String Games

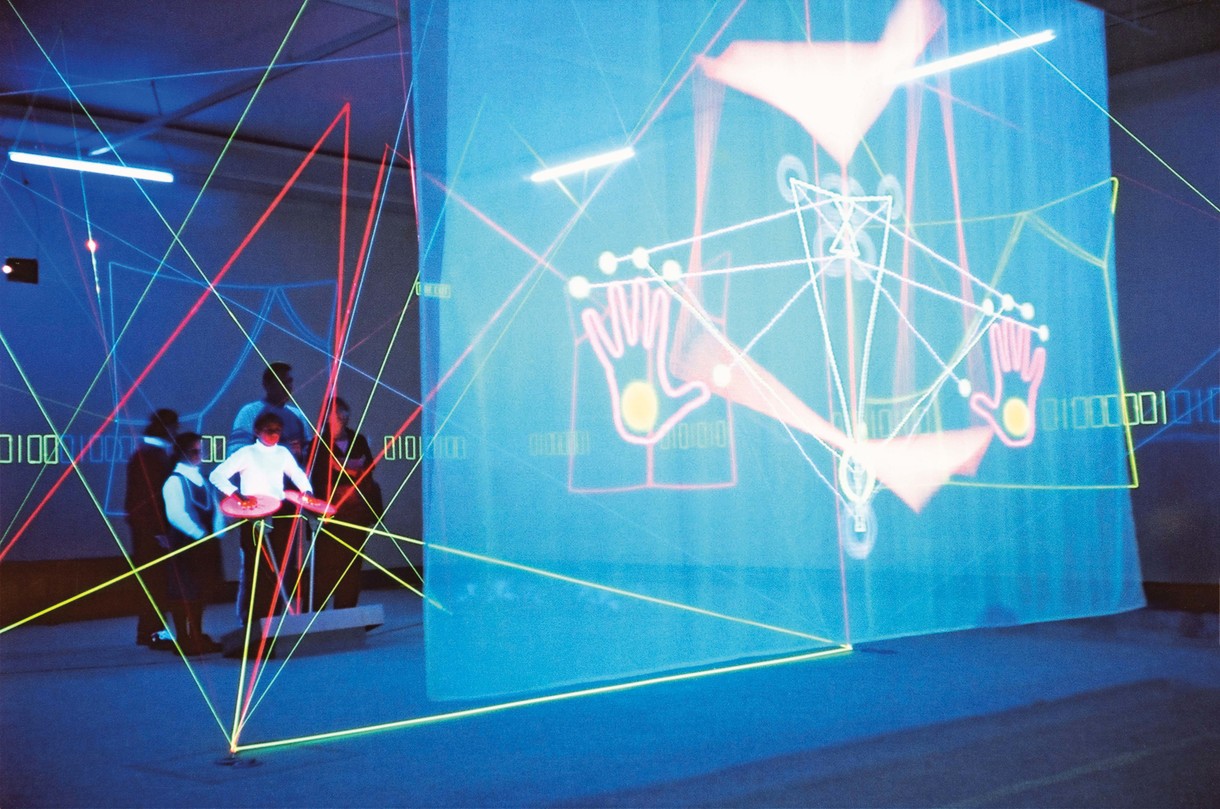

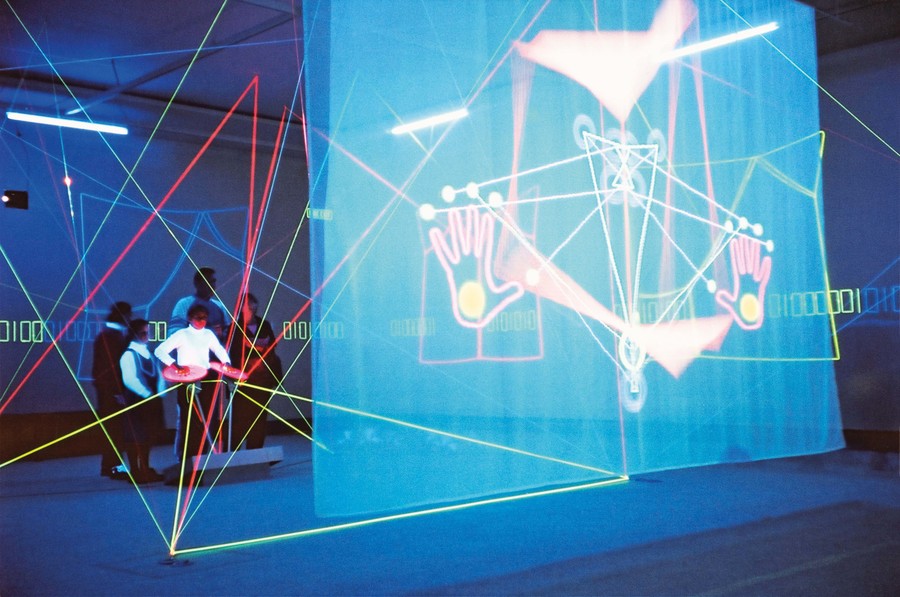

Maureen Lander and John Fairclough Digital String Games II (installation view) 2000. Interactive digital installation. Courtesy of Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

“If you think about it, digital, it’s something you play with string, your fingers and a language of computers, strings of binary code. The interplay of old and new. ”1

The first instruments we used to count were digits – fingers (and toes). From the Latin, digitus, the word was subsequently borrowed to name the numerals one to nine. It is also the root of the term ‘digital’ in relation to machine technologies, which operate along unravelling strings of binary code. Artist Maureen Lander’s 1998 installation String Games follows this thread, proposing that the digital can be grasped and rendered like string looped around fingers; correlating the material forms of whai (Māori string games) and digital technologies.

Maureen Lander is an artist and academic of Ngāpuhi, Te Hikutu and Pākehā descent who has been exhibiting, teaching and mentoring in fine art and Māori material culture for the last forty years. Her practice intertwines with te whare pora (the house of weaving), following its materials and processes as channels to tap into the metaphysical ideas that drive her work, as well as the circumstances her work sits within.

String Games was commissioned for the opening of Te Papa Tongarewa on the Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington waterfront. Immersive and site-specific, it is dominated by a giant, UV-lit installation composed of fluorescent marine-braided rope and based on a customary string game called a whare kēhua, or house of spirits. At the centre of this construction is a floating neon-green box. Smaller configurations on the surrounding walls and floor map out various other string patterns practised in Aotearoa, creating the optical illusion that the space