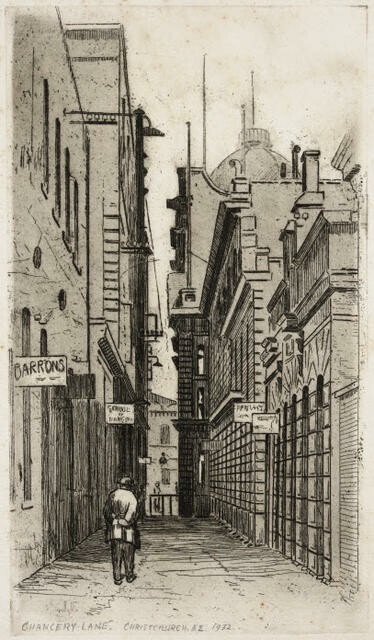

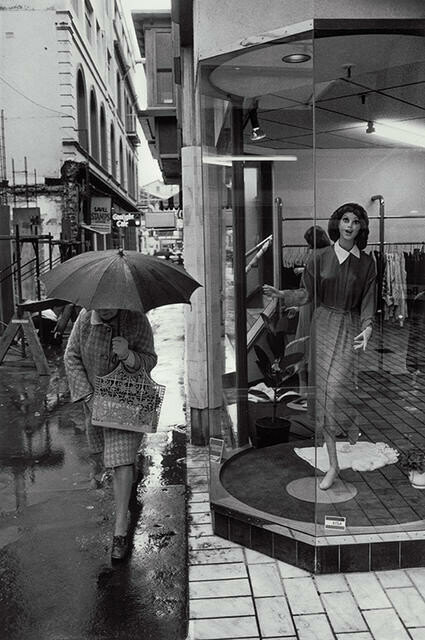

David Cook Christchurch 1983 detail. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

The significance of everyday things

Tim Veling and David Cook discuss the documentary urge and Cook's Meet Me in the Square project.

During the winter of 1984 my mother, father and I packed an overnight bag and climbed into Dad’s Hillman Hunter. I was five years old and, as far as I could remember, it was the first time we’d ever ventured outside of Blenheim.

When we crossed the railway tracks on the way through Riverlands, I leaned forward in my booster seat. 'Dad,' I whispered. He flicked his cigarette out the gap in the top of his window before winding it up. 'We're finally going overseas! We're finally going to Christchurch to pick up Mum's flash new car!' My mother turned to look at me, smiling. Her big hoop earrings swung as we rounded a corner and Dad negotiated a dip in the road. The Hillman Hunter was never the smoothest of rides, certainly not as comfortable as Mum's Corolla turned out to be. 'We're not going overseas, just to Christchurch,' she told me. Dad started laughing. 'Mate, compared to Blenheim, Christchurch is as exciting as it gets,' he said. 'Before the end of the day, we'll be in the Big Smoke. The big city!' I sat back and watched the world rush past my window. 'I hope we have time to look in Ballantyne's,' Mum said. 'Or at least climb the Cathedral spire. You'd like that, Tim. You can look out over the whole city. It's so high all the people in Cathedral Square look like ants.'

Unfortunately, we didn't have time to explore Christchurch at all. We lost an hour or so parked on the side of the highway while I stared at the bottom of an old ice-cream container, regretting the Mello Yello I'd downed at the service station in Ward. Mum sat in the front seat. 'Next time we do this, we should stay a few nights,' she said, as Dad stood watching me from outside, checking his watch and sighing.

We eventually arrived in Christchurch after dark. Mum picked up her new car while I slept in the hotel and we left for home again before first light. Mum didn't get to browse the racks in Ballantyne's for another eight years – we moved to Christchurch in 1992 – and despite the best of intentions, I never did climb the Cathedral spire.

I remember all of this when I sit down to contemplate Meet Me in the Square, a new book of photographs by David Cook, published by the Gallery. The images within it were taken between 1983 and 1987 and, as David mentions when we talk, the cover image was taken around the time I first visited Christchurch.

