Wunderbox

Francis Upritchard Wife 2006, and Husband 2006. Rabbit fur, tanned goat skin, modelling materials. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2008. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry

A collection of collections from the collection.

Being an exhibition of bell jars, boxes, cabinets, dolls, display cases, tabletop universes, several bees, two monkeys, hundreds of hooks and one miniature coffin.

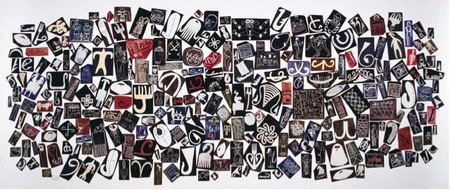

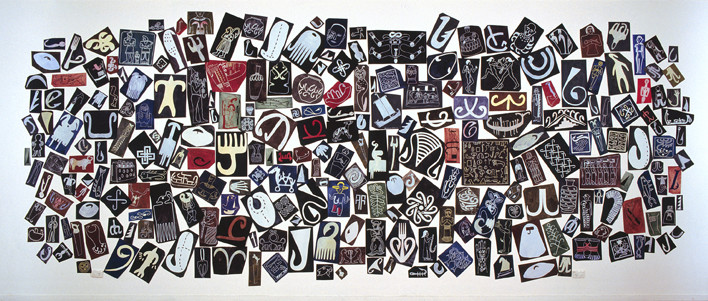

Richard Killeen Book of the Hook 1996. Acrylic on aluminium. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2000

A piece of coral. A unicorn's horn. A clockwork robot. A globe of the known world. Open the doors of a seventeenth-century wonder cabinet and you'll find shelves full of objects like these. Variously known as wonder rooms, cabinets of curiosity and wunderkammer, wonder cabinets emerged in the late sixteenth century and had their golden age in the seventeenth. For patrons and collectors newly fascinated by the world beyond Europe, wonder cabinets offered a kind of portrait of the world in miniature – a finite space filled with a sampling of the world's infinite strangeness.

The most famous wonder cabinets are centuries old, but they raise issues very much alive in art today. Drawn largely from the contemporary collection of Christchurch Art Gallery, Wunderbox is an exhibition of secretive spaces, model worlds, fictitious collections and idiosyncratic dioramas by contemporary New Zealand artists. Ranging from one of the largest works in the collection to one of the smallest, it's an exhibition about our attempts to collect and categorise the world. It's also, more importantly, about the moments of doubt, wonder and pleasurable confusion that arise when the world slips through those categories. Like a walk-in wonder cabinet, the exhibition will unfold through a series of small rooms within the Touring Galleries. In one room, you'll find a tin butterfly in a jar, a wooden box that opens on to a world of symbolism, and a table populated by small glass vessels holding filament-fine dioramas. Further on, there's a bird in a bell jar, a cupboard full of bones, a museum storeroom bristling with trophies and antlers, and, on the largest wall of the exhibition, one of the most remarkable fake collections ever concocted by a New Zealand artist – Richard Killeen's 253-part painting the Book of the Hook.

Richard Killeen Book of the Hook 1996. Acrylic on aluminium. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2000

Most of these artworks date from a period of fervent and sometimes fractious local debate about how best to display and understand objects drawn from other times and other cultures. During a decade when museums were abandoning their old moth-eaten dioramas and politically incorrect display cases in favour of touch-screen interactives and other high-tech options, many of the artists here chose instead to salvage the old display techniques and crank up their strangeness and ambiguity. Thus Terry Urbahn inscribes old National Museum educational display cases with a barrage of mixed messages, while Laurence Aberhart and Neil Pardington discover something haunting and decidedly surreal in museum spaces where order and reason are meant to prevail. Both Urbahn's and Pardington's works dwell on changes within New Zealand's largest ‘cabinet of curiosity', the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Urbahn's display cases were used for educational purposes during Te Papa's former life as the National Museum, but abandoned in the 1990s as embarrassing relics. Pardington's photograph takes us behind the scenes of the current organisation and focuses on the animal trophies that museums once collected in morbidly vast numbers.

From Damien Hirst's preserved creatures to Thomas Grunfeld's topsy-turvy taxidermy, many contemporary artists have been drawn to the stock-still wildlife in natural history museum dioramas. In the alternative museums created by these artists, the usual emphasis on education and explanation gives way to dreamlike juxtapositions, prankster's laughter and lateral chains of association. In two works newly acquired for the Gallery's collection, Francis Upritchard sews a couple of ape-like ancestors from second-hand shop materials, using the skin of one animal to reconstitute another. In the same room within Wunderbox, Judy Darragh gleefully tampers with the usual order of things in a pseudo-serious evolutionary tableaux. Her part-fish, part-human creature recalls a famous hoax creature – the monkey-headed, fish-bodied being known as the Feejee Mermaid. A fossil of the Mermaid was created for American showman P.T. Barnum and sprung on a stunt-hungry public in 1842 in New York, where it was exhibited alongside a creature that, to American eyes, looked equally strange – a platypus. By demonstrating the infinite human appetite for oddity and surprise, inventions like the Mermaid remind us that some of the strangest creatures in museums are not the ones inside the display cases, but those looking into them.

Wunderbox is a collection of works that are themselves about the act of collecting. As the Gallery moves towards a major rehang of its permanent collection in 2009, Wunderbox is also an opportunity to reflect on the ways public galleries accumulate and preserve artworks. The artists in this show leave no doubt about the kind of accumulation they favour: here collecting is a charged and imaginative act with wildly unpredictable outcomes, not a dry and dutiful accumulation of objects. Whether it is Bill Hammond evoking the overzealous efforts of bird-collector Walter Lowry Buller, Zina Swanson sealing insect specimens under glass in her exquisite sculpture Some people's plants never flower ..., or Ronnie van Hout interring a doll-sized version of himself in a tiny wooden coffin, all the artists in the exhibition reflect on what it means to take pieces of the lived world and store them away. Are those things stilled and stifled by this action, or preserved against the ravages of time? Should museums labour to explain and demystify the objects they show, or heighten their wonder and strangeness?

For answers-in-progress, open the box ...

Justin Paton

Senior curator