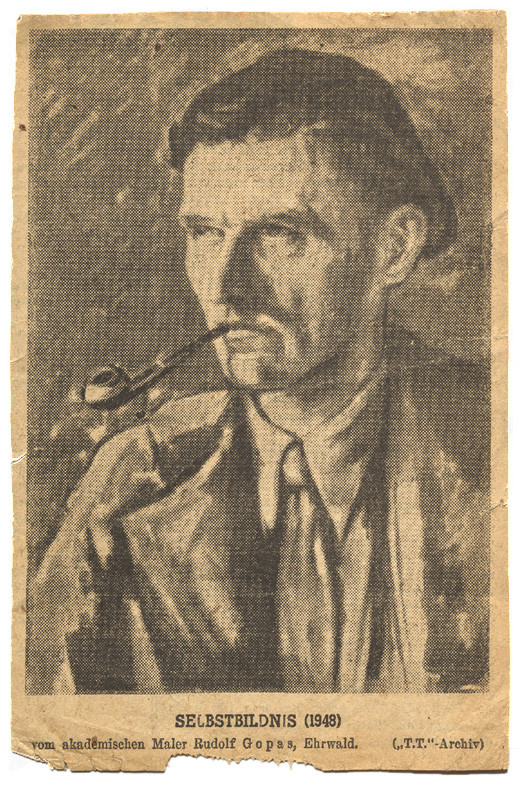

Patrick Pound Portrait of the Wind detail 2012

Patrick Pound, gathering thoughts through things

Based in Melbourne Patrick Pound is simultaneously artist, collector, curator, visual list maker and lecturer in photography. He spoke with Serena Bentley, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Victoria, about the logic of documents and museums of things.

Asked how his practice of collecting began, Patrick Pound reflects, 'I began collecting things to inform my work and what gradually seems to have happened is that the collections became the work.'

He describes his transition from collecting informing his practice, to collecting being his practice: 'I used to make collages more often than I do now. Collage is the limit case of citation. A piece of a thing stands in for itself rather than the artist rendering it. I think the collection works grew out of the slow realisation that the things could and should speak for themselves. I was always rather suspicious of any sort of artful mannerism, and was more interested in the way artworks held ideas I suppose. When you put collected things together they work in a sort of collage anyway. A bit like a newspaper with its peculiar and random juxtapositions.

'Actually one of my earliest collections of images was the collection of thousands of newspaper cuttings of images taken from the daily papers. I liked the idea of the world being delivered to my door, and making art out of that. I cut out photos of people holding cameras, of people holding photographs, and of photos of photos and so on. I also cut out things on fire, people with their faces covered and so on. One huge collection was of people with their arms outstretched. I showed them at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne. I pinned them in a very long row as if they were connected by more than the constraint, there were politicians, actors, sportspeople, magicians, criminals and priests and so on; it was as if they were holding hands. They were joined together by the single constraint of having their arms outstretched.

'I also have albums full of images collected in categories. I also collect other people's albums of images from newspaper cuttings to photo albums. I never break these up though. William Carlos Williams famously said: "No ideas but in things". I'm not sure what he meant exactly, but I know it applies to my work.' Pound pauses, 'To collect is to gather your thoughts through things. I think there is always something of a contest between art and life. For me art is really a way of living—not making a living . . . I like the idea of putting all these recently redundant things back to use—of giving them a new use.'

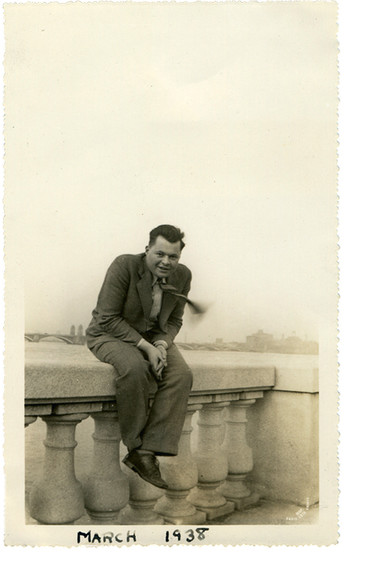

Patrick Pound Portrait of the Wind 2012

‘It will be interesting in the future if and when researchers can access deleted files. It might be rather revealing to look at what people didn’t want to be known by.’