extends into a weightless void around them. After its presentation at Te Papa, String Games had more iterations, which were retitled Digital String Games I, II and III.2 Made in collaboration with the Pākehā artist John Fairclough, they introduced new interactive elements that engaged fingers and thumbs, using a game pad to project changing patterns within the installations.

String Games expanded the scope of Lander’s site-specific practice. At this time, she often responded to a site through her choice of materials, considering the meanings they might lend to the work and its broader contexts.3 The new Te Papa Tongarewa was built to reflect recent government policy, which had begun to finally acknowledge the Treaty of Waitangi as the founding document of this nation state. This new museology would overturn old models of representation, packing away “the crusty old museum exhibitions of yore” and identify new treasures and taonga which could tell the nation’s stories.4 These objects would be presented within “dynamic”, “interactive” and “challenging” exhibition frameworks that “interpret[ed] our world – and what we’re guardians of – back to ourselves”.5 Collection items were unearthed in the hundreds as the key medium of the museum’s new mandate, and artists – including Lander, Lisa Reihana and Greg Semu – were invited to respond to the collection for the exhibition Facing IT. Lander’s previous work had for the most part formed connections to site through the incorporation of locally sourced or repurposed natural materials, but String Games doesn’t include any of these kinds of materials. I would argue that instead it forms its connections to site through Te Papa’s constitutional material: the items in its collection.

Maureen Lander String Games 1998. Rope, nylon fishing wire, neon painted string, cardboard, paper, linen, glue, laser discs, CDs, photographic prints, white and ultra-violet light. Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, commissioned 1998

