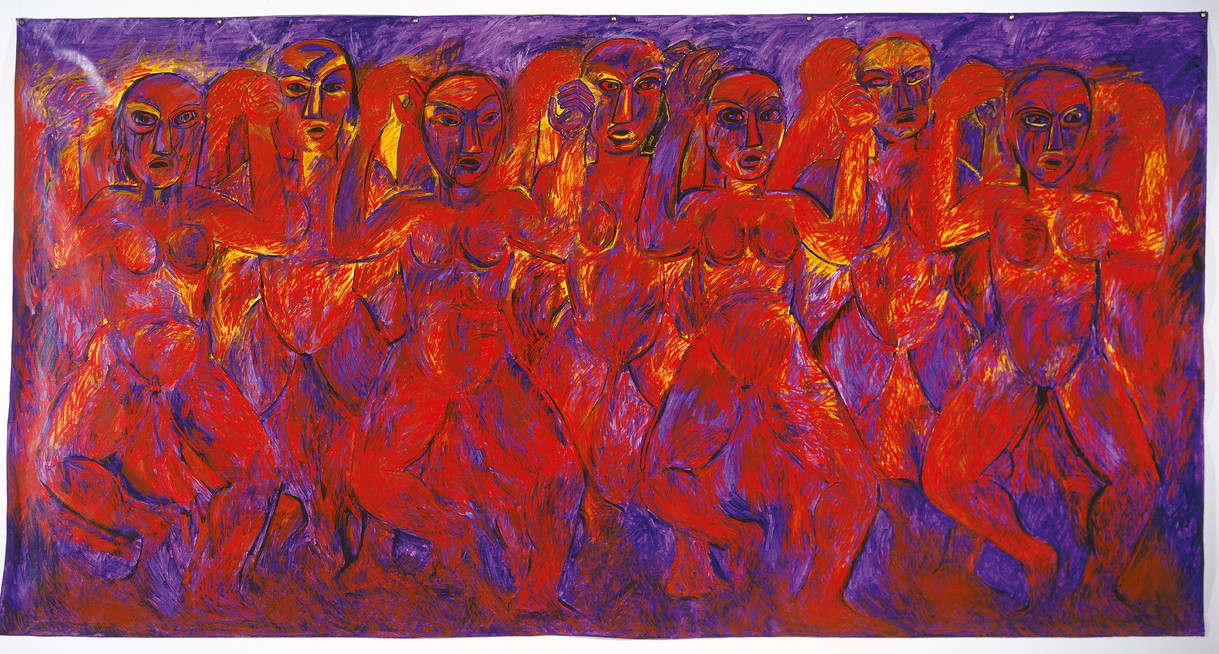

The World Tossed Continuously in a Riot of Colour, Form, Sound

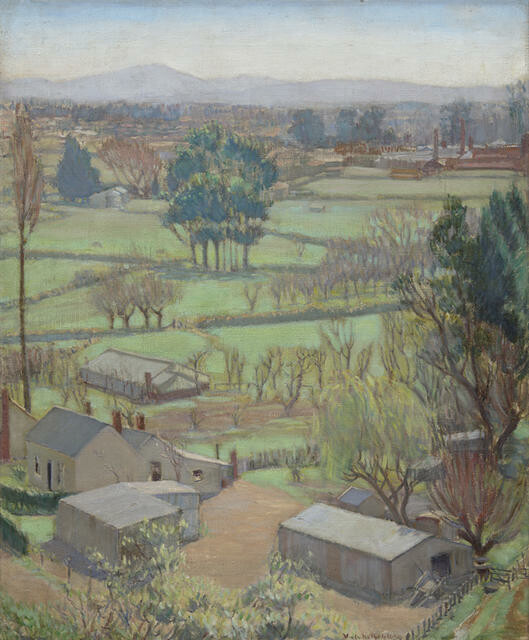

Evelyn Page Morten Hampstead, Devon 1937

Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1986

One hundred and twenty five years ago, after years of political struggle, Aotearoa New Zealand granted all adults the right to vote by extending suffrage to women. To mark this anniversary, for this issue of Bulletin our curators have written about some of the Gallery’s significant – yet lesser-known – nineteenth and mid-twentieth-century works by women. Our intention is to make these paintings, and the cultural contribution of the artists, more visible in 2018.