Asked where he sources his materials, and how he stores and catalogues his vast body of found material, Pound explains, 'I get nearly all of my things through eBay. It is a very efficient and thorough way to collect diverse things from diverse sources. I'm also very interested in its sorting, archiving and selling techniques and default habits.

'I store my things in my studio. It's full now though. People say can I come and see your studio. I say, sure we can look through the window. When they get here they realise I wasn't joking. I also have storage in the roof of our house but that's full too. I have hired off-site storage as well I'm afraid.

'Recently I have been working on a few other ways of generating and activating collections via the internet. Rowan McNaught and I made a museum of the middle where things that held some idea of the middle, or the centre, such as Verne's Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Eliot's novel Middlemarch and a postcard of a visitor's centre were then added to, ad infinitum, in the online West Space Journal 1 with links to everything from Greenwich Mean Time to the entire series of Midsomer Murders.

'We recently worked on a website for Judy Annear's The Photograph and Australia at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, where my collection of found photos of images featuring a spherical lens form were sent off into various computer programmes to find similar images and then to draw them onscreen before your eyes, and write them as text on your phone. I'm also now working on a sort of collector's dérive (a rapid journey through different landscapes) where my vast collection of photos of people on the telephone, taken from cinema lobby cards to vernacular snaps, are linked to a mapping app that takes walkers to all the blank spaces where phone booths once stood in Melbourne.'

Pound's collection-based works are generally thematic. Asked whether he has considered bringing objects together using a different rationale or framework, he answers, 'Yes I have. I'm not simply interested in typologies at all. I'm interested in the different ways things might be found or made to hold ideas. I'm interested in the narrative implications of things in series. Some of my collections play on that.

