Capturing the Airs

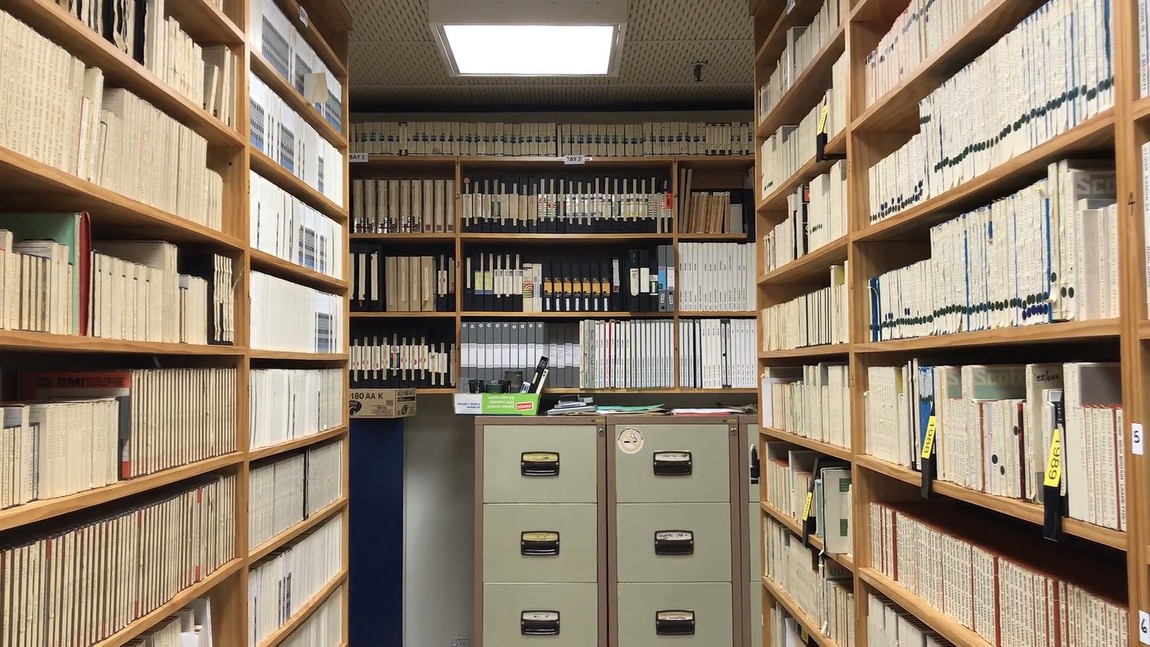

Tape covers in the Archive of Māori and Pacific Sound, University of Auckland. Photo: Huni Mancini

In the archive there is a stillness, an air of silence animated by the low hum of electronics: servers buzzing, computer screens flickering, wires, old analogue equipment. I load an audio file into a software program with a few clicks of the mouse. Its waveform unfurls on my screen, a horizontal axis of blue lines accentuated by vertical peaks and troughs, rendering the singing breath and its energetic highs and lows. I press play and ambient sounds flood the speakers. The magnetic tape hisses, jumps and crackles as it winds along, the swell of laughter, singing voices, traffic passing by – inflections of a bygone era. I’m transported to the memory of learning mā'ulu'ulu, a Tongan group dance, as a young girl. After church on Sundays, in the middle of winter, we would pack into the cold hall for rehearsal, kept warm by the movement of bodies swaying together.

The boundary of the imagination stretches back and forth like the tide, untethered to concrete reality. There’s a fluidity that shapes our remembering; the past touches the present, enfolding us in its soft, close embrace.

Sound is a conduit, a connector of memories, beings, generations. Not unlike the vā – the space between all things – sound is communicative in that it allows us to understand each other. Yet sound is also out of reach, beyond our grasp, because it does not last. When a sound is created it reverberates in the air for a while and, unless it’s recorded, it’s gone again.

The sound recording does not discriminate; it is universal, and it holds us accountable. It remembers not just important events, but ordinary ones too. Ambient soundscapes are filled with laughter and gossip, children playing, crickets chirping and rain falling. These are the sounds that make up the present moment but are easily forgotten in the reordering of our memories.

Such moments remind me of afternoons spent in my aunt’s backyard, hearing the laughter of fanau, the smell of food. The recording transmits knowledge of these moments, drawing them into the present. Like a photograph traces the contours of the face, or a letter traces the movement of the hand, a recording traces the rhythm and flow of the breath. It casts you into the memory of being together, sharing space.

Oceanic peoples have used sound to preserve a record of the past since time immemorial. Oral traditions – story- telling, genealogy, song, dance and countless others – are our methods of recording, arranging and describing the past. They are our ‘written documents’. Each composition is interlaced with a wealth of meaning, poetic language and mnemonics, strung together like flowers on a garland. But oral histories are often considered unreliable by scholars who favour the written word. As a result, our voices have been left out, erased and rewritten by the dominant history.