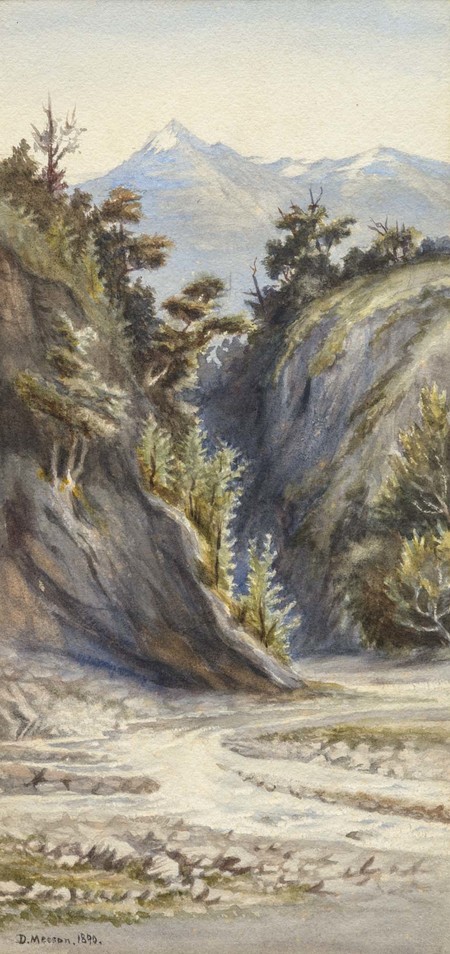

Dora Meeson At the Head of Lake Wakatipu 1890. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2016

DORA MEESON

The suffrage petition of July 1893 – Kate Sheppard’s “monster roll” – contained almost 32,000 signatures from throughout New Zealand. That September, the right of all New Zealand women to vote was secured in law, and they exercised it enthusiastically in large numbers at the next general election. One name, six lines down on the petition’s third sheet, was confidently penned with a certain artistic flair. It belonged to Dora Meeson, a young art student at Canterbury College who became not only an accomplished and respected painter, but a pioneering figure in the Australian and British suffrage movements. Later known as Dora Meeson Coates, she was described as “an ardent feminist, all her life”.

Meeson had been born in Melbourne in 1869. Her father John, a Lancashire-born schoolmaster, took his family with him when he left Australia and returned to London to study law in 1876. Following his admission to the bar, the family migrated to New Zealand, where he practised law throughout the South Island, and they later moved to Christchurch. Dora attended the Canterbury College School of Art from 1889 until 1895 and exhibited with the Canterbury Society of Arts from 1889 to 1907 (sending work back to Christchurch from England in later years). She was an active member of the Palette Club, a progressive group of young artists dedicated to creating original works painted directly from nature. This watercolour from 1890 is likely to have been painted on one of the group’s many field trips, and looks back towards the mountains from Lake Wakatipu, taking in a stream and tree-lined gorge. Deftly observed, it provides an early indication of the radiant colour that would become a hallmark of Meeson’s practice.

After returning to Australia to study at Melbourne’s National Gallery School, Meeson attended the Slade School of Art in London and then the Académie Julian in Paris, where she was considered one of the most promising students. In 1898, her Portrait of M’selle M… was hung at the Old Salon. While in Paris, she became secretly engaged to the Australian artist George Coates, with whom she had studied in Melbourne. They married in London in 1903, forgoing the financial support of Meeson’s wealthy family, who were less than enthusiastic about her partner’s prospects. Renting Augustus John’s flat in bohemian Chelsea, they eked out a modest living, drawing small black and white illustrations for the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Dr Henry Smith’s Historian’s History of the World, which Meeson considered valuable training for her later work as a political cartoonist. As an antidote to their cramped living arrangements, she began a series of marine paintings, working plein-air from a small boat on the Thames. At the time, this genre (and especially her mid-water vantage point) was considered the sole preserve of male artists, but her Thames paintings, which included gritty scenes of labourers on the waterfront and hulking powerplants, were well received. One was purchased by H.R.H. Princess Louise, Queen Victoria’s daughter, and Meeson became the household’s main breadwinner.

