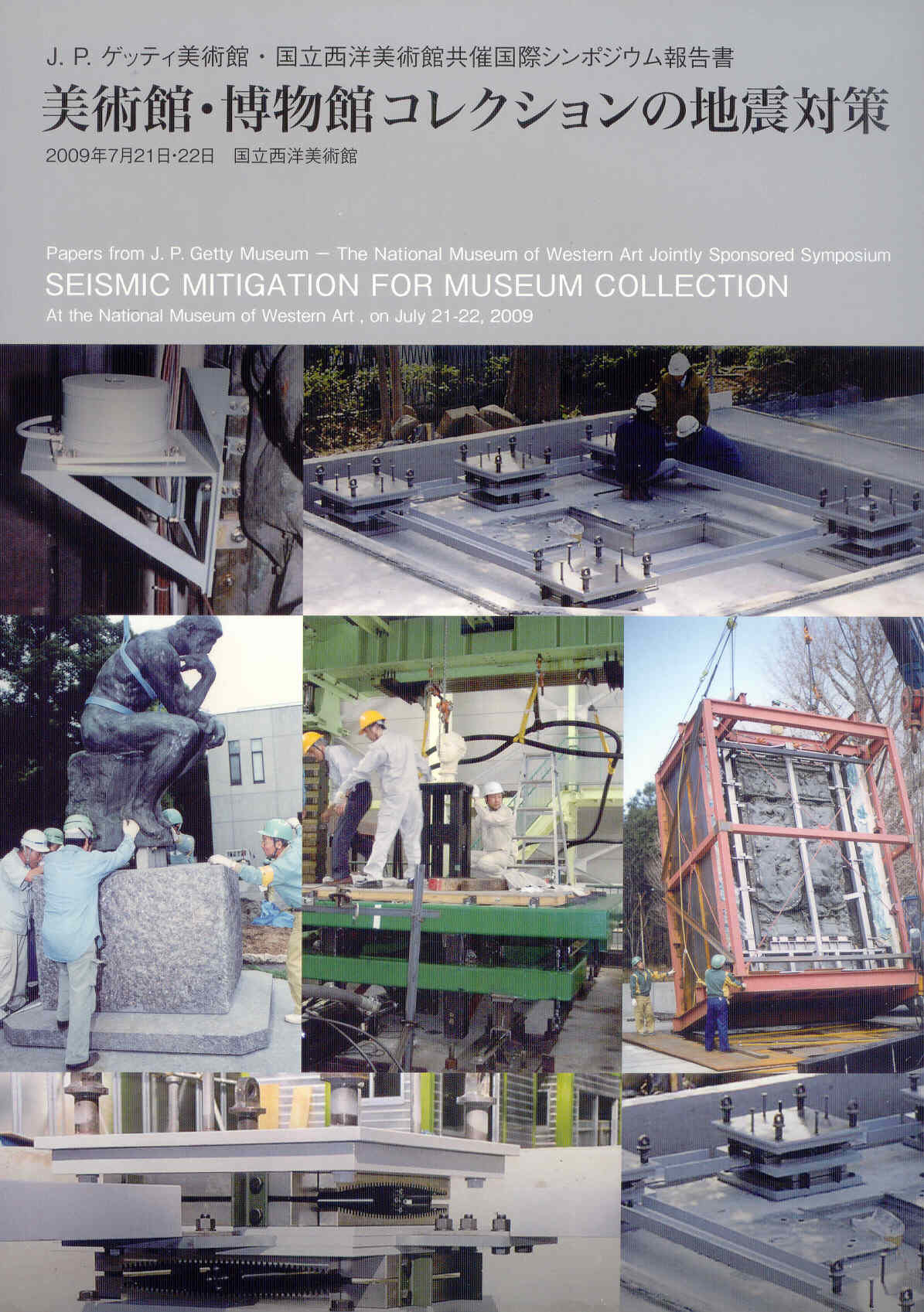

Cities of Remembrance

Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre Fisher Body 21 Plant, Detroit. Photograph. Reproduced with permission

Nothing was more fascinating than ruins to me when I was growing up in one of the newest parts of the New World—new, anyway, to extensive buildings and their various forms of lingering collapse and remnant. The native people of California had mostly built ephemeral structures that were readily and regularly replaced and left few traces. Anything old, anything that promised to reach into the past, was magical for me; ruins doubly so for the usual aura of romance and loss that, like death, is most alluring to the young who have not seen much of it yet.

We tear down and replace ruins in thriving cities, because we want those spaces to be useful, inhabitable, productive again. The ruins in other cities – Antigua, Guatemala, Detroit, Cambodia – are there because nothing has replaced them, because the city is in decline or even dead. And yet to thrive, cities need to be of the past as well as the future. Amnesia is one of the curses of prosperity, which will ruin continuity, tradition, local and fragile parts of the community while keeping the buildings standing, or replacing the old with the new. Too much can be swept away in the name of progress and profit. Although Manhattan’s cast iron district mutated into SoHo and its once-ruinous, renegade-inhabited Chelsea Piers are now bland-faced sports arenas, too much has been erased from too much of that city; like San Diego’s downtown it is like a theme park of itself.

