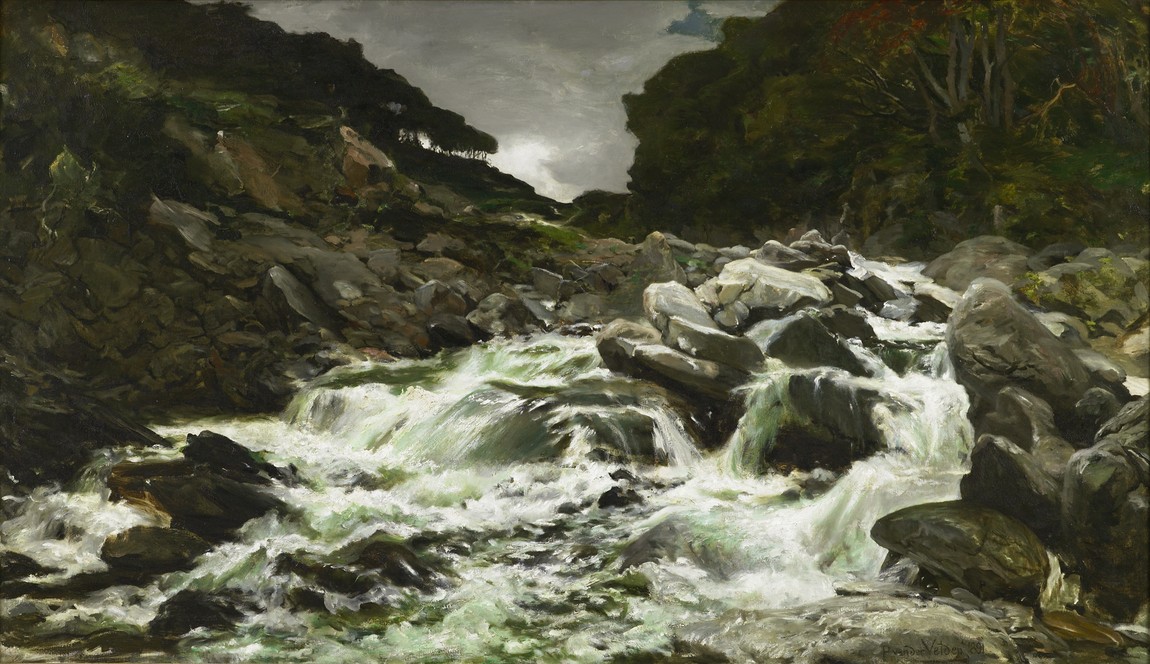

Van der Velden: Otira

Petrus van der Velden Mount Rolleston and the Otira River 1893. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1965

A first encounter with a painting by Petrus van der Velden more than twenty years ago was the start of many years of research for Gallery curator Peter Vangioni. Peter is the lead author of the Gallery's new book on van der Velden, and talks here of his fascination with the artist's Otira works.

Some time during the late 1980s a few mates and myself drove our rattly old Honda Civic hatchback into Arthur's Pass to climb Avalanche Peak via Crow Stream in the southern shadow of Mount Rolleston. The trip was a complete disaster due to a severe southerly storm that hit the area just as we began our tramp. The DOC ranger at Arthur's Pass recommended we cancel the climb, but at the invincible age of nineteen we naïvely thought we could easily manage the ascent, and pushed on. We were on the opposite side of Mount Rolleston to the Otira River, but the mountain dominated the entire trip, looming over us in the rain and snow and occasionally allowing us a glimpse of its peaks. We ended up trapped in the Crow hut for two nights before the storm cleared enough for us to make our escape back through the valley the way we had come. This included two seriously perilous crossings of the swollen Waimakariri river and to this day I still shudder at our foolishness (hearing the muffled sounds of rocks being carried down the river bed by the torrent, my legs feeling like they were about to give way to the force of the river's flow).

Later that year I went to the Robert McDougall Art Gallery for the first time, to see the Andy Warhol screenprint (I was the drummer in an obscure garage band heavily influenced by the Velvet Underground and Warhol's Factory). I found myself instead standing in front of Petrus van der Velden's Mount Rolleston and the Otira River, reliving my tramp up the creek bed beneath the mountain. I found I had a far stronger connection with this work than I did with the Warhol print, and even now I remain thankful every time I see van der Velden's painting, with its turbulent rushing waters over the broad rocky river bed while the darkest of storm clouds hang threateningly above the valley—very much the same weather we experienced at the junction of the Crow and Waimakariri rivers all those years ago.

The Otira Gorge and Arthur's Pass region is as spectacular today as it was when Petrus van der Velden first visited it in January 1891—a watershed moment, not only for the artist's career but also for the history of New Zealand art. Van der Velden's paintings of the Otira Gorge remain to this day some of the most powerful and emotive works to have been produced in New Zealand and have appealed to generations of art audiences since they were first painted 120 years ago.