In 1907, Meeson joined the Artist’s Suffrage League, designing posters, booklets, postcards and banners for the sophisticated visual campaign to win public support for British women’s suffrage. A talented cartoonist, she was one of the earliest women to work in press illustration in Britain. In June 1911, the Sunday before George V became King, the Women’s Suffrage Coronation Procession was held in London, taking canny advantage of public viewing stands already in place. 40,000 people marched, the women wearing long white dresses, and the seven-mile-long procession took over three hours to pass any point. Meeson and Coates marched at the head of the Australian and New Zealand contingent, carrying a large banner painted by Meeson. Under the words “Trust The Women Mother As I Have Done”, it depicted Australia as a young woman carrying a shield adorned with the Southern Cross, urging Britannia to follow the examples set by New Zealand and Australia. Both had already granted female suffrage, in 1893 and 1902 respectively (though it should be noted that suffrage was not available to all indigenous Australian women until 1962). Meeson’s banner remained in London until 1988, when the National Women’s Consultative Council of Canberra purchased it as a bicentennial gift for the women of Australia. Now held at Parliament House in Canberra, it inspired the design of the Australian “Women’s Suffrage dollar” coin in 2003.

During World War I, Meeson provided aid for Belgian refugees and helped to found the English Women’s Police Service, designed to protect women and children against legal and police discrimination. She later recorded the RAF cookhouse she had visited between duties in a painting now held by the Imperial War Museum. Meeson’s commitment to social justice was lifelong – Australian friends claimed they “never knew when they would next hear of her hunger-striking in gaol.” Her oeuvre included many “conscience paintings”, highlighting the vulnerability of the poor, particularly women, to official discrimination. When George Coates died suddenly in 1930, Meeson turned her energies to ensuring his work was appreciated and preserved in Australian collections. She wrote a biography on his life and work, which also provides insights into her own career. She continued to paint actively until her death in 1955, including a series that recorded the devastation wrought on London’s people and buildings during the Blitz.

Felicity Milburn

Curator

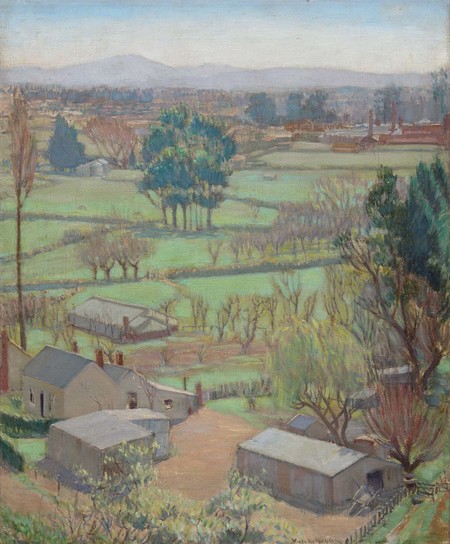

Viola Macmillan Brown Notariello Across the Plains 1931. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Antonietta Baldacchino and Felicity Brichieri-Colombi 2007

VIOLA MACMILLAN BROWN NOTARIELLO

The 1931 Christchurch Group show opened on 10 September, and included one of Viola Macmillan Brown’s most recently completed works, Across the Plains. The thirty-three year-old artist chose an elevated vantage from which to fix this early spring view in her own neighbourhood, taken from a morning walk across the Cashmere Hills’ lower-eastern slopes. Beyond the corrugated iron sheds, worker cottages and greenhouse of the foreground she captured open space, broken by clustered trees, hedges and Ōpāwaho Heathcote River. At the edge of the canvas, in the distant right, she framed the Centaurus Road brickworks, and in the far distance Maukatere Mount Grey, visible through the lifting haze.

Some of Viola’s exhibited works were painted in England in the previous year. Between March and early December 1930 she had toured Britain and Europe with her then 85-year-old father, prominent Pacific scholar and chancellor of the University of New Zealand, Professor John Macmillan Brown. A widower then for almost three decades, the Scottish-born professor depended much on Viola for company. He had arrived in 1874 to be a founding professor at Canterbury College and, in 1886, married one of his earliest students, Helen Connon. In 1881 Connon had become the first woman in New Zealand to gain a Master of Arts, and the first in the British Empire to attain this with honours; she was also principal of Christchurch Girls’ High School for twelve years from 1882. Tragically, she died in 1903, when Viola was just six and her sister Millicent fifteen.

