He Kapuka Oneone – A Handful of Soil

Bill Sutton Hills and Plains, Waikari 1956. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1989

Our expansive collection exhibition explores the fundamental role whenua plays in the visual language and identity of Aotearoa New Zealand. Acknowledging Māori as takata whenua, the first peoples to call this land home, themes of kaitiakitaka, colonisation, environmentalism, land use, migration, identity and belonging are considered through collection works, new acquisitions and exciting commissions. Painting, sculpture, ceramics, photography, moving image, printmaking and weaving by historical and contemporary artists are brought together to reveal how land has been a material and subject for art in Aotearoa for hundreds of years. Here, the Gallery’s curators each take a closer look at a key work from the exhibition that tells us something about our complex relationship with the whenua.

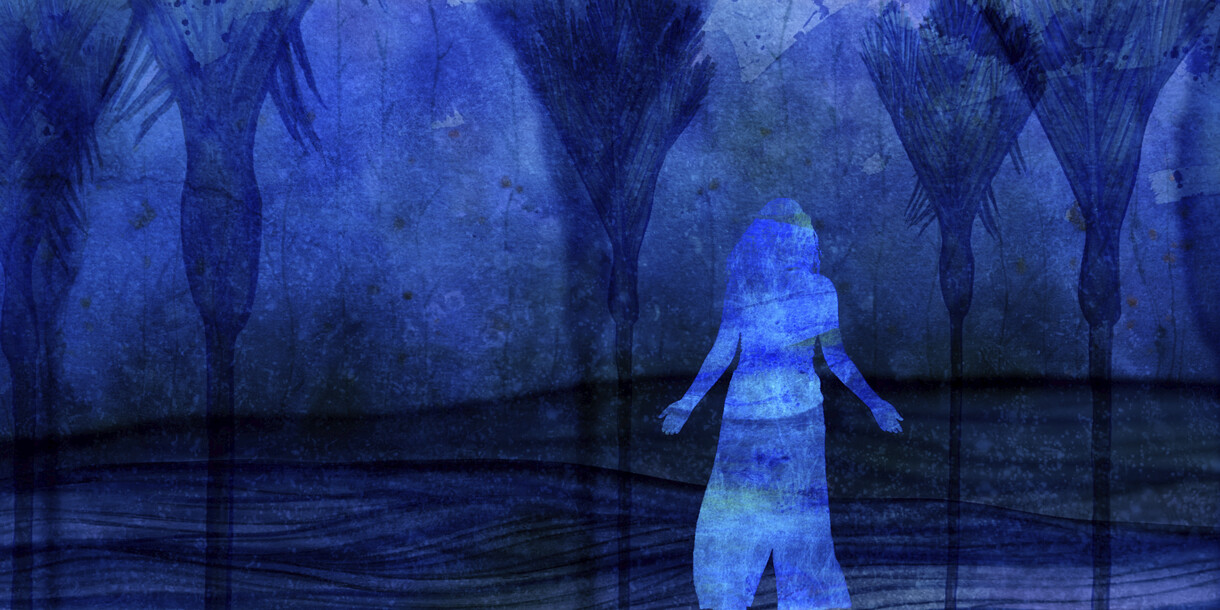

Te Au

Simon Kaan Te Au 2023. Ink and oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2023

Many of the works in He Kapuka Oneone – A Handful of Soil call our thoughts to locations that echo with complex histories. Simon Kaan (Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu – Kāti Irakehu, Kāti Mako ki Wairewa) is interested in the possibility of opening up new places – expansive zones that allow room for imagination and reflection. The space he has created in the recently acquired painting Te Au (2023) is as much atmosphere as place, and draws on ideas from his Kāi Tahu and Chinese whakapapa. The luminous canvas is filled by a vast blue presence – te marama, the moon. Much larger than the tiny waka in the foreground, its scale is suggestive of its influence over the oceans, and all beings on earth. The Māramataka is the Māori lunar calendar, which has long directed activities such as planting, harvesting and kai sharing in accordance with the moon’s cycles. It can refer to light, but also enlightenment: insight, significance and understanding.

The picture plane of Te Au accommodates numerous, contradictory horizon lines that cut across the moon, pulling our gaze in and out as though shifting with the swell and ebb of the tide. Multiple perspectives are a feature of much customary Chinese painting, accommodating the requirements of the artist’s chosen subject rather than conforming to the single, imposed perspective that has dominated much Western art since the Italian Renaissance.

