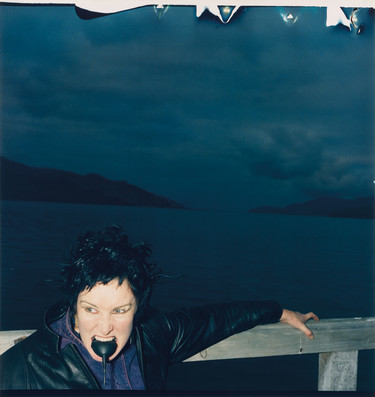

Margaret Dawson Consuming the Veneer 1987. C-type print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, 2022, in celebration of their 50th Anniversary 1971–2021

Mediating Reality

In the late 1980s, a significant shift for photography in Aotearoa New Zealand was identified in two art publications. The essays and images in these books showed how artists were utilising new strategies, breaking away from the prevailing documentary photography tradition that was, and still is, widespread in Aotearoa. Six Women Photographers (1986) was edited by artists Merylyn Tweedie and Rhondda Bosworth for Photoforum; and Imposing Narratives: Beyond the Documentary in Recent New Zealand Photography (1989) was the catalogue for an exhibition curated by Gregory Burke for City Gallery Wellington. The artists included in both publications questioned in various ways the assumptions and rules of image making, manipulating the media and making a political move from the standpoint of taking a photograph, to making one. No longer was a photograph considered a truthful representation of reality. Instead, photography was seen as a product of, and a participant in, current social and cultural values.

Curator and writer Athol McCredie has written about the beginnings of contemporary photography in New Zealand of the 1960s and 1970s as a turn towards personal documentary photography.1 In the 1980s, however, with the introduction of postmodern and feminist practices and ideas, the construction and subjectivity of photography became paramount. In the preface to Six Women Photographers, Tweedie wrote:

[The] photograph can be treated as a fact in its actuality and historic specificity or it can be treated as a fictive element where the fact is but the reason of fiction and they [the photographers] make their own statements by coming to terms with the culture they share and using the materials on hand that is their bodies their selves and their lives they establish a means of understanding that culture and their position within it.2

Gregory Burke also saw that the camera activates a fiction and described the subversive role of photography at the time, concluding that, “By bringing us back to the surface, these images seek to speak of and through the play of difference.”3

Women photographers in particular were keen to explore alternative methods of representation and to expose the constructed nature of images: to defy the male gaze, to reveal the frame and to undermine the patriarchal societal expectations embodied in a photograph. While we now take for granted that photos are layered, filtered, photoshopped and fabricated into images that can circulate widely in our digital culture, it is important to recognise this awareness as a new phenomenon. The photographers of the 1970s and 1980s were a disruptive and energising force, making work that anticipated our current visual paradigm rather than simply propagating the story of social documentary photography. As curator Sandy Callister has written, they were:

…harbingers of a new way of both seeing and being. Experimenting with the new media of their time, the artists foreshadow the way in which our identities are currently being filtered by technologies that mediate our desires and inner thoughts. Today, more than ever, reality and consciousness are not only reflected, but produced by images and screens.4

A number of artists who worked during this time to destabilise traditional photographic concepts and techniques were based in Ōtautahi Christchurch and the Gallery has recently acquired examples of their work through a generous donation from the Friends of the Gallery. Our exhibition Perilous: Unheard Stories from the Collection includes a selection of these photographs, which utilise different strategies to mediate reality.

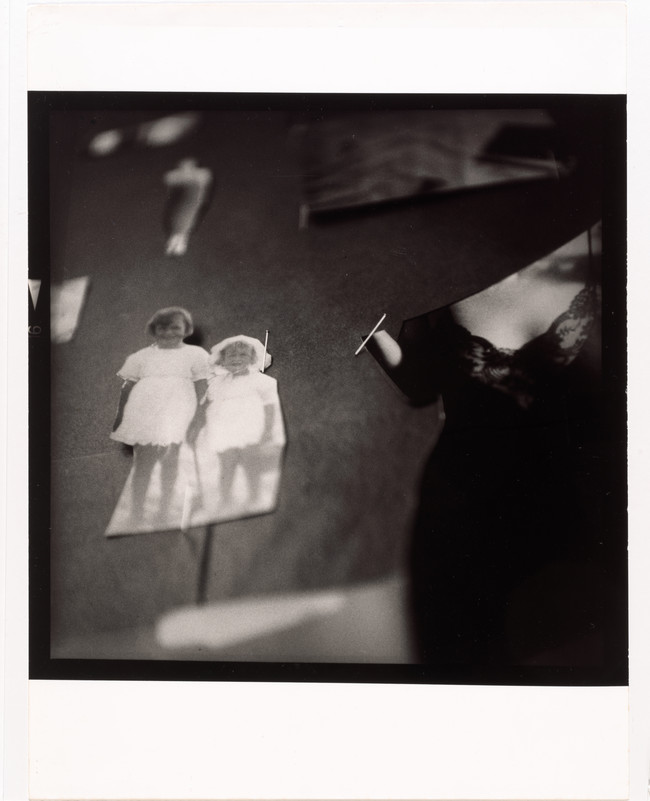

Rhondda Bosworth Memory Vista 1989. Silver gelatin print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2021

