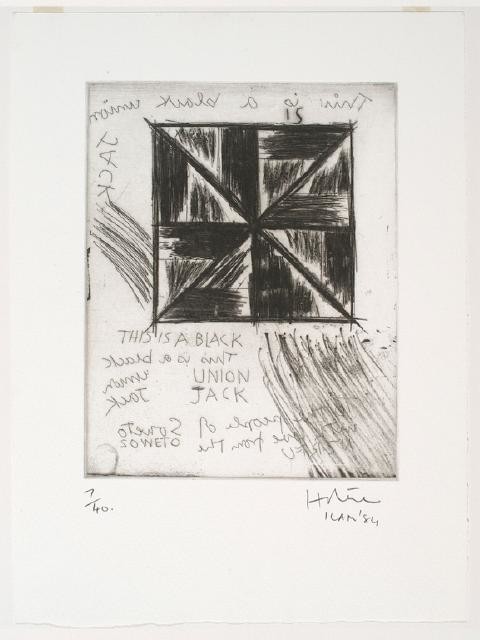

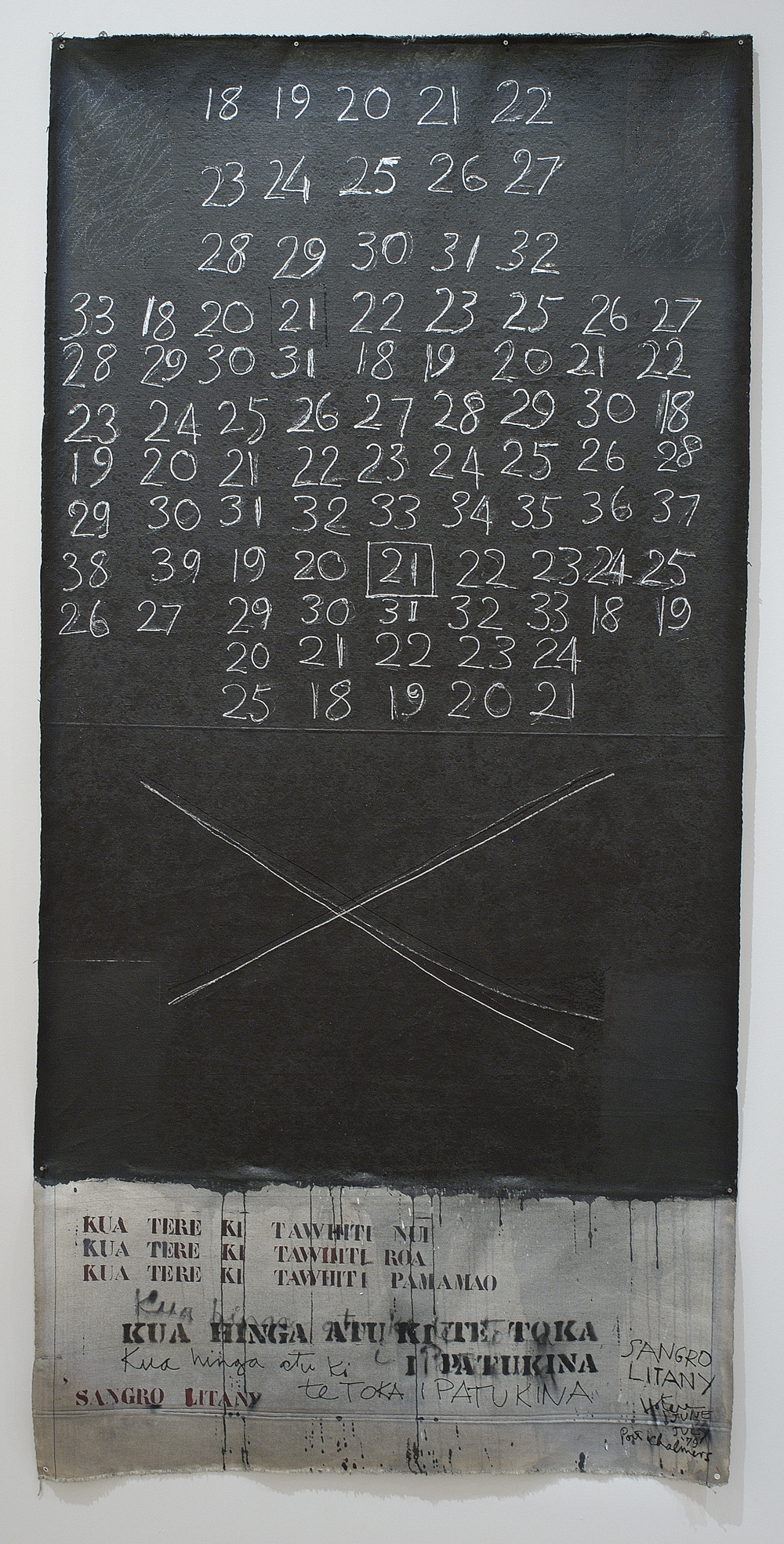

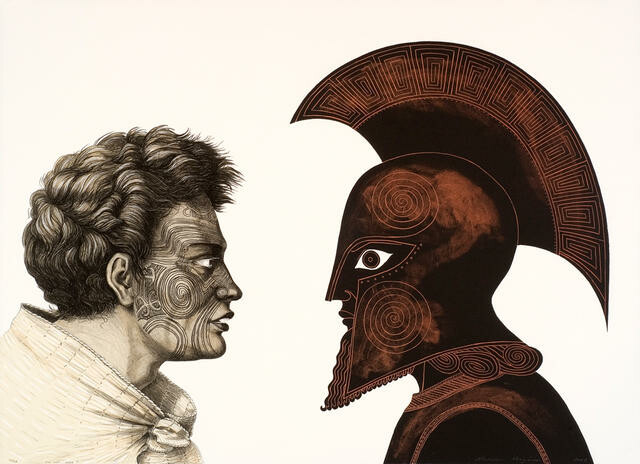

Ralph Hotere: Ātete (to resist)

