Where in the World? Placing New Zealand in the Pacific

Tuan Andrew Nguyen The Island (film still) 2017. Colour, 5.1 surround sound; 42 min. Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan Gallery

“It is a strange fact that New Zealand can be literally all at sea in the Pacific Ocean, and yet pay that ocean, and neighbours and relations within it, so little attention.”

— Damon Salesa, Sāmoan historian

“… this small and very British country is producing some honest and lively artists whose eyes open upon a land not at all like England, but whose minds are formed in the living tradition of Western culture.”

— Helen Hitchings, New Zealand gallerist

The Asia-Pacific Century: Part One (installation view), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, 2016

Artists, curators and institutions are engaged in a continual task of placing ourselves. As people whose work is founded on construction and imagining, we are forever building ourselves in relation to each other and to the world through art, exhibitions and text. Finding our context, or placing ourselves socially, politically and geographically thus becomes the main feature of one’s work. And a turbulent one at that, changing over time.

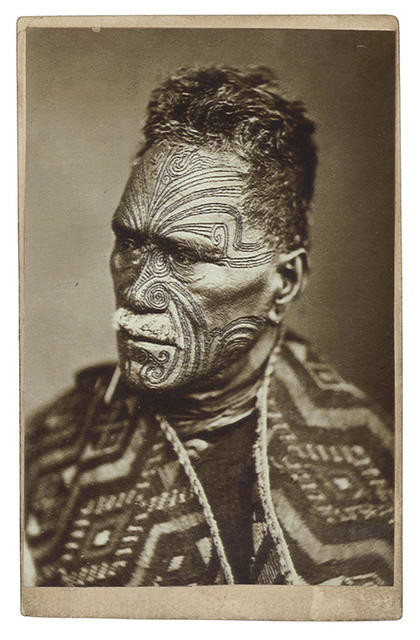

For a long time now, New Zealand under the British crown has held strongly onto its connections to everywhere except its closest neighbours – the Pacific island nations that sit on either side of it. This signals the strength of colonial, economic and political ties to New Zealand, overlooking the part of the world we physically exist within. This overlooking of the Pacific is particularly noticeable in shared histories of the Pacific region that are not centred on New Zealand or the kinds of subjects that are typically foregrounded in New Zealand society and history.1 Those subjects in New Zealand’s history were generally speaking colonial subjects, and that is a sentiment equally visible in New Zealand’s art history.

Mid-century artists such as Louise Henderson, Frances Hodgkins, Len Lye and Gordon Walters were in a constant negotiation between being in or of New Zealand, and yet wanting their art to speak to the movements and aesthetics of Europe or the United States. Theirs was not a settled generation, but a migrant one, who understood ‘home’ to be places such as England or France. In Louise Henderson: From Life, the painter comments, “I am ever so bored in this country – it is so dull. Forgive this – you of course are a cosmopolitan and shall understand what I mean.” To which painter John Weeks replies, “We are so isolated here, so far from contact with all the newer movements that it is easy to dip into a rut. There is so little here in the art world to draw comparison from, and this is not good for the progressive painter.”2 For these migrants, there was a pervasive ‘backwater’ mentality – to get art, and to get good at it, you had to leave New Zealand. It’s something that you might cynically argue still exists today with the annual flocking of art school graduates to Berlin, London and New York.

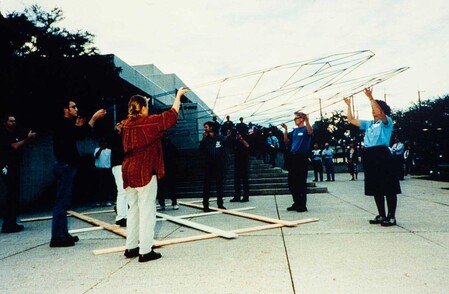

The Asia Pacific Triennial (installation view), Queensland Art Gallery Gallery of Modern Art, 1993

