Self portrait of Rudolf Gopas, newspaper clipping from issue 2281 of the Tiroler Tageszeitung, 4 December 1948, p.5. Folder 3a, Box 2, Rudolf Gopas Archive, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archive, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Reflections on riches

Tim Jones considers the challenges and pleasures of archive collections.

While the Gallery may be closed, our archive collections continue to develop. As I write, three aspects of managing an archive are happening simultaneously. We are adding new material, cataloguing it, and assisting a researcher to use the archive. All the challenges and pleasures of archive management are on the table.

Art historian Julie King is working on the papers of Canterbury artist Olivia Spencer Bower (1905–1982). This collection was deposited in stages, mostly after the artist’s death, with Christchurch Art Gallery’s predecessor the Robert McDougall Art Gallery. The fragmented assembly of the papers and the fact that the papers’ original creator cannot be consulted provide archivist and researcher with numerous challenges. Things that might belong together are separated. Items that seem to bear little relation to one another are adjacent. The documents have been used for previous publications and copies or notes resulting from this earlier work have been incorporated as if they were part of the original collection. Despite these complexities, the archival collection is vital as a source of biographical detail, and a path to understanding the artist's life and work.

King says that her research for her forthcoming book 1 began with the artwork—locating watercolours, acrylics, oil paintings, drawings, illustrations and linocut prints. Spencer Bower was an artist who rarely dated her paintings at any period of her career, and looking through diaries and letters in the Archive, as well as exhibition catalogues and reviews played a key part in King's attempt to date individual works.

Material relating to Spencer Bower is also located in other collections, for example at the Alexander Turnbull Library and the Macmillan Brown Library. Artists collaborate and communicate with each other, exhibit in group shows together and otherwise interconnect. The narrative of a single artist’s work is inevitably bound up in the work, and thus in the archives, of other artists, friends and colleagues.

Fortunately the Spencer Bower collection can be browsed not only by looking at the original letters, diaries, sketches and other items—some of which are extremely fragile—but also by consulting a magnificently detailed inventory created by in 2006 by Emma Meyer, then a student at Victoria University.

This inventory helps navigate the archive and reduces the number of times documents need to be handled. King notes: ‘The inventory comprises an indispensable record of 95 pages of precise description of various items, diaries, and photograph albums. Boxes contain folders that can hold an assortment of material accumulated from different periods of the artist’s life: such as letters, a greeting card designed by a friend, a review, handwritten art notes, and an occasional recipe.’

