Memory Pictures

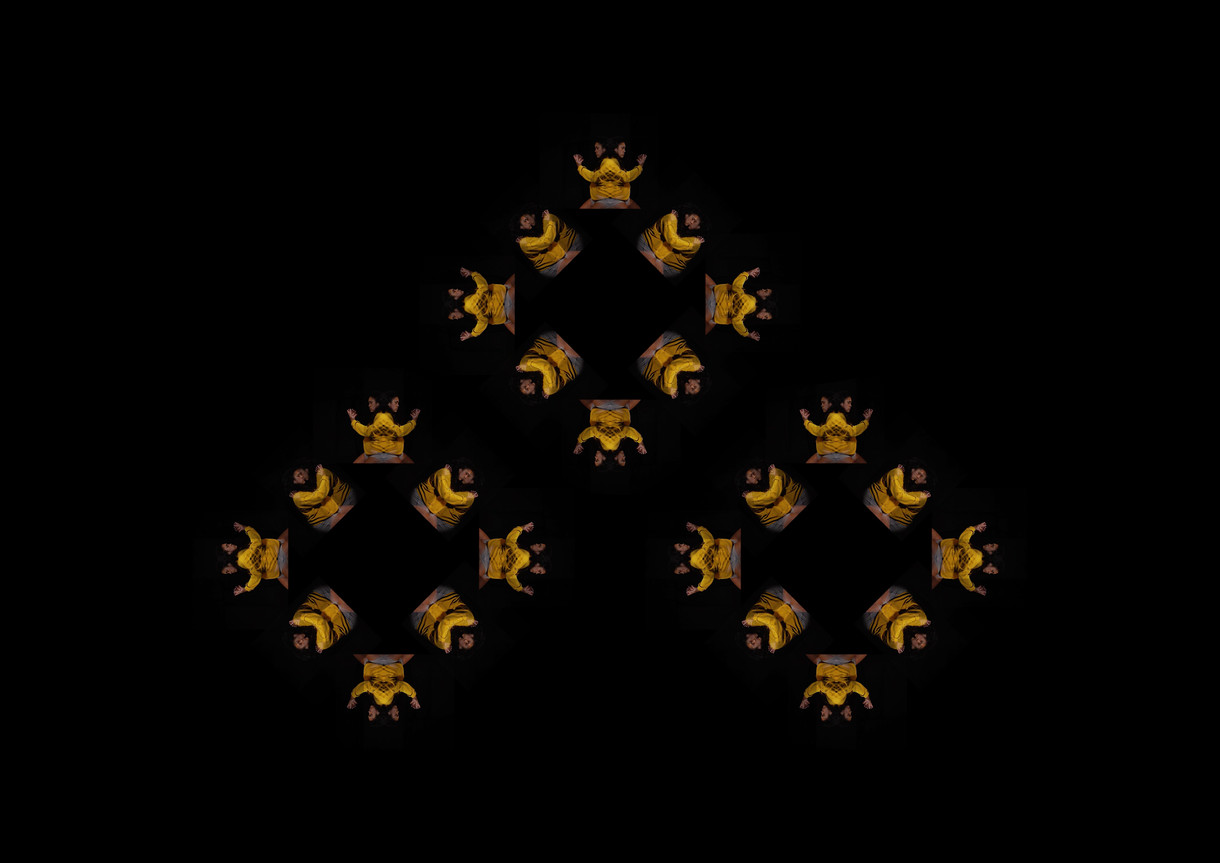

Kauri Wharewera Te Kahui o Matariki 2021. Digital animation; 7 mins, 56 secs. Commissioned by CIRCUIT Artist Film and Video Aotearoa New Zealand. Courtesy of the artist

… it suits me to take pictures on celluloid that were formerly pictures of the mind, memory pictures, pictures of the imagination …1

In 1990, Barry Barclay described film-making and the act of “taking pictures” as a kind of robbery. With film, he says, an image leaves the place where it was made “and will probably never return”. In that process, filmmakers “become custodians of other people’s spirits”. It was Barclay’s hope that new forms of engagement with the many records that have already been created – images, films, oral histories – underpinned by the “Māori knowledge of what spirit shines through” them could guide their return, to the people and places where the “held image” was taken from.2

As I was writing this, the first photograph of Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the centre of our Milky Way galaxy, was published by the Event Horizon project, an international team of more than 300 scientists and thirteen institutions. I was struck by the image’s refusal to be ‘held’. The photograph, a burning orange circular glow reminiscent of the effect created by staring at a light and then squeezing your eyes tightly closed, is an impossible vision – pieced together by a global network of telescopes that compose one large telescope larger than Earth, the gaps in their vision filled in by computer algorithms. Perfectly still, it cannot describe the noise and turbulence that defines its subject: that is an understanding it leaves for us to account for. Seen by most of us on screens no larger than a television – but more likely a cell phone – a terrifying vastness we can hardly begin to understand is reduced trillions of times over. Looking at the image as I write this, I stretch my hand over the screen, trying to cover it. It disappears behind my palm, only soft edges poking through.