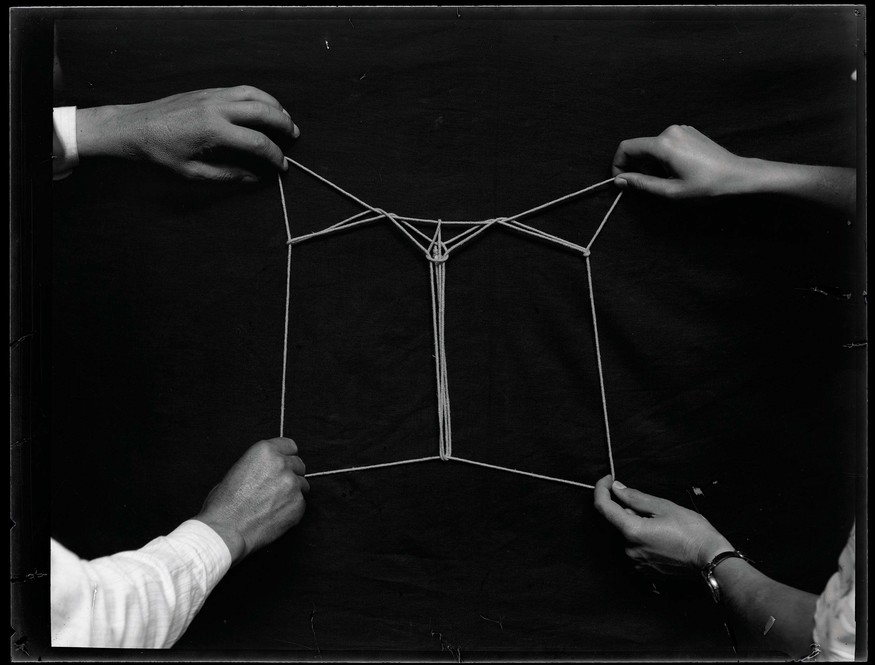

The work’s first ‘material’ is a series of photographs of whai made by Pākehā ethnographic photographer James McDonald between 1912 and 1926 among communities in Rotorua; Koritini, Hiruhāmara and Pipiriki on the Whanganui River; and at Whareponga, Waiomatatini, Waitangirua and Te Araroa on the East Coast.6 Whai is considered an ancient pastime among Māori, believed to have been gifted by Māui and/or patupaiarehe, but the practice also appears among societies across the world – in the United Kingdom

it’s called ‘cat’s cradle’. Muka string is looped around fingers and hands (or groups of fingers and hands) to create symbolic constructions that change with minor adjustments, often animating specific pūrākau and accompanied by waiata. An alcove in the installation is dedicated to these photographs. UV lights illuminate the hands in the photographs like the ropes in the installation. According to Lander, String Games recovers this heirloom from a conflicted history of colonial anthropology and makes that knowledge “accessible back to the people it was collected from.”7

The second ‘material’ in the work comes from the European modernist Marcel Duchamp, who is represented in Te Papa’s collection by an edition of his 1930s series Boîte en valise – a ‘travelling-suitcase museum’ that holds miniature versions of the artist’s key works. Lander had wanted to incorporate the real object within her installation, but as this was not possible the floating neon box at the centre of String Games acts as a reference – a closed container of unknowable objects. A corresponding alcove includes a photograph of Duchamp’s 1942 installation Sixteen Miles of String. This work, a canonised precursor to what we now dub ‘installation’, is a key influence in String Games.

While these two materials might seem very different, Lander’s work renders them at the intersection of multiple entangled histories. These wind together in two films which present a pair of gloved hands delicately unpacking the contents of Te Papa’s edition of Boîte en valise, pausing with each miniature work so the viewer can take it in. Different ungloved hands then begin to refill the box with McDonald’s photographs of whai, a copy of J. C. Andersen’s 1927 book Māori String Figures, and a pair of mussel shells, which are the tools used for creating muka for string. This performance is interwoven between McDonald’s archived footage from the 1920s and footage created by Lander of contemporary Māori also creating whai. They sit in green spaces, on park benches, in marae, and sing waiata. Moving back and forth in time, the films chart the survival of the practice.

James McDonald Māori String Games – Ara Pikipiki a Tawhaki 1912–26. Black and white gelatin glass negative. Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Channelling questions that Duchamp posed in his own work, but in a context where he himself represents a kind of imperialism, in layered ways these films make clear that String Games responds to its site – to the politics of looking, the machinations of the Antipodean museum, its colonial inheritances and its intentions for the future. Lander brings to light a historicised Indigenous practice and reanimates it through the legacy of an imported (or freighted) and fraught colonial art history. String Games creates a dynamic allegory that reflects the shifting complexity of cultural relations in Aotearoa New Zealand, amid a rapidly globalising world propelled by technological advancements.

