Meet Me in the Square

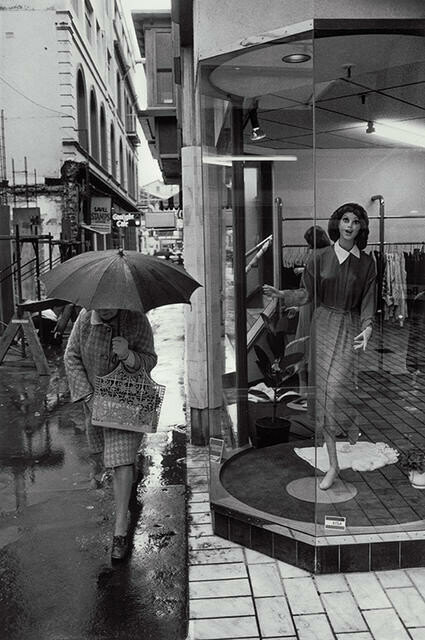

The first thing you notice, even before the pageboy haircuts and oversized plastic spectacles, is the absence of smiles. The unhappiness in the eyes of the average Cantabrian snapped on these grey, chilly streets seems palpable. Even the Christ's College cadet, cradling a rifle as part of soldiery drill, looks ready to turn the gun on himself. In 1983, the year when David Cook began a project to explore his hometown, a camera as his compass, most locals look distinctly brassed off.

Should we be surprised? And was this mood peculiar to Christchurch? The economy was certainly tanking after Robert Muldoon, our most polarising prime minister ever, locked down a Stalinist-style wage and price freeze that lasted for two long years. But things were tough all over: the previous year's beacon pop song, Come on Eileen by Dexys Midnight Runners, provided a cheer-up call to the three-million unemployed in Thatcher's England.

In New Zealand, as in other Western democracies, many of the old postwar certainties were crumbling. The economic regime change associated with the latter part of the decade began to stir as US consultants put the New Zealand Railways Corporation under the microscope. By 1990, the railway workforce, including hundreds who'd come up through the locomotive workshops out at Addington, was slashed to the bone: from 21,000 to 6,000.

The city has always been famously Anglophilic, Eurocentric and white—accused by some of tolerating a quiet racism linked to the absence of Māori, Polynesian and Asian peoples.

A rail workers' fightback is one of a hundred threads in this exhibition, many of which revolve around Cathedral Square. The entry in Cook's work diary for Monday 18 April 1983 is typical of his busy schedule. We read of him racing out to shoot a railways protest march headed for the Square. At its front is a coffin carrying a sign that reads 'Restructuring = Death of NZ Rail'. All assignments are approached with equal fervour: a week later, as Cook snaps soldiers' graves, after ANZAC Day, he doesn't even notice someone pinching his bicycle ('caught bus home', he reports).

For some, a happy memory of 1983 is of the baby Prince William frolicking with a wooden Buzzy Bee toy during a New Zealand visit with his parents, the Prince and Princess of Wales. On the morning of 28 April, Cook is in the Square by 8.15am, ready to snap the ritual mobbing of Princess Diana by huge crowds, timed for 10am. There, he stands shoulder to shoulder with 'school groups, families, police, anarchists, the Wizard—everyone was there. In the rain.'

He continues: 'Royal hand-shaking time. Frenzy... Everyone is so excited to see her. But I realize I'm standing on the south side with Charles, and I can't burst through the police cordon to get over to the action. I manage to shoot Charles instead.'

His images record the expectant, bundled-up crowds in the Square, waving mini Union Jacks and waiting for the royals. The city has always been famously Anglophilic, Eurocentric and white—accused by some of tolerating a quiet racism linked to the absence of Māori, Polynesian and Asian peoples.