In 2003, Rachael Rakena described digital space as “a new realm of the cosmos”. For Māori artists, it is “like the ocean our tupuna crossed”.

It is specifically non-land-based. It is a fluid medium through which movement, both travel and floating occurs. This space allows for relationships across terrains where the issue of identity lies not so much in geography but in the development of communities in fluid spaces that are both resonant with mythologies, whakapapa and belonging, and responsive to contemporary technologies. And, indeed, produced by them.3

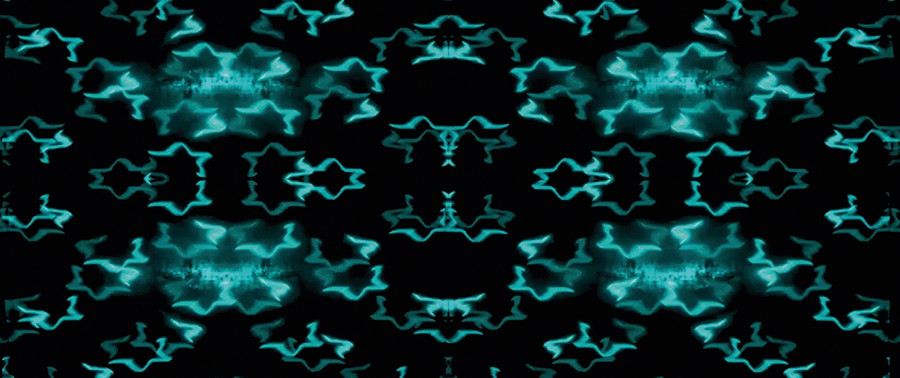

Rachael Rakena Rerehiko 2003. Multi-projection video

environment. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery

Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2004

The liquidity of digital media has been a key theme of the writing that surrounds Māori moving image artworks. Rakena’s term ‘toi rerehiko’ is a combination of rorohiko (the reo Māori word for computer, or electric brain) and rere (to flow). That flowing, or unifying, nature of water as a way of describing digital art is “not unexpected in our island nation”, argues Maree Mills in her 2009 essay ‘Pou Rewa: The Liquid Post, Māori Go Digital?’

The traversing of cyberspace outside the limitations of time is also metaphoric of the soul’s journey to Hawaiiki (our homeland) or to the realms of Rangi (our sky father) where the departed may rest and sparkle as stars.4

In part, it is the liveliness of moving image that connects it with those histories: a capacity for change and transformation. Moving image is defined by its relationship to time. What Māori artists seem to have found in it is a way of describing the passage of time that feels, paradoxically, uninhibited – stretching out beyond the linearity of the media and into an expression of time that can be “as long or short or broken or continuous” as the narrative that sustains it.5

Dr Shepard Doleman, from the Event Horizon project, described trying to see Sagittarius A* through the blur created by ionized electrons and protons in interstellar space as like “looking through shower glass”. It’s a hazy recollection: since the image was taken, the black hole has transformed thousands of times over.