David Cook. Photo: Tim Veling

David Cook: That photograph was taken in 1984. It was my first year out of the University of Canterbury, where I'd gained a Diploma in Fine Arts. I'd originally gone to art school to become a designer or a painter, but I became obsessed with the photographic medium and its power for storytelling. I had been an awkward, painfully shy and quiet young man, and the camera gave me an excuse to explore and engage with the world. Finding photography was incredibly liberating for me.

For my end of diploma assessment I'd submitted a body of work on Christchurch city, but found I was hungry for more. The work just didn't seem complete, so I kept photographing for years after graduating, even after I'd moved to live in another city.

Tim Veling: How did you find yourself up Christ Church Cathedral that day? What were you looking for and what was your intention for being there? I ask this because, years after it was taken and after the earthquakes, the photograph now seems very loaded; what might have been considered a relatively sentimental image of a sleepy city centre now conjures up quite potent and mournful feelings of place and time.

DC: I was always challenging myself to try and see the city from different vantage points. I wanted to try and bring to light the significance of everyday things and to prompt people to think differently about familiar surroundings.

I can't remember exactly why I climbed the spire that day – I often photographed in and around the Cathedral – but I was struck by the shadow and the way it moved across the space; the way people walked through the shadow without knowing or thinking about how they were in its space.

David Cook Christchurch 1984.Photograph. Reproduced courtesy ofthe artist

‘I’ve left behind that concern about the single, heroic image and tried to find ways to immerse the reader in a kind of experience of the city.’

TV: This is a city built around an Anglican cathedral. In this picture, the shadow of the neo-Gothic spire does seem quite oppressive.

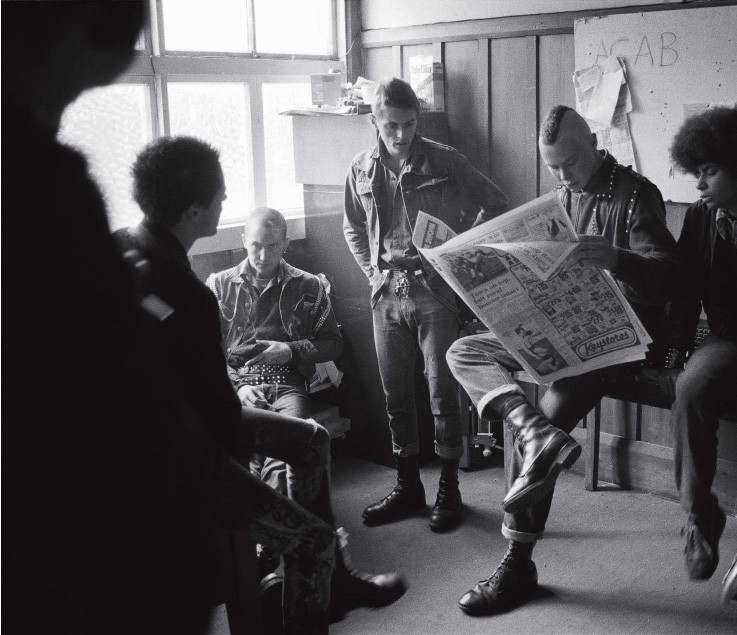

DC: There is more in the picture, though. There's a preacher standing on a little step stool, right in front of the tip of the spire's shadow. There are men lounging in the sun – I think they're topless – and a group of punks in leather jackets. There's a businessman wearing a suit and tie and carrying what looks like a manila folder. There are couples walking together with shopping and the shadow of a seagull that's flying above, outside of frame. I guess I enjoyed the pattern of the bricks and the shapes and forms they presented, too. The scene must, at the time, have reminded me of Rodchenko's photography.

You asked me what my intentions were for my work. I grew up a member of the Salvation Army – a Salvationist. That meant, for me at least, Christchurch was a safe but very interesting place. The Salvation Army was located in the city and because of that I had been exposed to all sorts of interesting aspects of social work. I had encountered people on the streets from all strata of society. As well as giving me a good sense of tūrangawaewae, those encounters gave me the interest and hunger to go out and investigate society on all sorts of different levels. Ultimately, I wanted to depict those social layers within my photographic work.

