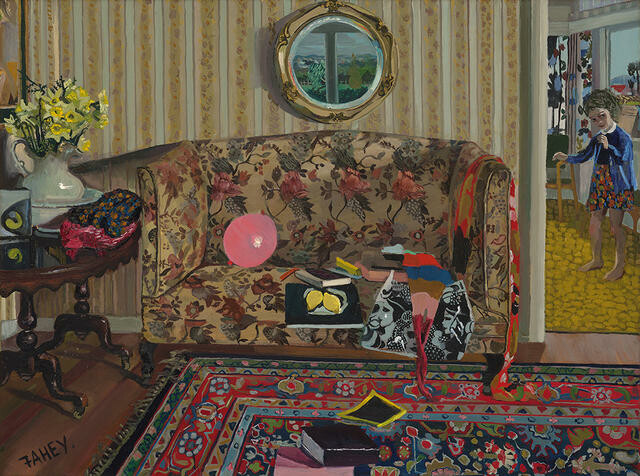

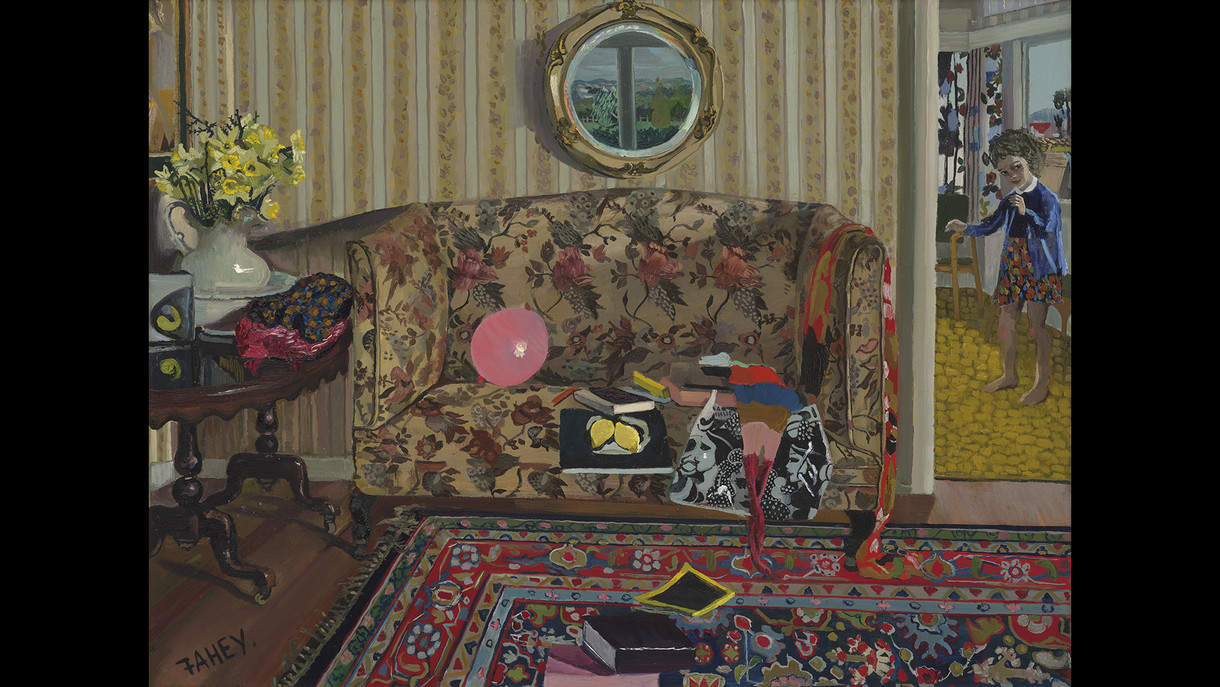

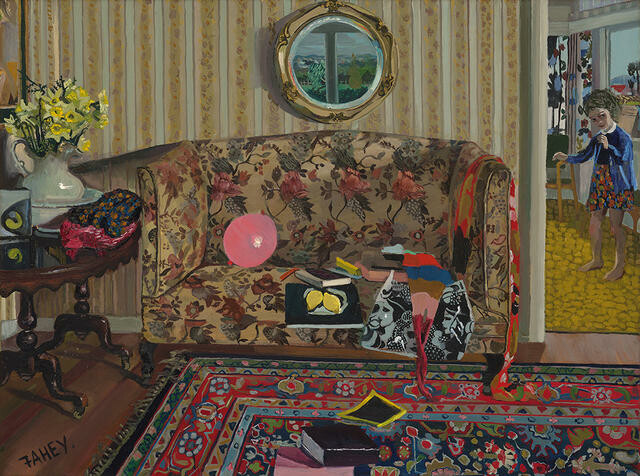

Jacqueline Fahey

Aotearoa New Zealand, b.1929

The Portobello Settee

- 1974

- Oil on board

- Gift of the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, 2017

- 1020 x 1325mm

- 2017/089

Tags: balloons (toys), books, carpets, children (people by age group), curtains (window hangings), floors (surface elements), flowers (plants), girls, interior, mirrors, natural landscapes, patterns (design elements), sofas, stripes, tables (support furniture), toys (recreational artifacts), vases, wallpapers, windows

“I think a lot of painters of my era have a hangover from art school days. If you could pull a painting off without a pause – no having to backtrack, no laborious re-worked areas, no long delays to work out the next move – all of it effortless, then you inspired the admiration of the other students. I think it was a sort of sympathetic magic: if the artist enjoyed painting it so much then people must enjoy looking at it as much […] This painting belongs with that kind of response – it just went like a bird. I felt certain of my vision, certain I could endow my humble objects with mana because for a while they were totally beautiful to me. My need to record was intense, innocent and certain. No intellectual calculations crept in to cloud my vision. It was pleasure all the way through. I know this is a form of art snobbery. I know I have done other paintings equally good which arrived agonizingly slowly, calculated every inch of the way and very like a game of chess in the thinking out of each move. However, The Portobello Settee is my choice, I suppose because we don’t escape our old values easily”– Jacqueline Fahey in Say Something, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2017

(Perilous: Unheard Stories from the Collection, 6 August 2022- )

Exhibition History

(Persistent Encounters, 10 March 2020 – 19 September 2021

The underlying influence of Dutch Golden Age painting is unmistakable in Jacqueline Fahey’s The Portobello Settee, particularly when seen alongside Gerrit Dou’s The Physician. Similar motifs appear in both works, from draped fabrics and Turkish rugs to books, bowls, windows and repeating circular forms. The small girl’s pose and expression also echo that of the waiting figure in the background of The Physician.Although painted over 300 years apart, both works can also be read as meditations on existence. Dou’s meticulous work considers a lifespan from conception to death, while Fahey’s painting brilliantly assesses the contained disarray of the place and time in which she finds herself; her immediate environment and experience as a mother in early 1970s Aotearoa New Zealand.

