Otira: it's a state of mind

A short road trip to the Otira Gorge was the scene for a conversation between Gallery curator Peter Vangioni and two of the artists included in Van der Velden: Otira, Jason Greig and the Torlesse Supergroup's Roy Montgomery.

On 19 January 1891 Petrus van der Velden set off from Christchurch for the Otira Gorge. The journey through the gorge had already earned a reputation as one of the world's most spectacular coach trips, and was popular with artists of the time. The Otira was to become almost an obsession for van der Velden, and in it he found the motifs for which he is now best known. Retracing the artist's journey today are curator Peter Vangioni and artists Jason Greig and Roy Montgomery. Along for the ride are Bulletin editor Davey Simpson and the Gallery's photographer John Collie. The journey that van der Velden made could take three days in a canvas-covered wagon—our wagon is a Toyota Camry, and our time considerably shorter. We're aiming to be back at the Gallery by four.

However, it's still a long drive, so we make a few stops along the way. The first is at what would have been van der Velden's first night's rest—Porters Pass and Lake Lyndon. The hotel that he stayed in is now long gone. Here Montgomery, who lectures in environmental management at Lincoln University, points out the wilding pines that are spreading out across the landscape. Now classified as weeds, they were originally part of erosion control projects run in the Cragieburn Range; interestingly, they can be seen in Rita Angus's Cass. According to Montgomery, during the 1930s and 1940s the eroded slopes of the region were portrayed by some scientists and conservationists as directly analogous to the Dust Bowl in the US, with overgrazing the major problem. Later research demonstrated that the erosion had more to do with rainfall and natural factors than grazing, turning on its head much of the rhetoric of soil conservation in New Zealand, but by this time the tree planting had taken root, altering the landscape from that which van der Velden would have seen.

We pass through Castle Hill Village, close to the site of the Southern Oscillation—a 2005 sound performance event at which the Torlesse Supergroup's Transect, from their forthcoming album, was performed. Once envisaged as becoming the 'Aspen of the South Island', it now appears frozen in time. Our next stop is Bealey, a cluster of houses, baches and a hotel, and van der Velden's second night's resting place. Just outside of Bealey we pass a line of pylons, stretching out across the braided expanse of the Waimakariri and down the Bealey river. These Greig points out as the fruits of his father's work as a surveyor and the reason for his childhood visits to the region.

Through Arthurs Pass we finally reach Death's Corner, and the viewpoint at the top of the Otira Gorge. With one notable exception the view is still pretty much as illustrated in Charles Beken's 1910 photograph. That exception of course is the viaduct that now snakes its way through the steepest section of the gorge—which Greig compares to a 'self-medicating wound'. From here we can still walk a section of the old road, which appears to have been swept away by one of many landslides just a little further on. Greig collects a couple of small rocks, which he later explains will be used as source material for the piece he plans to exhibit.

At the bottom of the gorge we stop to look at Mount Rolleston and search for the plaque that marks the site of the old Cobb and Co. coach stop, the George Dyer Hotel, where van der Velden spent six weeks in 1891. We can't find it, but the view is familiar as the Gallery's Mount Rolleston and the Otira River, although it looks as though van der Velden chose to open his view out for dramatic effect. Just down river a crane is using a piledriver to work on the bridge, and the noise echoes around the entire valley in a way that appears totally disproportionate to the force it delivers. It adds to the faint air of claustrophobia that we have been feeling since entering the gorge.

From there we drive on to the Otira township. Vangioni explains that by the 1930s it had become a bustling railway town. Now, however, it has a sleepy, run-down air about it. The station lies at the centre of the town, but with only the occasional coal train and the daily TranzAlpine running through it the underpass feels a little unnecessary. We look up the hillsides and it's clear that soon they will be scarlet with rata.

'Otira: it's a state of mind' is the slogan on the t-shirt for sale inside the Otira Hotel. What state isn't made clear. Owners Bill and Christine Hennah talk ruefully of the old photographs of the region that they lost when they last leased out the business. When we show them the exhibition catalogue Christine lights upon Derek Henderson's 2004 photograph of children sitting on a rusty Datsun outside one of the properties. 'I remember them,' she says, 'We've painted that place since then, but it'll need a bit of work before it's ready to be lived in again. Not if we don't want people to fall through the porch anyway.' They tell us that there are now perhaps forty-three people living in the township, and maybe ten or so houses occupied.

Vangioni buys a t-shirt, and we sit down for a cheeseburger and chips. The door to the bar creaks ominously—it's a noise that Greig seems quite taken with:

Jason Greig: That's a good creak.

Roy Montgomery: The other thing this place does is that when the trains are hooking up it vibrates really nicely with their movements.

Peter Vangioni: The whole valley shakes?

RM: No, I think it's just this hotel.

PV: I first came to this hotel in 1989 after moving down to Christchurch from Palmerston North. That first drive through the Otira Gorge had a profound effect on me, and I've returned regularly ever since. It's such a dramatic landscape, and the way that it envelops the traveller—there's nothing quite like it in the North Island. When were you last here Jason?

