RE: UNCOMFORTABLE SILENCE

Shiraz Sadikeen Geist 1 (detail) 2019. Cast polyurethane resin, white appliance paint, polished hand-wrought nails. Collection of the artist

In a recent essay Zadie Smith wrote of language as a “verbal container” – like all containers it allows the emergence of some ideas while limiting the possibility of others. The words and terms we choose, or those which are offered to us, “behave as containers for our ideas, necessarily shaping and determining the form of what it is we think, or think we think.”1 She is discussing writing fiction, defending the right to, and value of, drifting into other imagined bodies and taking a good look around, regardless of their likeness to our own biographical specifics. It is an uncomfortable position to hold in a cultural climate where, Smith argues, “the old – and never especially helpful – adage write what you know has morphed into something more like a threat: Stay in your lane.”

Art writing is restricted via similar channels of commonality. Distrustful of unknown tongues and distant keyboards, there is a palpable generational divide. It is a valuable thing for an artist to have peers write about their work armed with intimate and specific knowledge and perspective, but it can also fortify ideas through likeminded affirmation. In an attempt to productively disrupt this cycle, eight established writers have been asked to contribute a text to sit alongside the work of one of the eight artists included in the exhibition Uncomfortable Silence.

Broad and subjective in approach, these writers don’t all set out to gain a deep understanding of the intentions or the practice of the artist they have been paired with, but instead register a response that widens perspectives. It is an opportunity for established writers to write outside their usual modes, on work they don’t necessarily know, and for artists to see how their work reads beyond familiar discourse, in particular that of art school and artist-run spaces. For the most part, the contributing writers are a generation or two older than the artists exhibiting, and only vaguely acquainted, if at all, with the artists’ work.

The exhibition itself draws together artists whose work considers or elicits a response of discomfort. Taking this unease as a valuable – even necessary – condition for thought and understanding, the work of these eight artists inhabits the space where the familiar and recognisable slip into the unknown and problematic. If we consider the role and response of the viewer as a form of improvising on the unknown, then it is often an awkward experience, but also very much a creative one. Whilst we might find ourselves in an art gallery viewing a show that our social media data predicts we will like, an exhibition like this is not curated by an algorithm to confirm our specific world view. Some works are sure to be a baggy fit.

Several of the artists included in the exhibition make work that critiques traditionally white and male-led environments: namely the workplace and the art gallery. They lean into and appropriate the languages, tools and systems of their mediums – of advertising and interpersonal relations – and hijack middle-class consumerism. Mark Schroder’s installation catches a corporate office stagnating at the point of collapse, employing marketing techniques to consider the relationship between aspiration and disappointment, whilst Elisabeth Pointon borrows directly from work emails, literally blowing up corporate language to explore accessibility and representation. Meg Porteous’s self-portraits mimic the celebrity ‘caught’ on film, putting the tropes of surveillance and self-portraiture into play in a way that questions the authority and authenticity we have over our own image. Shiraz Sadikeen’s wall sculptures and paintings play on our expectations of the art on view in public art galleries, commandeering imagery that inspires us in a scrolling of possible images or brands, from trollface to Totenkopf, and leaving us open to uneasy gut reactions.

Like avalanches in slow motion, Clare Logan’s mutable landscapes evoke a similar uncertainty and tension between what is known and unknown. She investigates the space between the physical and psychological through painting, whilst Johanna Mechen’s lens-based practice explores the relationship between the maternal and creative experience. Mechen’s work is a beautiful – if sometimes uncomfortable – record of the fears and anxieties of parenthood. Jayden Plank’s paintings and sculpture grasp at futuristic transcendence, synthesising an investigation of the limitlessness of inner worlds and outer space. And Ammon Ngakuru’s fragile papier mâché shelter – hinting at the tiny house movement – is itself a kind of verbal container laid bare, a structure built from offered words. His rendition of a night light fashioned from a Martino Gamper Arnold Circus stool is a wry transformation of a signifier of middle-class consumerism into an object of innocence and security.