Maybe there’s an inside-out kind of ruin that is the ruin of memory: that’s what a city of fully profitable, fully exploited, shiny new spaces can be. It has everything for the wallet and nothing for the imagination, which needs to stretch backward to be able also to stretch forward. It is a city in which the past has been ruined, as both actual place and as space for memory. For ruin also means to spoil something, and in this sense the pumped-up polished cities of maximum commercial potential are deeply ruined, not least because they are so lacking in actual ruin.

The past exists in a city as memorials, monuments and inscriptions, but also as old buildings, as institutions and sites of continuity – a stable, a church continuously hosting mass for one century or for several, a parade threaded down the same boulevard on the same festival day. And as ruins. Ruins remind us that all this is only provisional, that nothing lasts forever, that another day will come and with it another order, or another disaster. Ruins are parts of the city not forced to be productive in the present. They are spaces and structures that, although they have in a sense retired from work (or at least from ordinary productivity), produce the extraordinary and the unquantifiable out of which every great city must be made. The cities that are too ruined are tragic. But the cities without any ruins at all are shallow. How to have a thriving city that is not amnesiac, not all about profit and nothing more, might be about finding the balance between erasing and preserving ruin. Although of course how to have a thriving city is the great problem for the rust-belt cities like Detroit and Toledo and Cleveland.

At the site of a ruin, you pause, you contemplate. Time and space open up a little. You might remember the specifics of why this ruin is there or the sweetness and sadness of all transience. Every ruin is a window into the past, whether the long past of entropic processes or the sudden past of a revolution that smashed up monasteries or bomb that took out neighbourhoods. If a ruin is a place that is not doing the ordinary work of cities, it is because it is doing the extraordinary work, the deep work that matters most, the work of remembering, connecting, caring, and belonging.

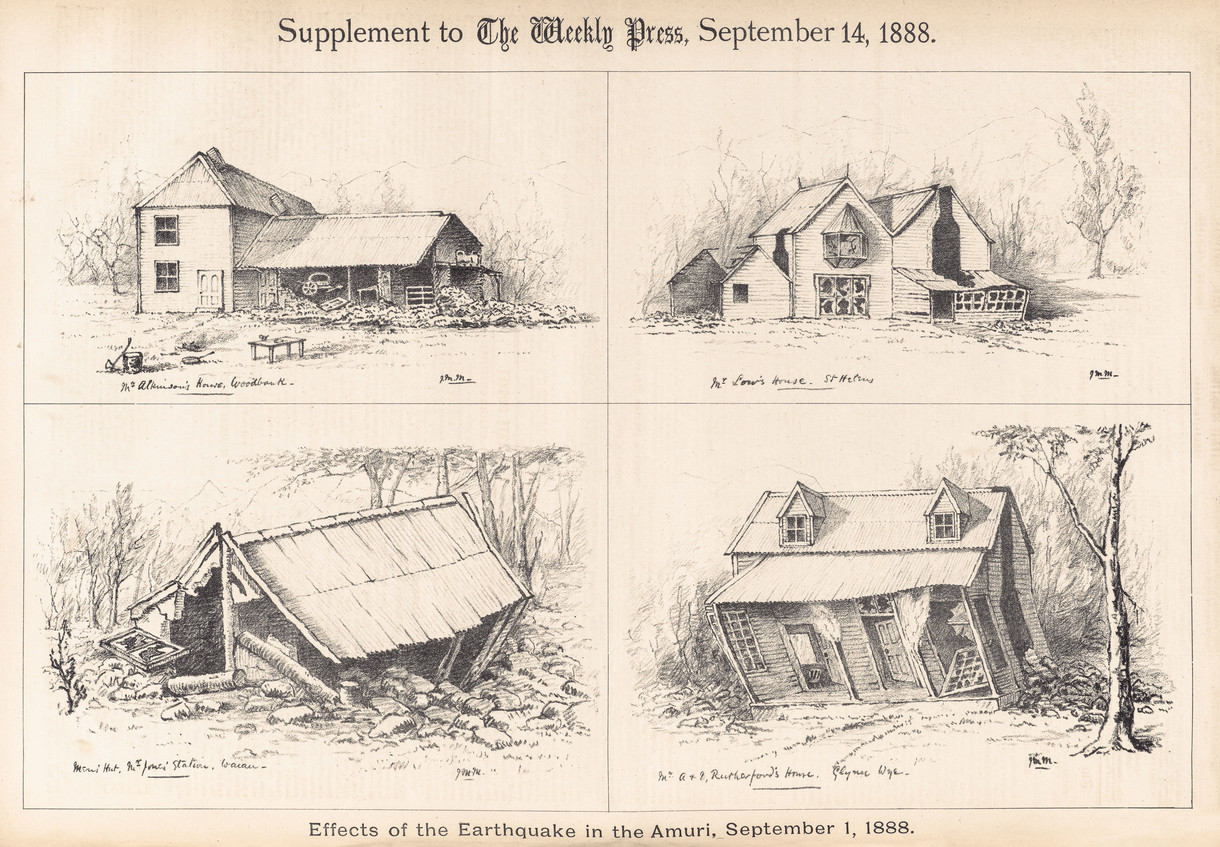

Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre The Palmyra

Apartments, Detroit. Photograph. Reproduced with permission

Not much is more difficult for me to look at than ruins now that I have travelled extensively in the wreckage of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, the Tohoku region of Japan since the tsunami and in Detroit since the economic earthquakes left it with half its population vanished, the rest impoverished; trees of heaven taking root on the un-cleaned crevices of high-rise buildings and whole neighbourhoods turning back into meadows and forests. I have seen what pain can be associated with ruin.