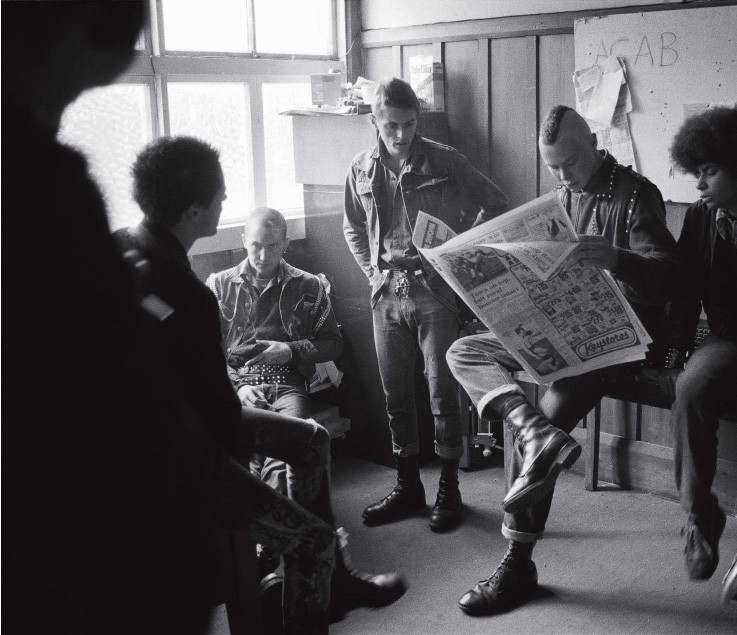

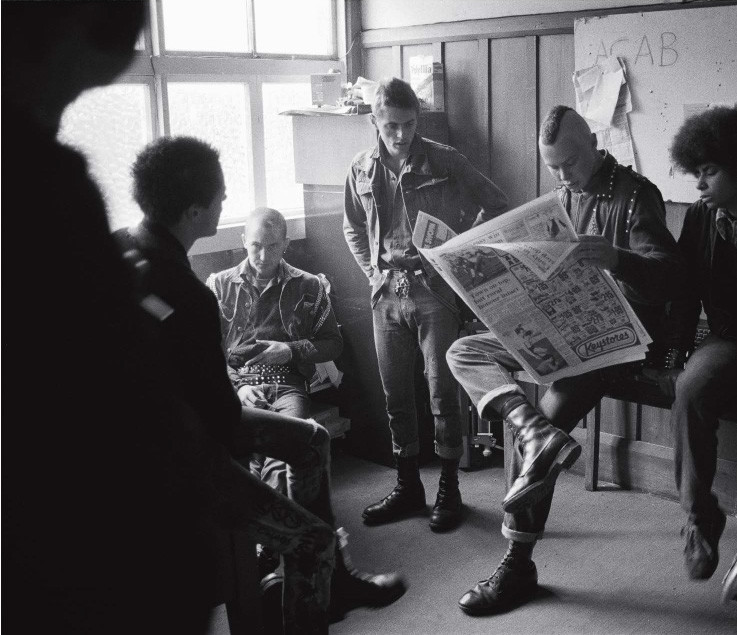

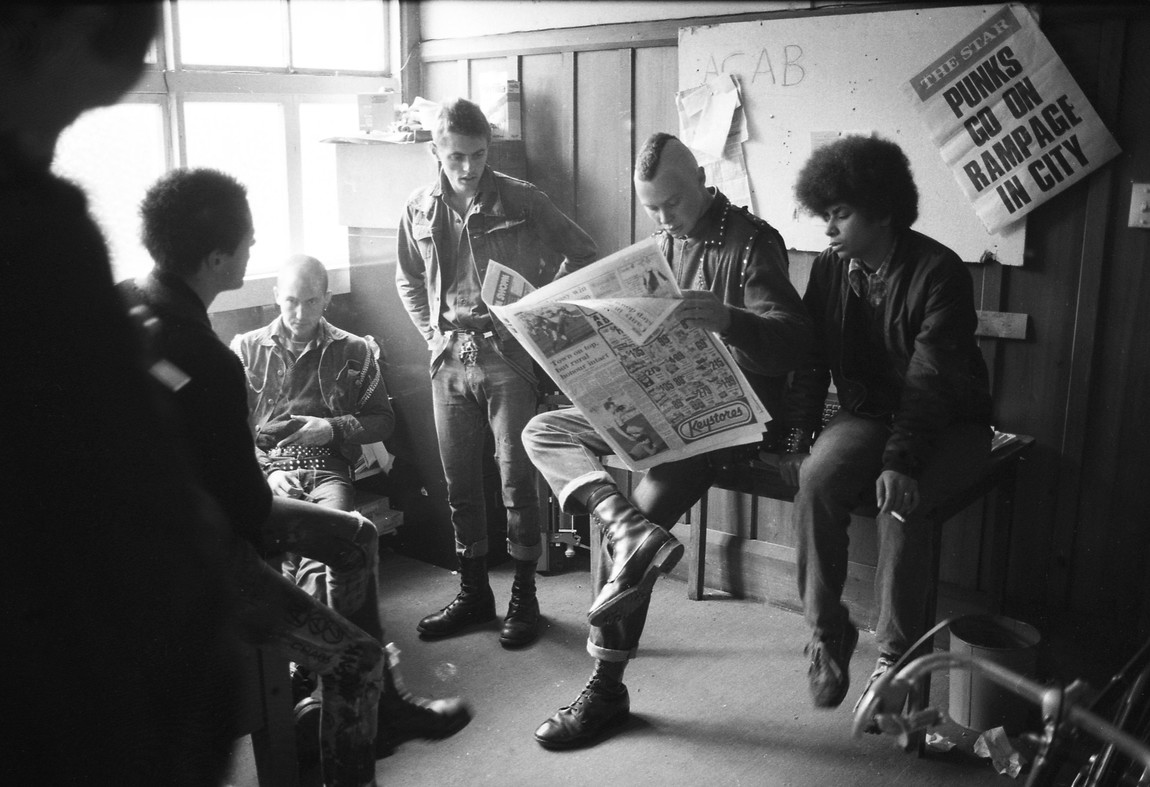

We see the same Union Jack emblazoned on a knitted jersey worn by a local boot boy, an acolyte of a very British, white supremacist subculture that will later become notorious for periodic attacks on ethnic minorities in the city. In 1983, punks would strut and skirmish in and around the Square.

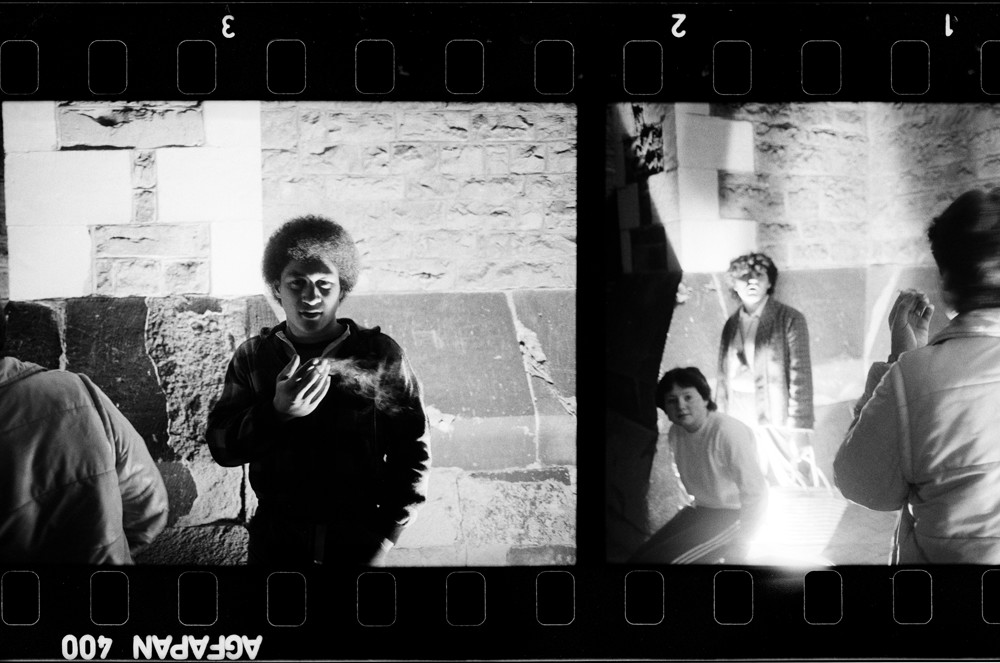

Cook strives, often heroically, to record this significant, if repellent, episode of city history. His diary entry for 17 June records his attendance at a dance in the Caledonian Hall, organised by the Unemployed Rights Centre. Two suitably named bands, the White Boys and ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards), provide the music. He recalls: 'gutsy music ... boot boys, punks everywhere ... it's dark but I try taking photos with no flash—to capture the ambience'.

As ever, our recording angel goes to the wire for his art, narrowly avoiding a beating after he ventures into the street in search of better pictures. Without thinking, he snaps four punks trying to crash start a car.

One guy gets really angry and tries to knock me over—tries to grab my camera. We fight and almost end up in the Avon River. I say, 'Hey man, the flash didn't work. I don't have a photo of you.' Then the police come and the punks run away. Someone tells me I had been photographing then trying to steal a car.