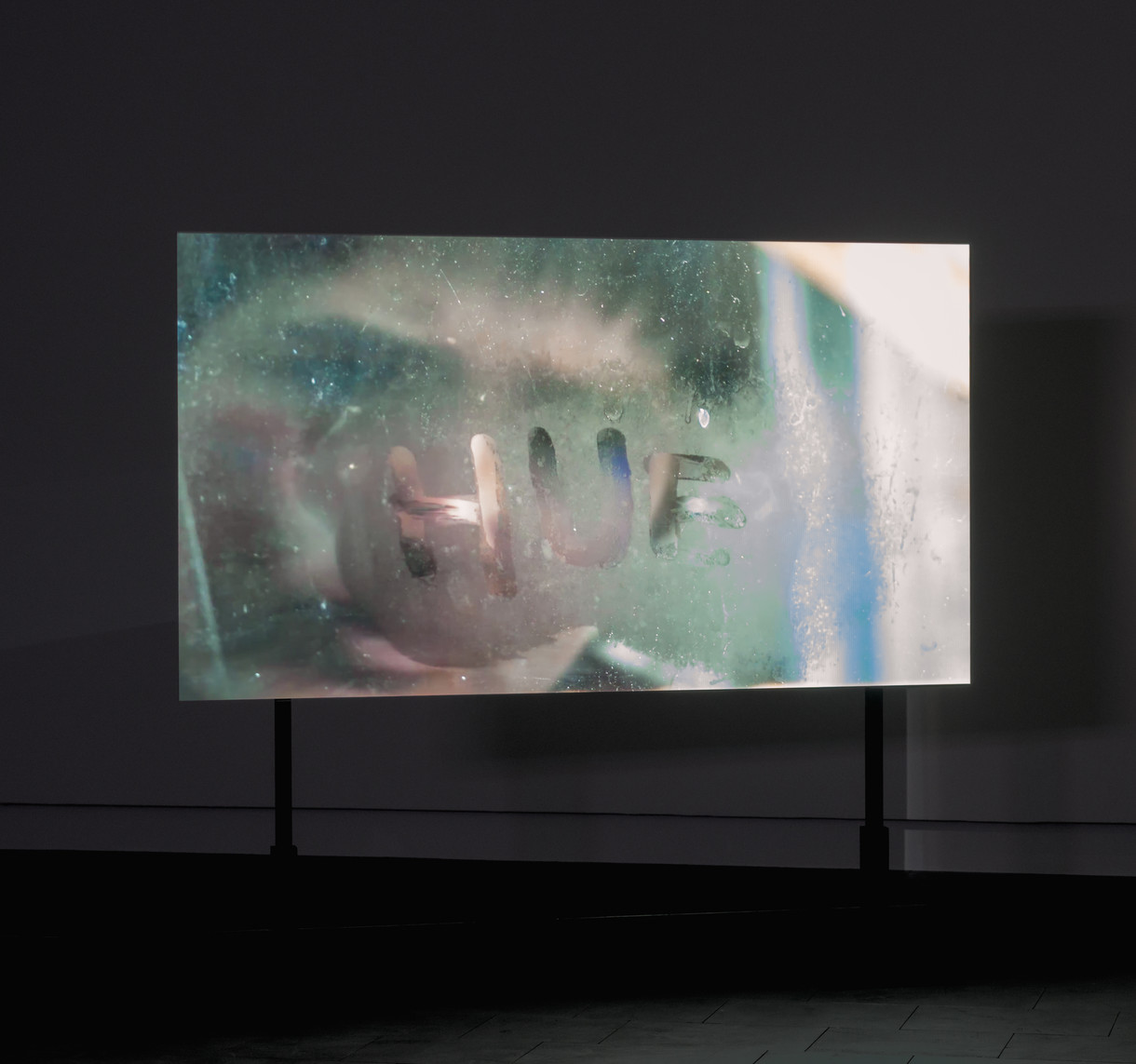

Ana Iti Trapped in a kiss 2021. Single-channel HD video. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2022