I don’t want cities that are nothing but pain. But I don’t want anaesthetised, amnesiac cities either. Surely there is a middle ground. Certainly there is a difference between new and old ruins as colossal as that between Port-au-Prince and Pompeii. And a difference between ruined cities and thriving cities that retain some ruin as a site of reflection and respect for those who suffered and died. And even with more recent ruins there are differences that matter. There are structures that fall into decay because of abandonment: roofs fall in, mortar corrodes, animals take over and plants begin to thrive. These are gentle ruins in which natural processes overtake the built environment, so that what is the decay of the constructed is the triumph of the wild.

But this variety of ruin often nowadays arises from the ungentle rearrangements of economies, perhaps most extensively in the abandoned industrial buildings and cities of the global north. These are the ruins of globalisation, in which cars and washing machines and clothes are made in the sweatshops of the south, creating another kind of ruin – abandoned villages, abandoned agrarian societies, abandoned food security and independence from the vagaries of the market. In many cities such as my own, San Francisco, and New York, this industrial abandonment was overtaken by new uses for the buildings – witness the lofts of SoHo, formerly a manufacturing district in lower Manhattan – so that little remains to remind anyone that the economy and employment were once very different.

‘The built environment is only the placeholder, not quite the place that is a city, just as the brain is not the mind.’

And then there are the ungentle ruins, the buildings that collapsed in a day in Baghdad or Kosovo or Kobe or Christchurch. Even in the sudden collapse of a building, a neighbourhood, a city, the distinction between war and nature matters. There is less malice in the latter, and fewer politics. It is also important, however, to recollect that disaster sociologists like to say that there’s no such thing as a natural disaster. When I went to the earthquake-shattered city of L’Aquila in central Italy a few months after the earthquake there, I was told, ‘ In California no one would have died.’

It’s not generally earthquakes that kill; it’s the collapse of the built environment that a quake causes. How hard it falls depends on whether you have the unregulated jumble of a poor place like Haiti or the high standards of Japan or California. And in many places the poor live in the vulnerable areas, so mortality is another of the prices for being unable to pay (though one of the peculiarities of my home state is that there the rich choose to live on beaches, on landfill, crumbling cliffs and fire-prone ridges and canyons, where they receive unreasonable amounts of protection and recompense when the inevitable comes again).

Ruins are painful – and yet like bodies, cities have scars, and they are part of the history of the entity. Perhaps removal of all traces of trauma can be thought of as akin to plastic surgery or amnesia, erasing the past, erasing the true age and experience of a place. Which is not to justify or celebrate cities in ruins, but to imagine that perhaps some ruins are worth keeping. When I first went to London in 1976, at age fifteen, there were still traces of the Blitz. In many ways that was London’s finest hour, and perhaps some trace of what a cratered, shattered city the cheerfully defiant Londoners lived in should have been kept alive. In Coven - try, the medieval cathedral half-destroyed by German aerial bombardment on 14 November 1940 was left as ruin – as a site of memory. To rebuild it would have been to turn a medieval into a modern structure or a facsimile of itself and perhaps to erase the ordeal. Leaving it and building a new cathedral for worship means that memory remains alive – memory of death and loss – and life goes on.

My city has only one real monument to the 1906 earthquake that, thanks to the terrible response of the authorities, resulted in fires that burned down half the city. It’s the fire hydrant that, when all the rest were dry, miraculously had water: ‘the hydrant that saved the Mission district’. We – locals, city officials, firefighters, the Red Cross – celebrate the earthquake anniversary at 5:06am every year at Lotta’s Fountain downtown, and then at dawn some of the celebrants zip across town to spray-paint the hydrant gold all over again. It’s not much. Those of us who are deeply rooted in the place might remember what happened in 1906 and have lived through what happened in 1989, but a lot of people are young, transient, recently arrived, and nothing tells them that all this is temporary, contingent, just pretending to be stable and secure until ‘the big one’ comes.

The built environment is only the placeholder, not quite the place that is a city, just as the brain is not the mind. After the 1906 earthquake the writer Mary Austin remarked that ‘ It comes to this with the bulk of San Franciscans, that they discovered the place and the spirit to be home rather than the walls and the furnishings.’ Her city didn’t burn down so much as it rose up; it was a city of people, not of buildings. Ruins commemorate what became of the structures but something more might be needed to recall the ordinary heroism of people in disaster. We have too many monuments to faraway wars of dubious merit and not nearly enough to the civilians who risk their lives at home. And maybe not enough ruins.

The illustrations in this article are taken from Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre’s The Ruins of Detriot (Steidl, Germany, 2010)