The Archive of Māori and Pacific Sound was established in 1970 to preserve vulnerable heritage from throughout the Pacific. At the time, decolonisation had already begun in Oceania, with a number of Pacific nations achieving independence by transitioning from European colonial rule back to full independence. Yet there was a growing concern that many of the older traditions had already vanished or were undergoing rapid change as a result of increasing urbanisation and Westernisation. It was also a period of great advancement in technology, which gave researchers and communities the ability to record the way oral traditions were being sung, performed, and expressed – “capturing the airs” as Sir Apirana Ngata referred to it.1

Archive of Māori and Pacific Sound, University of Auckland. Photo: Huni Mancini

The archive dates as far back as 1910, and spans the full range of audio formats from then until now. Each format has its own materiality and characteristics. Digital preservation is the latest iteration in a long line of formats, each one designed to outlive those that came before.

One of our earliest collections is the Dominion Museum Ethnological Expedition wax cylinders, recorded between 1919 and 1923. The expeditions were initiated by Sir Apirana Ngata and Te Rangihīroa (Sir Peter Buck), who had the foresight to use the cutting-edge technology of the time to capture ancestral knowledge that was feared to be fast disappearing. It was the first project of its kind. Recording iwi and hapū around the North Island they captured knowledge of a range of fishing techniques, art forms like weaving, kōwhaiwhai, kapa haka, mōteatea, ancestral rituals and everyday life in the communities they visited.2

Since that time, an unknown number of the original wax cylinders have perished. Incredibly fragile and prone to melting, shattering and erosion after each listen, the cylinders were preserved on reel-to-reel tapes by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in the 1970s. The preservation masters were acquired by the archive and are the last full set of audio that remains.

When listening to these recordings, the voices of tūpuna emerge like waves across generations, across time itself. They sound distant, almost haunting, their voices engulfed by an interface of abstract distortion – crackling, scratching and pulsating, symptoms of the wax deteriorating. The debris of technical decay has a rhythm of its own. It’s the sound of a medium being pushed to its limit, preserving the past and breaking down with it. This is an exchange between past and present that we hear more often than we realise.

Huni dancing the tau'olunga at her uncle’s ordination in Suva, Fiji. Courtesy of Huni Mancini

Archive of Māori and Pacific Sound, University of Auckland. Photo: Huni Mancini

Being raised in the diaspora, I wasn’t always surrounded by the songs and stories of my people, but rather TV, radio and the internet. I encountered music in mechanical ways: on CDs and cassettes or downloading files online, taking many painstaking hours over clunky dial-up connection. I was from a generation of young people who were more accustomed to the sound of European words and songs, the static of the television, the forms of silence and forgetting that ebb and flow over memories.

In the archive I’ve been able to reclaim some of my songs and stories. The Kingdom of Tonga collection made by anthropologists Wendy Pond and Garth Rogers holds some of the few sources of information about Niuatoputapu, the island in the northernmost region of Tonga that my grandfather was from, but spoke little about. One recording from the collection, a tau'a'alo, was composed by an old chief Loketi Lapuka and performed at a faikava gathering in Hihifo, Niuatoputapu 1969. The tau'a'alo is an ancient song, sung while paddling to maintain rhythm and synchronicity. When it was translated by Pond and collaborator Tupou Posesi Fanua, they recognised that there were two levels of meaning to its complex lyrics.

Fie tau ē pea fokotu'u 'Alu 'o tau 'I Futuna tu'u

Kae tuku 'a Niua ni ke toka

Want to fight? Then stand up

Go and fight in Futuna. Stand up!

But leave Niua in peace

Leaving Niua to be the loser.

These opening lines convey the use of heliaki, the Tongan art of metaphor, to celebrate the heroic eighteenth-century history of Niuatoputapu. Further along the nickname “Niua- teke-vaka” (Niua-which-repels boats) is used. This comes from a time when the island’s governing Mā'atu chiefs had become so powerful they were able to maintain political autonomy from Tongan rule.

But the translators found Lapuka was also commenting on the generation of younger people of the twentieth century who were leaving the island to seek work and status in Tongatapu, “leaving Niua to be the loser”. It’s a window into the helpless condition of modern-day Niuatoputapu according to Lapuka; a land without leadership, living in the illusion of its past glory.3

Archive of Māori and Pacific Sound,

University of Auckland. Photo: Huni Mancini

Seeing through Lapuka’s lens has a reparative effect for me, connecting me to a part of my own story that I had not known, a story that was made silent or absent by forces much bigger than myself.

The past is always getting away from us. It’s a distance that expands as we face away towards the illusory, impossible horizon. Yet it catches up with us in unexpected ways. Not in the way we’d like to think – not a simple projection forward – but rather the way bodies, circuits and connections take unpredictable and counterintuitive forms.

The story of the past is never done; it’s always forming and being formed by us. It’s a tapestry woven of elements that alternate between what is told and untold, what’s visible and the weight of what’s left unsaid; what you thought you knew but now see through a different lens. This balance creates a tension that shapes you.

How might the archive hold these distances alongside the intimacies? How might they be strung together like words in a song, like flowers on a garland, or recordings on a ribbon of magnetic tape? When lifted up they display the wholeness of bodies, adorning the full weight of our histories.

Our oral traditions were designed with this understanding in mind, in the way they were meant to be embodied by us, to be living, breathing reminders. Through forms of daydreaming, storytelling, the ecstasies of art and music, the poetic intricacies of language. Forms of ‘leaving’ are not the opposite of authentic presence, but forms of fluidity that shape the way we remember.