Whenua is a Portal

Earth Pigments and Māori Practitioners in Contemporary Art

Te Ara Minhinnick He taonga te ware 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Artspace Aotearoa

Manawa mai tēnei i Ahuone mai

Manawa mai tēnei i whenuatia

Manawa mai tēnei he kapunga oneone

Tēnei te mauri

o Papatūānuku,

o Tūparimaunga,

o Parawhenuamea,

o Ukurangi

E whakaata mai nei e

Kōkiri!

Sharp volcanic reds, grey river clays tinted with soft blues, yellows like mustard, bright flashes of orange and gemstone purples. Before you spend time searching the environment around you, it’s hard to imagine a full spectrum of colour coming from earth pigments, from whenua. We are more used to shiny bottles of coloured acrylic or bright tubes of foreign oil paints – of unknown origin or maker. But for the majority of human history earth pigments have been a primary resource for art making, and in some pockets of humanity, like te ao Māori, the use of earth pigments remains a constant resource of creativity. A highly localised medium, whenua is political, it is cultural and it is sacred.

In Aotearoa, whenua has been used by Māori for many purposes. Whenua is a dye for clothing and a stain for taonga. The bright red adorning a wharenui would have historically been kōkōwai, a rich iron- oxide pigment. The application of whenua could be ceremonial, sacred, but also domestic; there’s a painted depiction that I love of a young person from Ngāti Awa adorned with kōkōwai on the cheeks. Sometimes it served a practical purpose too, like layers of pukepoto or clay covering the body to protect from insect bites. The legacy of whenua as adornment was on display at this year’s Te Matatini competition in the smoky grey silt on the legs of the Mātangirau kapa from Wairoa – silt gathered that very week in the wake of Cyclone Gabrielle which had destroyed their hometown.

The use of whenua in contemporary art by Māori artists will always speak to the historical legacy of the resource. I think of Areta Wilkinson and Ross Hemera, both influential Ngāi Tahu artists and members of the Paemanu collective, who have been using whenua in their creative art practice for a long time. Hemera has spoken of his childhood visits to sites of Ngāi Tahu rock art, and being prompted by his father to draw them with paper and crayon. Some of those sites are no longer accessible, but are reflected in his artworks. For Hemera, the kupu for kōkōwai is maukoroa.

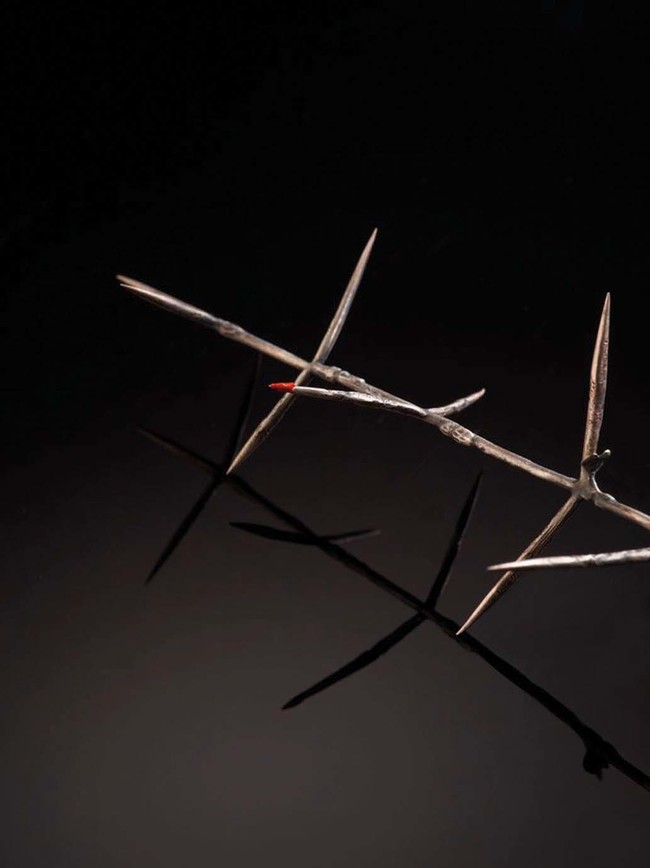

Areta Wilkinson Tūmatakuru wears me 2008. Sterling silver, kōkōwai. Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased 2011

