Down the Waitaki Awa

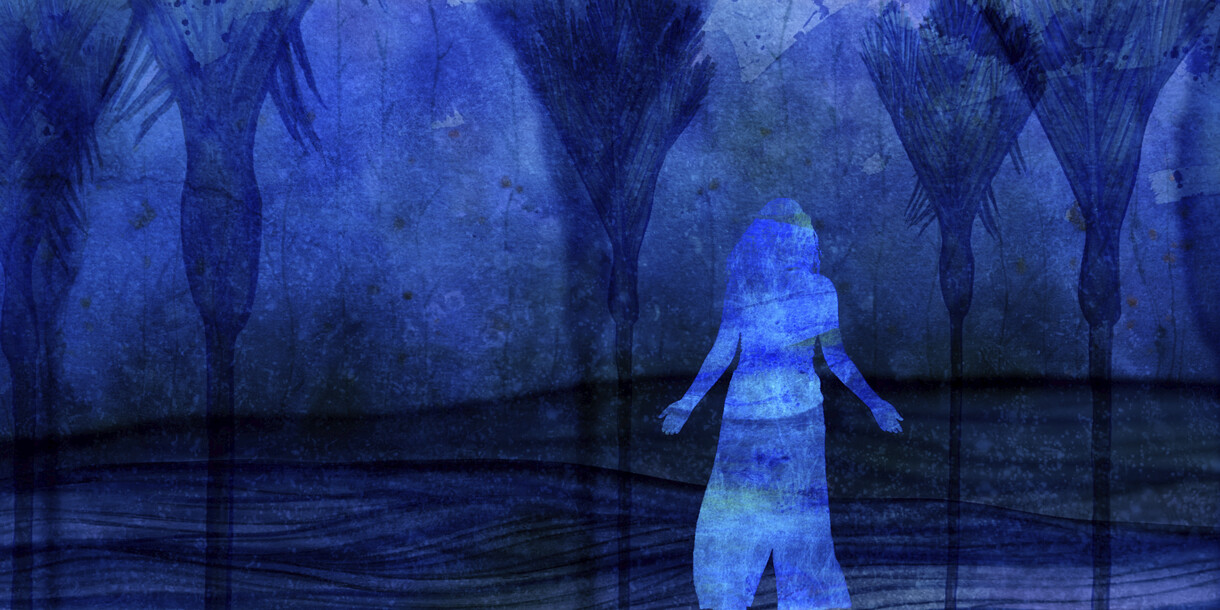

Ross Hemera Ka moe te whaea i te wai 2024. Aluminium, wood, ink, 2-channel video. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, 2024

Pouarataki curator Māori Chloe Cull talks with artist and designer Ross Hemera (Waitaha, Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe) about his life and work.

Chloe Cull: Mōrena Matua. Nau mai ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Tēnā koe i tō taenga mai i tēnei ata mō tēnei kōrerorero. Ko te pātai tuatahi: ko wai koe? Nō hea koe? Can you talk a little bit about yourself?

Ross Hemera: Kia ora, Chloe. Ngā mihi. Kua tae mai au i tēnei whare, Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Tēnā koe. I guess the important thing when I’m asked a question about who I am, what I am and what I do, is to say that I have developed a very strong affiliation to my iwi, Ngāi Tahu. Once upon a time I hadn’t, but I think that through the passage of time and through my involvement in toi Māori, I have begun to strengthen my sense of identity.

When my dad took us children down the Waitaki River and showed us examples of rock drawings, that was the very first time that I made the connection between the mahi toi with my identity as Māori. Dad was Māori, so I always knew that from a very young age, but when I saw those drawings I thought “Okay, these were made by people that were, kind of, my ancestors.” I realised these were people who I might have related to at a point way back in time. As a kid I probably didn’t formalise it in that way – it was just a feeling that we had a connection – but later I was able to think that through.

CC: Tell me about growing up in Ōmārama.