Kaan was born in the coastal suburb of Sawyer’s Bay, near Kōpūtai Port Chalmers on the western shore of Otago Harbour. A keen surfer, he paints watery environments with an intimacy born of close experience, suggesting how their fluctuations might connect with or mirror internal psychological and emotional states. ‘Au’ means many things in te reo Māori, including ‘ocean’, ‘cloud’ and ‘cord’. Kaan has described the delicately traced waka, or ‘wingtip’, that appears throughout his paintings and prints as a symbol of himself or of others. In this context, as writer Bridget Reweti has observed, his title might also lead us to the wake, or ‘au’, we leave behind us when we travel across oceans and through our lives.

Felicity Milburn

Lead curator

Whakapapa – genealogy, lineage, ancestry

Waka – canoe

Kai – food

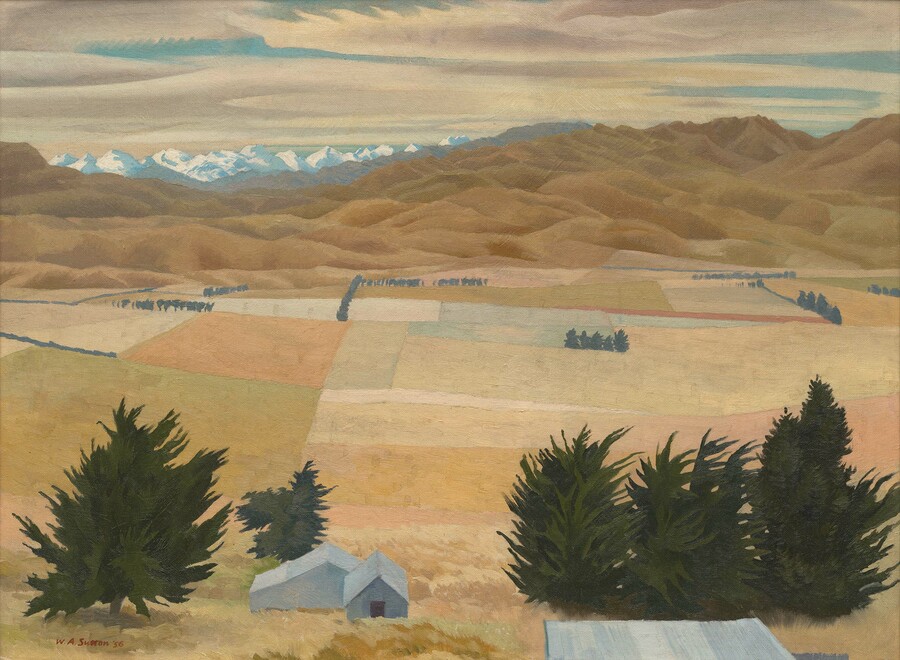

Hills and Plains, Waikari

Bill Sutton Hills and Plains, Waikari 1956. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1989

Bill Sutton owned several motorcycles over the years, including a Matchless and a BSA Golden Flash, and these gave him the freedom to get out of Ōtautahi Christchurch and explore the Waitaha Canterbury back country in search of suitable landscapes to paint.

Waikari was a favoured spot for Sutton, and the back of this stunning painting is inscribed ‘Painted behind Waikari’. The view is taken from Oxford Street, behind the site of the town’s old Great Northern Hotel on the road leading further inland towards Hawarden. The Gallery also owns his painting of the nearby Māori rock art site at the Weka Pass Historic Reserve.

This sweeping view looks out over the patchwork paddocks of the wide plains to the sun-browned foothills and, behind them, the snow-covered mountains of Kā Tiritiri-o-te-Moana Southern Alps. He sets this landscape off under a classic Waitaha nor’west sky, where the hot dry föhn wind can blow relentlessly over the land and creates spectacular cloud formations.

Residents and visitors to Waitaha either love or loathe these fierce nor’westers. They can get under your skin, especially if they blow for a couple of days. Sutton loved them, and his archives hold numerous cloud photographs that he took to inform his paintings. He felt a deep connection to the Waitaha landscape and particularly its skies:

… because of the föhn winds which come from Australia and behave rather unkindly on the West Coast and then come over to Canterbury and behave much more beneficently over us, blowing hot air which I enjoy enormously. And the clouds which accompany these pleasant physical processes are enchanting in shape. Long lens-shaped cumulus clouds, which always fascinate me because there’s so much freedom of construction among them although they belong to a specific family. I can parallel or relate these shapes to land shapes to shadow shapes, so that it’s a splendid motif to seize upon – the shape of the cloud – and echo it through the whole landscape.