The professor upheld great ambitions for his daughters. Millicent completed a BA in languages in Sydney before studying at Cambridge and in Germany, returning shortly before World War I.1 Viola, who reminded him of Helen, was intended for honours and prizes at Oxford. Feeling dominated by his expectations, however, she “decided to do something that he knew nothing about”, taking up painting studies at Canterbury College School of Art in 1915 (alongside lifelong friends Evelyn Polson and Ngaio Marsh).2 From 1919 she studied at Julian Ashton’s Sydney Art School, and exhibited in Sydney as one of Eleven Australian Women in June 1921.3

In February 1921, against her father’s wishes, Millicent had married Archibald Baxter, a farmer who had suffered much for his pacifist beliefs during the war.4 (Their children were Terence, born 1922 and the poet James K. Baxter, born 1926.) Viola spent two months with the Baxters in Central Otago from January 1922, then – as she later recounted – “because my father didn’t want me also to marry a farmer, or anyone for that matter … he whisked me away to England to the Slade”, a leading art school in London.5 After more study in Paris, she wrote from London to friends in Christchurch of plans to visit Scotland before taking further art studies in Florence.

Viola returned reluctantly to Christchurch in October 1924, via San Francisco and accompanied by her father, who “then wanted [her] as companion, chauffeur, librarian, secretary”.6 Soon afterwards, having learned to speak Italian in Florence, she was introduced to Antonio “Angelo” Notariello, an Italian operatic tenor who had taken up residence in the city as a singing tutor in the previous year. Angelo fell in love at once; when Viola eventually agreed to marriage, her father expressed his disapproval in the strongest terms.7 Although deferring to his decision, they were secretly engaged and remained committed even after Angelo’s return to Europe in 1927.

Viola exhibited with the Canterbury Society of Arts for the first time in 1925. In August 1927 she became a founding member of the circle of modest progressives known as the Group. Following her father’s death in 1935, she oversaw the sale of his house and its contents – and his bequest of 14,000 books to Canterbury College – then left for England. She and Angelo married in Bournemouth in November 1936. Viola Macmillan Brown Notariello continued to paint and exhibit in England, and they had two daughters; happily, their future together was a success.8

Ken Hall

Curator

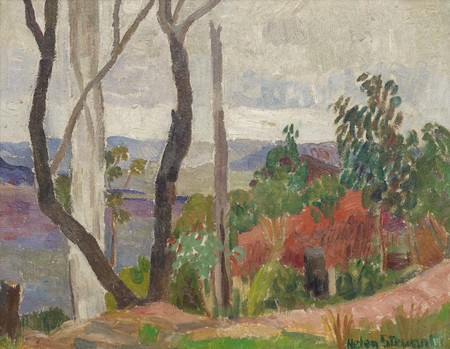

Helen Stewart Bush Landscape c.1935

Oil on canvas board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2017

HELEN STEWART

I really had no idea who the painter Helen Stewart was, what she got up to or indeed what she had painted, until very recently. Part of the reason for my lack of knowledge is that her work is so poorly represented in New Zealand public collections, not least this gallery’s.

So I was stoked to be able to add Stewart’s Bush Landscape to the Gallery’s collection last year when it came up for auction. The work is undated and simply titled, but the scene has the unmistakable feel of an Australian landscape. Bush Landscape most likely dates from the mid 1930s, a period when Stewart was living and working in Sydney alongside leading Australian modernist painters including Thea Proctor and Grace Cossington Smith.

While Stewart’s formative art studies were under Harry Linley Richardson at the Wellington Technical College, it was several trips to Europe during the 1920s and 1930s that really informed her painting practice in modernist principles. There she studied at the London Art School, the Paris Académie Colarossi and, also in Paris and perhaps most importantly, with the cubist painter André Lhote in 1932. Under Lhote she received a basic grounding in cubism with an emphasis on form, structure and colour in painting.

Stewart’s time living and working in Sydney from 1933 was a highpoint in her career. In Sydney she became part of the city’s lively modernist scene. She formed a close friendship with Cossington Smith, who is today considered to have been one of the leading exponents of modernism in Australian art at the time. Stewart had access to a car and the pair would frequently head out on painting trips around Sydney and further afield to Bowral, Moss Vale and Berrima in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, searching for landscape motifs.9

Stewart exhibited regularly in Sydney with the Contemporary Group and Macquarie Galleries, the city’s leading dealer gallery at the time. Her portraits and landscapes were regularly praised in the press, although one reviewer did warn visitors “who insist on literal truth to nature in oil paintings … to stay away from Miss Helen Stewart’s exhibition: for those pictures at the Macquarie Galleries will either puzzle them or stir in them anger. Other people, who are prepared to sacrifice the photographic element in favour of a keen imagination, which brings deeper elements of nature to light through formalised pattern arrangements, will be likely to find the exhibition very interesting indeed.”10