Wilkinson’s work Tūmatakuru wears me is a personal joy for me – a sprig of the thorny bush plant tūmatakuru/matagouri cast in sterling silver with a single prick point of kōkōwai as blood. Wilkinson’s use of whenua is loaded with meaning. It calls on whakapapa and the practice of our tīpuna. It might also speak to colonisation and to a re- indigenising by reconnection to whenua. As earth that literally comes from a specific place, it speaks to origins and the places that we come from too.

There is also a wider global conversation to be had about the decolonisation and democratisation of the art world. Whenua speaks to a kind of art-making that is accessible, and that accessibility only makes the resource more special. There is little more important to us as Māori than our whenua, when we have lost so much of it through colonisation. As such, whenua is and must be treated with care. Even a smear of earth left in a mortar or on the pestle will be saved.

It feels important to acknowledge that the label ‘contemporary art’ is loaded too. It often comes with the assumption that art made now must be the kind of thing you can view in a gallery. But that definition is limited and exclusionary from a Māori point of view. For a start, it excludes the creatives who might be called ‘traditional Māori artists’ – a label that honours legacy but dismisses the innovation, relevance and influence of their own creative practices. Of these artists there are too many to count, but I acknowledge some of my favourites: Veranoa Hetet, Isaac Te Awa, Hamuera Manihera.

Sarah Hudson Return (still) 2022. HD Video, colour, sound; 10min audio composition: Te Kahureremoa Taumata; Cinematography: Rachel Anson. Courtesy of the artist

The author wears a corner of aute bark painted with whenua pigments by Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss. Handsewn on to garments by Cora-Allan as part of a showcase at Te Papa during Matariki 2022.

There is a younger generation of contemporary artists influenced by senior artists such as Hemera and Wilkinson, and they are overwhelmingly wāhine. Papatūānuku is aligned with ira wāhine, and thus the link with practitioners seems apt. I think first of my tuakana in Kauae Raro, Sarah Hudson, whose work with whenua is influential to many Māori attempting to find and ground in a language of creativity. Her leadership within Kauae Raro is also significant, leading discussions about the democratisation and political practice of whenua, the connection and the joy of it. Exhibited at Blue Oyster Gallery in Ōtepoti last year, Hudson’s re:place centred on the Tūhoe concept of matemateāone, and whenua was the primary material. I was drawn in particular to the video works featuring dyed fabrics washing clouds of whenua into the moana, and the earth orbs polished to a smooth shine.