RH: Āe. My dad was working for the Ministry of Works driving a grader – he was the best grader driver around! There was only one other, but my dad was considered to be pretty good at what he did and he had a very strong work ethic. Ōmārama was an amazing place to grow up – wide open spaces and no boundaries. Well… maybe a few boundaries that dad put up, and we’d get a clip round the ear if we did things that we weren’t meant to be doing. But there were very few boundaries in terms of where we went and what we did. We roamed the hillsides, up and down the river, everywhere. And there was no time to be home – it was always after dark.

I do remember, as a child, feeling that we were extremely well looked after and we didn’t want for anything, but of course, I never knew – we never knew what else there was. I think back now to what our lifestyle was like, and if my grandchildren today were put in that situation, they’d be devastated! We went to bed by candlelight. There was a fireplace, a coal range and our food was mostly mutton and potatoes and a few vegetables that dad grew. That was about it. Porridge in the mornings.

CC: Good Southern way to start the day.

RH: Oh, man, it was very very wholesome, and I guess a bit basic! My brother Teri and I were always drawing pictures, you know, drawing, drawing, drawing... From preschool age I think we got used to the idea that we could draw well. Our local primary school had about fifteen kids in it, not many more than that. We were told we were good at drawing in school, so we kept on drawing. If you’re told you’re good at something, you tend to pursue it. And then dad would take us down the river fishing. He was really keen on it. He could draw too – in his day he was pretty talented – but his interest was really in Ngāi Tahu cultural practices from way down in Colac Bay where he grew up.

CC: You have whakapapa to that area?

RH: Yeah. And we also have whakapapa to the Tītī Islands – we’ve got land down there, and strong connections with a lot of the families too. I remember dad taking us down there to see his whānau. He was brought up whāngai by another Māori family and was pretty skilled at some of those cultural practices around fishing and tītī and I think a bit of growing stuff. I hear stories from people like Tiny Metzger (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Kūri/Rakiura) about my dad that I never knew because he never talked about what he did when he was a kid. He wouldn’t have thought it was important, but I do now. Had I known how to talk to him, I could have spent more time getting the information from him, but I didn’t know...

CC: It’s not easy when you’re young.

RH: I didn’t know how to ask, but I do know the kinds of things he did and I still keep those… I cherish those little memories. The way he would go about catching eels, tuna, the way he’d go about catching his fish, planting his potatoes. All the things that were obviously skills that he’d learnt a long time ago. And when he took us down the river, because he was keen on fishing, he would find this place where the rock drawings were. I don’t know how he knew, but he did, and he put us on a ledge and there they were.

Ross Hemera’s Ka moe te whaea i te wai (2024) installed as part of He Kapuka Oneone – A Handful of Soil in Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2024

CC: Was that along the Ahuriri River?

RH: Yes. We’d sit there for ages drawing them, copying them down. I relive those experiences regularly. They’re with me all the time – they don’t diminish. They’re just there and I can pull them out whenever I want to. So when I think about Ōmārama I think about how formative it was as a young person to grow up down there with all sorts of freedoms.

CC: And when you started studying and practicing as an artist, were those experiences always embedded in your practice?

RH: No. I mean when we were drawing as kids, I made the connection with rock drawings – “That’s a drawing and I’m drawing and I’m copying that drawing.” Then we’d be at primary school and all the other kids would ask, “Can you draw this for us?” And my report card from my art teacher was always very good. Looking back at that, I find it kind of interesting to see a report card from a teacher that you were so close to. They were almost like family, in a way.

I think from very early age I knew that I’d be doing something with art – we both did, Teri and I. When it was time for high school, our family had to leave Ōmārama because our parents didn’t have enough money to send us to boarding school. All the other kids from the district were farming kids and so they got sent to boarding school and came home to their families in the holidays. We couldn’t afford that so we went and lived closer to Ōamaru. At Waitaki Boys High School, the experience was repeated; from third form and right through we were always seen as good at art and used to get the art prizes. The year we did our school certificate I think I got a ninety-seven and Teri got a ninety-six so we had our photo in the paper. Our art teacher was Colin Wheeler. He did a number of things, including a bit of graphic design, but his love was painting the high country. And he could draw. That guy could illustrate. He was very, very good. Of course, I think that as kids that’s what we did too; we illustrated and, in the bigger, broader picture of things, what our ancestors did was also illustrate. Our illustrations were of the high country; the European idea of what life looked like. We didn’t illustrate Māori life until after art school.