JG: I must have been a very small child, so that's probably forty or so years ago.

PV: And what are your impressions now—does it live up to any expectations you might have had before the journey?

JG: To be honest, I suppose as a kid the scale of things was more overwhelming. It was only when we got to the viaduct that the scale began to match up with my memories. I suppose I had this romantic ideal of the place, but it's hard now to make the connection with what it would have been like without roads, and without the infrastructure that's there now. How that challenge would have coloured the images and how they would have been seen by people.

PV: Is the Otira township gothic? Would you recommend it for a weekend retreat?

JG: Well, I would!

RM: I don't know about gothic but I do regard it as genuinely West Coast, insofar as it only exists because of earlier government policies of frontier development. Its edge is that it once tried to be a real town in a trying location. Arthurs Pass is nice enough but it seems like the playful invention of relatively cultivated Cantabrians—I'd never visit Arthurs Pass without dropping in at Otira. I'd certainly recommend it as a stopover for a day or two if not as a retreat spot. I think the town appeals for its deserted quality and tranquillity. I don't enjoy seeing bits of it gone between visits but nor would I like to see it too refurbished.

PV: It's got a real edge to it, everything is decaying, falling down, submitting to the onslaught of the very wet environment... does the town appeal for its decaying qualities?

JG: Always one of the themes with me is decay, and the inevitability of decay. You put up barriers but eventually they'll be knocked or worn down. Otira's a pretty perfect example of people trying to place themselves, and not only being knocked back by the inevitability of the climate but also by bureaucracy and social pressures. I was quite surprised by meeting the owners. Maybe after fighting something for so long, it's just total acceptance and the relief that that brings, but Christine certainly didn't seem particularly down in the dumps.

RM: I asked them once what on earth made them buy a town. They said they just drove through and thought there was 'something special about this place' or words to that effect. It's a wee principality. When they bought it they thought it would be reasonably easy to subdivide, but that has proved far from true.

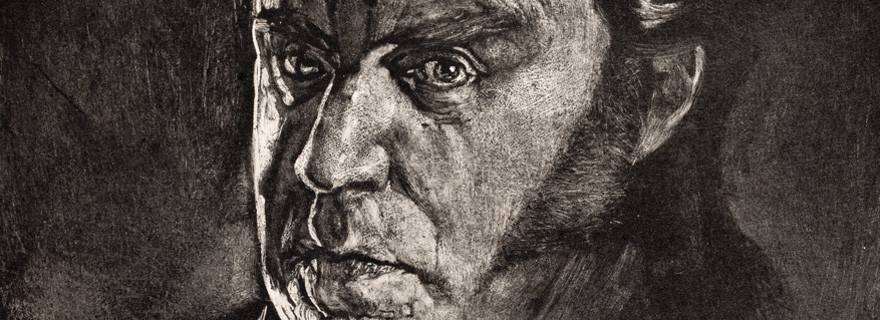

PV: One thing that is constantly reinforced to me as a curator at the Gallery is that van der Velden's paintings of the Otira are enormously highly regarded in Christchurch. He is one of the Gallery's most popular artists, with a wide fan base, young and old—the undisputed superstar of Canterbury colonial art if you like. Has he been influential on either of your work?

RM: I think like many people in Christchurch I was first made aware of van der Velden's work through a couple of pieces at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, both large and rather gloomy in their own way. But beyond that I haven't had much exposure so I wouldn't say he has been influential. I can see why he painted the Otira area repeatedly in that rather unsentimental fashion though.

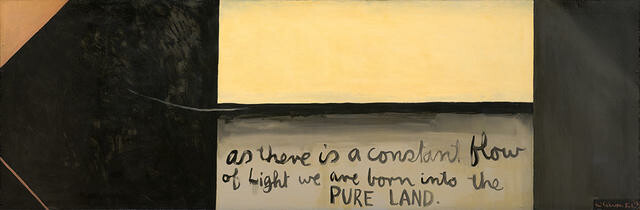

JG: And I see why you wanted me to make a work for the exhibition. There's a brooding romanticism, and I get that connection. Everybody goes on about this darkness, and I can understand that too. He's dealing with the gorge, and being in a new environment and the rawness and excitement of seeing something that hasn't been processed by humanity or tamed. I guess the analogy for me would be forces beyond his control, whereas my work is sort of about inner forces—my art is a way of getting that out. Purging it. There's a feeling of being overwhelmed by something and sort of making a stand. But I don't know whether we should be talking about darkness as much as light—light creeping in in spite of overwhelming odds, in spite of the overwhelming size of the landscape. That's what I notice about his works, the light is still there in his drawings—it creeps through.

