The Seas are Rising: So Are We

Connie Samaras Untitled (Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica) 2005. Single-channel video, colour, sound, duration 4 min 30 sec, looped. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2014

In Te Ao Māori the whakataukī “He toka tū moana” pays homage to the rock that withstands the sea as a metaphor for human strength in our cultural or political beliefs, whatever may come. But while the rock is steadfast, the octopus Te Wheke is a shape-shifter, canny and malleable.

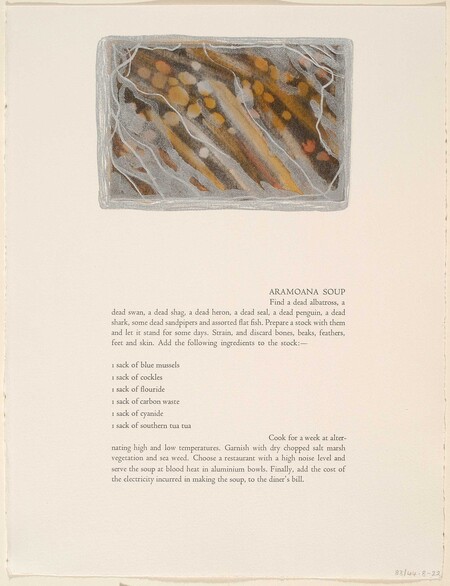

Marilynn Webb Aramoana Soup 1982. Monotype. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1983

The narrative of the epic contest to outwit Te Wheke traverses the fluid continent of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa / the Pacific Ocean. In the late 1960s Te Rangi Hiroa drew an octopus in the form of a map with tentacles outstretched across Polynesia’s islands.1 In one story of Te Wheke and Kupe, the great navigator is stretched to the limit as he tries to quell the giant creature; his pursuit across the seas leads to the discovery of the North island of Aotearoa New Zealand. While Te Wheke appears first as a latent threat with tentacles that would ensnare Kupe’s waka, the octopus rises to become an oceanic symbol by which to remember the geopolitical origins of Pacific migrations. The octopus is both vulnerable and resilient. These twin concepts coalesce in the contemporary artworks featured in the exhibition Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania. The exhibition situates Ōtautahi Christchurch as a connective point within a vast liquid continent – conjoining artworks from many islands including Japan, Indonesia, Samoa, the Cook Islands and Aotearoa.

Many of the artists featured in Te Wheke use sculptural materials and video images to call attention to the unpaid legacy of a changing climate left to the biota of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. In the Samoan phrase fesuia’iga o le tau (climate change) Albert Refiti finds an active engagement with, and preparation for, current and future climates,2 rather than a passive acceptance of things as they are. Cycles of drought and cyclonic events have always been anticipated by the long-term preservation of food for times of hardship in Samoa. Rather than an imminent threat, the ocean flows in co-relation with the land, always in formation. Today, the youth activist group Pacific Climate Warriors acts in readiness for a changing climate to confront the inertia of many politicians. On 27 September 2019 in the school climate march in Tāmaki Makarau Auckland, climate warriors of many different islands led the chant for the thousands gathered; “The seas are rising, So Are We!” Such concerted acts offer hope that demands for change, if voiced strongly enough might cause planetary stakeholders to pause. The tentacles of togetherness reach across the false geopolitical divides established between Moana peoples by Imperial forces, as Lana Lopesi has compellingly described.3 Artists also rise to the challenge of mediating between governments, multinational interests, science and communities in the struggle for climate justice and indigenous rights.

