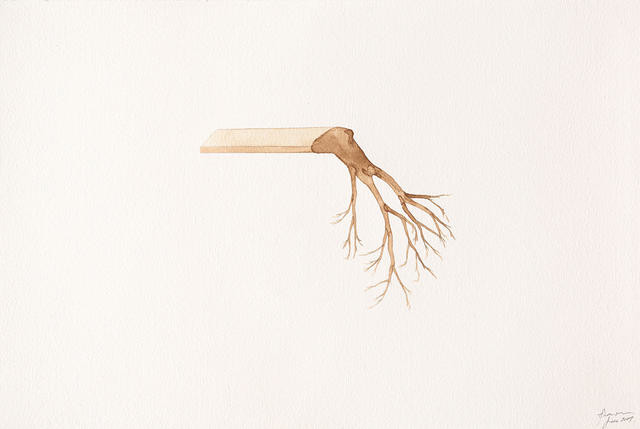

Zina Swanson’s precise, yet poetic painted drawings call attention to the delicacy and vulnerability of nature. Plant matter, insects and other tiny objects she collected over several years take fresh life in brushstrokes that range from feathery to forensically precise. Zina’s interest in her personal – and our human – relationship with the natural world led her to imagine a strange form of cross-species rehabilitation, where wilting forms are supported, a cutting grows the feet of a bird and processed timber receives new prosthetic roots. Her latest painting recounts an early foray into collecting, when she salvaged a discarded stick so large it had to be cut into three and reassembled in her studio. In an associated poem, she wrote:

Making them part of my life, by making them part of my paintings

Making a special shelf for them in my studio

The collection keeps growing.

(Perilous: Unheard Stories from the Collection, 6 August 2022- )