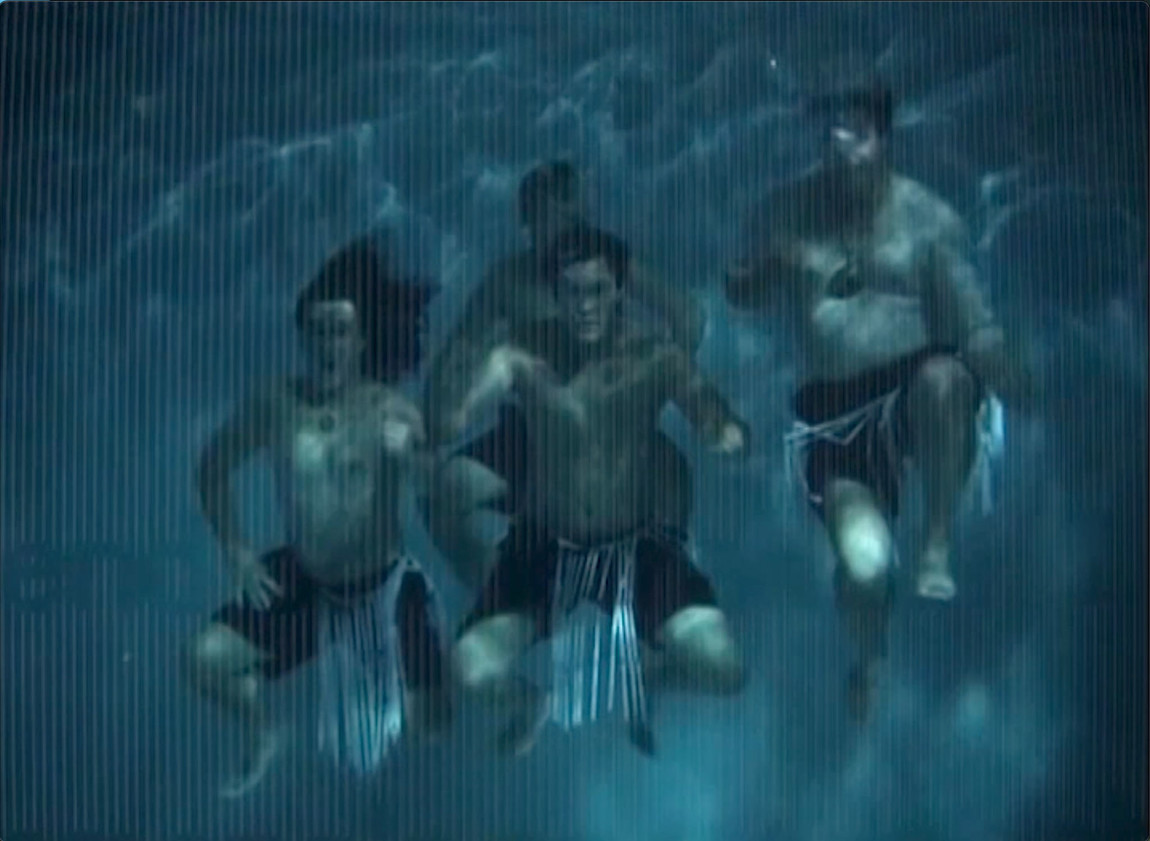

In Ana Iti’s Trapped in a kiss (2021), Iti’s warm breath collides with a cold pane of glass to form a foggy surface. Using her fingers, she writes directly on to it – the impermanent nature of her frosty page a reminder of the fickleness of memory. Talking about his work Ia ra, ia ra (rere runga, rere raro) Everyday (I fly high, I fly low) (2021) and the location where it was made – a valley that is “one of the places I call home” – Shannon Te Ao says that it sits between a real and a fictional place. Between what happens in the world and what happens in the film there are no points of convergence, where a viewer can say: this is real life. Of course, that feeling does not prevent them from saying: this feels like my life. Both Iti and Te Ao’s work seem intimately personal in the same way that a memory is only your own.6

It was the absence of a record of Māori video art that drove Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive in its various iterations at the Dowse Art Museum, Christchurch Art Gallery and Te Uru Waitakere over 2019–2021. The exhibition set out to fill a silence with noise. This impulse is telling: the lack of a historic record does not mean there is not a history. What Māori Moving Image made clear was the enormity of that absence, particularly in light of the fact that two generations of Aotearoa’s most successful, prolific and innovative artists were represented in it.

It is exciting to see Māori Moving Image continue to change and take on new forms, as it journeys around the country again. Watching Terri Te Tau’s Blue Smoke, I am reminded of how much moving image can draw on – and give new life to – familiar and unfamiliar existing material. Te Tau’s karaoke video repurposes archival footage of women doing industrial work during WWII, the lyrics to Pixie Williams’s 1949 Blue Smoke cross-stitched along the bottom, in time to the song. Te Tau’s work seems to raise the question: how far back could Māori moving image stretch? Can we push it back towards the first representations of Māori on film – and perhaps even further again, taking into account the landscapes, people and traditions that place these artworks in a far longer history?

Time changes as you approach a black hole – the closer you are, the slower it becomes. Inside, we don’t know what happens. None of the usual laws apply. In Kauri Wharewera’s Te Kahui o Matariki (2021), a series of undulating forms expand and contract to create shifting portraits of stars in the Matariki cluster: Ururangi, Matariki, Pohutakawa, Waiti, Waita, Tupua-nuku, Tupu-a-rangi, Waipunarangi, Hiwa-i-te-rangi. They are in constant motion, morphing between one shape and another, refusing to be held in place.

Shannon Te Ao Ia ra, ia ra (rere runga, rere raro) 2021. 3-channel 4K video, black and white, sound; 6 mins, 20 secs. Featuring Zen Te Hira, Heremaia Tapiata Bright

and Kurt Komene; photography by Harry Culy; production by Michael Bridgman. With Thanks to Kate Te Ao, Shaun Waugh, Creative New Zealand and Whiti o Rehua School of Art Massey University