Te Wheke reveals an ocean that can no longer be imagined as a limitless resource for humanity alone. Late last century, the painter Ralph Hotere joined environmentalists in protesting the nuclear assaults on the Pacific, first by the Americans (in the benignly named Pacific Proving Grounds) and later with French nuclear testing in Mururoa Atoll. Traces of radioactive contamination still leak into the islands and waters of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. In a sea closer to home, Hotere also joined the decade-long campaign of artists and citizen activists against a proposed aluminium smelter at Aramoana, at the northern side of Otago harbour in the 1980s. Works in this exhibition by Marilynn Webb and Hotere were made in resistance to the potentially disastrous scheme for the marine environment. Webb’s text-based monotype Aramoana Soup (1982), a work she created soon after the declaration of the “Independent State of Aramoana”, riffs on the phrase “recipe for disaster”. The toxic soup’s ingredients are listed: “1 sack of blue mussels, 1 sack of cockles, 1 sack of flouride, 1 sack of carbon waste, 1 sack of cyanide, 1 sack of southern tua tua” to be served “at blood heat in aluminium bowls”. While in Hotere’s Aramoana – Drawing for a Black Window (1981), a ghostly night view of the fragile coastal topology at the mouth of Otago Harbour is traced in white paint. Across the windowpane the word ‘Aramoana’ is written backwards and underlined – perhaps speaking directly to the external neo-Imperialist forces on the other side of the window. An official sign declaring the proposed aluminium smelter is photocopied and collaged onto the drawing, scrawled out with an X. The X in Hotere’s visual language is a sign of deletion that is “all cancelling and all-refusing” as Francis Pound once wrote.4 From this unwanted found-object bursts a waterfall of silver ink and scrawled graphite, prophesising the toxic tailings that would spill into the ocean. In a hopeful moment for our contemporary environmental struggles, their protest defeated the plans for the smelter.

Joe Sheehan Mother 2008. Greywacke stone. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2008

In other artworks in Te Wheke new life emerges also from recovered materials. In Rozana Lee’s Adzan (2018), a video is projected onto a fabric sheet saturated by water from the Indonesian tsunami of 2004. Tsunamis are cataclysmic natural forces, yet they are also part of life for island nations. Nowadays the human politics around disaster aid to economically derived regions, and tragedies such as the nuclear meltdown in the Fukushima Daiichi reactor, compound their impact. Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami features in this exhibition in Kentaro Yamada’s delicate dyeline prints of a bird’s-eye view of the waves before landfall. A series of serene rolling waves run counter to the televised images of destruction that followed. Traces of the 2011 Christchurch earthquake are here too, in Melissa Macleod’s large sieves made from the roots of pine trees from the Avon Heathcote (Brighton) estuary damaged by salt water following the earthquake. The sea leaked into the land and the trees died slowly from salination. Macleod tenderly treats the roots with beeswax and turns them into quasi-functional objects. Just as Te Wheke’s tentacle was amputated by Kupe but the octopus lived on, Macleod’s title the slow amputation of her protective arm, registers the lesser-known environmental impact of sea-damage to tree roots, sculpturally transformed over time.

Deftly reassembling the kind of urban flotsam that might wash up on a beach, the ‘little stars’ of Ani O’Neill’s ’etu iti (2006) are crafted from kikau (coconut midrib), feathers, raffia, shells, beads, sequins, videotape, recycled plastic and nylon yarn. Encased in these star clusters are intensified stories that draw on the imperative for eco-social repair, and the joy that comes from collective acts of making. While O’Neill’s materials are light, Joe Sheehan’s beach-combing turned up a scrunched plastic milk bottle on Makara Beach in 2008; then he took this piece of refuse as the inspiration for a carved milk bottle of the same dimensions in greywacke stone, enigmatically named Mother. The Makara stones unquestionably belong on the beach of their name, yet plastic molecules are now also tiny constituent parts of the oceanic mother, found even in the remotest parts of Antarctic oceans. We ingest this plastic, and it has become our strange kin in a leakage between animate and inanimate.