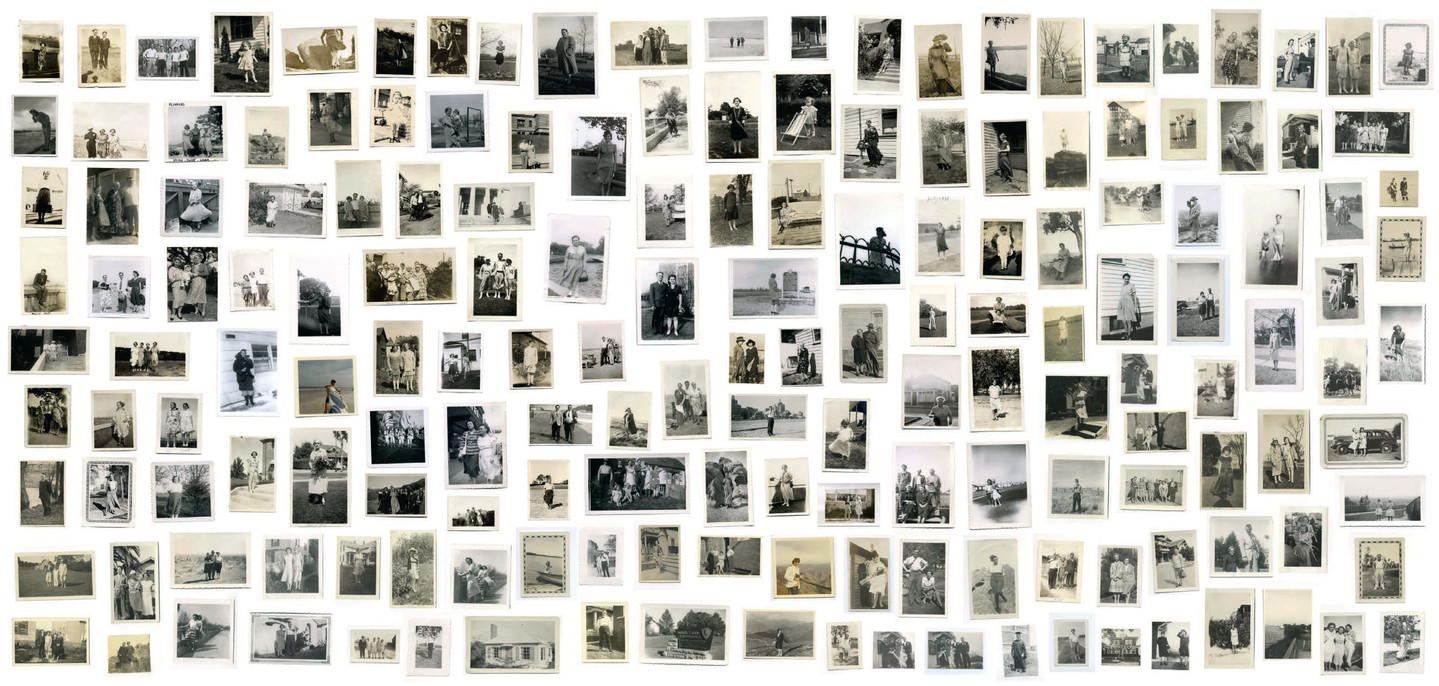

'I'm also interested in how the collection context changes the original and the intended meaning of things. My works sometimes play on that as well. In Korea I showed a huge set of found photos that when put together implied a cinematic narrative of a rather noir detective type simply by accumulation and association. There were photos of movie stars and crime scenes, of houses for sale and discarded clothing. There were crying people and people running. There was a rotting horse's head and a ransom note all in photographic form. Together the implications were clear. The exact story wasn't of course. I called it The Writers' Room.

'I don't usually employ such blatant narrative techniques though. The National Gallery of Victoria recently acquired a huge collection of my found photos of People who look dead but (probably) aren't. The narrative is there too but not in the cinematic manner but in the collected way of successions and resemblances I suppose. It's a more poetic play on the collection as a meaningful accumulation of evidentiary details.

'I am interested in the idea of the literary constraint. This came from Perec and the OuLiPo. Perec famously wrote a novel without the letter 'e'. The basic idea being that a constraint would derail the habits of literary writing and amusingly throw up new and useful forms.'

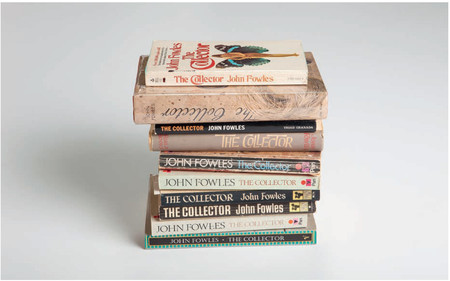

Patrick Pound The Collector 2014. A collection of copies of the novel of the same name

Our growing obsession with and reliance on screenbased technologies, means photographs now often exist only digitally. Pound suggests this has implications for collecting images. 'What photography was, is no more. Daniel Palmer recently noted that photos were once about recording and remembering but the digital turn has largely taken them into the different additional territory—or economy—of experiencing and sharing the experiences of things, 2 Snapchat being the extreme example.

'But on the other hand, the digital age, even in this early stage, means we can search for analogue and digital photographs in totally new and extreme ways. The digital images are also out there waiting to be recuperated but far more often as files rather than physical objects. I collect these files. It's certainly cheaper than buying them.' Pound laughs. He suggests: 'It will be interesting in the future if and when researchers can access deleted files. It might be rather revealing to look at what people didn't want to be known by.' Pound describes the Pagework created for this issue of Bulletin as: 'An extract from an ongoing collection of found and bought photographic images, each of which features a body part, or a sense of fragmentation of the body in pieces. Fragmentation is one of the default positions of the photograph, the camera being a cropping as well as a collecting machine.

'The images are all analogue photographs bought on eBay from numerous sellers in several countries. Some are from defunct newspaper archives, some from discarded family snaps. They are recently redundant images. I'm collecting towards a logic of documents if you will. By collecting within various constraints I assemble otherwise disconnected things. This is something of a poetic and tragi-comic game. The camera reduces the world to a list of things to photograph. The internet is a great unhinged album of vernacular photographs. As Susan Sontag famously said: photographs aren't so much representations of the world as they are pieces of it. 3

'My work treats the world as a puzzle. It's as if we might solve the puzzle if we could find all the pieces. Each photograph is a piece of the puzzle. Each leads to another and another in a relay of ideas. My collection-based works have the look of having been made by someone who on trying to explain the world and having failed, has been reduced to collecting it.

'I'm really interested in how things might be found to hold ideas, and how they might be used to stand in for them. So I have collections of things that hold a single idea. I put them into so-called museums of things. There's a museum of falling, a space museum, a white museum, a museum of holes, and a museum of air. I'm interested in the different ways a thing can be found, and made, to hold an idea. So the museum of air has everything from a bike pump to a fart cushion. The National Gallery of Victoria now holds this collection . . . it goes well with their Jacobean air stem glass and their ancient flutes and their painting of a sheep exhaling misty painted air.'