Sustaining an art practice has its performance incentives and anxieties, especially in an online context. How it is to be an artist – to negotiate a practice in balance with a professional and personal life, and to perform within that space – is never far beneath the surface. The artists presented in Uncomfortable Silence live and trade on the certainty of the uncertain, carefully upending, undermining and rewriting the scenes they find themselves in.

Jon Bywater / Shiraz Sadikeen

Shiraz Sadikeen Geist 1 2019. Cast polyurethane resin, white appliance paint, polished hand-wrought nails. Collection of the artist

Dark Patterns

The painted resin in Shiraz Sadikeen’s Geist reliefs looks a little like spat gum. Nail stabs like teethmarks, the pricks pick out mouths and eyes, making each a small white ghost that resembles the internet meme trollface. All nails have heads, of course, but these have faces too. It’s a perceptual hack that never wears off: two dots within a closed curve, and there’s a face. We can’t help it. Pinned to the wall through the eye, they could be crude, comic crucifixions. They needle me gently, grinning while I puzzle through the things I see them as.

What we can and what we can’t help is at the crux of what I find compelling about Sadikeen’s recent work. The formality of his stretched canvases (and of the repetitions between and within them in series and grids) invites careful, self-conscious contemplation; conservative, white-wall conventions brought to the fore here by the way they frame coolly abstracted, hot-button references.

The artist spells out for us that the generic figure in (In)corporeal Schema Fig.36 is a pattern for a racist toy, for example; that the swaying green mark in Zig Zag is the Arabic script for halal, familiar from Islamic dietary laws. Again, there are triggers: it’s a golliwog, I learn, and flinch. But then what? In combination, features of the zeitgeist are suggestively picked out, and art’s uses for them are drawn into question.

In user-experience design, deliberate manipulations – which, in a simple case, might steer us past not un-ticking the box to opt into the mailing list when we enter a draw – are referred to as “dark patterns”. It could be ambiguous whether opting out invalidates our entry, or perhaps the box may just be awkwardly placed. As contributors to the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in New York put it, the way we are likely to interact is predicted to exploit us, as “user value is supplanted in favor of shareholder value”2

Conditions including planetary-scale computation accelerate and intensify old ways in which our instincts are used or work against us, and the implications may be significant. Restless feelings like envy and anxiety keep us refreshing our feeds. Expressions of outrage get the most retweets. Such emotional dynamics relate suggestively to the way that reactionary and right-wing movements flourish in what Indian writer Pankaj Mishra calls “the age of anger”.3

In the quiet of the gallery, face to face with Sadikeen’s modestly-scaled works, I am aware that I am in a cultural space produced by the same globalisation of a Western secular individualism that Mishra links to Brexit and ISIS alike. Rather than any irony, my sense of a potential value still to be found in art is sharpened. Sadikeen’s work allows me to catch myself sensing my own sensitivities – the gut reactions often important to art are not allowed to seem like ends in themselves, nor things I don’t need to take responsibility for.

Stuart McKenzie / Johanna Mechen

Johanna Mechen Playdough 2019. Archival digital print on photorag. Collection of the artist

Memory and Revision – Time Taken, Time Given

I kicked myself when I lost the notes I had made on meeting Johanna Mechen at Preservatorium Cafe in Mt Cook, Wellington, to talk about her photography. I jotted down everything she said, but now that’s all gone like childhood, like tears in rain. Anything I write here is rescued from memory and open to revision.