In 1937 Stewart featured in an article on New Zealand women painters working in Sydney alongside other painters including Adele Younghusband and Maud Sherwood. The writer acknowledged the number of New Zealand women artists currently working in Sydney who were “doing a great deal of interesting work”.11

The end of World War II saw Stewart return to New Zealand where she settled in Wellington in 1946. Her painting moved ever more towards abstraction, something that Cossington Smith frowned upon. In Wellington she exhibited at Helen Hitchings Gallery and the Architectural Centre but her profile faltered somewhat. Her work has only been collected by a handful of public galleries in New Zealand and Australia and she was not included in Gordon Brown and Hamish Keith’s An Introduction to New Zealand Painting 1839–1980 or Michael Dunn’s New Zealand Painting: A Concise History. Anne Kirker however did include an in-depth look at Stewart’s painting in New Zealand Women Artists: A Survey of 150 Years, a book that I now feel the need to reread.

For me, Bush Landscape makes a very welcome addition to the Gallery’s collection. It’s a great painting, and the way the landscape is simplified into forms and shapes according to the artist’s vision appeals to me. Not only is Bush Landscape the first work by Stewart to be acquired by the Gallery, but it also helps in some way to shine a light on the work of a New Zealand painter whose paintings were respected and admired by the leading contemporary Australian artists of the day with whom she rubbed shoulders.

Peter Vangioni

Curator

Edith Munnings Fisherman’s Hut, Redcliffs c.1889. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by G.E. Munnings and C. Munnings, Christchurch 1970

EDITH MUNNINGS

Joseph and Emma Munnings emigrated from England to Ōtautahi Christchurch in 1859, settling in Addington and raising eleven children. The Munnings family had artistic leanings – one son, Joseph, studied architecture in England and became architect to the government of Eastern Bengal and Assam, later also building in New Zealand and Australia; a cousin, the English painter Alfred Munnings, went on to become president of the Royal Academy, London.

Edith Munnings studied at the Canterbury College School of Art between 1889 and 1893; Margaret Stoddart and Dora Meeson were fellow students. In her first year she won a prize from the Auckland Society of the Arts for a still-life painting in oils and she would continue to exhibit regularly with both the Canterbury and Auckland arts societies. Munnings became a student assistant at the Canterbury College School of Art in 1892 and member of staff in 1894; among her students was Elizabeth Kelly.

In 1897 at age thirty, Edith joined her brother Joseph and around fifty New Zealanders working at a mission in Pune, India. She would return to Christchurch on leave and sell her paintings to fundraise for the mission. In 1900 she married an Australian, the Rev. Henry Strutton, and they remained in India dedicating their lives to mission work. She continued to paint as Edith Strutton, working mainly on a small scale and in watercolours – her skill apparent as the heat would quickly dry the paint on the page. Edith Emma Munnings Strutton died in Lonavala, India, in 1939.

In her painting Munnings focused predominantly upon her immediate environment. This humble cottage was set upon the shoreline of Ihutai at Te Rae Kura or the estuary at Redcliffs, which was known for a while as Fisherman’s Flat. The first wave of Pākehā to settle the area were fishermen, who built rough huts and cottages along the foreshore. Munnings’s painting is at first picturesque. However, with hindsight the scene starts to feel like a ‘last look’ as the next wave of settlers were in hot pursuit, purchasing the serene and perfect land for yachting and pleasure boating.

Rapanui (Shag Rock) can be seen off in the distance. Rapanui means ‘the great sternpost’, and for Māori it acted as a guide into Te Ihutai estuary and the mouths of the adjoining Ōtākaro Avon and Ōpāwaho Heathcote rivers. Before European settlement, Ōtautahi was characterised by a network of rivers, which made for efficient supply of mahika kai (food and other resources) around its various kāika (villages). The Ihutai estuary area was an excellent location for fishing tuna (eel), kanakana (lamprey), inaka (whitebait), and pātiki (flounder).

