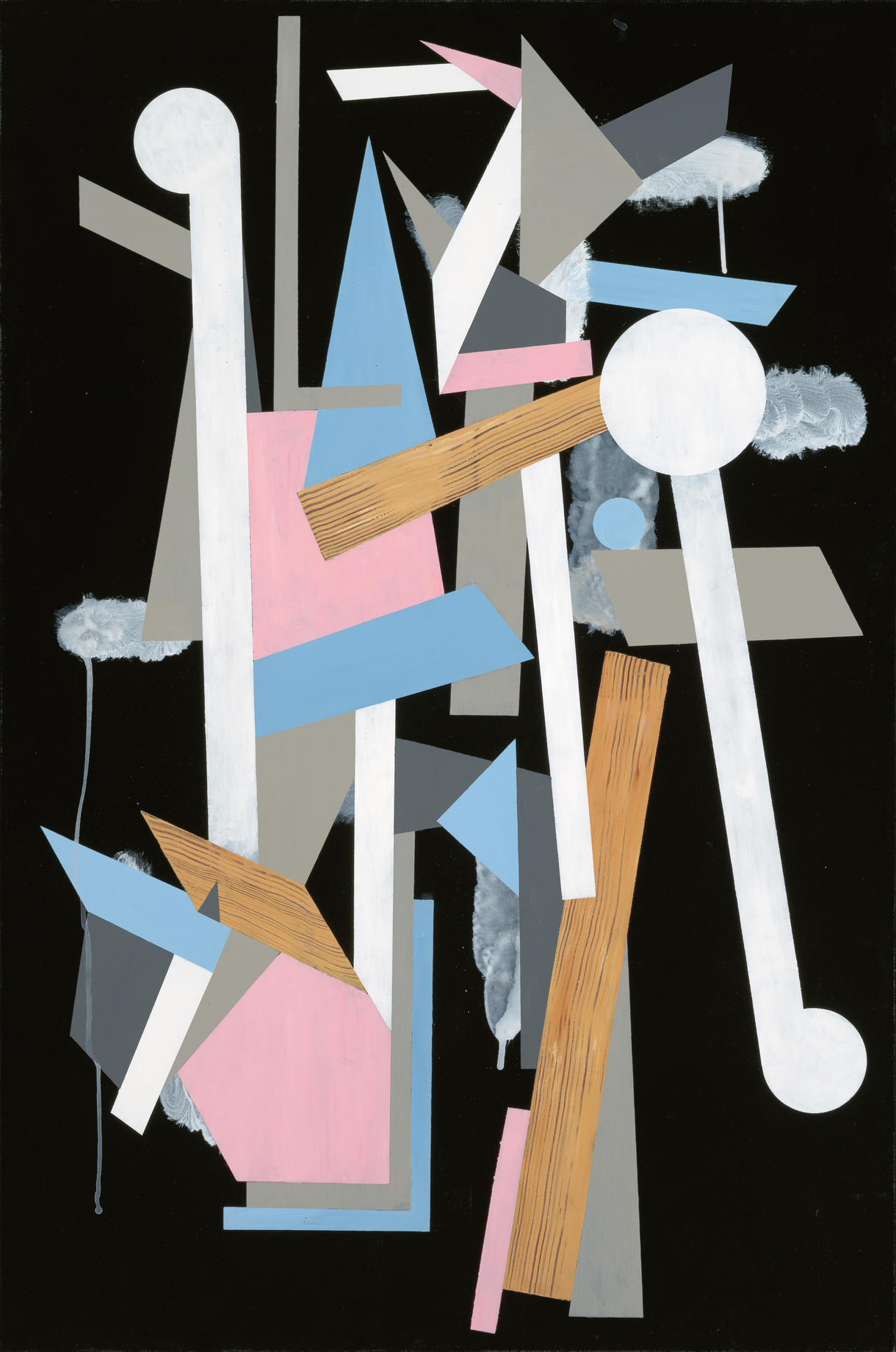

Tony de Lautour Silent Patterns 2015–16. Acrylic on board. Commissioned by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Photo: John Collie

