Kupu Whakataki

Foreword

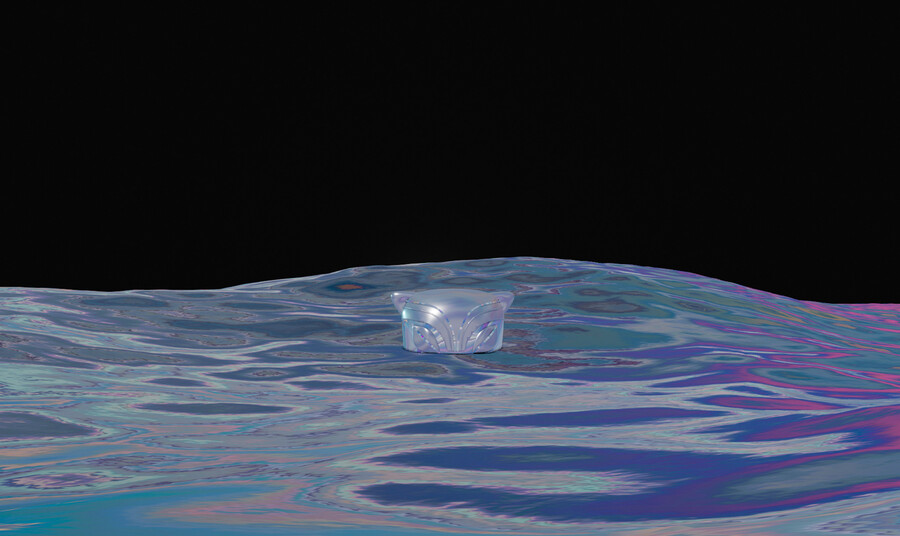

Kahurangiariki Smith Ride or Die (still) 2024. Digital animation. Courtesy of the artist

Tēnei te mihi ki te māreikura kua whetūrangihia i tēnei tau. Nā tōna mahi, nā tōna āwhina, nā tōna kaha, ka puāwai te kākano o tēnei kaupapa. Moe mai rā, Whaea Robyn.

Haere, haere, haere atu rā, he taniwha hikuroa.

Starting points are always difficult to reckon with. Inspired by Indigenous artists, academics, activists and storytellers, I’ve written previously about the traps so-called ‘beginnings’ set for us, have lectured students about the importance of asking “but what about before that?”, have revelled in the way my favourite artists draw our attention to what lies beneath these points, these moments in time. I begin here because I don’t quite know how to start this introduction and don’t really know how to talk about the exhibition’s origins in the right way. I start here because I see the exhibition Whāia te Taniwha and this accompanying edition of Bulletin as part of a longer, ongoing kōrero not only about taniwha and what they mean to us, but about the power and potentiality of the stories, knowledge, activism and artworks of takata whenua. These artworks and texts are all those things and more at the same time. A bit like taniwha, eh? In defiance of easy categorisation. Multiple things at once.

Here is a possible starting point. I met Chloe Cull in a reo Māori class almost four years ago. I had recently found out that my colleague Madi Williams and I were successful (much to our surprise) in receiving a Marsden Fast Start Grant from the Royal Society – Te Apārangi (Fast Start – another beginning) to work on a research project about taniwha: to kōrero with people around Aotearoa, delve into the archives, and look at representations of our whanauka in art, literature, the media and court evidence amongst other sources. I was trying my best to relay all this to Chloe in te reo, my sentences full of hapa... and it was there that our collective dreaming toward a taniwha exhibition began. And now, with the help of so many artists, storytellers, reo champions, technicians, editors and administrators, after lots of kōrero, email exchanges, admin, angst, laughs, freak-outs, existential crises, challenges, beautiful accidents, tohu and tribulation (and everything in between) – kei konei tātou: we get to be part of this celebration of knowledge and mystery, which has the strength of ancestral narrative and relationships and the knowledge of takata whenua at its heart.

Whaea Robyn Kahukiwa’s pukapuka Taniwha is perhaps where all this really begins for me; many of us were introduced to taniwha whanauka through the journey depicted within the pages of this taoka and many of us have grown to see the conflicting worldviews present in that story continually reflected in Aotearoa society. (That Government-led Marsden grant I mentioned earlier is no longer available for those of us working in humanities, within which Māori and Indigenous studies, history, literature and art history sit – make of that what you will.) This edition of Bulletin, this exhibition, doesn’t exist without Whaea Robyn. Taniwha and her wider body of work continue to inspire and drive this kaupapa in multiple ways and multiple directions. It is my hope that the exhibition honours the ara she has paved for us.

The opportunity to be guest editor of this magazine was another starting point (and another big learning curve) – but if you are going to dip one big toe into the curation pool I reckon you may as well put the other one in the editing deep end. This has been a chance to ask just some of the storytellers I love for their take on taniwha and, despite my ambiguous request and rather wide parameters, the tūhono within the mahi gathered here and the works in the exhibition are evident: personal reflections, divergences and intersections, whakapapa, tūpuna narratives, sass, sustenance, questioning, challenge, exchange, community, resistance, reckoning. Above all, the permanence of taniwha is affirmed, and they are portrayed as vibrant sources of guidance and inspiration. My sincerest thanks to the writers, artists and writer-artists who have contributed to this edition, to their whānau and hapori too.

Conclusions are maybe just as difficult as starting points. The exhibition may be open now and the magazine in print, but it’s really neither the beginning nor the end of anything. Our research kaupapa goes on and so too do the challenges and changes. As we continue the haereka though, we draw strength and inspiration from the narratives we’ve been privileged to spend so much time with, and we’ll attempt to navigate ngā piki me ngā heke with the vibrant whetū and whakaaro our tūpuna and our storytellers have so generously provided us with.

E rere ana taku mihi ki a koutou katoa.