Pecking Order

A Conversation With Judy Darragh

Judy Darragh Bread Slippers 2022. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist

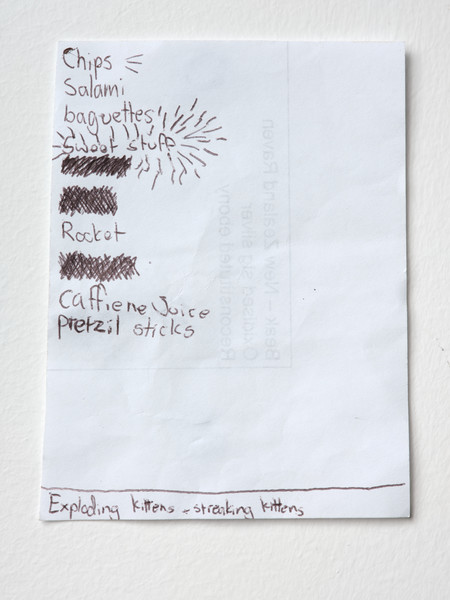

Felicity Milburn: Judy, it’s great to be working with you again, this time on a work for the entry wall leading into our new collection rehang, Perilous. It’s made up of a frieze of photographic panels combining images of handwritten lists and pieces of bread that have been partially eaten away by birds, and you’ve called it Pecking Order. Can you tell us a little about how it came about?

Judy Darragh: Thanks, it’s great to have this new work included in Perilous, it was already in existence and fitted well with ideas in the show.

Life over lockdown became reduced – we were at home, everything was shut down and it became a surreal and shared experience for us all. While out walking I observed the flourishing of bird life, and I had time to hear and feed them in the back garden every day. Feeding the birds was very satisfying.

“When I have my breakfast I cut off a slice of bread for myself and one for the birds. We are all in it together.”

Bill Sutton, 1992

Judy Darragh Pecking Order (detail) 2022. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Pecking order is a behaviour seen in hens, where one hen strives for status and hierarchy over the others. The pandemic showed how vulnerable humans are, there was no knowing who would get ill… We could get pecked off at any time!