Silent Patterns

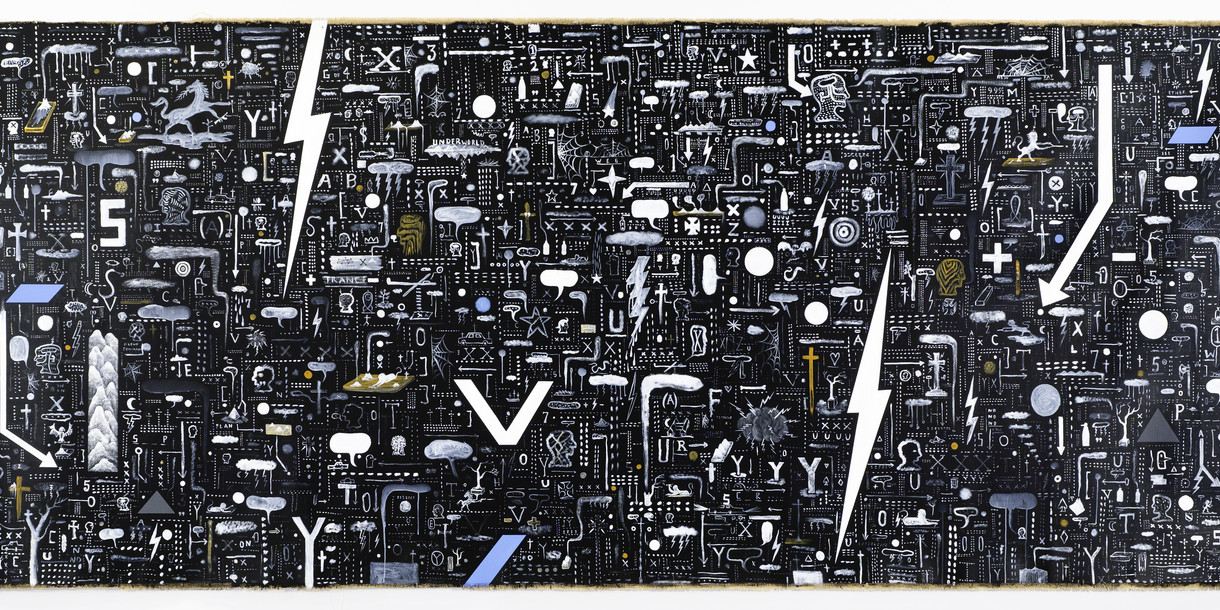

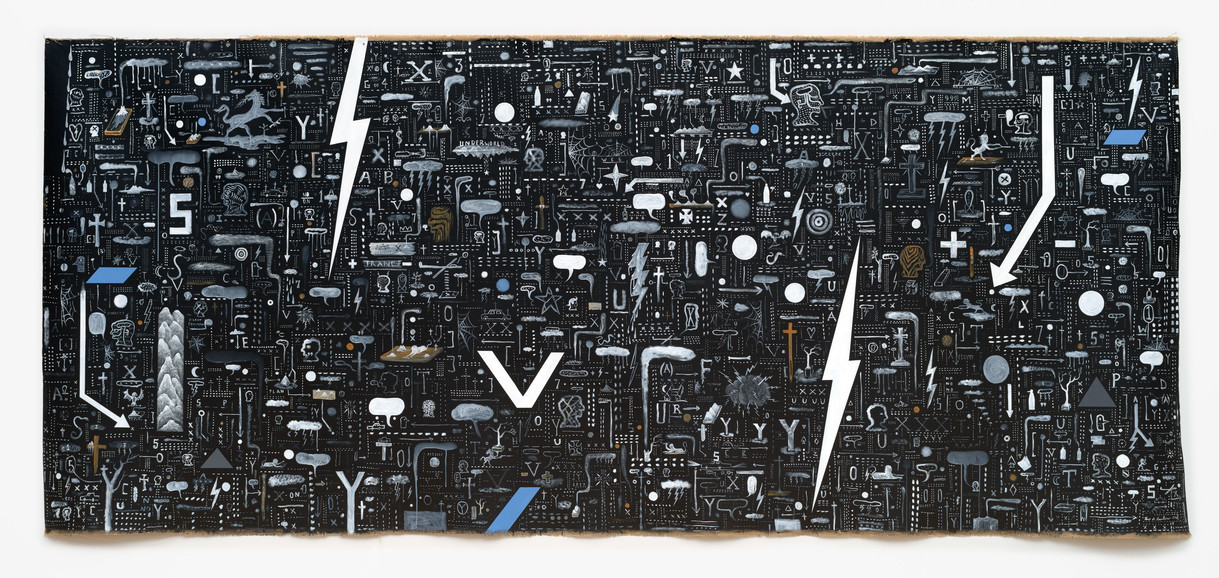

When we asked Tony de Lautour to produce a new work for the Bunker—the name Gallery staff give to the small, square elevator building at the front of the forecourt on Montreal Street—he proposed a paint scheme inspired by Dazzle camouflage. Associated with the geometric near-abstraction of the vorticist movement, Dazzle was developed by British and American artists during the First World War to disguise shipping. It was a monumental form of camouflage that aimed not to hide the ship but to break up its mass visually and confuse enemies about its speed and direction. In a time before radar and sonar were developed, Dazzle was designed to disorientate German U-boat commanders looking through their periscopes, and protect the merchant fleets.

Senior curator Lara Strongman spoke with Tony de Lautour in late January 2016.

Tony de Lautour Silent Patterns 2015–16. Acrylic on board. Commissioned by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Photo: John Collie

Lara Strongman: We call the building the Bunker. Did you conceive the project in relation to the name?

Tony de Lautour: As soon as I knew it was a project for the Bunker, I started thinking about something camo or military. I’ve made works with camouflage in them before, and I’ve looked at Dazzle at different times, mainly through Edward Wadsworth’s vorticist prints. With this project, the idea is to disguise or break up the surface shape of the building. With Dazzle camouflage, the object’s still there, but you’re confused about where it is in relation to you, and in relation to horizon lines. The point wasn’t to hide the object, but to break it up into facets. Imagine looking through a submarine periscope—you’re not quite sure what it is that you’re seeing, what you need to zero in on, to target.

LS: What you’ve effectively done is make the Bunker building look like the conning tower of a massive underground submarine, or the bridge of a battleship.