PV: So Roy, your 1995 solo album Scenes from the South Island, was quite a departure from your previous work with bands such as the Pin Group, the Shallows and Dadamah. Many of the tracks

from Scenes from the South Island are, to me, very evocative of the drive up here to Otira from Christchurch. What made you record that album, and where did those tracks come from? It seemed to me that you stopped playing music in the rock tradition and began to make sounds that directly responded to the landscape—something you continue to do with your current outfit, Torlesse Supergroup.

RM: I think really the two things existed in parallel. I was doing the soundscape stuff and still doing song-based things at the same time. But I just kept them separate. I suppose the soundscape compositions suited albums more and the songs suited singles. I was trotting out singles roughly at the same time. It wasn't entirely a break from conventional song structure either—in a way it was a decision I made along the way of accumulating material. I thought these three-minute things belong on 45s and these are longer pieces or more connected in some way and they belong on an album. It wasn't really a big aesthetic leap or anything like that.

PV: And when you create a work, do you start with a specific idea that you want it to convey? I'm thinking here of tracks like the Torlesse Supergroup's Transect, which is included in the Otira exhibition, or your earlier Winding it out in the high country, which really does remind me of the sensation of driving fast through high-country roads.

RM: In my case, I think it's probably more about starting with something melodic. It might not be much more than a pattern, but once I start adding the layers to it, then it starts to evoke something visual or experiential. And then I start to add the top layers of the sound. So, like Nor-wester head-on, it might have been more pastoral to begin with, but it ends up being more like trying to stand up in a really strong wind. But I didn't know at the start when I laid down the first track that it was going to sound like that.

JG: So is it spontaneous?

RM: I don't know. I'm trying to do an interview at the moment where I get asked that question about improvisation and I don't quite know how to answer it. I rely upon a basic motif, which is not improvised. It's quite melodic, and it anchors the work, but then what I do over the top I could probably never repeat. It's a little like trying to be a band by yourself, where you say I need something to keep it going; that has to be reliable and quite premeditated.

JG: How are you doing that? Do you loop it or...

RM: No, I've never looped a thing. I struggle with all that newfangled technology. Even analogue loop stuff I've never really engaged with. I play the thing, ad infinitum if necessary, and then I start adding elements over the top and maybe the middle section might be alright, or the end.

JG: Have you got your own recording gear?

RM: Just a little cassette four track, which I've never progressed beyond. It's starting to show its age, so when that gives up I'm stuck.

JG: To me, this whole landscape has its own soundtrack. I mean, when we were down by that wee creek, it was bloody noisy—you don't realise until you step away from it. And here, the railway. It's the only reason the place exists, and it's getting rattled around by it.

PV: Jason, you and van der Velden both create incredibly moody landscape imagery through the use of dark tones. Do you draw the same parallels? You both seem to have a natural affinity with charcoal, which is a difficult medium—why were you drawn to it? Obviously you get similar dark tonal effects through your monoprints.

JG: Well now the monoprints have taken over, because they embody the same characteristics. But there's a visceral quality to the ink, which I seem to have an affinity with for some reason—it just seems I can manifest images even quicker with it. However, the charcoal definitely came first. And it was the blacks—I just really enjoyed the blacks, and then the greys that were close to the blacks tonally. Working in that chiaroscuro way, I just stumbled upon a way of drawing that intrigued me.

PV: How do you work with charcoal? Do you work towards darks, or do you carve the lights into the black?

JG: That's exactly what I started to do. The pieces of paper that I started working on, they weren't $10 sheets of Arches 88 or whatever, which I would have been freaked out about using. Initially, being on the dole when you come out of art school, you think about money, and you don't want to make expensive mistakes. So I got scrap bits of paper and just started experimenting. Working it and working it until you can't get whites because you've put so much charcoal on there—it's ingrained into the fibres of the paper. And you get this richness so that when something does come into focus an image just clicks. And then you realise that a piece of paper is actually wood and it's just as tough as old boots. So you start attacking it with sandpaper to open up the fibres so you can get the whites again. And then you start mucking around with sealing parts of the drawing halfway through to mummify them so that if you do smudge over areas you can easily remove that because there's a layer of lacquer. Then you realise that you can start really getting whites back by attacking drawings with razor blades. Subtly, and not so subtly at times. And you realise even more how tough the paper is. Not many people know that. You wind up with this catalogue of techniques that you can employ. It's the same with the monoprinting. There are endless possibilities for how to treat the ink, or the charcoal.

PV: This visit allowed you to view the landscape at first hand—will there remain any imaginative elements in your representation of the Otira landscape? And why did you collect those rocks at the Arthurs Pass summit, Goat Creek and the Otira township? What's the working method involved?

JG: Lately I was doing a wee maquette for my Jekyll and Hyde project and it just opened up some new possibilities. It seems like such a stupidly simple thing. But it's all about timing too I guess—when the time's right and the penny drops it might as well make a big clang. I just like the idea of making something in reality. So I'll use the rocks, build another wee maquette, light it up so I can get a physical idea of the landscape. But I kind of want it to be unreal. There's the thing—taking something that doesn't exist, and I suppose really couldn't exist, and making it tangible and as if it could really be real.