Safe Houses, Comfort Zones

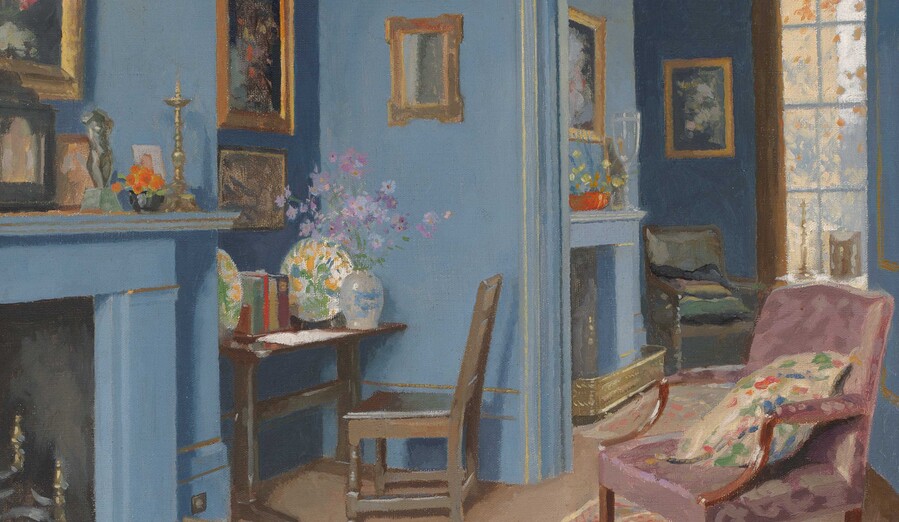

James Durden A Blue Room in Kensington (detail) c. 1930. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by a group of Christchurch citizens, 1932

In an age of crisis and pandemic, our basic human need to remain safe has seen living spaces transformed into protection zones and shells to pull back into. So it is perhaps unsurprising to see pictures of domestic interiors charging up differently, re-emerging as sites of refuge, confinement and familiar disarray. Here curator Ken Hall looks at two works from the exhibition Persistent Encounters.