The prickly, dark green macrocarpa trees and steely edged farm sheds stand out in stark contrast to the more muted softness of the landscape in Hills and Plains, Waikari. Sutton’s focus on the line of hills on the horizon highlights his belief about the wide landscapes of Waitaha, where “… you don’t look up and down but from side to side”. I’m sure that after making his studies for this painting in the hot sun he enjoyed a glass or two of cold draught beer whilst looking at the landscape from the front bar of the Great Northern Hotel.

Peter Vangioni

Curator

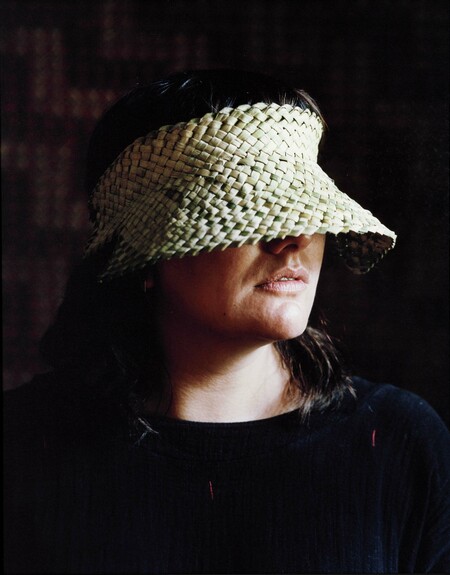

Travel Without Moving

Conor Clarke Travel Without Moving 2018. Digital print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2023

Travel Without Moving was made by photographer Conor Clarke (Kāi Tahu) while on residency in Whanganui, and depicts a Māori tradition of shielding one’s eyes when passing significant mountains. Within te ao Māori, mountains are living ancestors; out of respect, some people use a string of leaves or a woven object to cover their eyes and avoid the temptation of looking up at the peak. In this case, a harakeke visor provides a shield for the wearer.

This perspective of the world, grounded in whakapapa and an understanding of the deeply interconnected relationships of Māori with the whenua, mauka and awa, is in contrast to a European view of humans as distinct from the environment. The emergence of British landscape painting in the nineteenth century was based on the Victorian belief that nature was God on earth, and was a reaction to the urbanisation of the population and industrial revolution. Works of this period are infused with nostalgia for nature, at times emphasising the sublime power and beauty of the natural environment.

Early colonial landscape painting in Aotearoa New Zealand draws on this established artistic tradition. Although works sometimes capture the hardships encountered when attempting to settle in this new land, more often they are topographical renderings intended to accurately survey the features of the land that colonial settlers were trying to conquer, acquire and prosper from. As artist Charles Blomfield wrote:

Never before has there been a nobler opportunity afforded the artist to aid in the growth of his native land, and to feel that, while ministering to his own love of the sublime and beautiful, he was at the same time a teacher and co-worker with the pioneer, the man of science, and the soldier, who cleared, surveyed and held this mighty continent and brought it under the mild sway of civilisation.1

Instead of a narrative based on human domination over the land, Clarke’s photograph represents a starkly different way of understanding our relationship with the environment – seeing ourselves as part of the land, derived from and responsible to the mauka, awa and whenua we live with. As it becomes more evident that our impact on the environment has led to overwhelming damage, deforestation, species loss and climate change, this sense of respect and honouring of the land is imperative for our future.

Melanie Oliver

Curator

Harakeke – Phormium tenax, or New Zealand flax, an evergreen perennial plant native to Aotearoa

Whakapapa – genealogy, lineage, ancestry

Whenua – land

Mauka – mountain

Awa – river

Twilight Vessel

Tracy Keith Twilight Vessel 2021. Raku fired ceramic. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2023

… to capture the deep rawness and movement of uku, where material informs practice and the raku process defines the outcome, where vessels look as if they were pulled from the earth.2

Ngāpuhi ceramicist Tracy Keith’s works are shaped and moulded by hand, and the unusual, richly textured surfaces of his vessels contain the imprints of unknown, imagined forms – moa, fish bones or seaweed perhaps – that might have been unearthed from a midden or the bottom of the moana.

Keith grew up in Tokoroa, against the backdrop of the Kinleith pulp and paper mill. With this in mind, there is an industrial, almost dystopian feel to his work.3 While the mill provides hundreds of jobs, as Keith explains it also requires the movement of workers, often Māori, from their tūrakawaewae, fuelling a growing disconnect between people and the whenua. He writes: “When we follow work in industries like paper mills, smelters and freezing works it means we can’t always live by our tūrangawaewae … and this can lead to the deterioration of culture.”4 There is tension, too, between the economic benefits of these industries for small towns, and the impact of their activity on the health of the environment.