I did write an Instagram post after leaving our meeting and returning to my parked car on Torrens Terrace, where I took a random pic of a blood-red Bridgestone Tyres shed against a deep blue sky. I wrote, “The Bridgestone Tyres company was started in 1930 in Japan by Shojiro Ishibashi. In Japanese, ishi means stone and bashi is bridge. Hence, Bridgestone. Linguistically, this is known as a ‘calque translation’ or a ‘loan translation’ – an expression adopted from one language into another in a more or less literal form. Johanna’s photography involves the re-staging and re-photographing of snapshots made years earlier of her children’s play. It struck me that that’s a kind of loan translation. But every loan needs to be paid back…”

Chance associations are where the rubber hits the road as any student of psychology or surrealism knows. It felt to me that the happenstance of Bridgestone and Mechen illuminated the effect of translation at the heart of her practice. But what exactly is being translated? Her children’s throwaway playthings are re-made as significant artefacts. These Johanna then fixes in alluring, large-format black and white images that hark back in their enigmatic formal complexity to the work of various surrealist photographers. (She cites the lives and ethics of surrealist women as artists and mothers as an influence.)

Revisioning motherhood is important for Johanna. It is part and parcel of her art. Her assurance that she has sought and been given her children’s permission and collaborative input in selecting and re-presenting moments from their past is part of the very meaning of the work. In Johanna’s photographs and video installations her children are summoned and protected through these talismanic mementoes. In her practice, mother and children can play again, even while Johanna is actively working, translating (or better, transmuting) hectic and all-too-easily devalued domestic time into culturally valued time.

When I met Johanna she gently corrected me on the pronunciation of her name, which I learned should be spoken in the German fashion. I asked about her German heritage, but in fact she has no such background, it is rather a tonal effect of changing her name as a young woman. And in Johanna’s work too, what you think you are seeing is not in fact a given reality, but reality revisioned. For example, the flowers on the cactus in Cactus Flowers (2018) are grafted from another image because for her daughter they simply worked well together – like mother and child work well together when they actively make time – and that is a value in itself.

The loan paid back is time.

Martin Patrick / Elisabeth Pointon

Elisabeth Pointon Best wishes to all users. 2020. Courtesy of the artist

Pop Problematics (or, the Customer Might Just Be Wrong)

When we see a slogan, what are we meant to do? Do we jump in a Pavlovian way to buy a product or support a propagandist notion, or might we perhaps slow down to consider the source and whether there are other ways to read such texts against themselves. Elisabeth Pointon takes forms of language we are overly familiar with today, often read as memes, on t-shirts or on merchandise, and lends them an additional twist.

The terms of our dis-engagement with the contemporary world are trailed behind airplanes, in a form of flash display which originated almost a century ago: SPECTACULAR … OUTSTANDING … BIG DEAL. The act of materialising such words in concrete, bright, large-scale actuality rather than as mere digital type upon a screen is to give them a peculiar, resonant presence. This barnstorming aeronautical flight of fancy is a logical step from earlier pieces using balloons (a reflective one emblazoned with: “It’s a big one.”) and the inflatable, dancing figures spotted around car lots.

If Pointon selectively portrays the shiny, happy surfaces of the neoliberal capitalist machine, the undertow beneath is bleak and unsettling. By working in a corporate, establishment day job – car sales – the artist has performed multiple roles as a self-described “double-agent”, with the real world inevitably leaking into her art practice. By repurposing motivational imperatives like “I care about business.” or “a result we can be proud of.”, Pointon enacts subversive strategies which also highlight contextual absurdity.

Pointon’s current project also involves an inflatable displaying the credo “GET IT RIGHT.”, a provocation on manifold levels. Once again, it’s a sample of patented business-speak, but in the creative realm it addresses the huge external pressures that emerging artists face along with their own self-imposed perfectionism. The scale of Pointon’s projects involves a tactical method of being heard and quite literally, not getting overlooked.

I realise that I am often caught in the process of seeking out irony in Pointon’s approach but I am also mindful that that could be a generational (X) preference of my own, and that to project that onto her work is another misreading. An artist of Fijian-Indian and Pākehā lineage, Elisabeth has a multicultural background. She has travelled extensively in India, and to my mind there are highly sincere, spiritually-inflected aspects to her critique, which also encompass issues relating to race, gender and class. Who has the power to make huge, outsized, general statements globally, whether in the arts, politics, entertainment or other parts of the social sphere, and why are they often so banal, so cruel? (I won’t name the so-called “leader of the free world” and his use of social media.)