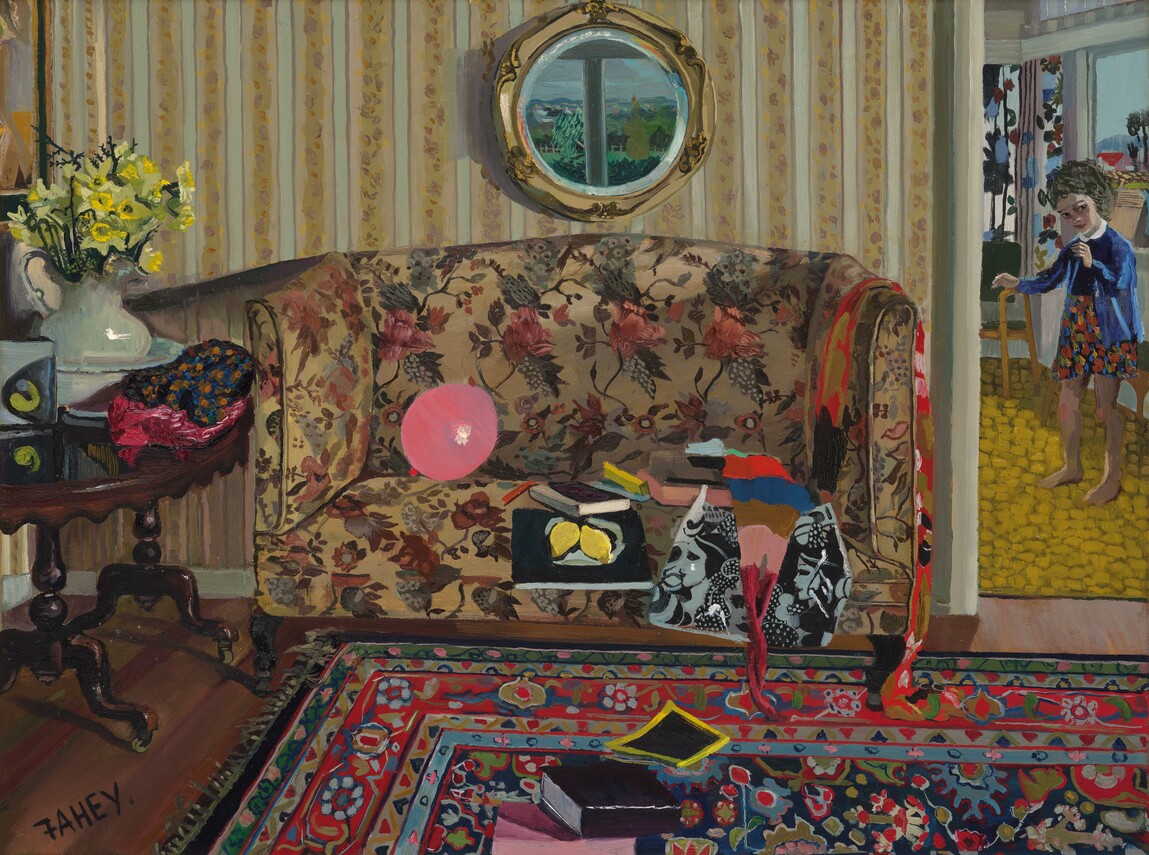

James Durden’s well-appointed central London room and Jacqueline Fahey’s corner of her home in Auckland were painted decades apart, but they share much in common. As an easy start, each pictures one space leading into another, light entering from two directions with windows implicit on both sides.

Rising success had seen the Northwest England born Durden moving from predominantly working class Hurlingham, south-west London to take up residence at the upmarket Ladbroke Square in Kensington in about 1930; this may have been his family’s new home. Beyond his bluebell-tinted walls, a high sash window frames yellow leaves, positioning him on an upper floor. Fahey was also in a new environment and her windows frame a higher elevation. One of her two views, seen in the central, circular gilt mirror, places her above the stretching suburb of Mount Albert, where she and her family had just moved from Kingseat, south of Auckland.