Even from a very young age, that passion was always there to keep drawing and painting. Art school was a real eye-opener, but actually the art world beyond that is so much bigger.

CC: And at the time you think art school is such a big deal, but actually…

RH: So small. Such a small, small place. I had just left home and was doing a whole lot of other things as a young person and kind of learning about the world and what I could do in it – how far I could push boundaries and stuff like that. There were a number of people who were important to me during my art school experience. One lecturer who was really pivotal – probably more so than I actually realised at the time, was Malcolm Murchie. His wife Elizabeth [Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāi Tahu] was from Arowhenua and she ended up being, for a period of time, chairperson of the Māori Women’s Welfare League. Malcolm had a good grasp of the reo. He recognised and acknowledged that Teri and I were Ngāi Tahu boys. I knew that I was Ngāi Tahu, but I was always a Māori boy rather than a Ngāi Tahu boy and I think that was a bit of a shift in my thinking. Elizabeth and Malcolm used to invite us round to their home and feed us lovely kai. They were kind of like uncle and auntie during our art school days and it was Malcolm that made me aware of how important my Ngāi Tahu background was. It wasn’t something that I was expressing because there wasn’t anywhere to do that but as soon as I started talking about who I was as an artist then yes, I could say, “I’m Ngāi Tahu”, rather than just Māori.

So, straight after art school, my brother went to Christchurch Teachers’ College, and I went to Auckland.

CC: Teachers’ college in Auckland?

RH: Āe, teachers’ college. You might ask, “Why – what was that all about, Ross?” Well, I met this girl, you see, and of course she lived in the North Island. I wanted to go to secondary teachers’ college, so the closest one was in Auckland. We were this really shy, young Ngāi Tahu boy and his girlfriend. We got married and went to Auckland and I went to training college, and it was then that the world of Māori art opened up. Two people, Georgina Kirby [Ngāti Kahungunu] – have you heard of Georgina Kirby?

CC: Āe.

RH: And Arnold [Manaaki] Wilson [Ngāi Tūhoe, Te Arawa]. Well Arnold and Georgina already knew I had arrived in Auckland before I even knew who they were! There was a grapevine that went between Malcolm and Elizabeth and those ones up north. Georgina took me under her wing, as did Arnold. It was around that time that the first Ngā Puna Waihanga [New Zealand Māori Artists and Writers Association] conferences were being held, and Teri and I went to the second one, which I think was in Rotoiti. Amazing. I was just blown away by the whole thing, all these Māori people, wow, and they’ve all come together and they’re all good at art. It was just amazing.

Of course, we were still doing our European art. We weren’t making Māori art at that time. But that move to the North Island opened the window on a huge world of Māori art and it wasn’t long after that I recognised what a lot of the Māori artists were doing. Para [Paratene Matchitt] had a big influence on how I thought about art, so did a lot of those guys. They were still illustrating, but the subject and content was different. They were telling stories about the Māori world and I saw that straight away. I thought, “This is amazing. This is more about me now. This is about who I am.”

CC: What an opportunity to be surrounded by all of those senior artists.

RH: It was amazing. I got myself involved – heavily involved. Ngā Puna Waihanga was a groundswell of amazing energy in the arts, in Māori arts. It was about Māori art and out of that came iwi art. Soon there were branches up and down the country. After I’d been teaching for a few years I ended up in Rotorua, leading the programme at Waiariki Polytechnic, and there was a Ngā Puna Waihanga branch there. There was one branch down here [Ōtautahi] too and it was led by Trish, Patricia Wallace [Ngāti Porou]. It must’ve been a few years later again, but Cath Brown [Ngāi Tahu] was also involved and had always been in contact and wanted to know how we were going and stuff like that. I formed quite a nice relationship with Cath over that period of time from the 1980s through to about the 2000s.