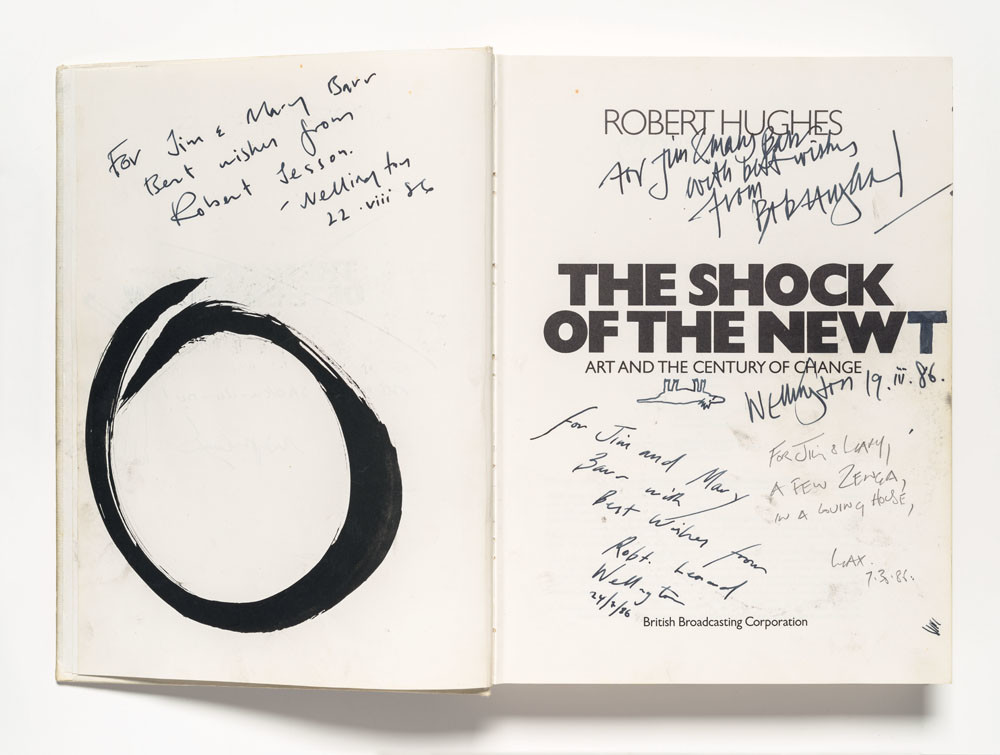

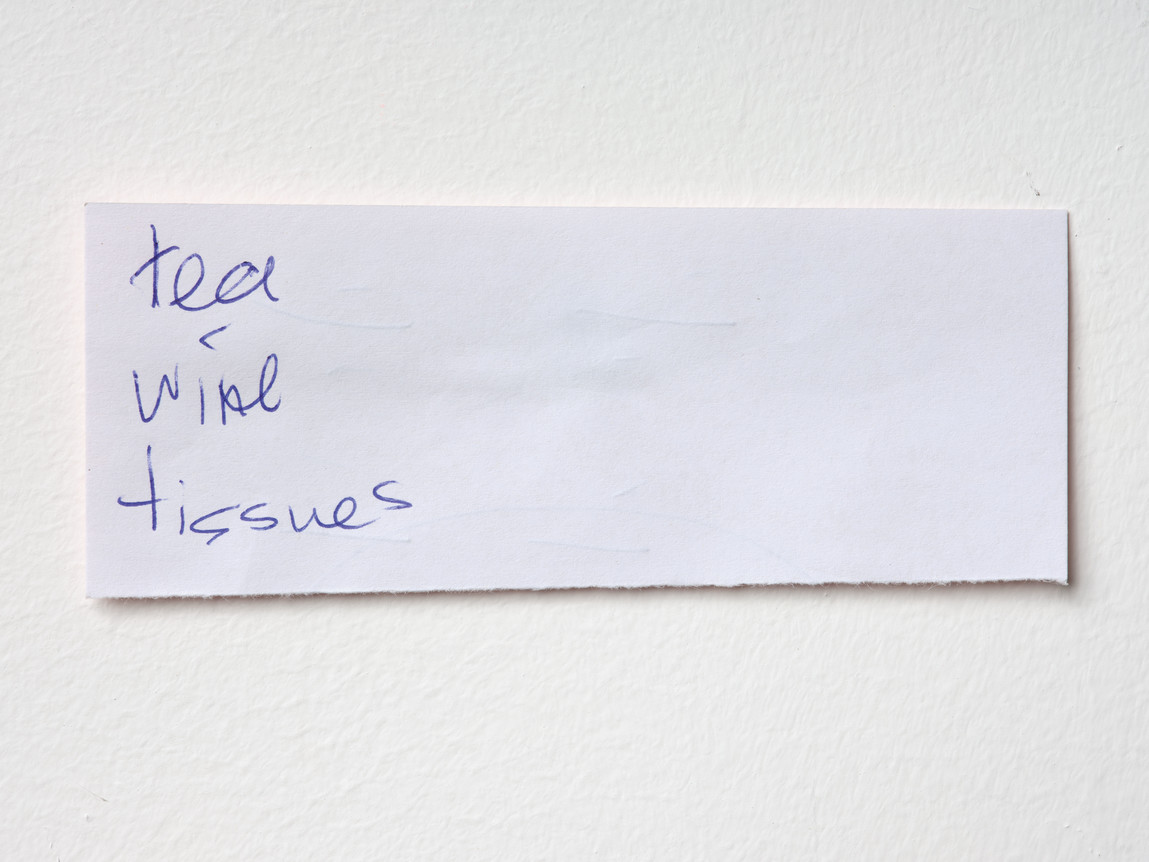

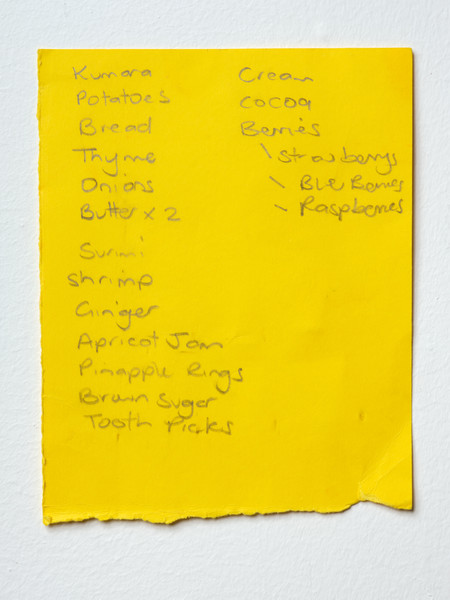

The lists are reminders discarded by people out shopping: the supermarket was one of the only places open. As we queued up outside, orderly and patient, I thought of this action as one giant relational artwork, a worldwide performance of keeping two metres away from each other.

FM: Did the lockdowns affect or change the way you work?

JD: Lockdowns weren’t great for making work for me, there was too much underlying anxiety floating around as the world plunged into the pandemic. My material supply chains weren’t available and online suppliers didn’t really work. The supermarket became my default art material supplier.

Some people found it a very creative time, but I found it hard to extract myself from the world news updates, so I walked a lot and tried to read. I thought a lot about the impacts on our creative community and individual artists. The financial support from the government was a life saver.

FM: The lists are fascinating; they’re such a mixture of wants and needs and convey something very human about the spirit of that time. Some are shopping lists, some ‘to-dos’ – others something else entirely! I particularly like the one that just says ‘tea wine tissues’. Were there any you were especially surprised by, or charmed by? Any you found, but didn’t include?

JD: Yes, my favourite is ‘tea wine tissues’ too. I also like the ‘exploding kittens’ and ‘rubbish Glad’. I picked up the discarded lists from around the trolley areas – I had to be quick as they were usually cleaned away. Written on scrappy pieces of paper and card, they are documentary evidence of what was being cooked and eaten. I selected the lists that had some humour, and those with crossing out marks that resembled drawings.

Judy Darragh Pecking Order (detail) 2022. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Judy Darragh Pecking Order (detail) 2022. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sam Hartnett

FM: This work uses found material in the most literal sense. Do you like giving up control/agency?