To a certain extent Elisabeth seeks “goodness” – an entirely untrendy notion that has been considered by other artists, notably American painter Michelle Grabner. And she echoes the phrasing of British artist Martin Creed, best-known in Aotearoa for the large neon signs installed in Christchurch and Auckland (EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT and WHATEVER). Pointon has commented that: “the romantic figure of the artist may still prove useful in a world that is increasingly shaped by impersonal institutions”, whether academic or commercial ones. But the ongoing, ebullient and irrepressible performativity of Pointon’s practice continually intrigues, a homeopathic dose of powerful language for our often seemingly disempowered times.

Marie Shannon / Meg Porteous

Meg Porteous Self-portrait (Street) 2019. Pigment print on vinyl. Courtesy of the artist and Mossman Gallery

These Pictures Aren’t Real

In these photographs Meg Porteous’s clothes are unbranded and unremarkable – jeans, t-shirts, sweatshirts, a cap, ballet flats, sneakers. They are the uniform of the off-duty movie star just trying to hang out with her boyfriend, go shopping, meet a friend, be normal. Meg contends that this unglamorous ‘off-guard’ look is now as much a part of the way celebrities market themselves as the red-carpet glamour we expect; many of these ‘private’ moments are ones the subjects now anticipate being photographed in.

Meg has paid a photographer to be her paparazzo. Parameters have been set, and within these the photographer has control. A location is given, where the photographer will find Meg within a specific time range of an hour or so, and be able to photograph her. The photographer can use a telephoto lens if they want to stay far away, but sometimes they use a standard lens, and come closer. They don’t need to hide. She’s not trying to avoid them, but nor does she acknowledge them. (As she tells me this I start to feel nervous, reminded of hiding-games I played as a child, when friends became temporarily threatening to me.) Meg feels nervous, too, and self-conscious, when she knows the photographer is there. She moves slightly differently, more aware of herself and how she might appear from the outside. Though she is doing mundane activities in these photographs, she is performing slightly, thinking a little more than she normally would about the way she moves, while also trying to be ‘herself ’. She is the person, and she’s aware of the way the person is going to look to others. She is inside and outside herself at the same time. This is beyond the bounds of ordinary self-consciousness, as she knows that at least some of these images will be exhibited publicly.

These are self-portraits, but having multiple images of herself on the wall doesn’t make Meg feel vulnerable. She says the photographs are all fictions; they’re not real, so they don’t feel revealing. She can choose which images are shown, so she has ultimate control. At the same time, she admits that it is confronting, when she first sees the photographs, to see herself unaware, unprepared for the photograph though she knew it was going to be taken. She is doing something to herself that she wouldn’t subject another person to.

Meg describes to me a photograph that isn’t in this exhibition. It is of her and her boyfriend leaving a restaurant, and was unsatisfactory for technical reasons. However, it was also the only time she had been genuinely surprised by the photographer, forgetting during the happy and intimate dinner that they would be waiting outside. When they took the photograph, it felt wrong, and the experience was uncomfortable. As Meg describes this she wonders if it was because the photograph was too truthful – there was no performance – the picture was real.

Robin Neate / Mark Schroder

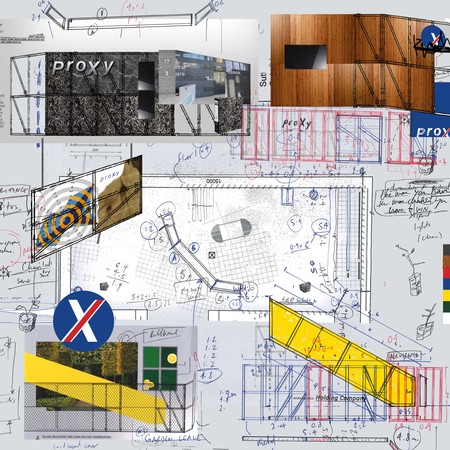

Mark Schroder Installation plan for Holding Co. 2019. Courtesy of the artist

The Aspiration and Disappointment of the External Relations Manager

Wishing well, cast a spell,

The doll’s house is ready,

Dream a little dream,

In a room within a room.

