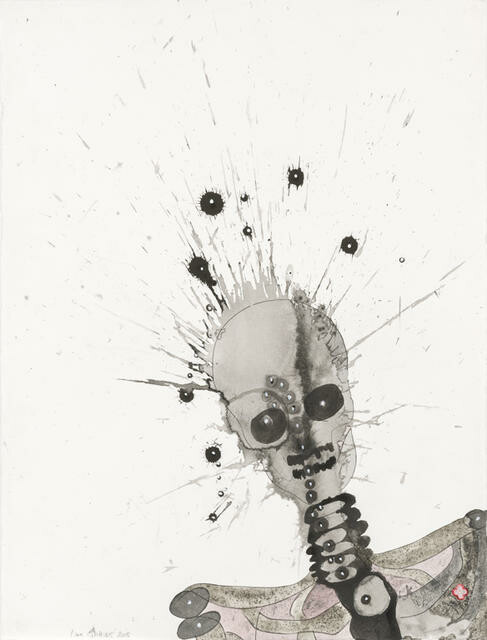

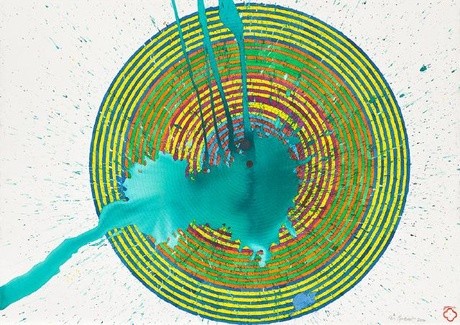

Max Gimblett

Aotearoa New Zealand, b.1935

Disasters of War - 14 - Electrocution

- 2005

- Pencil, ink, acrylic polymer, mica / Lanaquarelle Paper. France

- The Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Gift, 2011

- 756 x 572mm

- 2011/040

Tags: monochrome, quatrefoils, skeleton and skeleton components, skulls