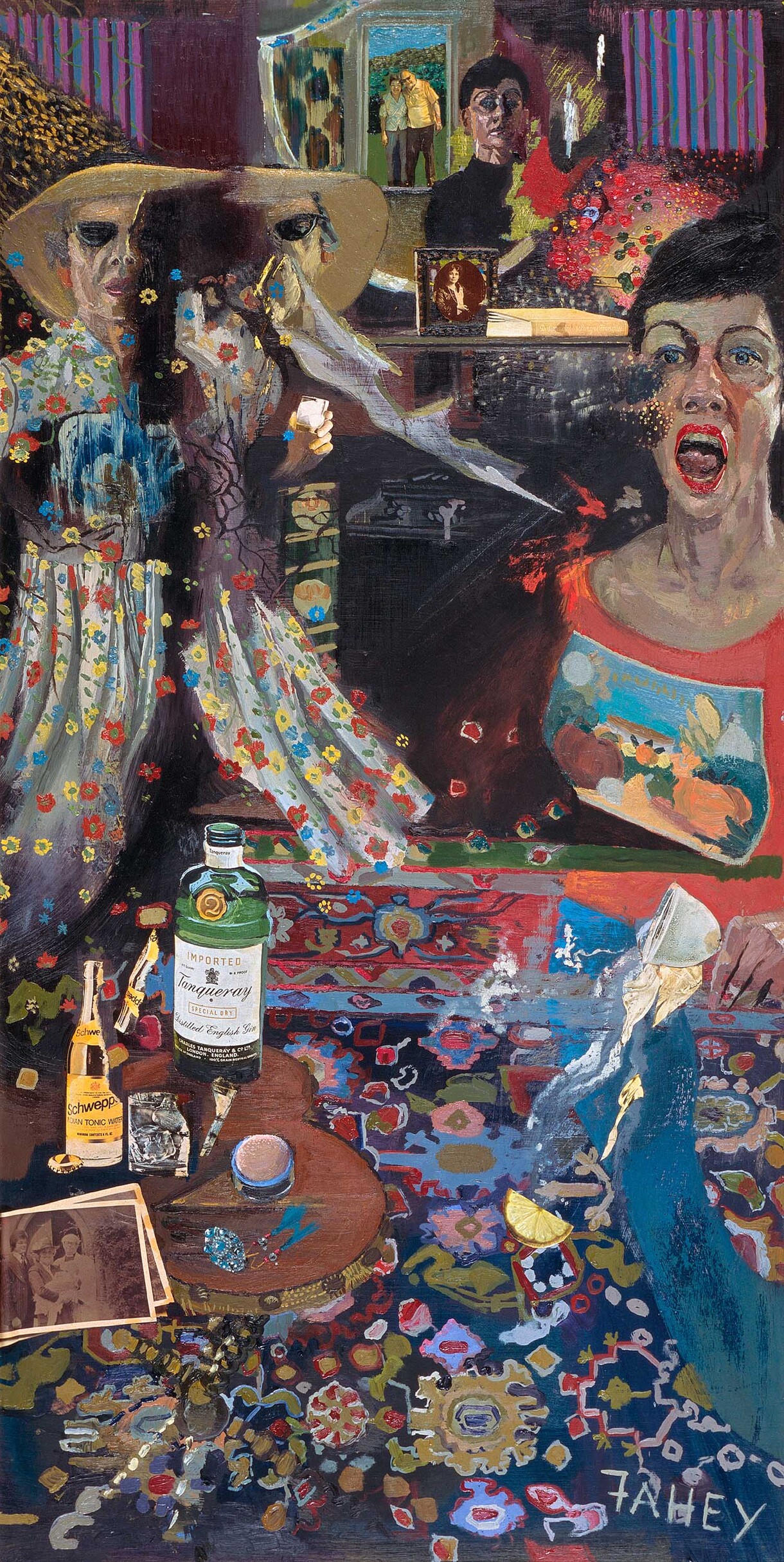

A Blue Room in Kensington and The Portobello Settee hold many smaller overlaps. Each room is filled with carefully selected furnishings, chattels such as Turkish rugs, mirrors, pictures, side tables and chairs. There are books and reading material, neatly stacked or strewn in temporary disarray. Fahey’s room shows greater evidence of life being lived in its normal messy way, with pink balloon, scarves and assorted family jumble. Emily, the youngest of her three daughters, is seen poised and waiting through a doorway. Fahey’s monolithic couch – 1920s, original upholstery – had been dubbed a “Portobello settee” by the Parnell antique dealer from whom she bought it. These are both spaces where attention has been given to simple aesthetic pleasures and comforts. Durden’s work incudes delicate flowers in a porcelain vase and smaller posies; Fahey’s gives us daffodils in a Victorian wash-jug. Both include dark-stained wooden tables, similarly shaped and positioned. The people who used these spaces, we might easily recognise, were privileged to be able to create havens and inhabit places from which the rest of the world could be temporarily shut out.

In our own post-lockdown moment, Durden’s painting appears the most cocoon-like; the sense of refuge it embodies perhaps extending to keeping modernity at bay. An admiring Liverpool-based critic reviewing his work in 1922 had seen him as a member “of the objectivist-decorative school whose hold on British artists has lasted so long and which has been so little challenged”.1 Embedded in her evaluation was quiet commentary on the industrial north, as she noted “Mr. Durden’s chief trait in common with other Manchester-born artists is his adherence to light, clean colour and other qualities foreign to Lancashire.”2 James Durden occasionally painted other interiors, sometimes opulent (his first to reach New Zealand, incidentally, arrived in 1930 after its recovery from a shipwreck between Dunedin and Bluff),3 but his speciality was striking portraits of elegant young women, which he lined up for the Royal Academy. His most frequent model was his daughter Betty, and he painted her in chinoiserie settings of lacquer and shimmering embroidered cloth (with pet chow-chow in Betty and Chu, shown 1928); and in sunlight through open terrace doors (A Balcony in Kensington, shown 1931). These were dramatic and decorative, vaguely aristocratic, perfect for attracting commissions, conveying nothing troubling or harsh – the mindset of the day would have seen little problem with Betty (shown 1927) reclining on a polar bear skin rug.

James Durden A Blue Room in Kensington c. 1930. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by a group of Christchurch citizens, 1932

Durden’s world – as with the worldview that brought his painting here – still held London as the centre. His pictures disclose a perceptible sense of gratification at his own rise, achieved through application to his art. Born in 1877 in the middle class suburb of Chorlton in Manchester, where his father was a maker of clothing samples, he had studied at the Manchester School of Art before winning a scholarship to the Royal Academy School in South Kensington. He married Ruby Valentine Ellis in 1907 and supported a young family through years of book illustration and painting. After the outbreak of war they moved to Orchard House, Whitehaven, Cumbria, which was peaceful enough until a German submarine launched an attack on a nearby munitions ingredients factory in 1915 (the aftermath of which he painted). Durden signed up for military service at nearly forty, was sent to Boulogne in 1917, worked in supplies depots in the Army Ordnance Corps and returned home safe at war’s end. The move back to London came shortly after a 1922 Studio article, and a second property was maintained at Keswick in the Lake District. Durden’s quietly respectable kind of English artist’s life included occasional travel to Italy and (with Betty’s marriage to an Australian-born painter) a visit to Cape Town in 1934.

