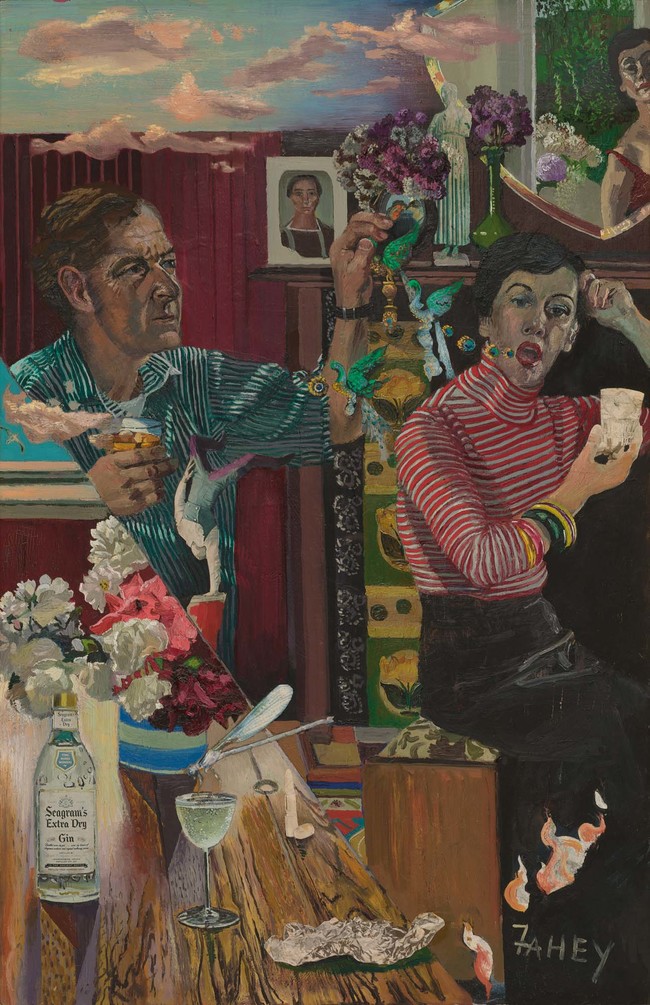

Jacqueline Fahey My Skirt’s in Your Fucking Room! 1979. Oil on board. Collection of William Dart, Auckland

An Undeniable Promise

There is such a burden of expectation placed on Anne’s painting, and on the exhibition… itself. I feel, like many women painters that she is being asked to prove an undeniable promise. This is unfair.1

My only interaction to date with the eminent Jacqueline Fahey was earlier this year, when I got the chance to be her editor for an article about Anne McCahon. It was an intimidating task, not only because it was Fahey, but also because it was one artworld pioneer writing about another – matriarchs to be specific. The end result was a revelation, full of insights into Fahey’s and McCahon’s relationship, and into the conversations of the time; the difficulties they faced as artists and their expected role as women in general. Jacqueline Fahey: Say Something! at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū is a much deserved and needed survey of Fahey’s influential domestic interiors from the 1970s and beyond. Say Something! bears this same burden of feminism and is, perhaps, another exhibition asked to prove an undeniable promise.

In her assertion of lived female, and feminist, experience as a valid subject for artmaking, Fahey was one of the first New Zealand artists to paint from a woman’s perspective. Fahey started painting in the late 1950s, before taking time out for her three children and her husband’s demanding career. But by the late 1960s she had taken to painting again, and she has rarely stopped since. In a 2012 interview for the Listener with Sally Blundell, Fahey commented, ‘Saying that this [the home] is an important arena was a defensive act for women. Reality is not ‘somewhere else’. Big decisions aren’t just made when you go off to the office or the boardroom. They are often made in the kitchen.’2

Jacqueline Fahey Augusta and Voss 1962. Oil on board. Collection of the artist

Fahey’s vigour and politics were very reflective of the time. In the 1960s, the world of the New Zealand woman was limited in almost every respect, from family life to the workplace. A woman was expected to follow one path: marry, start a family quickly and devote her life to homemaking. As one woman quoted in A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s put it, ‘The female doesn’t really expect a lot from life. She’s here as someone’s keeper – her husband’s or her children’s.’3 The feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s began in reaction to this gender inequality and was known as the second wave of feminism (the first wave being the suffrage movement).

Originally focused on dismantling workplace inequality, such as denial of access to better jobs and salary inequity, via anti-discrimination laws, the motivations expanded to other concerns such as abortion. In the United States, public ‘Speak-outs’ were held, where women admitted to illegal abortions and explained their reasons for doing so, removing the shameful stigma. This idea of needing to speak out mirrors that of Fahey’s need to ‘say something’, which typifies both the feminist movement and the feminist art movement that emerged at the same time. At a moment when the idea that women were fundamentally inferior to men was being criticised, feminist art was critical of gender expectations within the industry and the very male art historical canon, making work through a staunchly feminist lens.

This critique of the canon was perhaps best typified in a 1971 essay by Linda Nochlin, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ She wrote, ‘The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education.’4 Women brought to light the patriarchal history in which almost all famous art was made by men and for men.