By the 1980s, random violence of this kind would see public spaces in the main centres throughout New Zealand emptying out—with people, especially families not returning. Central Auckland has still not fully recovered from an infamous 1984 riot that saw hundreds rampaging through Queen Street after a free rock concert in Aotea Square.

In Christchurch, crowds were already thinning out in the Square, after city fathers outlawed traffic from the area in front of the Cathedral steps. Newly permitted food stalls, buskers and a cast of eccentrics such as the Wizard and the Seagull Man helped stem the flow. But the crazed, the threatening and the inebriated that flocked there on a regular basis didn't help the cause.

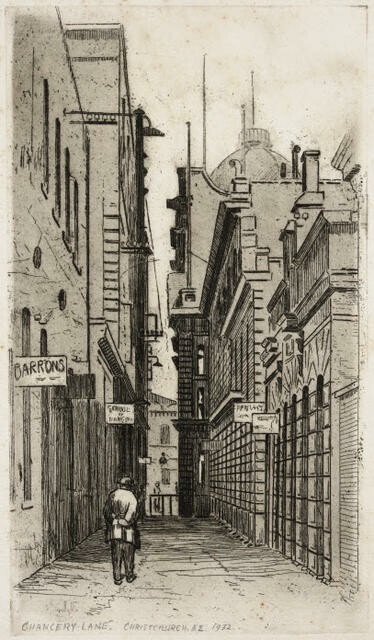

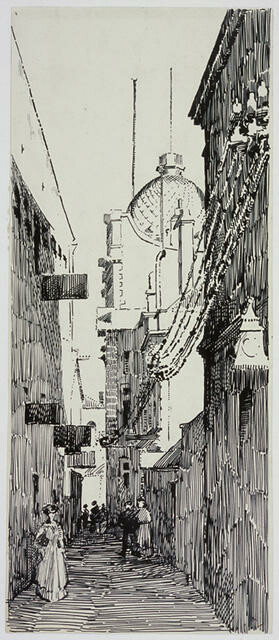

Hatched in the 1850s as city fathers worked to replicate a British-style public space with a cathedral at its heart, Cathedral Square was always one part crossroads, one part menagerie. John Robert Godley, exalted founder of the settlement (despite only actually living there for two years), watched over it all from his bronze plinth. Like other municipalities, Christchurch created open spaces, or what were then called 'lungs'—places where the multitudes in unhealthy, cramped housing could promenade and strut their stuff. By 1900, the Square was lively, even bustling; a magnet for people in a city often mocked as dull and 'churchy'.

The Square was, above all, a transport and entertainment hub. But its status as a mini Hyde Park Speakers' Corner was always a crowd puller. A yeasty variety of political and religious speakers flocked here to lecture the citizenry, probably hoping journalists from the nearby Press Building (opened in 1909) might be taking note. In 1911, the cheeky leftwing weekly Truth, accused the city council of what it called the 'Holy City' of prejudice: banning socialist firebrands from the Square while letting the upright Salvation Army band play on.

The aged and administratively infirm City Council of Christchurch obtained a conviction against Socialist Cooke for spouting in the square on a forbidden spot, after being shooed per by-law over to the north-western corner ... Booth's noisy religionists also refused to leave the forbidden spot but the wowser-ridden Council didn't prosecute.FTN-1

Others flocked to the Square simply to be. In 1914, the new daily Sun, championed the 'seat-warmers' of the Square, helping create its identity as a haven of peace and leisure.

There, the old men sit in the shade or in the dappled sunlight that filters through the trees. All day they sit there, and across the space of asphalt they stare at the United Services Hotel, and the buildings beside it ... they are of the hopeless type; not colonial, though they may be, but men who have lost keenness in the fight, and are content to be discontent and will sit there until the twilight. Presently they will amble off to a home somewhere, and the next day they will be on the seats again.2

By 1929, Truth was calling the Square 'the daily and nightly meeting place for thousands, the starting point for transport services and the point on which the main roads north, south, east and west of Christchurch all converge. To the younger generations of Christchurch, it is tersely referred to as the Square; to the teams of pioneers who cherish memories of the struggles before the province was definitely established, it is revered as the Godley site.'3

The economic depression of 1932 saw violent clashes break out here between striking tramway men employed by the city council and strikebreakers ('scabs') hired to run the trams. Windows on a tram were smashed and a motorman wounded. In May 1945, as war in Europe ended, the Square would be jammed with the largest crowds seen since the end of the Great War.