In 1891 Otira was a must-see destination for any visitor to the country, a justifiable reputation that was enhanced by numerous accounts of the dramatic coach ride along the steep and narrow road. Awe-struck travellers related tales of the surrounding majestic mountains, the thunderous roar of falling water that reverberates throughout the Gorge, particularly when it rains, and the dense primeval bush that covers the mountain slopes. Many published descriptions from the late nineteenth century expounded the Victorian notion that to experience pure nature, untouched and unsullied by human hands, brought one into closer communication with God—a notion that appealed to van der Velden's thoughts on spirituality. His tempestuous visions of the Otira Gorge reveal his deeply personal ideas about God, nature and art:

Colour is light, light is love and love is God and therefore on Sundays instead of going to church I teach my children drawing after nature. I have come to the conclusion that painting and drawing after nature, instead of being a luxury is the most necessary for the education of man ... The aim is the most necessary for the education of man ... The aim of our existence is nothing else than to study nature and with so doing to understand more and more how grand and pure nature is.1

Petrus van der Velden A waterfall in the Otira Gorge 1891. Oil on canvas. Collection of Dunedin Public Art Gallery, purchased 1893

Van der Velden's first trip to Otira took place over January and February 1891, when he spent six weeks based at the George Dyer Hotel. His major Otira motif, that of a mountain stream, was developed out of his experiences on this visit, and his masterpiece A waterfall in the Otira Gorge was an undisputed success when shown at the annual exhibitions of the Canterbury, Auckland and Otago art societies in 1891 and 1892. The reviews he received suggest that van der Velden had made his mark on New Zealand's fledgling art scene. Comments such as 'The pride of the exhibition', 'the best picture of its kind [to have been] shown in Auckland' and 'the great feature of this year's exhibition' highlight the accolades he received at the time for this painting.2 Van der Velden had secured his position as one of the country's leading artists. Establishing his reputation even further was the £300 pounds paid for the above painting by the Otago Art Society, an unprecedented amount for a New Zealand painting at the time.

Van der Velden returned to Otira for a second visit in the winter of 1893. During this trip he developed his second Otira motif, that of Mount Rolleston, a view taken from in front of the George Dyer Hotel at the foot of the Gorge where the Otira and Rolleston rivers converge. As with his mountain stream series, van der Velden completed numerous versions of this motif, varying the atmospheric conditions from darkened stormy skies and flooded rivers to less turbulent scenes with the sun setting over the ranges to the west. With an almost obsessive zeal, he returned to them again and again throughout the early 1890s, exploring compositional and tonal variations.

In 1912, van der Velden returned to the Otira again, at least in his studio. He completed several studies of the mountain stream motif that ultimately led to his last major painting. Now in his twilight years, he had come to the realisation that the Otira series was one of his major achievements as an artist. This is clearly evident in Self-portrait with Otira background, completed just three weeks before he died, in which the artist pays modest homage to himself and his Otira works, proclaiming to the world the importance he places on his Otira paintings above all his other work from his long career.

Petrus van der Velden Self-portrait with Otira background 1913. Charcoal. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, bequeathed by Miss D.C. Bates, 1983

Van der Velden: Otira brings together for the first time a comprehensive collection of the Otira paintings and drawings, including the masterpiece A waterfall in the Otira Gorge, which will be shown alongside lesser known examples based on his mountain stream motif as well as examples from the Mount Rolleston series. Collectively these works highlight the artist's single-minded approach to painting the Otira, exploring the range of variations in his compositions. Alongside these will be exhibited a selection of van der Velden's sketchbooks, drawings and his last major work, Otira Gorge (1912).

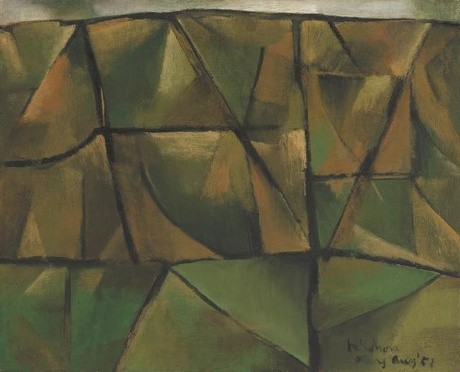

Artists who also worked at Otira, or have produced work influenced by van der Velden or his Otira motifs, will also be included. John Gibb, Charles Blomfield, Alfred Walsh, Margaret Stoddart as well as colonial photographers W.A. Taylor and the Burton Brothers will be shown alongside more contemporary artists such as Colin McCahon, Ann Shelton, Elliott Collins, Brenda Nightingale, Derek Henderson, Jason Greig, Rudolf Boelee, Andrew Drummond and the sound artists Torlesse Supergroup.

In 1997 I drove some friends from Chicago over the main divide via the Otira Gorge. Even from the comfort of our Nissan Sunny it was a revealing moment as we reached the top of gorge and began our descent into the ravine. The chatter fell to silence and there was a palpable sense of wonder at the dramatic landscape that was unfolding before us. I could also sense a little fear in our guests at the sheer drop over the side of the road. We stopped halfway down and were struck by the scale of the mountains that engulfed us—and not least the volume of the thunderous torrent crashing its way down the Gorge below us. This is a landscape that still inspires awe in much the same way as it did for van der Velden and his Victorian counterparts over 120 years ago.

Peter Vangioni

Curator

NOTES

-------

1. Quoted in T.L. Rodney Wilson, Petrus van der Velden (1837–1913): A Catalogue Raisonné, Sydney, 1979, pp.111–12.

2. In order: Lyttelton Times, 6 November 1891, p.5; 'Brother brush', The Observer, 19 March 1892, p.4; and The Otago Witness, 17 November 1892, p.15.

![Burial in the Winter on the Island of Marken [The Dutch Funeral]](/media/cache/81/09/810948cfa92f756f6d5ceb4f03044ac5.jpg)