TdL: Something that’s just resurfaced, but is locked in the land.

LS: How does this idea relate to other recent works of yours?

TdL: I’m using abstract shapes or forms based on the environment around the Bunker. There are curves that echo the curves in the Gallery walls, and I’ve used some of the surrounding colours of buildings; it’s similar to what I’ve been doing in paintings recently. It’s abstract, but maybe based on architecture or plans or zoning maps. There’s a foot in abstraction, and a foot in a representational base.

LS: There’s always been abstraction in your work, but it was quieter than the figuration: hiding there in plain sight. The abstract elements have made themselves more evident over the past few years. A couple of years ago you described abstraction as an escape. What did you mean by that?

TdL: After the earthquakes I found that figurative work seemed a little... facile. I just wanted to deal with shapes. Shapes seemed more real, more like objects. Also, it was a way of dealing with things obliquely. I didn’t want to illustrate the earthquakes; I was making work in that context. I made the Tower paintings—which funnily enough I started before the earthquakes, but continued afterwards—wobbly tower block things. They reference structures and precariousness.

LS: You look at Dazzle camo, and with its curves and straight lines, there’s a way to see it like a detail from a monumental text, an unreadable fragment of gigantic words...

TdL: Like a close up of some sort of typography. They look like they’re sections of something that’s much larger, and maybe that’s the idea: they’re a little section in a larger environment which makes up the bigger picture. They connect to the elements in the same way that a piece of camouflage in earth colours integrates fully with the land. Something painted with Dazzle integrates with its environment, but the object is still there.