A new idea of regionalism, the Asia Pacific or Pacific Rim, swept through New Zealand’s contemporary art in the 1990s. Coming off the back of regionalism and Māori nationalism, the 1990s ushered in a new way to contextualise ourselves as well as the new political concerns of a post-colonial nature. The geography of the Asia Pacific placed us geographically within the Pacific Ocean, yet still allowed us to connect internationally to art centres in the Americas as well as Asia. The political movement towards a notion of the Asia Pacific was said to have been initiated by the United States; with no connection to Asia yet bordering the Pacific Ocean and with Pacific nations under their colonial control, the conceptualisation of the Asia Pacific gave them a strategic and political relationship to Asia. In art however, the rise of the Asia Pacific arguably came through the establishment of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in 1993. The exhibition today is held between Queensland Art Gallery and the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane and is highly regarded as one of the premier exhibitions in the region. The critique that the APT has received over the years, however, is that it is not actually an exhibition of artists from the Asia Pacific as a whole, but rather of artists from New Zealand, Australia and Asia. This aligns with Tongan and Fijian scholar Epeli Hau‘ofa’s concerns that the Pacific just becomes expendable as simply the “hole in the doughnut”.3

A recent curatorial project (and thought exercise) by curators Ioana Gordon-Smith and Emma Ng titled The Asia-Pacific Century (2016–17) refocused the external notion of the Asia Pacific as a tool for expansion and positioning within global economics and politics, as a way to think about the changing demographics within New Zealand. It is projected that by 2038, New Zealand’s Māori, Asian and Pacific populations will collectively make up 52% of the total population. Predicting that we were in the midst of a shift away from conceiving ourselves as a thoroughly British colony, they proposed “Asia-Pacificness” as a primary condition of New Zealand’s near future – one that requires us to rethink the dynamics of diversity and multiculturalism in relation to our unique bicultural foundations.

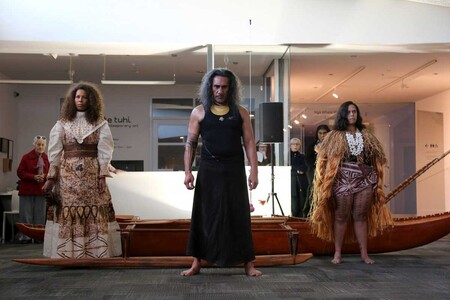

Gordon-Smith’s and Ng’s prediction couldn’t have come any truer. Over 2018 and 2019 we have seen a growing interest in positioning New Zealand and its art within the Pacific and specifically the Pacific Ocean, Oceania or Moana. Exhibitions such as Oceania (Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2018), Seeing Moana Oceania (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2018–19), Two Oceans at Once (ST PAUL St Gallery, 2019) and Moana Don’t Cry (Te Tuhi, 2019) all ask what it means to be of this place. A growing comfort in understanding ourselves as geographically Pacific goes hand in hand with increased mobility through cheaper air travel as well as online – the global world is something we are a part of by default. Seemingly our colonial cringe and our backwater mentality seems to be shifting as we acknowledge the rich histories and epistemologies of this place and as climate disaster introduces an increased sense of urgency upon us.

Ioane Ioane Moana Don’t Cry 2019. Performance ritual by Ioane Ioane, Sila Ioane and Shannon Ioane, costume design by Rosanna Raymond. Performed on 31 August 2019 during the opening of Moana Don’t Cry. Commissioned by Te Tuhi, Auckland. Photo: Amy Weng

Attempts to understand ourselves in relation to the Pacific are perhaps best-known through Auckland’s catch phrase, the largest Pacific city in the world.4 The term was first used in 1966 and was based on the census of that same year.5 However, not only is this fact statistically questionable, it also gives us proximity to a Pacificness without having to care about Pacific people. This attitude was highlighted last year by commentator Heather du Plessis-Allan when she discussed Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s decision to visit the Pacific Islands Forum hosted in Nauru. Speaking on NewstalkZB, Du Plessis-Allan dismissed the visit as a waste of time, referring to Nauru as a “hell hole” and Pacific people as “leeches”, and commenting that the Pacific Islands “don’t matter” because all they want is money from New Zealand.6 The idea that New Zealand is a First World nation which is in the Pacific but not of the Pacific is clear. Understanding our place in the world in this way also makes the economic contributions the Pacific makes to New Zealand – through a hardworking and resilient labour force that fills the roles of the New Zealand economy no one else wanted from the 1950s until today – invisible.

Coming to terms with our place in the Pacific is an exciting thing to be doing politically and artistically. For Pacific and Māori people, the ocean and its creatures make up key parts of one’s personhood, cosmologies and knowledges. From the edge of the ocean it’s easy to cherry-pick what you want and leave behind what you don’t, as Pacific scholar Teresia Teaiwa wrote.7 Let’s hope that seeing ourselves as geographically Pacific helps us to understand our relationship to the region through the uniquely bicultural landscape of Aotearoa New Zealand.