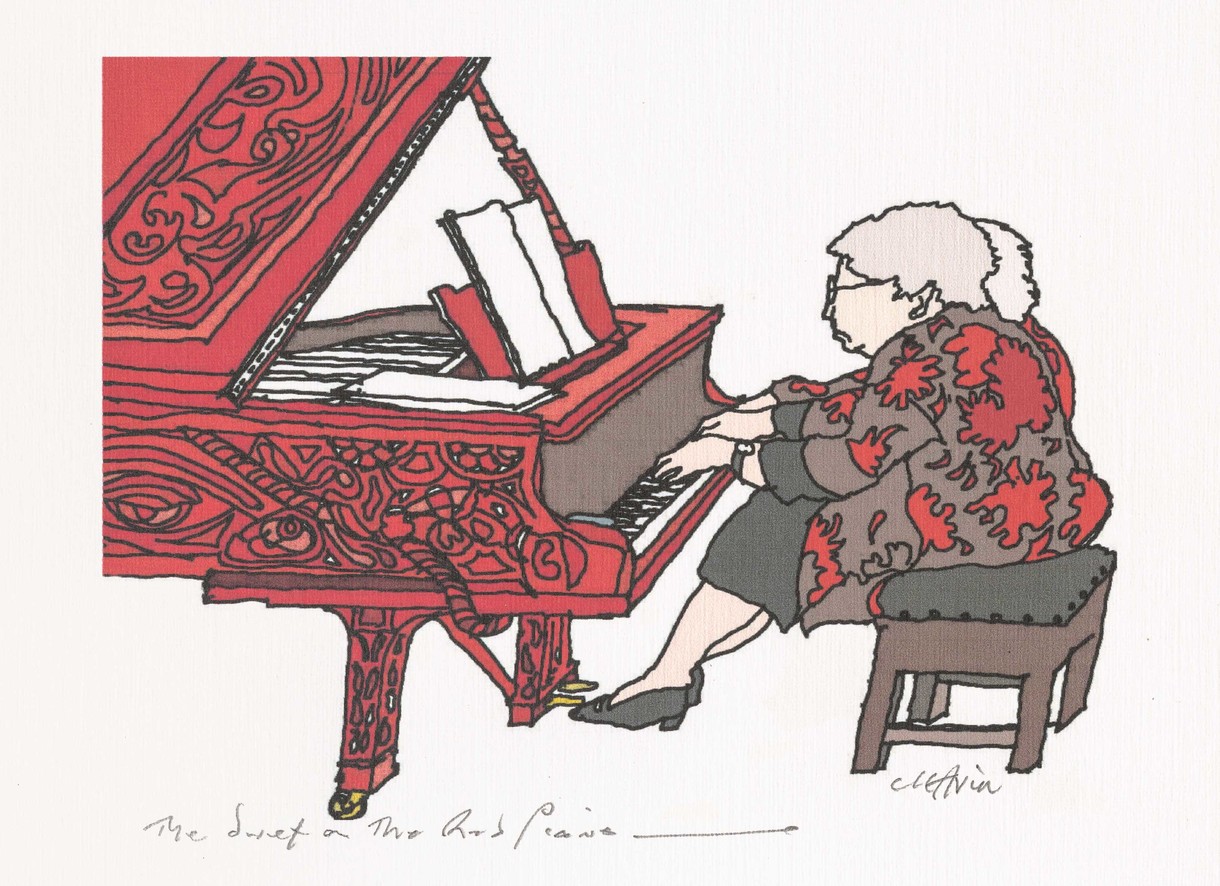

Christmas card from Olivia Spencer Bower. Folder 6c, Olivia Spencer Bower Archive, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archive, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Digitisation can help with both access and preservation of an archive collection, however it is by no means a complete solution. The original document still needs to be retained, and occasionally consulted. Consulting thousands of digital facsimiles is in many ways harder than consulting the same number of original documents and certainly no quicker. Typed or printed text can to some extent be digitally searched using optical character recognition, but handwriting, drawings, and sketches cannot yet be processed in this way. An inventory that can be read by a human and searched by a computer is often a more useful exercise than digitisation.

