B.

Peter Vangioni looks at John Gibb From The Foot Of The Hills 1886. Oil on canvas. Christchurch Art Gallery Trust Collection

‘Where the picture stops and the world begins’

Behind the scenes

The way a work of art is framed affects our perception of the piece. A bad frame can detract and distract, a good frame enhances and even extends a work. While the Gallery has been closed we have updated frames for a number of works in the collection.

Curator Peter Vangioni talks about a recent frame discovery. ‘The Gallery has a frame store and there are a lot of old frames in there. While we’ve been closed I’ve taken the opportunity to go through these. One day I uncovered the original frame for a John Gibb painting, From the Foot of the Hills 1886. The work is currently framed in an ornate gilt Victorian style reproduction, with mouldings copied from an original Victorian frame. This frame replaced a 1960s style frame completely out of keeping with the era of the painting, and while the reproduction is suitable, I think the painting needs to be reunited with its original frame. Frame conservator Lin Klenner is working on the original frame, and when it is repaired we will restore it to its painting, and the reproduction frame will be reused for another work.

‘We try to look back at the style of frames artists used for their own works, even to the point of contacting colleagues to ask what style of frame artists favoured. When Te Papa organised the Rita Angus show William McAloon and I talked a lot about the frames on the Anguses in our collection. Cass was in a fifties era frame, but in the 1980s it had been refinished in a mottled blue, and we bought that back to a creamy gesso more appropriate for the work.

‘There have been other works that have been reframed while we have been closed. I think for me the most amazing transformation was Ivy Fife’s Railway Crossing, which is an oil painting circa 1945, canvas on board. But it had been framed as a work on paper with a big matt around it. So we took it out of that and put it in a 1940s era frame, and that just looks amazing. One great thing about re-opening with a collection based show and curating from the collection is that it does provide an opportunity to give a lot of works the attention they need.’

Exhibition technician Scott Jackson takes a special interest in framing, and has matted and re-framed a number of works for the re-opening exhibition. I asked Scott to tell us more about the reframing project. He talked about reviewing the works in the collection to determine the works that could benefit from being reframed.

‘We looked at the condition of the frame, whether its style, size and materials complemented the work of art and whether the era of the frame was appropriate for the work. Philosophies on framing change, and I’ve seen different opinions in my time at the Gallery. Some frames are made by the artists themselves, and there is a school of thought that strongly believes that a work of art should remain in the frame made or chosen by the artist. Others would say, how are we to know that the frame chosen by the artist was not a choice driven by expediency rather than aesthetic values? Sometimes the frame made by the artist isn’t well made, so there are practical considerations from a preservation point of view. Some might even question whether the artist is the best person to choose the frame for their work.

‘Sometimes when we acquire works the frames are poor quality. Sadly you do get real estate style trickery where a work will be reframed in a good looking, but shoddy frame for resale. Recently we bought a work which had just been reframed, and the frame looked good at first glance, but when you looked closer you could see that the maker had cut corners. It was a really cheap pine frame and the painting’s stretcher had been screwed directly onto a raw MDF board. It’s always a bit disappointing when you see work like that.

‘So once you determine that a work needs to be reframed it’s a case of ordering the appropriate frame to be made and then taking the work out of its old frame to be reframed. This can be tricky and fascinating in equal measure, especially if you are dealing with a work that hasn’t been reframed for hundreds of years. You never know what you’ll find when you open up an old painting, I’ve found chicken feathers from the 1700s.

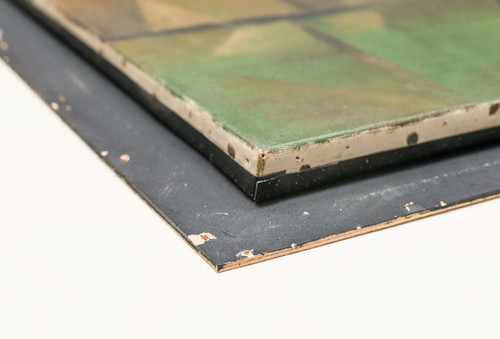

A frame removed from a work

Detail of a work being reframed

‘I reframed The Physician by Gerrit Dou a few years ago. The Gallery had the work down as an oil on canvas, but when I got it out of its frame it became clear that it was actually painted on a thick sheet of copper. There is added pressure when you’re reframing an old work. I remember not long after I started at the Gallery de-framing Panier de Raisins by Henri Fantin-Latour, which is a significant work. I was in the workshop pulling out the old nails; I looked behind me and there was the Gallery management team nervously watching in the doorway.

City Art make most of our frames. Most of the time we do the actual matting and reframing of the works ourselves, but sometimes we outsource this, for example recently we asked City Art to float mount a number of large Max Gimblett works. When it comes to matting the works, we use two colours, a soft white and an antique white. We used to use more coloured mounts, but they’re rather out of vogue now. If you look at the Margaret Stoddart exhibition that is part of the re-opening show you’ll see lots of different styles of frames and mats packed in together.

‘When cutting the mat board you work out how much of the work you want visible. With a print you generally want to see the edge of the plate. It’s a bit trickier with photos and paintings, as the edge of the work can be ambiguous. The ideal mat measures the same top and sides, and is wider at the bottom. This is called weighting and it’s to do with the way the eye rests on the work. If you get the dimensions right it looks like the mat is the same width all the way round, but if it actually is the same width all the way round it looks unbalanced. Once the work is in a mat it is backed with museum quality archival board, placed in the frame and sealed up with tape. The work is then essentially in an archival capsule.’

Peter has another framing project planned. ‘One project I’d really like to do is go through all the old frames and match those original frames with their works. In the 1960s there was a massive programme to replace all the Victorian frames because they were all ratty and broken, but they reframed them in 1960s frames, so it has been an ongoing programme to rectify that. I can imagine that at that time they probably didn’t have the skills to repair the original frames. Also in the 1960s there was a reaction against the Victorian generation. Bill Sutton said something along the lines that half the paintings in the McDougall were only fit for a bonfire, he was referring to the Victorian paintings, but it’s interesting how that swings around again with another generation. I just hope that in sixty years people are not looking at the frames we’ve created and going: ‘Oh my God, what were they thinking! What have they put that Colin McCahon in?’

The title of this article is a quote from artist Howard Hodgkin who is known for integrating frames into his work, blurring the border between artwork and containment. Frame buffs might also enjoy this article in the Guardian on the importance of framing.