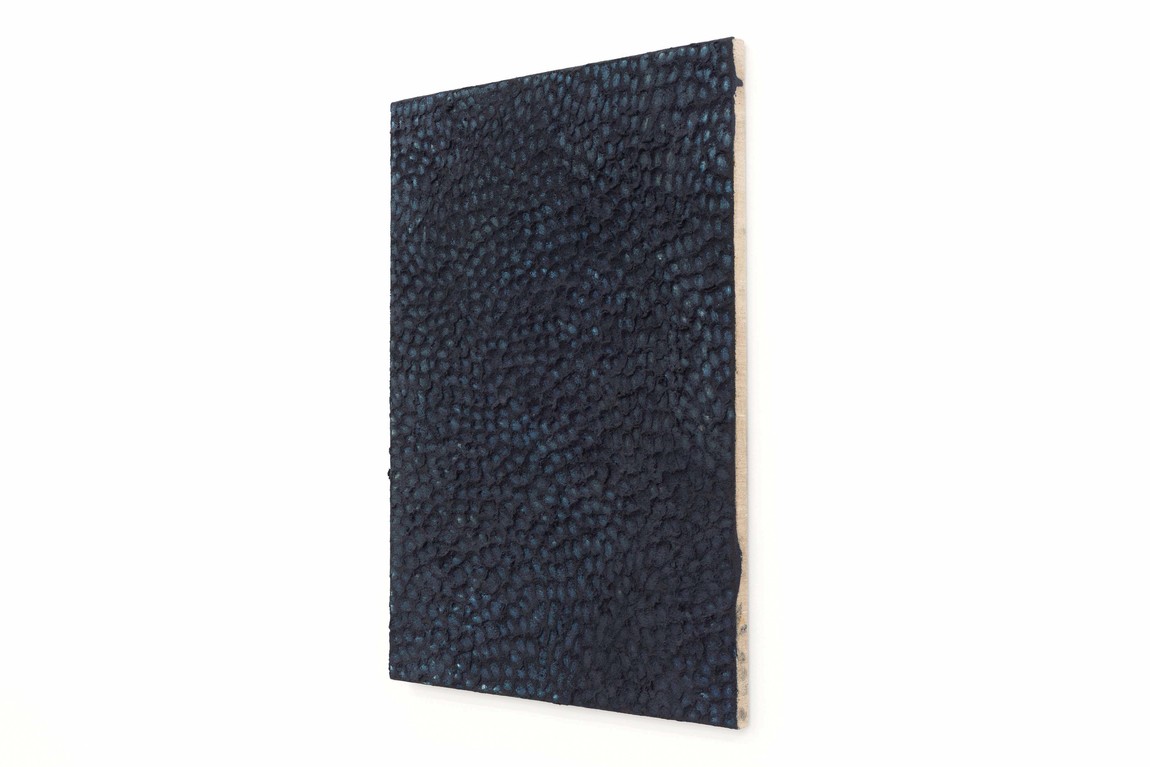

Raukura Turei uses earth pigments like the delicate duck-egg blue aumoana from her whenua to create artworks that are magnetic in their daubed patterning. I love the range of colours, the skill used to apply whenua at that scale, and the clear presence of the maker’s hand, reminiscent of the tuhi māreikura practice of our tīpuna.

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss, who is Māori and Niuean, has primarily worked with whenua within a Niuean context and is a significant figure in the revival of hiapo. During the Matariki celebrations at Te Papa in 2022, she spent days sewing small triangles of hiapo painted with kōkōwai and ashy black ink onto the clothing of visitors to the museum. The triangles were inspired by a kōrero with Tūhoe practitioner Chaz Doherty, who talked about how hiapo (or the Aotearoa equivalent, aute) was used by Māori.

Raukura Turei Te au a Hine-Moana 2022. Oil, pigment and onepū (black sand) on linen, various sizes. Photo: Cheska Brown

Among a new generation of practitioners, the sounds of beating fibres and sloshing buckets of silt ring out. Nikau Hindin is well-known for her use of whenua and aute. Her work often incorporates precise astronomical calculations that echo the navigational abilities of our tīpuna. That skill and dialogue is on display in works such as Te Uranga, which shows the rising and setting of the sun at the autumn equinox.