By 1998, nationwide ownership of personal computers was increasing exponentially, in part out of a demand to access the computer network called ‘the Internet’. FAQ’s written by computer-engineering students for newspapers placed quotation marks around words like ‘pages’, ‘forums’ and ‘gateways’,8 anticipating confusion around their employment – the dog-eared corners, podiums, hands and bodies implied in these words were far from the actual experience of ‘cyberspace’. At the outset, the increase in PC ownership was driven by the desire for these telecommunications capacities, but even in its early stages discussions alluded to the possibilities of virtual interaction, which “allow[ed] people to wander around a simulated world, interacting as if they were physically in the same place.”9 While information technology may have only repackaged the ways humans had always communicated with one another, its space- collapsing immediacy radically changed how information was received and thus understood in relation to the environment.

According to Lander, String Games would “pick up on the word ‘digit’ which in the older sense is simply the use of ‘fingers’” and find likenesses across the forms and processes of whai and then-new digital technologies: “[creating] a kind of ‘whakapapa’ for the relationship of technology to this particular art form [string games] – manual, photographic, film, video, sound, computer, www.”10 We might also insert the 20,000-year technology of string into this continuum, as well as the textiles, looms and Jacquard machines it later sustained, which crucially informed computer technologies as we know them today – as philosopher Sadie Plant has said, “weaving wends its way through even the media which supplant it.”11 At the time, Plant probably didn’t realise how true her analogy was: the digital interface, wherein “data and code function primarily as a single stream or thread”, is now understood to be literally woven or knitted like the pattern for a weave on an eight-thread warp.12

Maureen Lander and John Fairclough Digital String Games II (installation view) 2000. Interactive digital installation. Courtesy of Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

While digitality is commonly associated with immaterial modes of communication, connection and consciousness, along with the utopian possibilities that come with this, String Games proposes an alternate route through these perceptions. In order to engage with String Games deeper – on a fibrous, mineral level – we need to dwell on the connotations of its materiality and the correlations held within this materiality. Glowing as if they are electrified, the strings in String Games echo the strings that create whai – harakeke, muka – and the strings that create digital technologies – copper wire, electrons. They are one and the same, represented simultaneously.

Importantly, both systems are identified as mediums: symbolic constructions that translate stories, or the conduits for digital code that translate text or images. They are both distinctly material, inciting reflections on how digital technologies mediate our relations to the material world. Inherently, String Games also stirs an awareness of hands and fingers – digits looped around string that weave and interlace to create discrete symbols. While numerical digits propel the digital technologies we interact with on a daily basis, our fingers have always been the point where we meet them, from the clicking of vacuum tubes in the first warehouse-sized computers, to the tapping of keys on a personal keyboard and the swiping of a palm- sized screen.

Our body is thus inherently involved in String Games, too, not only through its allusion to fingers, but also in the way it blurs the boundaries between our corporeal limits and an expanding digital universe. Since the rise of digital technologies, discourse around ‘the body’ has only intensified – responding to the loaded promise that we can leave behind our physical bodies through cyberspace. While some have signalled the potential of a streamlined, multipurpose ‘pan-cultural’ language, String Games defines digitality at the scale of our fingers, between plasma, glass and thumbs, which weaves through individual and collective bodies and the cultural and historical frameworks that bind them. String Games recalls a material world mediated for sensuous bodies by digital technologies.

Multiple material ontologies thus coagulate within String Games, especially when you consider that the Western-defined ‘new materialism’ I am partially led by here has historically omitted any acknowledgement of the Indigenous viewpoints that heralded it.13 This unsettled, agential nature is inherent to how we might understand String Games. As Lander spoke of the work in 2000, she was interested in exploring “the tensions that occur at the interface between the two cultures,”14 represented across whai and digital systems, and framed by globalism, dial-up internet and Y2K. String Games is thus deeply embedded in and formed out of this place, offering a view of space and time that is threaded through local paradoxes of identity, power, place and space.

Whai and digital systems represent the transformation of the raw mineral world into tools of social, cultural and technological value. At the tips of human fingers, they are capable of becoming something other than themselves, and perpetuate their own networks of communication and innovation. String Games defines the digital as something held, shaped, applied and exchanged but also material, bodily, earthly. In the shimmering, slippery present, we face a paradox propelled by digital technologies, where surging screen times and a looming Metaverse sees us falling increasingly out of sync with our living, breathing, physical environment. The clairvoyant intuition of String Games illuminates relations to the digital that are bound to materials and touch. Despite being over twenty years old, it anticipates our contemporary moment.