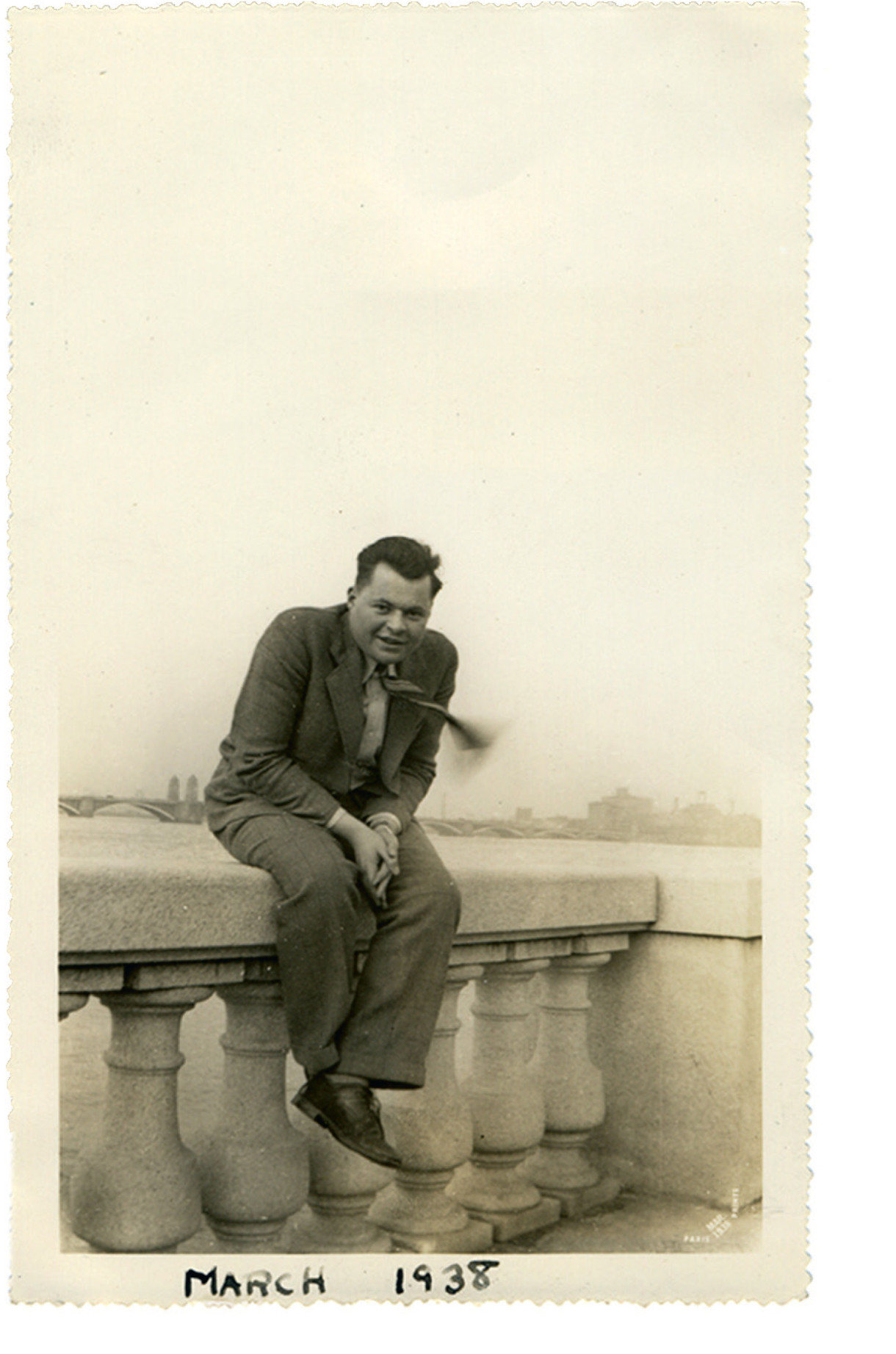

Such an inventory is being created at the moment by Abby Nattrass, an art history student from the University of Canterbury. She is working on the papers of painter and university teacher Rudolf Gopas (1913–1983). These came into the Gallery’s hands through his widow and date largely from the later years of the artist’s life. They were not sorted or arranged by Gopas himself. This inventory will be a list and will also contain selected photographs of documents and drawings whose pictorial quality or whose striking layout cannot otherwise be captured.

Nattrass reflects on her project: ‘Something that struck me whilst working on the Gopas archive was the need to objectively describe each document that came before me. Whilst this sounds like an easy task, it is somewhat difficult to look at items free from presuppositions. For an inventory to be successful I think it must be as objective and factually descriptive as possible, and it is therefore crucial not to place your own value judgments on to items.’

This need to be neutral and objective in writing an archival inventory is crucial. Researchers are entitled to find precision and even-handedness. Judgements and evaluations will come later when archives are used by those researchers to argue particular points. Nattrass points out: ‘This meant I needed to treat loose bits of refill with illegible notes with the same care and detail as a beautiful sketch signed and dated by the artist. This was a challenge and something I constantly needed to remind myself of, especially as more often than not these judgments are done without thinking.’

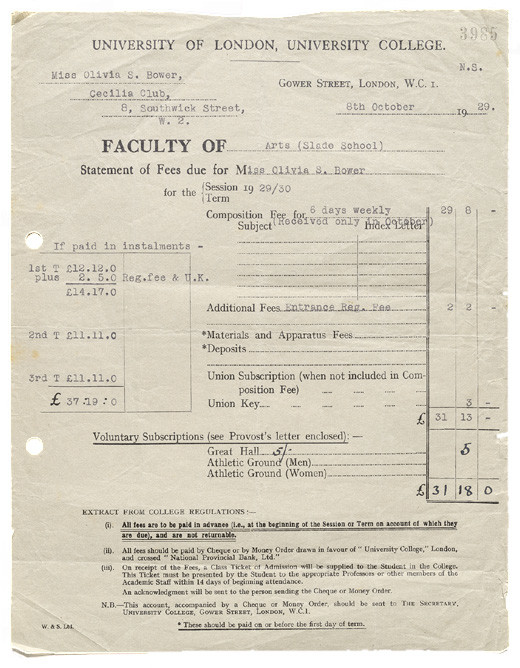

Statement of fees due, University of London, Faculty of Arts, Slade School, 8 October 1929. Folder 6c, Olivia Spencer Bower Archive, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archive, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