TV: Perhaps we could talk about issues of influence and art school. You said you initially wanted to become a designer or painter. Back then, there were some big personalities teaching at the School of Fine Arts. How did they influence the way you went about making your work and the possibilities you saw for yourself within the medium?

DC: There are big gaps in this conversation. I can talk about art school, but I should also mention I studied photography after gaining a degree in botany. I loved scientific fieldwork. I especially enjoyed doing transects and building an impression of the ecology of a place; how a place changes over time and space, day and night and seasons. From there, I developed an urge to work in the visual realm. I went to night class to study art and eventually enrolled at Ilam.

Initially I was taught by Glenn Busch, whose deeply serious influence was the idea of just stopping, pausing and spending time reading photographs – I mean, really critically looking at the relationship between content and form. I remember him showing me Bruce Davidson's East 100th Street and the light went on. I thought, yeah, this is what I want to do.

In my second year, wham! Larence Shustak was back on the scene after a year's sabbatical. That was the best and worst thing in the world; he was an immense provocation to me. He was an intense guy and I needed to be shaken up – I was very much in danger of being really conservative in my approach to the medium. Larence was a crazy New Yorker who oscillated between a stoned 'I don't care' kind of attitude, and a macho critical style. He made me an independent photographer because he was someone to fight against. Ultimately, he liberated me to look and try harder to develop my own voice.

TV: I'm asking these kinds of questions because I think when analysing photographs, especially those that depict what we might politely call a bygone era, it's important to understand the broad context in which that work was made. In that sense, I think one of the great things about Meet Me in the Square is that it reads like a re-exploring of old, archived material. The way it's put together; it's a series of half-truths and fragments of memories. I get the sense that you have been a lot looser with the material from your archive than you would have originally intended when making it.

DC: I always intended to make a book and exhibit this material. At one point in the 1980s, I actually did have a small exhibition of twenty photographs at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery. Back then I was looking for that Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank kind of image. I was looking to capture those moments when all the visual elements come together in front of the camera to say something poetic about time, place and life. I was mostly concerned with the artistry of making good, single images. That's how I edited my work.