So, there’s all sorts of things going on but by the end of the 1990s, maybe 2000, Ngā Puna Waihanga had kind of run its course and iwi art became much more important. There was a whole generation, probably two generations, of people who were coming along and we had actually created some of those generations through the programmes that we ran at the different polytechnics around the country. There was a huge upsurge. It was massive when I think about it.

CC: And do you think it was once the strength of Māori arts was established, through Ngā Puna Waihanga, that there was then room for identifying as a Ngāi Tahu artist (or Ngāti Porou or Kahungunu etc.)?

RH: I think people were probably doing that right at the very beginning, but the need to connect with other Māori artists was probably stronger and so you met under that banner of Māori art rather than Ngāi Tahu or something other. Then there were a number of exhibitions culminating in a fairly big show at the museum in Wellington.

CC: Kohia ko Taikaka Anake.

RH: Anake, yes.

CC: And there were iwi spaces in that exhibition?

RH: They weren’t iwi spaces per se, they were [Ngā Puna Waihanga] branch spaces.

CC: Right. Thinking about your work now, what is it about rock art that continues to inspire your practice?

RH: It was probably the case that even in my early days, some of the very early pieces of work that I did were related to the rock drawings. I made that connection with the rock drawings because of my Ngāi Tahu identity and so even though we were working under a ‘Māori artist’ banner at that time, I think everyone was probably referencing their own whakapapa in a way.

My recognition of my whakapapa in my art was quite early in that move from South to North and it took making that move to become aware of that. When you come to another territory or rohe, you’ve got to know what your whakapapa is if you’re going there. It’s tikanga within the Māori world. And you had to pick it up, no one told you.

CC: No, you just had to look and see what everyone else was doing. Do you see rock art as being part of the whakapapa of Ngāi Tahu arts and part of your whakapapa as an artist?

RH: Absolutely. I think we’re fortunate as Ngāi Tahu that rock art still exists. It’s one of the earliest art forms that we have in Aotearoa – it’s tapu and taonga at the same time. Each day it becomes more significant because of what it is and because of our recognition of how important that heritage is, that whakapapa is. It’s the way that we as Ngāi Tahu connect with the land because that’s what our ancestors did. They forged powerful connections with the land for us, and they did that by doing those drawings. It’s more than what you can actually say in words.

CC: You’re here this week to install your new work, Ka moe te whaea i te wai which is a new commission and a new acquisition for the Gallery. To finish, would you mind talking a little bit about that work and the kaupapa behind it?

RH: That work is about how our Ngāi Tahu narratives talk about whenua, and how the land emerged from the sea. It’s about illustrating that narrative. When our ancestors applied kōkōwai or ngārehu to stone, they recognised it would be there for a long time. That is really significant. That’s what I think about when I’m undertaking a new work: “What are the motifs I’m going to put on that?” I use imagery that talks about who I am and what I am, and that imagery comes from a long history of image making, a long whakapapa of imagery from way back. It’s the same as where language comes from, you know, oral language. When I make a work, I’m thinking about the processes of my tīpuna.

When you make marks, they can tell so much and the mark itself becomes a means of communication. It becomes a means of recognition. A simple mark on a wall has the power to influence how you think about and how you see the world. Our tīpuna created so many different images and we refer to those and pull them out and use them today in our language of mahi toi.

Now, that reservoir, that library of images is pretty big but it stopped being added to a couple of hundred years ago when ana whakairo was no longer practised. That imagery is our Ngāi Tahu visual reservoir. I think let’s not end it there. Let’s move some of that imagery into today.

Over the last twenty years or more I have been developing interpretations of those images. The reason I’m doing that and will continue to do that for a long time, I imagine, is because there’s so much to be done and so much to be discovered. Although I’ve been analysing these marks for thirty-odd years, I still don’t understand what they’re about, there is so much learning to be done. I have to interpret them to get closer to what they’re all about and that interpretation is an absolute in-depth study of the forms. Then I can pull some of that out and create new ones.

CC: Tēnā koe Matua i tō kōrero i tēnei ata. Thank you, it’s been a pleasure.

This is an edited version of a conversation between Ross Hemera and Chloe Cull that was recorded in August 2024.