The pleasure of making: objects taking centre stage in the space of the art gallery

Judy Darragh Gold Box 1989. Wood and plastic painted gold. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1989. Reproduced with permission

Was it serendipity that the opening of Christchurch Art Gallery's Burster Flipper Wobbler Dripper Spinner Stacker Shaker Maker coincided with that of Slip Cast, a group exhibition at the Dowse Art Museum that also focused on the pleasure that artists take in manipulating materials in the process of making art?

Where Burster Flipper claimed that 'Artists from near and far test the limits of their materials', 1 Slip Cast announced that 'ceramics are back ... New generations of artists are using ceramics ... incorporating other materials ... heedless of the traditional art/craft divide.' 2

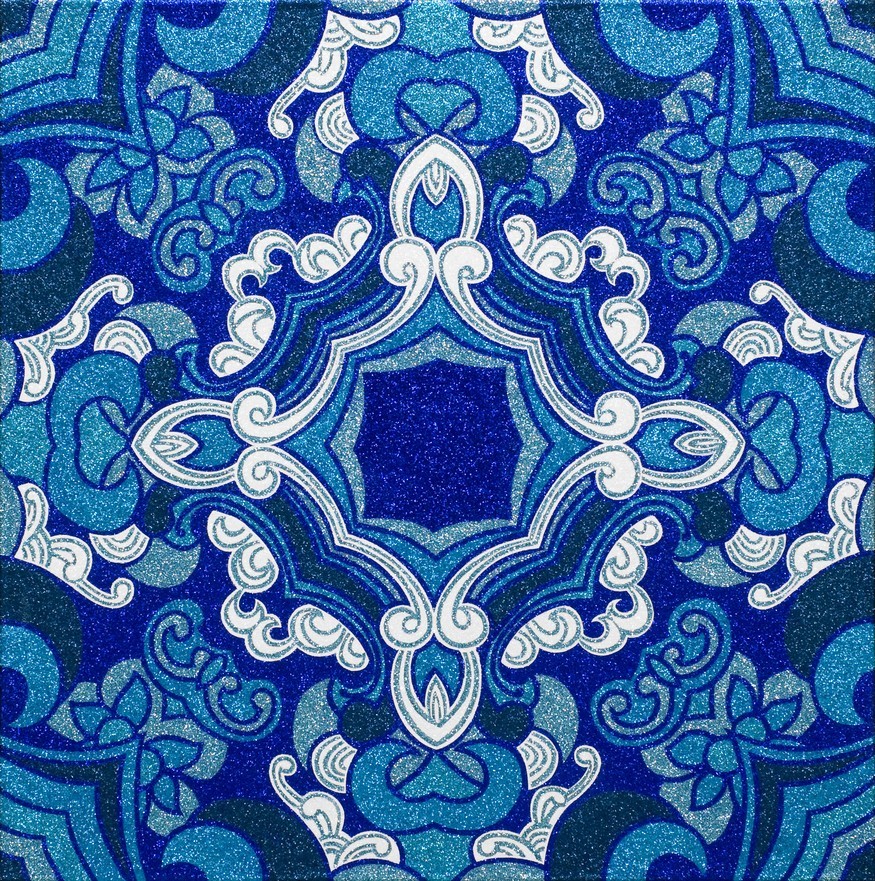

Moreover, a number of the artists included in Slip Cast also featured prominently in Freedom Farmers, Auckland Art Gallery's recent survey of contemporary New Zealand art – notably Tessa Laird's The Politics of Ecstasy (2013), an installation of colourful and curious ceramics, and Isobel Thom's equally arresting installation of teapots, jugs, rocket stoves and bowls. So, is this shared interest in objects (their crafting and materials) in recent exhibitions in three of the country's principal public galleries simply coincidence? There is ample evidence to suggest otherwise. Many of the artists in Burster Flipper specifically commented on the act of making and use of materials in interviews for the exhibition. John Hurrell singled out the artwork as 'object' for particular attention in his title – Things (A Baker's Dozen): Five whatsits, two thingummies, two doodahs and four thingies (2013) – and also observed a shift in his thinking about making art: 'As I get older I'm enjoying colour and texture more and more.'3 Likewise, in discussing Spinner (2011), Miranda Parkes commented that she loved 'the physicality of painting. ... I think there are valuable limitations and therefore possibilities that come through when ideas are tied to, and mediated through, a physical medium like paint.'4