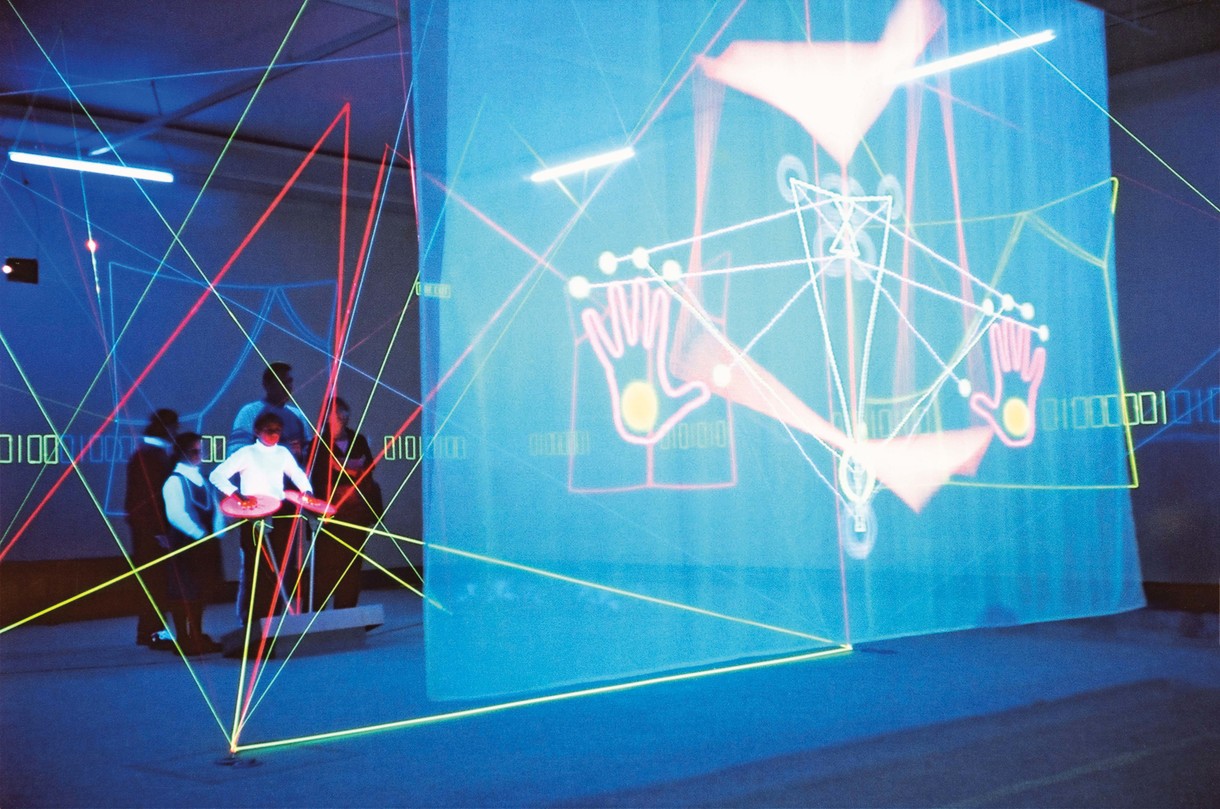

Another young contemporary maker who I am excited by is Te Ara Minhinnick. Minhinnick comes from a place called Waiuku, which could be translated as water filled with clay. It is so appropriate then that uku is central to her work, which often consists of blocks of clay and whenua, on smaller and larger scales. Her work He taonga te ware comprised large blocks in uku, onepū, and kerewhenua earth, and I am sad not to have seen it in person at Artspace Aotearoa.

So what is the significance of working with whenua and earth pigments in our contemporary creative context? Why do artists do it and what does it evoke? What are the implications of whenua use? As with much within te ao Māori, the use of whenua is a praxis that expands conversations out of the sterile art world and grounds them in the real, lived world. Whenua is a political medium that evokes strong emotions in those of us who know how precious a handful of dirt is. There is a whakataukī that we love in the whenua world:

Tukua mai he kapunga oneone ki ahau, hei tangi māku.

Give me a handful of soil so that I may weep over it.

Whenua is such a significant art-making material because it can take us back to the waters of Waiuku, or to the rivers where we come from. It is a portal to the future – I think of Tessa Russel’s work melding whenua with a kind of natural bio plastic – and it is a portal to activate the past, as in Kezia Whakamoe’s ceremonial use of earth in her exhibition Aukati.

Whenua can activate a simple joy, like children making mud pies on a hot day. It is a portal because it can evoke a sense of closeness and intimacy with tīpuna, or like seeds planted in soil, it might evoke futures to come. Tradition and futurisms look different in the context of an indigenous culture, outside the tireless reflex to innovate purely for the sake of it. To work with whenua feels like that. Past and present and future rolled in to one. In a way that is not contrived, is not forced, but often effortless. More than anything else, with whenua it is the context that matters most.

We have not provided English translations for the te reo Māori used throughout this text. If you would like translations to support your understanding, we suggest the following resources:

H. W. Williams, A Dictionary of the Māori Language. 7th ed (1971)

The karakia shared at the opening of this text was composed by Te Kahureremoa Taumata and Khali Philips-Barbara for the purpose of gathering and working with whenua.

Tessa Russell He taonga te wai (detail) 2021. Bioplastic created from bark cellulose, water, almond oil and whenua pigments