A clean white napkin,

a plate of oysters

and a bottle of white wine.

All that glitters

will be gold.

The trickle-down effect

has no affect.

We are buying

a stairway

to heaven.

Can we help it

if we are deluded?

Will you, won’t you,

will you, won’t you,

will you join the dance?

Hurry, it’s closing time.

There’s a storm coming,

Shutter the windows,

Take in the washing.

No doubt about it,

Blue skies can turn to grey.

From dawn to dusk,

There’s a revolution a day,

Break out the tumbrils.

Better call Saul.

…the fluorescent stench of excess is thick in the air. Gold-framed surfaces, motifs and dazzle language abound. The shiny façade of corporate art. Bank of the above. Plywood cologne and obscure ashtrays. Gleaming tacky litter, dirty carpet squares and a boardroom table of empty polished wood. Aspirational architectural nausea. A granite flat-screen TV flickers with cell phones. We treat your shimmering silver money like dirt. We mix business, fact, fiction and specific chance within an immersive marketing intersection between art and complex structures. Broken on the wall a distant yellow garden. Its manicured backdrop lends an obscure air…

Leftover notes,

Yesterday’s papers,

It’s a cover-up.

The bookkeeper needs a good talking to,

If you know what I mean.

Remove the filter,

Call the cleaners.

Nothing left to do,

The sun’s gone black,

Distant sirens,

The parade’s gone by.

The Titanic sails at dawn,

We are heading down the Styx,

Past the dogs of Florence.

No picture is made to endure nor to live with

but it is made to sell and

with usura,

sin against nature.

The dosshouse is full,

Wipe those tears from your eyes,

There are no coming features,

The picture show has closed.

Could there ever be a happy ending

to Franz Kafka’s America?

We can build it again.

Babel was for amateurs,

The sky is no limit,

Next stop Mars.

Les clients du bar sont partis,

Ils ont fini leurs Martinis.

…we had just finished an early evening meal, the bottles were empty and it was time to go but he wanted one more drink. I didn’t. I paid and left. Outside, I looked back through the restaurant window. It would be the last time I saw him. Sitting alone among gingham tablecloths and sanguine walls. Peering down into his half-empty glass searching for something he was never going to find. It was a warm spring evening and they were walking dogs in the park. The joggers were jogging. The swallows flying. The trees full and green with shade. The light was gradually fading and soon the day would end. Summer wasn’t far away. The days would be longer and the sun would set as it does every day only a little further to the west…

Rachel Shearer / Ammon Ngakuru

Ammon Ngakuru Night Light 2020. Carved Martino Gamper Arnold Circus stool, light. Collection of the artist

Three Works

In a world filled with accumulations of material, imbued with associations through cultural and historical processes, Ammon Ngakuru’s work gives pause amid constant reconfiguration. Night Light features Martino Gamper’s Arnold Circus stool. Originally designed in 2006 to provide public seating for events at a rejuvenated Arnold Circus in London’s East End, it has become a ubiquitous objectified form of cultural capital (aided by the stool also being manufactured in Aotearoa New Zealand). Its form is associated with a particular strata of society whose members recognise and embellish their homes with ‘good design’. This extends to an institutional arts context where it regularly furnishes dealer galleries and public art reading rooms.