Tessa Laird The Politics of Ecstasy (installation detail) 2013. Hand-built ceramics, earthenware with ceramic paint, painted second-hand wooden furniture, custom-built shelves. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

So where has this seemingly unanticipated preoccupation with highlighting materials and process come from? There are claims – not without an element of truth – that it represents a reaction against the predominance of an intrusive digital/virtual world through a newfound desire for authentic, handmade objects. Richard Orjis, a participating artist in both Freedom Farmers and Slip Cast, commented that the attraction of clay resided in its materiality: 'It's a way to celebrate the ... joy of the handmade; it's a reaction to or critique of the fast-paced streamlined art world.' 5

However, possibly of more import are changing perceptions about potential conflicts of interest between the crafting of the art object and its conceptual framework. Commenting on Erica van Zon's recent exhibition at City Gallery Wellington, The Light on the Dock, curator Lily Hacking observed that our understanding of van Zon's ceramics is 'transmutable, shifting, the objects [are] often overtly resistant to traditional systems of categorisation and display.' 6 Damian Skinner, curator of applied art at the Auckland Museum, has also recently noted that in contemporary craft, 'materials and skills are placed in the service of ideas, rather than being celebrated ends in themselves.' 7 This is a view also sanctioned by craft theorist Glenn Adamson, who maintains that 'skill as a management of risk [in making art] is not just a technical matter. It is fixed firmly within the decision-making process'. 8

For an artist like Judy Darragh (also participating in Burster Flipper) the attention that Adamson and Skinner give to the object as the outcome of an intimate relationship between making and ideas is hardly news. In 2004 she observed:

Objects aren't just that; crafted, fabricated or found objects. The object is the focus of the idea. The work becomes something that stands for the process of making, and the collective observation and consideration of making. ... Heart and hand. 9

Isobel Thom Untitled (installation detail) 2013. Ceramic prototypes: teapots, cups, jugs, planters, rocket stoves, bowls and flat plates. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

A new generation of artists/jewellers/designers certainly agree with Darragh, with the former life of a found object and the historical narratives that its materials bring to an artwork now accorded a greater degree of respect in contemporary practice. Darragh further observed:

I've had a longstanding love affair with the found object. These objects have had another life, and there can be a continuation when they are drawn into work .... it's like the object already has a personality. This challenges the mystique of the original art object. And modern consumerism. 10

Darragh frequently discusses her work in terms of its 'other lives.' Her installation of painted corks in Swarm II (2014) has its origins in earlier works and her ongoing collection of corks from wine bottles; Darragh acknowledges that the additional 300 required to fill the space in Burster Flipper served as a reminder of the social occasions where her source material had come from – 'everywhere and everyone'. 11

As a new generation of artists respond to a desire for a more direct engagement with the handmade, the priority that Darragh has accorded to materials and process for more than twenty-five years is reflected in the work of many emerging and mid-career artists in New Zealand, including Steve Carr, Eve Armstrong and contemporary jewellers like Renee Bevan and Ross Malcolm.

Taking their lead from Darragh, artists such as Malcolm and Bevan also challenge traditional beliefs about what makes an object precious. How can jewellery be 'precious' when it is made of discarded items or found objects? Recently participating in Handshake (a mentoring project for arts graduates set up by teacher and jeweller Peter Deckers), 12 Darragh mentored Kristin D'Agostino, who made rings and brooches from fishing line and plastic takeaway containers – where else could the value of such work reside but in its idea and making? (Possibly with some degree of contrariness, Hurrell's and John Nicholson's contributions to Burster Flipper also makes use of plastic – that most humble of industrial materials.)

