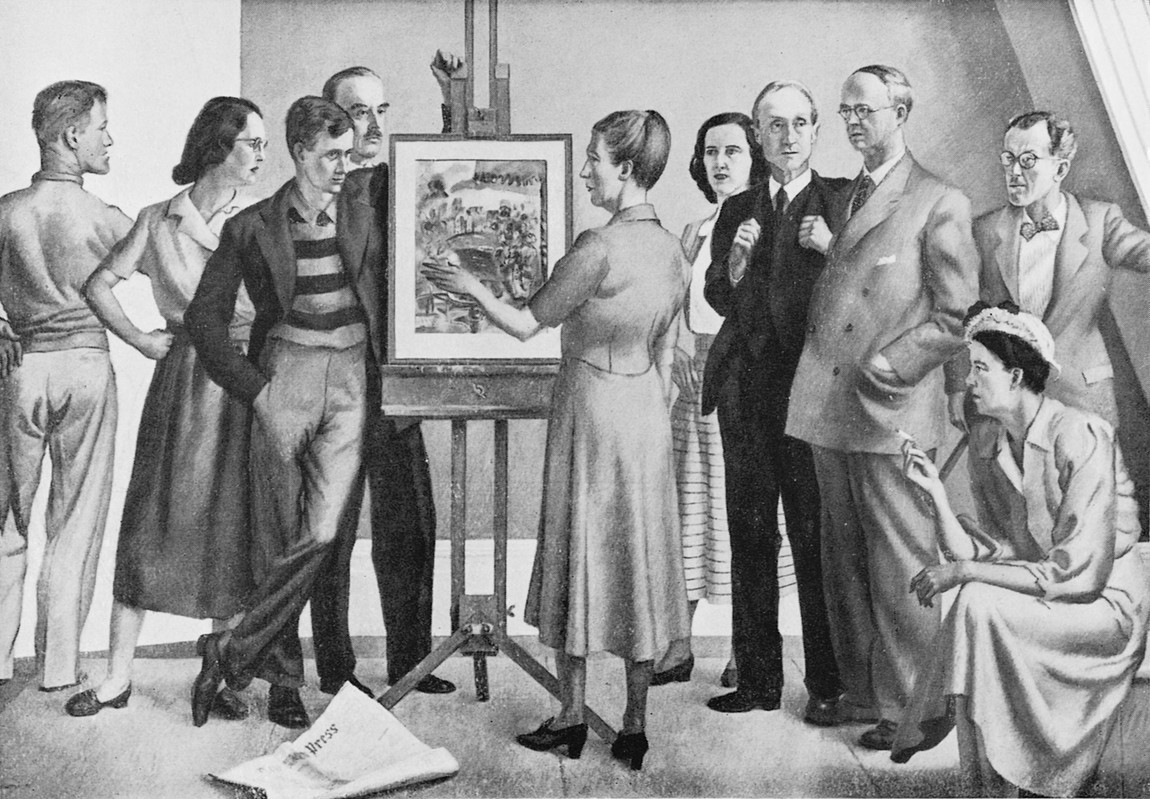

Recounting the untold stories behind some of the works in the exhibition Treasury: A Generous Legacy, curator Ken Hall also underlines the value of art philanthropy.

Commentary

The wisdom of crowds

In recent years, crowdfunding and crowdsourcing have become big news in the arts. By providing a funding model that enables would-be-investors to become involved in the production of new works, they have altered traditional models of patronage. Musicians, designers, dancers and visual artists are inviting the public to finance their projects via the internet. The public are also being asked to provide wealth in the form of cultural capital through crowdsourcing projects. The Gallery has been involved in two online crowdfunding ventures – a project with a public art focus around our 10th birthday celebrations, and the purchase of a major sculpture for the city. But, although these projects have been made possible by the internet, the concept behind the funding model is certainly not new. The rise of online crowdfunding platforms also raises important questions about the role of the state in the funding and generation of artwork, and the democratisation of tastemaking. How are models of supply and demand affected? Does the freedom from more traditional funding models allow greater innovation? Do 'serious' artists even ask for money? It's a big topic, and one that is undoubtedly shaping up in PhD theses around the world already. Bulletin asked a few commentators for their thoughts on the matter.

Article

The East India Company man: Brigadier-General Alexander Walker

Getting to know people can take time. While preparing for a future exhibition of early portraits from the collection, I'm becoming acquainted with Alexander Walker, and finding him a rewarding subject. Painted in 1819 by the leading Scottish portraitist of his day, Sir Henry Raeburn, Walker's portrait is wrought with Raeburn's characteristic blend of painterly vigour and attentive care and conveys the impression of a well-captured likeness.