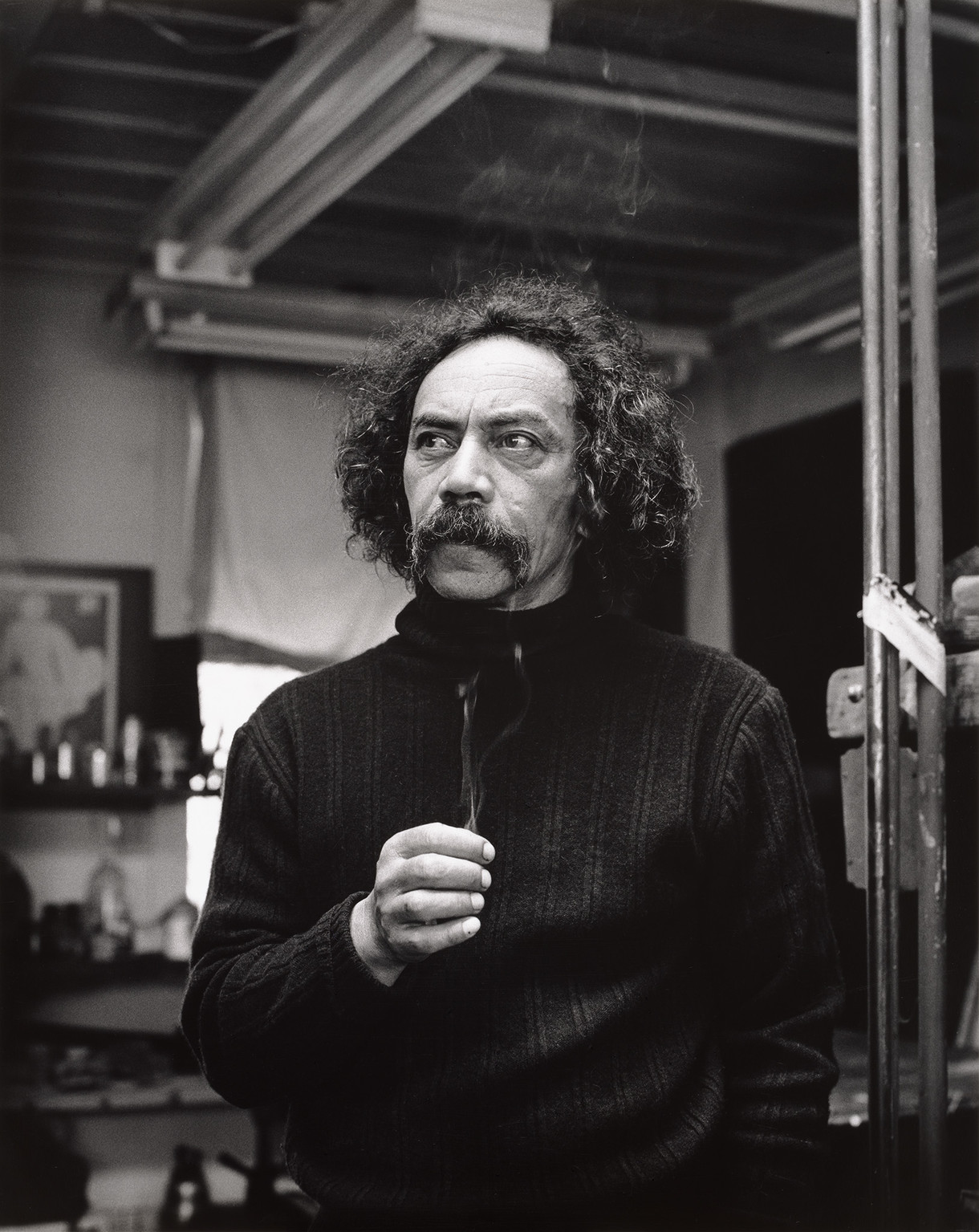

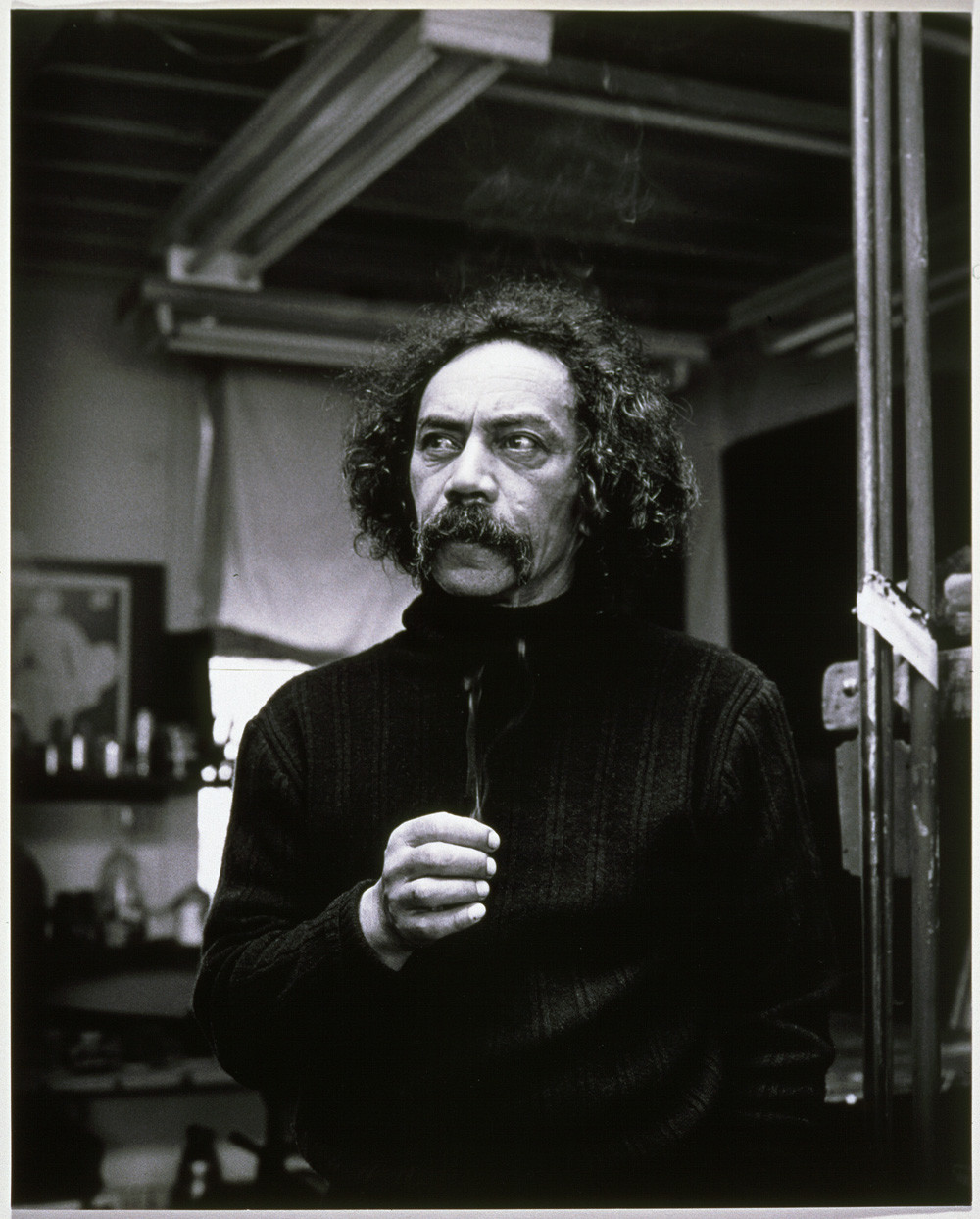

Robin Morrison Ralph Hotere 1992. Photograph. Courtesy of the Robin Morrison Estate and Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum.

Ralph Hotere’s art charted his journeys throughout Aotearoa and the world, reflecting on his experiences, identity and politics. As the first major survey exhibition of Hotere’s artistic career for over twenty years, Ātete celebrates his achievements and brings his vision to a new generation. It’s been a huge project to bring together so we thought it was timely to ask the four curators to tell us a little about their relationship with Hotere – how do they connect as individuals with the artist’s works, and the themes and the locations that they explore?

HUSTLED NOTES ON CONNECTEDNESS

Nathan Pōhio

Ralph Hotere’s studio at Observation Point, above Kōpūtai Port Chalmers,1 fell into the takiwā of Te Rūnaka o Ōtākou. Many of Hotere’s artworks speak to me of the whenua (land) and tīpuna (ancestors) I whakapapa to, generating a great swirl of cultural and personal reference bound by the artist’s presence in Kōpūtai.

Hotere lived and worked in Kōpūtai from 1971 until his passing in 2013; his output was prolific and the local whenua and manu (birds) are consistent features of his practice, as are national and international politics. The flight paths of kuaka appear, as if to link his home to his tīpuna and whānau residing in the north and Mitimiti – and perhaps arguably back to Europe.2 Their migrations are highlighted by karakia (prayer) and whakataukī (proverbs) in his work, suggesting these migrating manu warmed his heart on their return.

Seen from his studio above Kōpūtai, Aramoana was to Hotere’s left and Pukekura Taiaroa Heads to his right. Both are significant sites for the people of Ōtākou, who were sheltered there from easterly winds by Pukekura.

Aramoana encapsulates a span of artistic triumphs as demonstrated by Aramoana Pathway to the Sea (1991), the collaboration with Bill Culbert arguably being the ariki or supreme piece. The place names Taiaroa Heads and Aramoana appear in Hotere and Culbert’s series of lithographic works Pathway to the Sea – Aramoana (1991).