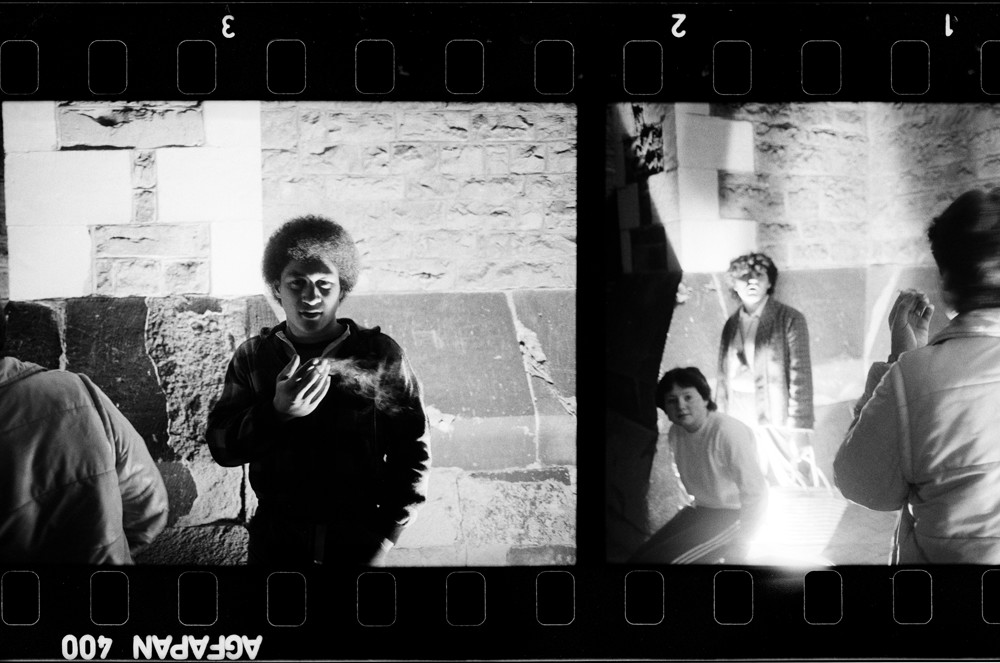

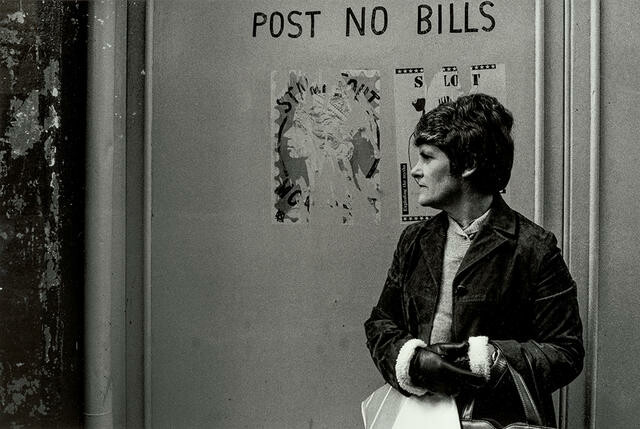

Years later, I don't feel a need to prove myself as a photographer any more. I've left behind that concern about the single, heroic image and tried to find ways to immerse the reader in a kind of experience of the city. I'm thinking about things like graphic novels or the Japanese Provoke photobooks. I want people to consider the materiality of the raw content and the book as an object in its own right; for it to be an experience in itself. I want people to feel like they are digging into a whole stack of proof sheets with me, looking at them with various levels of scrutiny. From close ups, to standing back and looking at joining negatives on strips of film. I've tried to encourage a reading of peripheral details and of things happening just outside of the frame. This meant being open about technical mistakes, like bad exposures or focus errors, all for the sake of conveying something more faithful to my sense of exploration back then.

Pages from David Cook, Meet Me in the Square: Christchurch 1983–1987, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2014

TV: That's one of the things I like about the book. When I sit down and analyse all the little details and think about the way it's put together, I sense the development of a young photographer. I sense someone working with intention, working their way in to moments with the camera, then working their way out of them.

The overall final impression is not only of a city in flux, but also of you learning your craft.

DC: Yes, throughout the book I can see myself asking questions and experimenting. Glenn introduced me to that humanist side of photography, then Larence introduced me to provocative photographers like William Klein, who'd use the camera almost like a weapon. In my own way, I'd try to do things to replicate those models of working. Some days I'd stand back and observe things happening, and on others I'd ambush people and press click.

TV: I'd like to talk about your body of work, Lake of Coal. I opened the interview asking questions about your Cathedral spire photograph because it effectively frames Meet Me in the Square as a body of work to be considered with reference to what we've lost. In 1984, you could never have foreseen this. With Lake of Coal and the work you made in Rotowaro, however, you set out to document the loss of a community from the outset. Unlike your work in Christchurch, there was a very specific and charged story to follow.

DC: I started Lake of Coal as a year-long commission for the Waikato Museum – part of a larger project that looked at the impacts of energy developments in the north Waikato region. I chose Rotowaro because of the potent story and, after the commission finished, I found various ways to fund and continue making work.

With Rotowaro I could see the whole story unfolding in front of me. It was in some ways a classic piece of storytelling for an ethnographer or photographer. There was incredible upheaval, both in terms of the social and the physical environments. I hung in there and developed strategies to be able to express and reflect on all that was happening. I harvested words, images and documents to try and tell that story. I mean, I had seen a lot of stuff in museums and books that was all about salvaging relics of history and trying to rebuild things, but here I had the opportunity to actually be in the moment and to collect information as things happened.