Renee Bevan Bubblegum brooch 2013. Bubblegum, pin, paper. Collection of the artist. Courtesy of the artist and The National

Discussing the qualities and characteristics of contemporary jewellery, Damian Skinner observes:

At its most productive, the critique of preciousness encourages contemporary jewelers to continually question the field itself, to renew the arguments about value that sit close to the heart of jewelry's legacy, and to draw on the techniques of art and craft to explore how the jewelry object can propose new conclusions about the body and society. 13

Skinner and Adamson have both considered the conception and making of objects outside familiar definitions of art and craft that have been predominant for the past thirty years, and in doing so they draw attention to the long-serving and questionable nature of such distinctions. Published in 2010, British ceramic artist Edmund de Waal's The Hare with the Amber Eyes also addressed these concerns, highlighting the way in which objects in wider social spheres represent other values and perceptions of preciousness. 14 De Waal traced the history of his family's collection of seventeenth-century Japanese ceramics from the 1870s to the present day, documenting changes in ownership and the location of the works, giving prominence to their history as central to their substance and worth.

De Waal has also raised questions about prevailing distinctions between craft and art by focusing on the intimate and longstanding relationship between craft and the avant-garde throughout the twentieth century. He maintains that 'it is precisely because clay can be seen as practically worthless that so many artists have been able to use it as a material in exploratory and digressive ways'. 15 This has encompassed Picasso's ceramics and Jeff Koons's love of porcelain. He observes that Koons shamelessly admits it: 'Everyone grew up surrounded by this material. I use it to penetrate mass consciousness – to communicate to the people.' 16

Judy Darragh Swarm II (detail) 2014. Corks, paint, wire. Courtesy of the artist and Two Rooms Gallery

Similarly, Adamson observes the vital role that craft, and its emphasis upon the qualities of materials, occupied in the development of Process Art in the United States in the 1960s. Rejecting the notion that works of art encompassed an experience of spiritual or emotional values, Process Art sought to reveal only materials and methods:

[There] was never a time at which craft was fully sidelined from the discourse of modern sculpture. In 1962 ... Robert Morris was already beginning to work with plywood. His recollections about this moment make it clear that ... craft had a profoundly liberating quality. 'At thirty I had my alienation, my Skilsaw, and my plywood ... When I sliced into the plywood with my Skilsaw, I could hear, beneath the ear-damaging whine, a stark and refreshing "no" reverberate off the four walls: no to transcendence and spiritual values, heroic scale, anguished decisions, historicizing narrative, valuable artefact, intelligent structure, interesting visual experience.' It was from this attitude that Process Art, the most craft-like of the twentieth-century avant-gardes was born. 17