As a lament for Parihaka, works like Comet over Taranaki and Parihaka (c. 1972) from Hotere’s Te Whiti series are intimate, whisperings of paintings that haunt the memory. Combined, these works act like a kind of essay and tangi for Te Whiti-o-Rongomai, Tohu Kākahi and the thousands of people of Parihaka. I also see links between whānau from Rēkohu the Chatham Islands and Parihaka, as most iwi and hapū sent food in support, and I recognise the toroa feather as a symbol of peace for Parihaka that also relates to Moriori custom.

As children in Rāpaki and Whakaraupō Lyttelton, we were banned from parts of the urupā where unmarked graves belonged to men from Parihaka who had died in Dunedin Prison. Their bodies were brought to Rāpaki to provide the kawa, tikanga and sanctity of an urupā. Descendants of Parihaka visit Rāpaki annually to tangi their tīpuna – the marae calendar is blocked out for those visits.

These just are a few examples of the resonances I find in Hotere’s work, they contain deep meaning for Māori in the south and no doubt more still for Māori in the north.

SMALL ACTS OF RESISTANCE

Lucy Hammonds

The bombing of the Rainbow Warrior at Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland’s Marsden Wharf on 10 July 1985 resulted in the death of photographer Fernando Pereira, and left Aotearoa reeling. Few in our country could comprehend this act of aggression by the French authorities in retaliation to protests against French nuclear weapons testing in the South Pacific. The attack galvanised the nation, spurring protest across the country and ultimately leading to the creation of the 1987 New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act.

I was raised in a family that participated in the protest campaigns of the mid-1980s. My childhood memories are of mucking around in the bush with other kids, while our parents attended peace group; of Greenpeace T-shirts and gatherings; and of photographs of friends’ boats flying protest flags in the Hauraki Gulf. I remember walking across the terracotta tiles of Auckland Art Gallery, cool and quiet, and looking into the searing red centres of Ralph Hotere’s paintings protesting the devastation being meted out onto the Pacific atoll of Mururoa. Thirty-five years later, and in Ātete I’m greeted again by Dawn/Water Poem, sitting alongside works that bear witness to the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior and her subsequent scuttling at Matauri Bay.

The enduring power of the politics of Hotere’s works was one of the most important aspects of our development of Ātete. Throughout the exhibition we are reminded of acts of violence and injustice that have been perpetrated against both people and place. Yet in parallel, we are presented with a view of how art can lead us to stand strong in opposition – E Tū, Kia Ātete.

FLIGHT PATH TO RALPH’S OPENING IN DUNEDIN, SPRING 2020

Peter Vangioni

Taking off to the north we soon turn south over the Waimakariri River – the harbours and bays of Horomaka Banks Peninsula sparkling in the morning sun below. Te Waihora and the mighty rivers of the Canterbury Plains act as markers for the journey south to Ralph’s opening at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. I plot my own course via the Rakaia / the Rangitata / the Waitaki into Otago and Shag Point / Taiaroa Head / Aramoana / Ōtākou / Hereweka and there in the distance, the white sands of Allans Beach. Closer, just below lies Kōpūtai Port Chalmers with its massive container cranes, blue now but lime green when I was a kid. And beyond them, the remnants of the battered and bruised headland of Observation Point and the house where my great aunt Nancy Simpson lived from the 1930s until 2012.

The view from Nancy’s verandah looked right out over Back Beach and across the harbour towards Portobello Bay. It is a place that, like many in my extended family, I hold dear to my heart – a warm house of laughter, plenty to eat and drink and endless games of canasta played into the small hours. Perched right on the corner of Scotia and Constitution streets just below where Ralph worked for much of his career, Nancy saw the artist come and go from his first studio on Aurora Terrace in 1971 and then his second studio further up past the Flagstaff in the old stables that once belonged to the historic Willowbank house.