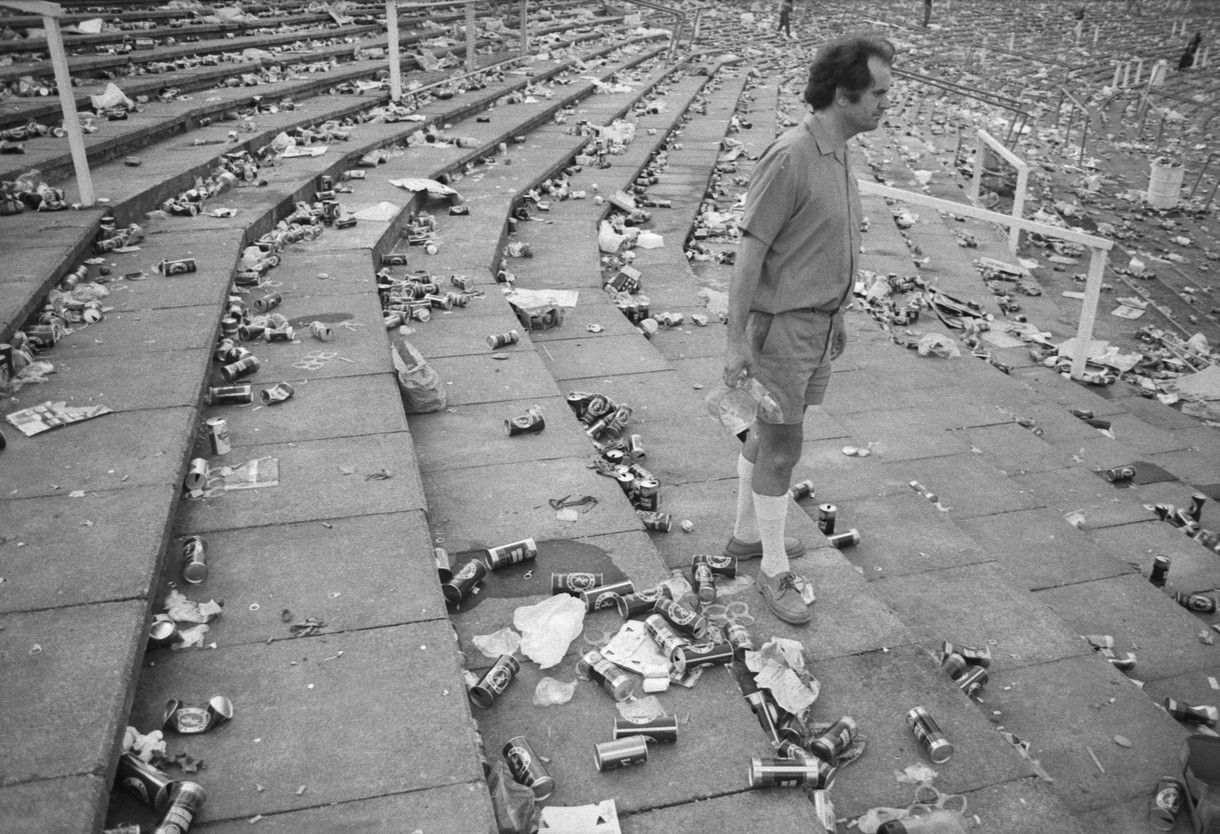

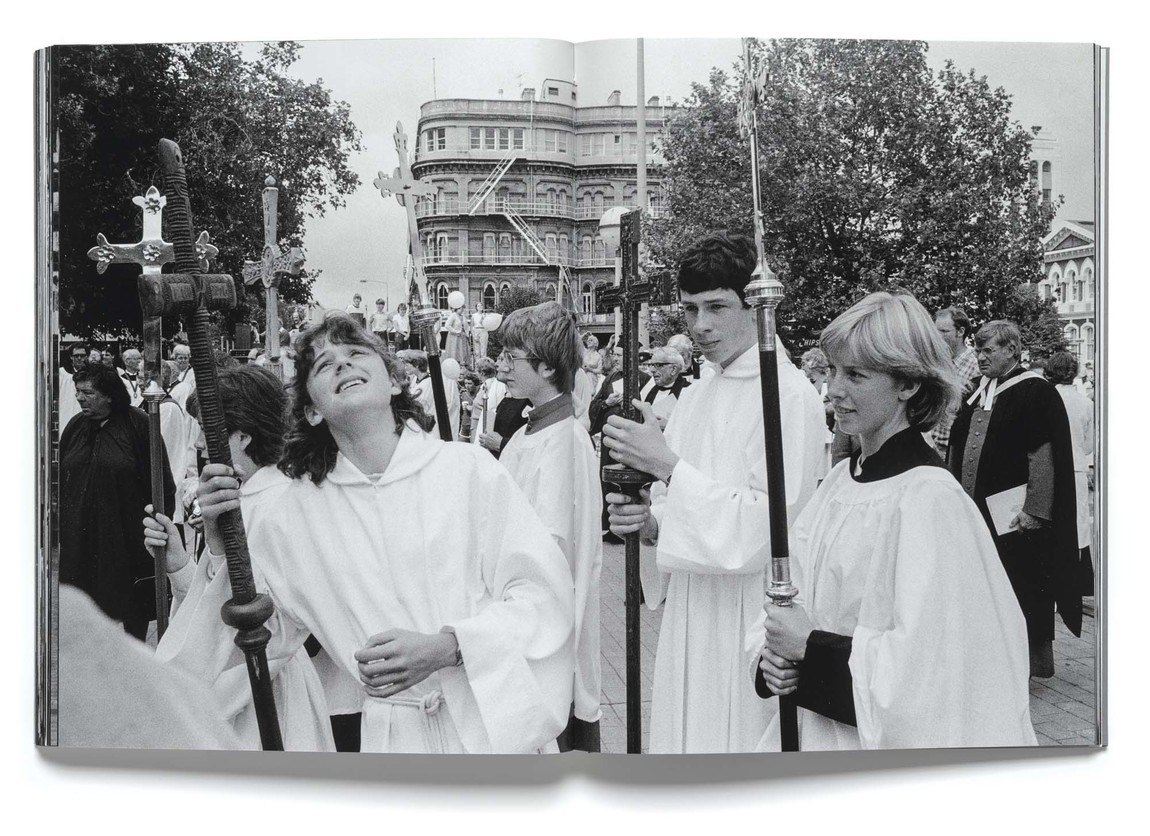

Pages from David Cook, Lake of Coal: The Disappearance of a MiningTownship, Craig Potton Publishing, 2006

TV: Again, what strikes me with Lake of Coal is that when you pick the book up, you're instantly aware of the purposeful way in which the content is presented and sequenced. There are some amazing spreads containing images that depict the community and its people above ground, with images of miners carving tunnels beneath those people's homes and streets. By way of forcing people to engage with the book in this way, the reader can begin to understand something of the sociopolitical and commercial conflict playing out.

DC: I didn't want to convey an experience of sifting through an archive of material with weepy eyes, full with sentimentality. I never took the photographs as curious images of the past – I have always been more interested in the here and now. To me, they were images with currency, of things I was seeing happening around me and affecting a lot of people. With Lake of Coal, I wanted to create a record of what was happening, but I also wanted to invest that here-and-now currency into the book. By way of editing and design and reflexive story telling – bringing my reflections on my role as documentary maker into the work – I wanted to make that story feel real for the reader.

Coming back to my image of the Cathedral spire, I always intended to go back up there and spend an entire day photographing the shadow as a sundial, moving across the square. I wish I could go back in time and do it.

TV: Perhaps they might rebuild the Cathedral. If the Anglican Church choose to restore it, maybe you will get another chance?

DC: I don't live here any more and that is a very contentious story. I'll avoid voicing an opinion on it.

TV: Well, if they do, perhaps I can photograph it for you. I always wanted to climb up there, but never took the time to do it. One thing's for sure though, if they did I'd see a very different view of the city.