We do this, 12 May 2018 – 3 June 2019

Faced with juggling the competing roles of mother, housewife and artist, Jacqueline Fahey made her everyday environment an integral part of her art practice. “I decided that instead of getting away from it all, I would embrace domesticity; transform it, interpret it. Who better than someone immersed in it?” Fahey’s works of the 1970s captured the private spaces of her family home, exposing all the inconvenient realities – messy couches, overflowing washing baskets, unruly children – often absent from conventional paintings of domestic scenes. By drawing attention to the ordinary objects and daily routines that were part of many women’s lives, she contributed to the increased visibility and understanding of female experience. “I could endow my humble objects with mana”, she said, “because for a while they were totally beautiful to me.”

Jacqueline Fahey: Say Something! (22 November 2017 – 11 March 2018

'I think a lot of painters of my era have a hangover from art school days. If you could pull a painting off without a pause – no having to backtrack, no laborious re-worked areas, no long delays to work out the next move – all of it effortless, then you inspired the admiration of the other students. I think it was a sort of sympathetic magic: if the artist enjoyed painting it so much then people must enjoy looking at it as much […] This painting belongs with that kind of response – it just went like a bird. I felt certain of my vision, certain I could endow my humble objects with mana because for a while they were totally beautiful to me. My need to record was intense, innocent and certain. No intellectual calculations crept in to cloud my vision. It was pleasure all the way through. I know this is a form of art snobbery. I know I have done other paintings equally good which arrived agonizingly slowly, calculated every inch of the way and very like a game of chess in the thinking out of each move. However, The Portobello Settee is my choice, I suppose because we don’t escape our old values easily' - Jacqueline Fahey.