With Ngakuru’s playful intervention, Gamper’s stool becomes a delivery mechanism associated with the wondrous and childlike activity of contemplating stars silhouetted on the ceiling. Night Light’s gentle critique of the emblems of middle-class consumerism at the same time signals the artist’s uncomfortable complicity. This he makes tolerable by subverting its function into the innocence and magic of a night light. Ngakuru shifts the focus away from the responsibility that comes with objects that designate status to the relief of disappearing, as a spectator, safe under a make-believe sheltering universe. Shelter of sorts is also offered in The Ordinary (Tiny House) – a papier mâché corrugated roof balanced on dropper bottles of a skincare product often used by the artist. The title references both the brand of skincare product (“Supercharged with a high concentration of two ‘next generation retinoids’…”) and the tiny house, familiar as a contemporary response to housing issues ranging from energy efficiency and land scarcity to financial restrictions. The roof of this tiny house is formed out of an accumulation of newsprint media images and text. Faith is placed in bottles of liquid imbued with powers of rejuvenation to support this fragile structure. A structure that carries the weight of noise emitting from the conflux of information while at the same time offering a tenuous lo-fi buffer against the outside world.

The third work references the everyday (literally) in a series of paintings titled Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday. Within this sequence Ngakuru indicates how he compartmentalises his time, visualised as landscapes of modular shapes and nuances of colour and texture. Souvenirs from movements within these representations are attached to the canvas, taking us from the imagined shapes of organised time to tangible three-dimensional encounters and processes – the shiny reflective inside of a chocolate wrapper, Mexican daisies and clover flowers collected during daily work as a gardener. The infinite looms behind and within Ngakuru’s mapping and memorialising of his movements. Here, time is a continuous unfolding in which past, present and future permeate one another rather than forming a linear flow. The arrangement of the shapes of ‘time spent’ is a delicate and constantly shifting structure, seeking to hold its own within the capitalist market forces that dictate our experiences and actions, and the eternal unfolding events of the universe.

p. mule / Jayden Plank

Jayden Plank Obelisk of Alien Warfare 2019. Plywood, MDF, aluminium, raku clay, pink Sculpey clay, automotive paint, glitter. Collection of the artist

Psychedelic Wasteland

The artist, by their very agency in the process of acting-out, creates a social space for the viewer in which to stand. The social space that I, the reader, am positioned in is the interface of my laptop. The images are flattened and lack a sense of materiality. I look to other social spaces that Jayden Plank may have occupied to engage with the broader community. His Elam School of Fine Arts work aligns his practice with Arthur C. Clarke and brings to mind notions of dimensions outside this 3D reality.4 I digress to surfing Clarke’s lesser-known science-fiction writings, finding a short story collection that warrants my further attention, Of Time and Stars.5 Here, in The Nine Billion Names of God (1953),6 Clarke writes of a lamasery where the monks upgrade their compilation of the names of God by systematic permutation utilising a Mark V computer. My viewing Plank’s work from a digital screen seems in some sense similar.

I note that Plank incorporates Day-Glo colours. Day-Glo paints have a significant history and are part of Plank’s conceptual methodology, referencing ‘psychedelic’, as coined by psychologist H. Osmond meaning ‘mind manifesting’. By that definition, all artistic efforts to depict the inner world of the psyche can be considered psychedelic. I reach for my copy of Leary, Metzner and Alpert’s The Psychedelic Experience (1964),7 recounting their PhD experiments with non-ordinary states of consciousness and LSD, their hopes set on radical inquiry. Does Plank similarly identify with psychedelics through the Tibetan Book of the Dead? The First Bardo Instructions read: “O (name of voyager) The time has come for you to seek new levels of reality. Your ego and the (name) game are about to cease. … In the ego-free state, wherein all things are like the void and cloudless sky, And the naked spotless intellect is like a transparent vacuum; At this moment know yourself and abide in that state.”8