Te Rae Kura can be translated as ‘the glowing red headlands’ and was home to Waitaha, then Kāti Mamoe and finally Kāi Tahu around the seventeenth century. By the mid nineteenth century, Alfred Watson owned 150 acres of the area; the Watsonville sections were later subdivided and a section was named Clifton. In 1898 when a local Post Office was applied for the Government noted there was a Clifton already in the Dominion, and the name Redcliffs was given. These days a revival of Māori place names is underway and place names like Te Rae Kura Redcliffs are becoming part of the post-earthquake vernacular.

Nathan Pohio

Assistant curator

Evelyn Page Morten Hampstead, Devon 1937. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1986

EVELYN PAGE

It’s an uncomfortable truth that some works in the collection receive more love than others – if love can be measured by the amount of time a work spends on display in the galleries, as opposed to the twilight fastness of the collection storerooms. I’m confident that the Gallery curators would find something to love in almost every work that we care for. But some works – by consequence of their sheer physical scale, or the urgency of their subject, or their place in an artist’s oeuvre – simply command more attention than others.

Evelyn Page’s Morten Hampstead, Devon is a work that’s spent a lot of time on the painting racks, waiting to be looked at. It’s been on display only a couple of times since it came into the collection in 1986, and that’s not because it’s a slight painting (it’s gutsy and terrific!) or an uncharacteristic work by this artist. Instead, I suggest that it hasn’t been out much because it’s difficult to place. Or rather that its place is difficult.

The story of New Zealand art in the 1930s and 1940s is usually told as a quest for national identity. Artists and critics anticipated an art that would belong to New Zealand and express something fundamental about what it was like to live here, rather than placing a British or European frame on the land in the way of earlier generations. Evelyn Page is part of the national story, one of a loosely associated group of painters working in Canterbury between the wars. Her brushwork was a little looser than her contemporaries Rita Angus, Viola Macmillan Brown and Louise Henderson, her colour palette more intense and direct (her interest in painting the female nude in the landscape belonged to her alone). But her views of the dramatic landforms of Governors Bay, where she made her home in the late 1930s, are part of this country’s modern landscape tradition. The painting she made twelve thousand miles away in Moretonhampstead on the outskirts of Dartmoor in Devon, however, is not.

Evelyn Polson had joined her friend (and later husband) Frederick Page in England in 1937. He was studying at the Royal College of Music and convalescing after a serious illness. They stayed for a time in Exeter, the county town of Devon, where Page completed her Moretonhampstead painting and another work, Outskirts of Exeter. She brought both back with her to New Zealand.

As chance would have it I was born in Exeter, and lived as a small child in a village not far from Moretonhampstead. The first painting I can remember seeing – and loving – in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter, a place we regularly visited as a family, was Robert Bevan’s A Devonshire Valley (1911). My mother bought me a postcard of it; I stuck up the image on the wall of my bedroom as a child, and have never quite been able to get it out of my head. When I came across Page’s painting recently I was struck by the resemblance. Some of that, of course, is down to the subject matter; the compact stone buildings, the patchwork fields, the deep red earth of Devon, the umber patches of dried bracken, the violet shadows, the moors rising grey-purple in the far distance – but there’s a similarity of treatment in both Bevan’s and Page’s view of the landscape, an embrace of direct colour applied in bold patches to capture the intensity of the water-soaked local light, which connects the two works.

Page didn’t see Bevan’s painting in Exeter, but she may well have been familiar with his work from her time in London on the same trip. Bevan was a member of the Camden Town artists group, a post-Impressionist who was possibly the first British painter to have used pure colour in his works. He exhibited with Augustus John, whose work Page admired – and borrowed from – in her well-known portrait of the poet and collector Charles Brasch, which she painted in a friend’s Bayswater flat on the same trip. Looking back on the time he sat for Page, bribed to keep still with her homemade chocolate fudge, Brasch described Page as a painter “for whom thought came only in feeling, whom the world tossed continuously in a riot of colour, form, sound.”

The trouble with a painting like Page’s Morten Hampstead, Devon is that it doesn’t have a ready context; it’s as much if not more part of the history of British painting as it is of New Zealand’s, though Page was not a British painter. It caught my eye because I know not only the landscape it depicts but the art historical context which it can be related to. Its status as an outlier in Christchurch’s art collection, however, might reveal something of the complexity and nuance of a period of art history in which New Zealand artists were usually seen as inward-facing. Perhaps it’s not so much that the work doesn’t fit, but that the narrative needs to expand.

Lara Strongman

Senior curator