Born in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in 1944, Rhondda Bosworth studied painting at the University of Canterbury’s Ilam School of Fine Arts and lived in Christchurch for several years before returning to Auckland. Bosworth challenged the apparent rules of photography, the dominance of the male gaze and Henri Cartier-Bresson’s notion of the decisive moment. She is known for a distinct visual language of intimate, high-contrast black and white photographs featuring content that is intense, disruptive and disarming. For example, in her series of self-portraits from 1985 depicting herself in a room empty except for a wire-frame single bed, Bosworth used a wide-angle lens at a high viewpoint to distort the edges of the photographs, generating a sense of claustrophobia and unease.

Focusing mainly on the portrait as still-life, often using her own body, Bosworth incorporated text, re-photographed existing images, and used movement, test strips, collage and reproduction as strategies to create powerful images that retain ambiguity or mystery. By layering her own photographs into narratives that resist a simple explanation, she translates difficult stories or relationships into images that viewers can relate to their own emotional memories. This can be seen in Memory Vista (1989) where the artist has cut out photographs, collaged the figures and then re- photographed the scene, disconnecting the subjects from their initial context and transplanting them to an associative landscape that suggests any number of potential relationships. The result is a deftly manufactured and evocative image Marie Shannon (b. 1960) reinforces Bosworth’s view that self-portraiture is a creative fiction. Speaking in Six Women Photographers, she states:

I do not see these pictures as conventional self- portraits no matter how much of myself is shown in them. They are ‘pictures of myself’ or ‘pictures that include myself’ but they are not limited to portraiture. I think of these photographs as narrative pictures. To me they are more than visual images. I would like them to be ‘read’ – backwards and forwards, up and down, with the same sort of build-up of detail you get when you are reading a text.5

Marie Shannon St Patrick’s Day Manicure, The Wearing of the Green 1986. Silver gelatin print, selenium toned Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, 2022, in celebration of their 50th Anniversary 1971–2021

These views on self-portraiture are taken to the extreme in the work of a photographer who has lived in Christchurch since the late 1970s, Margaret Dawson (b.1950). Her work uses photography as a means to explore identity and gender roles through carefully constructed images of herself and others, usually made in series. In Consuming the Veneer and The Price is Too Great (both from her 1987 Marg n. l. Persona series) we see Dawson’s distinctive use of her own body in different settings or characters as a way to show the mutability of the self and fluidity of representation. First, a woman with a short, punk haircut bites down hard on the auto-release cable for the camera. Snap. In the background we can just make out the headlands of Whakaraupō Lyttleton Harbour, as seen from the Governors Bay wharf. Then in The Price is Too Great, a woman is bent over retrieving scraps from the street. Though they are in fact the same woman – herself – she is unrecognisable. Dawson suggests that those images we see of others are similarly fleeting and unreliable; that we can all be seen in many different lights and perspectives.

Innovative social documentary was made in conversation with these more obviously performed and constructed works. Christchurch-based artist Jane Zusters (née Arbuckle, b. 1951) is well known for her vibrant 1980s paintings, yet has worked across painting, photography and ceramics. Her photographs from the late 1970s capture her bohemian lifestyle and friends in Christchurch, offering new perspectives on gender and identity at this time. The rich colour palette of her analogue prints emphasise an emotional warmth and her compositions are exact, making strong statements on issues of representation.