Does Plank signal an interest in these disjunctions and visionary vistas of egoless states? Is he aligning himself on a more pragmatic level with the 1930s investigation of fluorescence that used black light to identify naturally occurring fluorescent compounds, and hit first upon Murine eye wash? As such, do Day-Glo paints act as Plank’s portal to not only the sixties extraordinary states of consciousness, but also to current research that increasingly recognises that hallucinogens such as magic mushrooms, LSD and MDMA can, under the right circumstances, treat depression, anxiety and other mental and physical health issues? Both terrains leave Plank well positioned within explorative fields of conjecture and refutation alluding to the potentialities of sensory input and ego dissolution: ‘Vision 5: The Vibratory Waves of External Unity… the quagmire of worldly existence?’9

Gwynneth Porter / Clare Logan

Clare Logan There opened a brightening gap 2019/20. Oil on board. Courtesy of the artist and City Art Depot, Christchurch

Summon Something

The light flares in the deep blackness like the coming of a new world, a new reality, an unknown. It destabilises and promises reorganisation, making us all adolescents, minors. Tenants. There are surges of flowing material forced between areas of hardness. Masses that have tumbled down from mountains, and mountains themselves, abstract enough to be metaphysical. The light stands proud from the dark as another form of intensity, and it is not clear what forms of engulfment will take place. Whether they will be positive or negative seems a clumsily anthropocentric consideration.

There is more horror in unknown unknowns, in denials or aporia that arise from encountering what is hard to accommodate. This is the foundation of a fear of the dark, or what looms over the edge of consciousness, outside of our earth’s atmospheres, in deep epistemological space. The solid, inanimate forms are at once liquid and bodily, interior and exterior. Physical and metaphysical, psychological and evidential. Sense is eroded by waves of the unrelenting sea of our own attention. It is our own nightmare, this new information that rips holes in our sails and forces us to use energy generated by our flesh prisons to understand our environment.

To pay attention is to pay attention a lot. The space indicated is not clearly landscape or cosmological space – it is possibly airless, but also a study in disruption in paint; in the relationship between attention and matter. Is distance meaningless? All matter forms and returns to the greater system, to this so-called doom, which is macro-real and therefore calls to be embraced, celebrated. Women nature authors and black-metal apostles unite in their joyful proximity to the cataclysm:

Doesn’t anyone in the world anymore want to get up

in the

Middle of the night and

sing?10

There are frozen flows that are openings. The light flare is that of early photography, the magnesium blast Painting indexes this new way of seeing. The frame demarks an entrance into which things can flow, in and out. This is the intimate generosity of a painting.

A camera pans past a building in a street with many vacant lots – demolitions have taken place, but not recently. It is implied that the viewer is moving past in a vehicle, looking for accommodation. The building is two-storeyed, made of stone, and its former entrance is on the left-front corner. The opening has been concreted in so the rectilinear mass neatly follows the lines of the building.

Flows shift sediments, rocks. Planes tilt. Surfaces move. Mudflows, fresh slips, wash-outs. Unseen forces. Glaciers grind out valleys and retreat. Glacially.

High in the mountain passes there is a sound in the background like the constant shifting of a sea caused by the wind rushing across the tops of the ranges. I imagine this excites the air’s molecules and makes the effect of ozone, and it renders those able to hear it more psychically open, to elements and whatever other forces are in play. It is rare that being dominated and altered as if porous feels calmly acceptable.

As we move through time it becomes easier to write from the subject position of a ghost, becoming less and less sensible to others. This is a kind of bliss, as much as a loss of attention and care. It is the way of the world. Attention itself is a kind of apocalypse.

Sometimes the desire to be lost again, as long ago, comes over me like a vapor. With growth into adulthood, responsibilities claimed me, so many heavy coats. I didn’t choose them, I don’t fault them, but it took time to reject them. Now in the spring I kneel, I put my face in the packets of violets, the dampness, the freshness, the sense of ever-ness. Something is wrong. I know it, if I don’t keep my attention on eternity. May I be the tiniest nail in the house of the universe, tiny but useful. May I stay forever in the stream.11