By the mid 1950s, the Square would play host to another set of 'seat warmers'—the first of the postwar youth cultures that would, a generation later, spawn the angry boot boys who tried to chuck Cook into the Avon. These were the bodgies, widgies and milkbar cowboys: American-styled teenage rebels, who mainly slouched around the Square, displaying what would later be called 'attitude'.

In 1956, a group of psychology students from the University of Canterbury, then located in the city centre, reported on what they called street society in the city ('its chief characteristic was its apparent aimlessness').4 Their study followed publicity about young and restless folk who 'congregated in the streets and in milkbars, some on motorbikes [who] caused obstruction and inconvenience to both wheeled and pedestrian traffic'.5

On the evening of 20 April 1956, six student observers patrolled the city in areas including the Square proper and the streets between it and Armagh Street. Their report said of milkbar cowboys: 'On Saturday evening they were present most of the time between the Square and Armagh Street, outside the Crystal Palace in the Square ... these groups were continually moved on by the police.'6

Their behaviour is forensically recorded:

A group of three youths are lounging outside a milkbar. They are dressed fairly quietly, but wearing 'soft' shoes and longhair styles. A man and his wife are walking by when one youth flicks a cigarette on to the woman and it falls to the footpath. The man tells his wife to walk on; he stops and says to the boy, 'I could twist your nose' ... he lectures the boy on manners, then drags him to his wife several chains down the street and makes him apologise.7

Never again would Christchurch teenagers be as compliant. They'd soon band together, vanish off the streets and head through the doors of venues like the Teenage Club, where rock'n'roll was played at all hours. By the 'swinging' 1960s, as youth culture became a powerful social and commercial force, the city's grooviest venue was centred just off the Square. The Stage Door, at 4 Hereford Street, was where hard-driving, long-haired rhythm and blues band the Chants held sway, as writer Tony Mitchell recalled:

The intense and cramped basement atmosphere of the Stage Door also established it as almost literally an underground bunker beneath the staid parks and neo-Gothic architecture of Christchurch. Chants gigs also took place within a context of running battles be-tween mods, rockers and surfies around Christchurch, sometimes in Cathedral Square, which has long had a reputation for violent encounters.8

The city would soon find itself caught up in the other social and political upheavals of the day. In 1971, more than 6,000 protestors gathered in the Square to voice their opposition to the Vietnam War. A decade later locals would again be here in force, as the 1981 Springbok Tour divided the country.

The space had meanwhile been redeveloped as a pedestrian area, with the south-west section closed to traffic. Over time, the Square became much harder to fill. For some, it was also becoming harder to love. The people of Christchurch, as elsewhere, began to flock to the sheltered, security-guarded shopping malls, often called the modern-day public square.

Redmer Yska is a Wellington writer and author of five works of New Zealand history. His first published news story was about a 1977 visit by Auckland punk rockers to the capital.

But not in 1983. Yet. As punks prowled and a princess from a faraway kingdom twinkled, Cathedral Square still looks like a photographer's paradise. And even if Cook's true interests lay in larger, spikier moments, he made it his duty to record daily life within a built environment that seemed rooted to the spot: eternal, indestructible.

All that would be up for grabs after February 2011, as a great earthquake struck the city, killing 185, toppling buildings and turfing Godley on his bronze ear. And if life during the Stalinist 1980s had robbed the smiles from the faces of the people, things were about to get really grim. The founder's neighbor, Robert Falcon Scott, also brought to his marble knees in 2011, better exemplifies the values of endurance and forbearance Christchurch would have to draw on over the coming years. Associated with the tragic deaths of the explorer and his party, Scott's statue also carries an aura of grief and loss; In 2014, the city, too, mourns those who died and what is no more.

Which is why we relish the warm heart of this exhibition, with its bearded bell-ringers in the Cathedral, cyclists in a sun-splashed street, capped student lighting up a celebratory fag and darkened Press Building. Thirty years on, as a broken city—and its beloved Square—re-emerges, David Cook's quotidian images have a precious, elegiac, reassuring quality that makes us grateful to a snapper ready to lose his bike, even risk a thrashing, to go out and get them.

David Cook: Meet Me in the Square is on display at 209 Tuam Street from 31 January until 24 May 2015, and is accompanied by a new Christchurch Art Gallery publication, Meet Me in the Square: Christchurch 1983–1987.