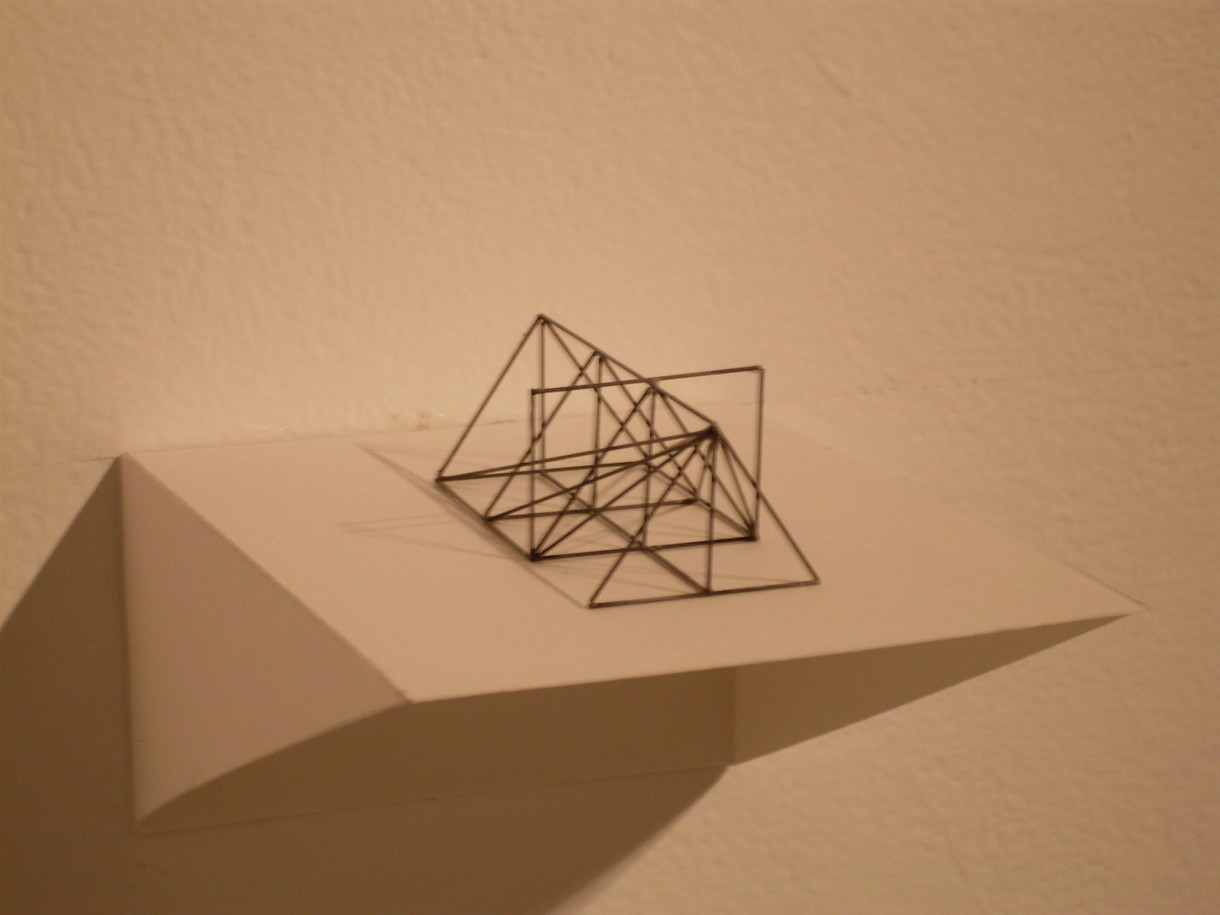

Discussing Swoop (2013) – his installation of ceramic objects and wooden shelves (fixed deceptively loosely to the gallery walls in Burster Flipper) – Tony Bond talks specifically about the importance of making to realise the idea. He notes:

[With] these ceramic works the intimate involvement with the media and the initial open approach means judgement calls are continually being made throughout the making processes. ... The work builds on an idea, the outcome isn't predetermined. 18

Like the majority of participating artists in Burster Flipper, or Slip Cast and Freedom Farmers, Bond recognises the constraints of working with particular materials. He articulates an attitude that encapsulates fundamental challenges for any artist, recognising that some measure of solution to questions about the success or otherwise of a work is found in the process of making – a proposition possibly best summarised by Isobel Thom, who comments on her recent engagement with clay as part of her practice: 'limitations are your best friend.' 19

Warren Feeney

Warren Feeney curated and managed Kete 2014, a contemporary craft symposium and art fair for the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts and International Festival of the Arts in Wellington (27 February – 2 March 2014).

John Hurrell Things (a Baker's Dozen): Five whatsits, two thingummies, two doodahs and four thingies (detail) 2013. Plastic peg baskets, nylon cable ties, label ties, plant ties, washers, rawl plugs, shower curtain rings. Courtesy of the artist