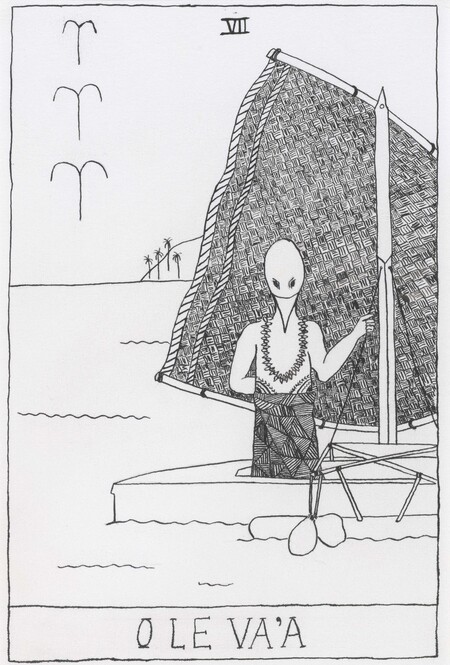

Lonnie Hutchinson Pigeon Tarot (detail) 2003. Ink on paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2004

In Moana cultures where mountains and seas are part of the cosmogeny, tagata or tangata (people) are often positioned as latecomers to the world of flux rather than a pre-eminent species. In a fusion of human and bird, the twenty-two fine ink drawings of Lonnie Hutchinson’s Pigeon Tarot series are encoded with imagery drawn from the tarot deck and from deep Samoan cosmology. As a sacred and spiritual symbol, the Samoan pigeon (Lupe) has a spiritual and autobiographical meaning for the artist and her journey across the waters of Aotearoa to the ancient Samoan star mound Tia Seu Lupe. Samoan star mounds are architectural stone platforms constructed for the pigeon-snaring sport of high chieftains, and woven into ritual ceremonies in the 1800s. Hutchinson’s long-standing interest in pre-Christian indigenous religion and knowledge emerges at an ecological moment when loss of habitat from deforestation is threatening birdlife.

While Hutchinson’s figures metamorphose into birds, Connie Samaras turns her video camera on an oxygenating Antarctic Weddell seal, appearing suddenly from an ice hole in the Ross Ice Shelf. The large close up of the animal’s face as she closes her eyes, breathes and then opens them again to look directly into the camera invites our empathy. The four minutes of repetitive breathing attunes us to our own patterns of breathing. Although we dwell in the same air and swim in the same ocean, wild beings like this seal make up less than four percent of all mammals on earth, the remainder made up of ‘us’ and the animals we farm for our food. Our unsustainable habits of consumption are brought home equally by Graham Bennett’s sculpted whale-meat tins.

How will Te Wheke, the octopus contend with a warming sea? When we hear about sea-level rise human losses of habitat are inevitably foregrounded, yet the effects on the ecosystems out of step with a warming ocean are already causing mass marine extinctions. In Angela Tiatia’s Lick (2015) four limbs hang, suspended and tentacle-like, in a liquid sea seen from an underwater lens. Small reef fish pool around the seaweed-slow movement of arms and legs as Tiatia floats gently with the lagoon’s swell. Her head and torso on the surface are dematerialised in the video currents, but eventually her whole body sinks and drifts backwards into the watery swell that pulls her out of the frame. The fish resume their business, unperturbed by the body carried away by the tide. In this lush lagoon world, beyond the hyper-sexualised, mainstream media treatment of the female body, Tiatia becomes more fish-like than gendered.

As coastal dwellers, the artists in Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania remind us that our fate is as intimately entwined with the ocean as the sea creatures of the deep. The long tentacles of Te Wheke reach out to us through these artworks to offer inter-species connection. The “tentacular thinking” proposed by philosopher-feminist Donna Haraway might be just what is needed to collectively make kin with the Ahuman worlds.5 Amongst human cultures too we are called to Lana Lopesi’s pan-island provocation, “how do we get to know each other again?” Art offers oceanic flows to unsettle the subjective binaries between the them and us of nation states, to suggest instead a collective response to the wero (challenge) of the conditions of the Anthropocene.

Acknowledgements

Fa’fetai lava, I am grateful to associate professor Albert Refiti and Lonnie Hutchinson for their advice on this essay.