A Balcony in Kensington reached New Zealand not long after it was painted, as one of three of Durden’s works selected for a touring exhibition of British contemporary art. It was purchased in 1932 for 25 guineas, raised by public subscription – a gift for the city’s new Robert McDougall Art Gallery collection. Jacqueline Fahey’s The Portobello Settee was gifted in a similar way, purchased with generous support from the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery. Entering the collection during her much enjoyed exhibition here in 2017, it is an important early work that the artist had retained.

Fahey has been a painter for seven decades, and easily invites respect, not just for her stands-tall-in-the-forest status. Born in Timaru in 1929, she started at the Canterbury College School of Art in 1946, where she was taught by artists including Russell Clark and Bill Sutton, and influenced by artists including Doris Lusk, Juliet Peter and Rita Angus. She first met Angus at Sutton’s studio in 1950, and in the following year moved to Wellington and married psychiatrist Fraser McDonald. As they began to raise a family, Fahey had to negotiate her own creative path through this new reality. After an energising year in Melbourne in 1960, they returned to Wellington, where she befriended Angus, and with her in 1964 coordinated New Zealand’s first deliberately gender-balanced art exhibition at the Centre Gallery. In the following year Fahey and her family relocated to south of Auckland; her husband took up the role of superintendent at Kingseat Psychiatric Hospital. Increased clarity in Fahey’s direction came in 1970 with the death of her father:

[I] was gripped by an urgent pull. I understood my immediate life was my inspiration. The mess on the table, the dishes, the unmade bed, all took on an aura of profound meaning. My mother visiting, the gardener working outside, the children dating, drinking, thinking. When these paintings were exhibited, I was called a domestic painter – but domestic painters in the past had tidied up their houses first or, I assumed, their wives had. I was making the mess visually lovely, taking the gentility out of the genre.4

Jacqueline Fahey The Portobello Settee 1974. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, 2017

The setting at Kingseat was anything but genteel. While McDonald was making inroads in changing approaches to psychiatric care, including pioneering group therapy treatment, Fahey sidestepped the strictly defined superintendent’s wife role and set up painting classes for young, mainly Māori, women; she sometimes saw students dislodge unimaginable horror and trauma through their work. Stepping further beyond passive comfort zones, she fought for proper attention to be given to desperate, abandoned children, and in doing so gathered both strong allies and detractors.5

Fahey painted The Portobello Settee not long after their next move, in 1974, to Carrington Psychiatric Hospital, where on-campus staff housing became their home for the next sixteen years. Deeply connected to her everyday experience, it reflects her bold spirit and strong-hearted outlook, anchored also by the articulate realism with which she chose to communicate. A work filled with beautiful passages in paint – concentrated flows of energy, pattern and movement – it is also one she later described as having come together painlessly, matching ideals that many artists of her generation held in high regard.

I think a lot of painters of my era have a hangover from art school days. If you could pull a painting off without a pause – no having to backtrack, no laborious re-worked areas, no long delays to work out the next move – all of it effortless, then you inspired the admiration of the other students. I think it was a sort of sympathetic magic: if the artist enjoyed painting it so much then people must enjoy looking at it as much (...) This painting belongs with that kind of response – it just went like a bird. I felt certain of my vision, because I could endow my humble objects with mana because for a while they were totally innocent to me. My need to record was intense, innocent and certain. No intellectual calculations crept in to cloud my vision. It was pleasure all the way through.6

The Portobello Settee is one of Fahey’s most remarkable works, and still feels much like real life. Although less a sanctuary than A Blue Room in Kensington, it nevertheless similarly conveys a sense of refuge and celebration of the moment in which the artist finds herself. The moment may be naturally fragile and short-lived, but is expressed with pleasure and strength. There is a greater expression of warmth and brightness here than there is a feeling of yearning for stillness or escape. In our own present moment, both paintings speak to our need to find shelter against an often confronting or distressing world outside.