Nancy didn’t really get contemporary art – she was more a fan of George Chance’s pictorial photographs than Ralph’s modern abstraction. But she was certainly one of those Dunedin locals Ralph famously described as “just accepting me as a painter and [letting] me get on with my work. They don’t do that in Auckland.”3 She wasn’t one to bother the artist… except once. This was when Ralph had the burnt-out hull of the trawler Poitrel delivered to the street in front of his Aurora Terrace studio in 1984. On this occasion she knocked on Ralph’s studio door to get to the bottom of the matter. Questions were asked… “What’s the Poitrel doing here on the street?” “You’re going to turn it into an artwork?” “How long will that take?” Ralph no doubt charmed her and she accepted, as did the majority of the community, that the boat was now part of his practice and therefore a fixture in the area. The Poitrel’s reincarnation as Black Phoenix (1984–88) is one of Ralph’s greatest achievements and for me being able to include it in Ralph Hotere: Ātete (to resist) and see it return to Te Waipounamu has been the absolute highlight of the whole process of co-curating this exhibition with Lucy, Lauren and Nathan.

The only other concern Nancy had regarding her artist neighbour was the speed with which Ralph would drive down Constitution Street and swing into Scotia Street. She would look up from her gardening and watch him whizz past in his ute, waiting for his dog, who was perched on the back, to end up in her front garden. He never did.

On our regular visits to Nancy throughout the 1990s and 2000s we had many discussions around the cutting off of Observation Point. In March 1993 Port Otago Ltd gained planning tribunal approval for its proposed excavations on the point. Nancy felt strongly that Port Chalmers was a working port (her father was a boiler maker) and sacrifices such as cutting away the land at Observation Point had to be made to create jobs for the community. This view was very much at odds with Ralph’s opinion. When they finally did make the cut into the point in 1994 it certainly was brutal – even Nancy could see that. The wet, grey clay exposed by the excavation was not a pretty sight, a gaping sore that was in your face on the drive back to the Port from Aramoana at the time. I think she came to regret the loss, not so much the destruction of Ralph’s studio or Willowbank, but the irreversible change to the landscape. Her beloved view over Back Beach was altered forever. To me, it beggars belief that the cutting remains unstable and in seemingly continual need of stabilising and bandaging with erosion proof cloth twenty-six years later. If she was still around today I suspect Nancy would also not be happy at the way Port Otago Ltd continued to buy up all the houses on the point and promptly demolish them, erasing an important part of her community. But maybe the fact that the Poitrel is still present, standing proudly in the Hotere Sculpture Garden as Black Phoenix II after all these years, would raise a wry smile on her face.

ĀTETE (TO RESIST)

Lauren Gutsell

It seems almost everyone has their own Ralph story – from fleeting chance encounters with the artist, to lifelong friendships, to powerful and memorable moments spent with his work. In both the development phase of Ralph Hotere: Ātete (to resist) and since it has been open to the public, we have been able to share a range of experiences and memories with people from across Aotearoa. In my conversations with visitors to Ātete, Hotere’s works have acted as carriers of personal memory, and of connections to place and particular moments in our national and global history. From those that were, like Hotere, in London in the early-mid 1960s; those who remember being greeted by Godwit/Kuaka (1977) in the arrivals lounge at Auckland International Airport; those who share the trauma of losing a family member in World War Two; to those who were also strident in their protest of the proposed aluminium smelter at Aramoana.

In Ōtepoti Dunedin, the threat of the smelter at Aramoana is a strong memory for those who lived through the proposals and subsequent protests in the 1970s and early 1980s. The proposal was a deeply polarising issue and activated many in the community. Those who were active in their opposition to the smelter included a group of local artists and writers such as Ralph Hotere, Bill Culbert, Cilla McQueen, Marilynn Webb and Brian Turner. When thinking about this time, Gary Blackman’s photograph Aramoana (1980) always comes to mind. Blackman’s work memorialises a direct act of protest – the throwing of black paint across a large ‘pro-smelter’ billboard, leaving it almost illegible. In a letter written on the back of an exhibition flyer that featured this image, Ralph Hotere wrote to his friend Bill Manhire that it was “probably the best painting I’ve done in 30 years. It took me 2 seconds.”4

Ātete has shown me the ways in which Hotere’s work helps connect people to specific memories, places and moments in time, while providing the opportunity to teach, remind and inspire those generations who are coming to the work for the first time.