Keith fires his vessels using the Raku method – an ancient Japanese practice that involves heating glazed ceramics to high temperatures very quickly, and then removing them from the kiln while still hot. They are then cooled rapidly, either in the open air or by immersing them in a combustible material such as straw or paper. This cooling process results in unexpected colours and textures, and Raku fired ceramics are unusual because the final outcome is unknown even to the maker.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, Keith continues a whakapapa of contemporary Māori clay practices. In the 1980s a group of Māori clay artists emerged out of Ngā Puna Waihanga, the Māori Artists and Writers Association. Ngā Kaihanga Uku held their first hui in Tokomaru Bay in 1987. The principal founding members were Baye Riddell (Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau a Ruataupere), Manos Nathan (1948–2015, Ngāti Whātua, Ngāpuhi, Crete), Colleen Waata Urlich (1939–2015, Te Popoto o Ngāpuhi ki Kaipara, Te Rarawa), Wi Taepa (Te Arawa, Ngāti Whakaue, Te Ātiawa) and Paerau Corneal (Ngāti Uenuku ki Manganui a te Ao, Ngāti Tūwharetoa). Collectively, works by these artists acknowledge the rich history of uku within te ao Māori as seen in pūrākau, whakapapa and taoka. Tracy Keith continues their legacy, reaching back through the history of uku and whenua in order to explore contemporary realities of dislocation and connection for Māori.

Chloe Cull

Pouarataki curator Māori

Ngāpuhi – tribal group of much of Te Tai Tokerau Northland

Moana – sea, ocean

Tūrakawaewae – place where one has rights of residence and belonging through kinship and ancestry

Whakapapa – genealogy, lineage, ancestry

Uku – clay

Te ao Māori – the Māori world

Pūrākau – myth, ancient legend, story

Taoka – treasures, things of cultural value

Whenua – land

Mount Cook & Francis Joseph [Franz Josef] Glacier, New Zealand

![William Fox Mount Cook & Francis Joseph [Franz Josef] Glacier, New Zealand – from Freshwater Creek distance about 40 miles 1872. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1971](/media/cache/42/c4/42c4fbbc23c07154bcf1bbd7c7dce627.jpg)

William Fox Mount Cook & Francis Joseph [Franz Josef] Glacier, New Zealand – from Freshwater Creek distance about 40 miles 1872. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1971

In March 1872, during his third term as colonial premier, William Fox visited Te Tai Poutini West Coast and journeyed south from Hokitika to Ōkārito and the glaciers, travelling primarily on horseback and on foot across steep terrain. Fox’s small travelling party comprised his wife Sarah, his private secretary Mr Brown, chief surveyor of Westland Gerhard Mueller, and other local officials. At least one watercolour sketch made during the nine-day trip suggests they were joined by representatives from local iwi.5 was detailed in several newspaper reports. On 9 March, the party reached the glacier Te Moeka-o-Tuawe, which was renamed after Fox by others in his party. Two days later, he admired a large goldmining water race at Five Mile Beach before heading back towards Hokitika. On 12 March, the party stayed one night at Saltwater Lagoon, north of Whataroa River, which is believed to be the setting for this watercolour painting. In the foreground, cattle graze in cleared land by a modest dwelling and a mirror-like body of water; behind, a dense swathe of bush and kahikatea forest rises to the towering Aoraki Mount Cook and Kā Roimata-a-Hinehukatere (Franz Josef Glacier).

Six months later, Fox delivered a scientific presentation on glaciers at the Colonial Museum in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, accompanied by an exhibition of his recent watercolour paintings. Alongside his Te Tai Poutini works were “a large number of sketches illustrative of the scenery which Mr Fox had witnessed during his travels in Switzerland”.6 The event was held inside the Māori House, Te Hau ki Tūranga – an ornately carved whare whakairo that was stolen from its Rongowhakaata owners five years prior by Minister of Native Affairs (and fellow artist) James Crowe Richmond, in punishment for resisting the colonial government in the Aotearoa New Zealand land wars.

Although “admired as much for the grandeur of the scenery depicted as for the excellence of the sketching”, Fox’s watercolours also received mild criticism, in that he “made no attempt to treat the subject which he had taken in hand – the glacier formation – in a professional or scientific manner, but merely from what might be termed a picturesque point of view”.

Ken Hall

Curator

Whare whakairo – carved meeting house

Rongowhakaata – tribal group of much of Tairāwhiti Gisborne