LS: Strikes me that your Property Press works, where you painted abstract shapes over glossy property listings, are a form of camouflage.

TdL: Those works reference property and plans, but also twentieth century modernism and its failed utopian ideas. Especially those Russian modernists.

LS: You placed those historical narratives in the context of post-quake Christchurch, with its political machinations over property and ownership and land.

TdL: I reference those sort of things in the titles of the works. For instance, there's one called Tourist Trap, referring to the post-quake thing of bringing people back in to the city to have a look round. I called other paintings Loss Adjuster and No Way In / No Way Out.

Something painted with Dazzle integrates with its environment, but the object is still there

Maurice L. Freedman Dazzle camouflage, Type 17 Design B. Collection of the Fleet Library at RISD. Reproduced with permission

LS: Your earlier revisionist paintings did something similar, by taking an existing ground with its own content and context, then painting over it, adding and obliterating histories.

TdL: Yeah, rewriting histories. After the earthquakes I started revisiting found paintings or found prints; painting over them with a more abstract Cubist-y effect. Some of those were quite simple; a square of black, blacking out what was underneath. But that was also about thinking about prints that people had had that were now gone, blacked out now with the loss of possessions. I was also using ideas of sections and property, blocks of land.

LS: It's an interesting relationship between the abstract works and your earlier revisionist paintings—both inscribe new histories over the top of old ones.

TdL: The connection is that they're both painted on existing works, but with different outcomes. One of them writes a new history on the painting; the other references the blocking out or taking away of an image—or records the rewriting of history by others.

LS: They're both a kind of revision. Is the Silent Patterns project revisionist, too? Painting something out, in order to see the world differently? But perhaps that's what painting always is.

TdL: I tend to paint things to find out what I'm doing. I have an idea of what I want to do, but I have to paint it to find out what it is, or what it's going to be, whether it's going to work; I work my way through an idea by painting it, which is sometimes good and sometimes bad. I also tend to work it out and then go on to the next thing. Sometimes you feel like you should stay with something a bit longer. But then using those found images and found canvases it becomes a bit cyclic anyway. Ideas from ten years ago come back again.

LS: You've always done that—painted in loops. Revised your own history.

TdL: Yeah. Colours or shapes or ideas come round and back again.

LS: When you make new work that riffs off the old, you change the reading of the past work with the introduction of the new.

TdL: I've always thought the old work had a formal abstract element to it, even though the work was largely figurative. Maybe more people are noticing that, now that I've been doing abstract works.

LS: In an interview you talked about the way that text blocks had infiltrated your work, and said you'd become more interested in the geometric forms of text rather than the meaning of words.

TdL: I did those paintings of words and names, but it wasn't so much the words that were important as the shapes they made. They're still hovering around. They've just become shapes now.

LS: You look at Dazzle camo, and with its curves and straight lines, there's a way to see it like a detail from a monumental text, an unreadable fragment of gigantic words.

TdL: Like a close up of some sort of typography. They look like they're sections of something that's much larger, and maybe that's the idea: they're a little section in a larger environment which makes up the bigger picture. They connect to the elements in the same way that a piece of camouflage in earth colours integrates fully with the land. Something painted with Dazzle integrates with its environment, but the object is still there.

TdL: Yeah, it will be. The second biggest would be the bus at Smash Palace, or the long canvas that the Gallery owns. This is an interesting project though. I’ve drawn it up on a small scale; it’ll be interesting to see how it works larger.

LS: What are the considerations for making a big painting, as opposed to a small one?

TdL: It’s about viewing distances. If it’s a small painting you’re seeing the whole thing at once. With this project, you can’t ever see it in its entirety. There’s three walls but you’re only going to be able to see two at once, or one wall straight on; but you will be able to see it from quite a distance. When you get closer to it your sense of the scale will change. But as we’ve been working on this project, the Bunker itself seems to have been getting smaller and smaller. I had an idea of the pattern being more intricate, but in the end I made it bolder. Whether or not it works is the thing. We’ll know when it’s up.