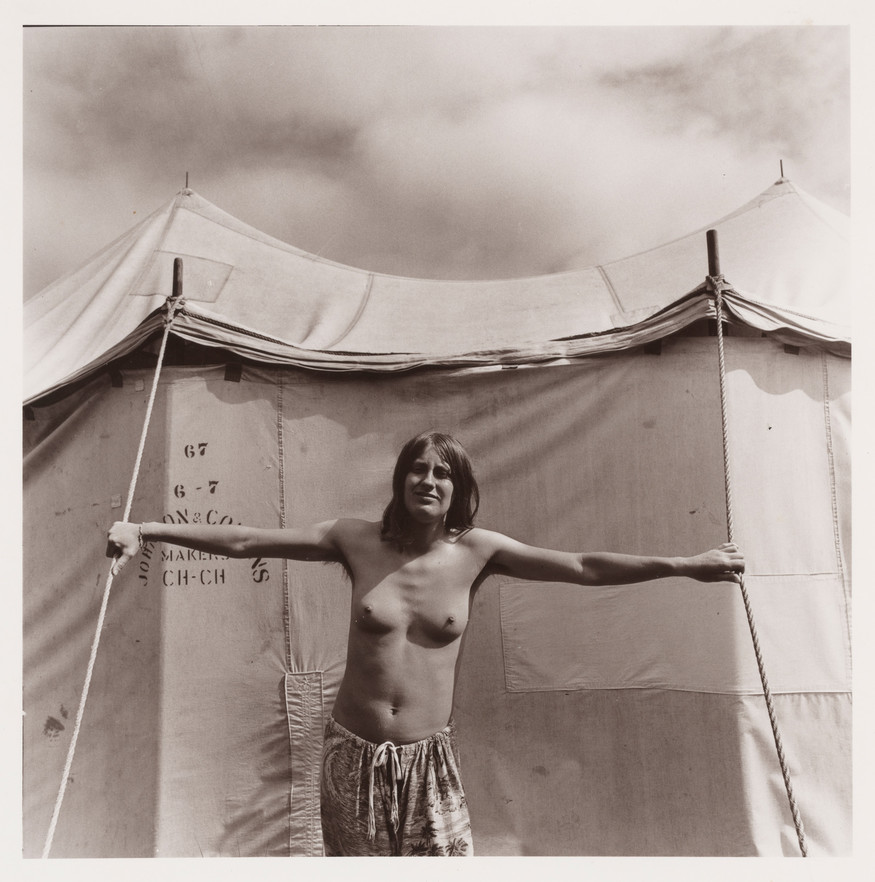

Zusters created several images that are important for Aotearoa’s history, such as the four-part work Portrait of a Woman Marrying Herself (1978), or the photograph of a 1975 Christchurch pro-choice protest featuring a placard reading ‘This Woman Died I Care’ – a sign that was later turned into a powerful painting by Allie Eagle (1949–2022). In Zusters’ photographs we see artists gathering for a life- drawing session at her house in North Beach, their coffee cups resting on woven mats as they sketch; a topless friend, Margaret Flaws, casually holding the guy ropes of a tent in Punakaiki, her arms outstretched like a crucifix; and a truncated nude figure in the pool, staying afloat by curling her toes under the handrail. Tender details such as these give us a sense of loving relationships and a supportive community, despite the conservatism that also existed in Christchurch.

Jane Zusters Margaret Flaws at Punakaiki 1978. Unique silver gelatin print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, gift of the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, 2022, in celebration of their 50th Anniversary 1971–2021

Fiona Clark (b. 1954) is one of Aotearoa’s most important social documentary photographers. She is known for ensuring the agency of her subjects, incorporating their words into her work and building strong ongoing relationships, particularly within the LGBTQI+ community. In the 1970s and 1980s Clark photographed the gay and drag scene on Karangahape Road and in the clubs Mojo’s and Las Vegas Club. The Gallery has acquired two photographs from this era: Diana and Sheila at Mojo’s, Auckland (1975) and Diana and Perry at Miss NZ Drag Queen Ball (1975). When Clark exhibited photographs similar to these in 1975 as part of The Active Eye, audiences were shocked. Today, they give us valuable insights into that time from the perspective of those involved.

Two further photographs by Clark that are new to the collection are of Chrissy Witoko (1944–2002), owner of the Evergreen Coffee Lounge on Vivian Street in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington. The Evergreen was a popular late-night entertainment establishment and a safe, accepting environment for the queer community from the 1980s to mid-1990s. Chrissy is pictured in her apartment upstairs from the Evergreen in 1989 and just out of shot is the throne gifted to her when she was crowned ‘Queen Christine of Wellington’ on her 50th birthday. In the second image, from 2001, Chrissy is shown with family – an important aspect of her life. Clark says:

My intent is to give people a voice. The photos say, “I am who I am. I’m here. I’m part of your world and I’m going to stay.” What’s so powerful is the participant’s gaze and directness, but there’s also a huge sadness. You can see the struggle it takes to keep that personal momentum going. I hope these photos make you feel the human connection we all feel when we look at another person. It’s the thread that binds us.6

Fiona Clark Diana and Sheila at Mojo’s, Auckland 1975. Durst Lambda print from digital master. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, 2022, in celebration of their 50th Anniversary 1971–2021

The history of photography is more diverse and disruptive than it is sometimes portrayed. There are many photographers whose work goes beyond documentary, including Minerva Betts, Janet Bayley, Megan Jenkinson, Fiona Pardington, Christine Webster, Alexis Hunter and others too. Exhibitions like Fragments of a World: Artists Working in Film and Photography 1973–1987 curated by Callister for the Adam Art Gallery in 2015 are refreshing takes on our art history. Building up this aspect of our collection enables us to tell a broader range of stories and to show these works in relation to contemporary photographers. Looking back, it is obvious that approaches of the 1980s have been foundational for what has followed: especially the insistence on the importance of situated perspectives and interpersonal relationships; and the freedom to treat each image according to the artist’s own rules.