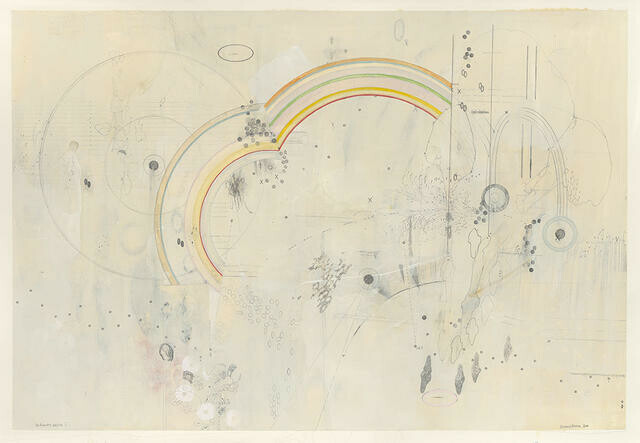

These two archive collections are, each in their own way, highly problematic. They are incomplete and they have been filtered and re-organized without regard for how they originally existed. But we keep them and value them because they both contain treasures of the highest order. Spencer Bower’s diaries and photographs of her visit to Europe in the late 1920s, for example, are peerless documents. Gopas’s intense interest in astronomy and its effect on the human condition cannot be better expressed than in his own heavily annotated handwritten reflections. We accept the challenges that describing and managing an archive collection presents because of the riches they contain. All our archives, in one way or another, help us to understand the people who created the works of art we care for.

Having said that we don't mind a certain amount of chaos, we were delighted to receive a letter earlier this year offering a beautifully organized archival collection, complete in every way and pre-packaged ready for storage. This came from Jo van Montfort, current and indeed final president of the Town and Country Art Society who are winding up their affairs after nearly fifty busy years. This society, formed to promote the joy of painting, often outdoors and often in watercolour, sought advice in that practice from professional artists such as Frank Gross, Bill Sutton and, to come full circle, Olivia Spencer Bower. Artists of this standing also acted as judges in the Society’s painting competitions. Times have changed though and a declining and aging membership has brought them to the decision to wind the Society up. As an incorporated society, they were obliged to do proper accounts, have an AGM and maintain lists of members and activities, all of which have been retained, from their first day to their last. Moreover there are people around who can explain anything that is unclear. This is the stuff of which archivists dream!

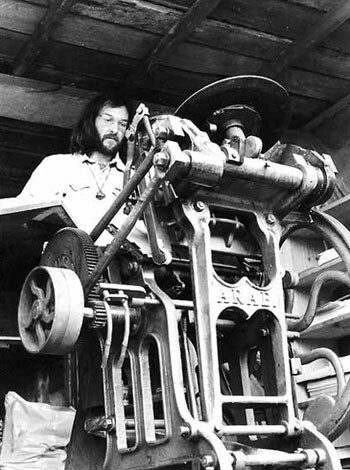

We are the stewards of many other important archive collections, including the archives of the Gallery itself. We have the plans for the Gallery as it was built, as well as the ninety other designs that were not. We have the records of the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, including McDougall's letter enclosing his cheque for £25,000. We care for the artist archives of Bill Sutton, Russell Clark, Raymond McIntyre, Vivienne Mountfort and Barry Cleavin. We are always on the lookout for other archives and we welcome enquiries. Many collections reach us after the death of the person who assembled them, when family members clear a house or studio. But we also have relationships with living artists where we act as a recipient of their material over a longer period of time. In both cases, our motivation is to preserve documents that throw light on an artist's practice.

Not all collections are well-described or well-arranged and we have further preventive conservation, digitisation, and inventory writing to do. Engaging university students to work on these projects has been fruitful. We benefit from having a person focused on a single project, while students are able to handle art historical raw material that relates to their course of study. It is perhaps curious but we find students who are not familiar with a particular artist are often best suited to do very detailed inventories. Having no prior knowledge means that each document is treated equally and with complete neutrality.

The archive collections are never complete. We collect and collect and collect. But while the Gallery is closed we acquire more collections, better describe the documents in our care, and relish seeing researchers use the archive.

The Christchurch Art Gallery Archive collection can be searched using Christchurch City Libraries' online catalogue. We welcome visitors who may wish to view items in the archives by appointment.

Poem with drawings by Rudolf Gopas. Box 7, Rudolf Gopas Archive, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archive, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū