Rita Angus

Aotearoa New Zealand, b.1908, d.1970

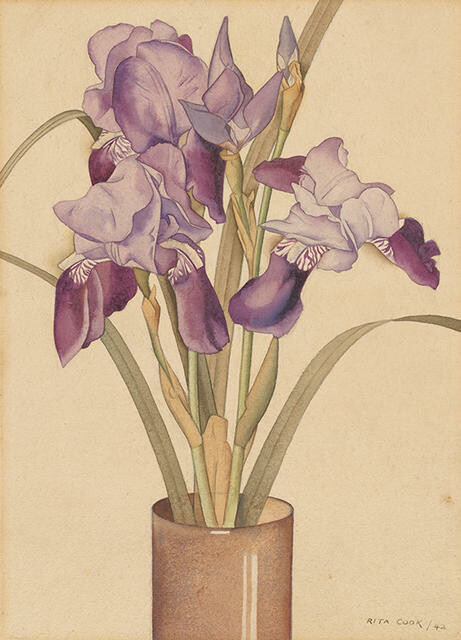

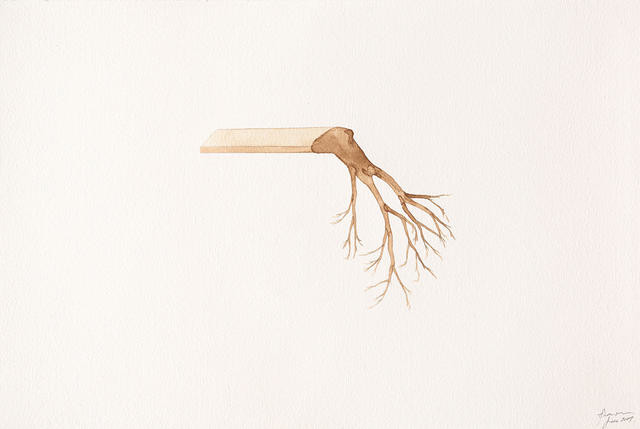

Irises

- 1942

- Watercolour

- Lawrence Baigent / Robert Erwin bequest, 2003

- 400 x 300mm

- 2003/58

Tags: flowers (plants), purple (color), still lifes, vases

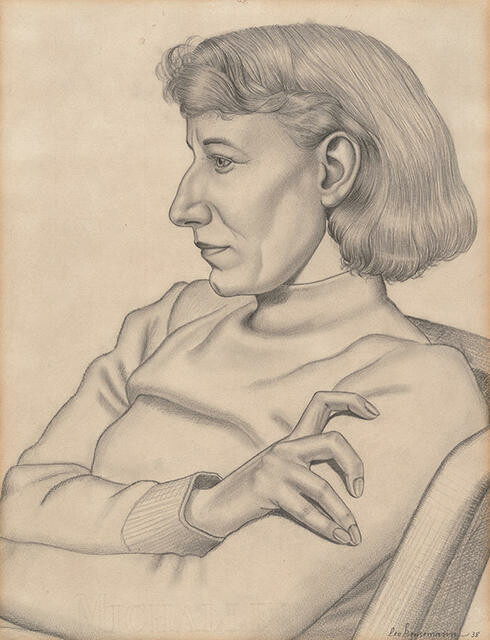

A keen gardener, Rita Angus painted flower studies throughout her career. During the 1940s in particular she painted some very elegant and botanically exact works such as Irises. Her flower studies allude to the symbolic meanings of flowers, a common feature of Medieval and Renaissance art. She often included flowers in her portraits to represent their associated meanings. The iris stands for faith, wisdom and hope. Angus was born in Hastings. She studied at the Canterbury College School of Art from 1927 to 1933. In 1930 she married Canterbury artist Alfred Cook and, although they separated in 1934, she signed her work ‘Rita Cook’ until 1941. She lived and worked in Christchurch until 1955 when she moved to Wellington. In 1958 Angus was awarded an Association of New Zealand Art Societies Fellowship, which allowed her to visit England and Europe.