However, fast forward to 2017, and the world for women is very different – as too is the feminist conversation. There are far fewer discriminatory laws against women, and women no longer need to marry for economic security. Yet as American writer Jessa Crispin comments, ‘just because a certain population of women – who are mostly white, educated and upper middle class – can participate in higher levels of society, that doesn’t make it a victory for all women … it’s the collective that needs taking care of.’5 And so, the feminist movement is currently in perhaps its biggest expansion yet through the mobilisation of women of colour, indigenous women and trans women, who are ensuring that feminism includes every type of woman.

Much of this expansion of the feminist movement is indebted to the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw, who introduced intersectionality to feminist theory in the 1980s. Crenshaw’s focus is on how the law responds to issues that include gender and race discrimination. The particular challenge is that antidiscrimination laws look at gender and race separately; consequently African American women and other women of colour experience overlapping forms of discrimination and the law, unaware how to combine the two, leaves these women with no justice.

Jacqueline Fahey Drinking Couple: Fraser Analysing My Words 1978. Oil on board. The University of Auckland Art Collection

Crenshaw often refers to the case DeGraffenreid v. General Motors in writing, interviews and lectures. In this 1976 case, a group of African American women argued they were receiving compound discrimination excluding them from employment opportunity. They contended that although women were eligible for office and secretarial jobs, in practice such positions were only offered to white women, barring African American women from seeking employment in the company. The courts weighed the allegations of race and gender discrimination separately, finding that the employment of African American male factory workers disproved racial discrimination, and the employment of white female office workers disproved gender discrimination. The court declined to consider compound discrimination, and dismissed the case.

The term gained prominence in the 1990s when sociologist Patricia Hill Collins reintroduced the idea as part of her discussion on black feminism. This term replaced her previously coined expression ‘black feminist thought’,6 ‘and increased the general applicability of her theory from African American women to all women’.7 Much like Crenshaw, Collins argued that cultural patterns of oppression are not only interrelated, but are bound together and influenced by the intersectional systems of society – such as race, gender, class and ethnicity – referred to as ‘interlocking oppression’.

Feminists and feminist artists today argue that an understanding of intersectionality is a vital element to gaining political and social equality and improving our democratic system. Collins’s theory represents the sociological crossroads between modern and postmodern feminist thought. This diversification of feminism is known as the third wave, and the fourth wave seems to have moved all of this online.

With such a varied understanding of what feminism is, the question of feminist art practice within Aotearoa is bit of a head scratcher. While women at the vanguard of the second wave such as Fahey, and matriarchs such as Judy Darragh twenty years later, are easy to point out as feminist artists, it seems almost impossible to pinpoint with emergent practices today. I am not even sure how you would frame a feminist lens in 2017, conceptually let alone aesthetically. Yet while considering all of these advancements to feminist thought, it is astounding that one thing has not changed: the pay gap is still huge, especially within the arts. This highlights the simple fact that despite it all, the system itself is still incredibly patriarchal. So then the question becomes, is feminism whatever acts in opposition to the patriarchy?

Jacqueline Fahey In Memoriam 1969. Oil on board. Private collection, Wellington

One collective which acts in direct response to this undervaluing of women by diversifying the art community is Fresh and Fruity. Co-directed by Mya Middleton (Ngāi Tahu) and Hana Pera Aoake (Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Te Wehi, Ngāti Raukawa), Fresh and Fruity was founded in 2013. The all-female collective started as a physical space in Ōtepoti Dunedin, and now functions completely online. Their work is pushing boundaries in terms of opening up safe spaces, having women control their own representations, and challenging expectations around the way women’s art is presented.

Another collective of emboldened women making great art is Mata Aho, which comprises Erena Baker (Te Atiawa ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Toa Rangātira), Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe), Bridget Reweti (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi) and Terri Te Tau (Rangitāne ki Wairarapa). They produce large-scale textile works with a single collective authorship within the contemporary realities of mātauranga Māori. And earlier this year they were among the first ever New Zealand representatives to Documenta alongside Nathan Pohio and Ralph Hotere, something which is made all the more satisfying because they are all mana whenua women.

FAFSWAG is another collective which undeniably represents this new wave of feminism. The platform provides a space as well as visibility for members of the Pacific rainbow community. A big part of that has been exposure for Pacific trans women in performance art across Aotearoa in spaces such as Artspace, ST PAUL St Gallery and CoCA, as well breaking into more traditional performance arts spaces such as the Basement Theatre.

In 1980 feminist Lucy R. Lippard, commented that feminist art was ‘neither a style nor a movement but instead a value system, a revolutionary strategy, a way of life.’8 I can’t help but think that statement is truer now than ever. To try to pinpoint feminism today seems counterproductive to the widening of conversations about mobility, equity and visibility that is diverse and local. Rather than locating artists to, in Fahey’s words, provide the undeniable promise, perhaps it is as simple as just being a woman working within a patriarchal art system. Would that make all women working within this industry today feminists?