JD: My practice is based on the found object… the surrealists used this element of chance and I like the moment of ‘the thing’ finding you. Art and artmaking need to be surprising – it’s joyous when you recognise some ‘unexplainable sense’ that has come from playing with ideas. I trust the instincts involved in this process.

FM: Even though you’ve found the lists, and – for the crusts – outsourced some of the making to the birds, you’ve still made a lot of decisions affecting the result – when you removed the bread from the birds, which pieces/lists you selected, the scale of the images and the colour fields behind them. What guided those choices? Was there a lot of experimentation involved?

JD: It started when the birds made me some crusty slippers. I then experimented with different breads – they went for the soft breads first, seeded bread lasted longer. The insides were eaten first, leaving various crust shapes. I could control the timing and bread texture; it was like a game. The backyard became my studio.

The fluorescent backgrounds take the crusts out of the everyday, the scaling up of the lists shifts them into non-human form, and the written text becomes more graphic. The seeds and grain are gigantic, resembling rocky landscapes with caves and caverns.

Bread was like a call to calm as everyone was baking and hoarding flour. Our daily bread became a comfort. I roamed the supermarket isles looking for a range of grains and softness; I was excited by bread, there are so many varieties, buns, grains, gluten, textures and colour. Tortillas worked well too, as the birds pecked from around the edges in a circular motion leaving their delicate beak marks.

Judy Darragh Pecking Order (detail) 2022. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Judy Darragh Pecking Order (detail) 2022. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Sam Hartnett

FM: Our exhibition Perilous is about what can happen when we widen our gaze beyond conventional art narratives. You’ve long been engaged with challenging hierarchies and ideas about what art should/could be. Was that a conscious part of your thinking when making this work, or does it just come naturally by now?

JD: I came to artmaking from a design school perspective not fine art, which has given me freedoms. Teaching has given me the confidence to challenge what art actually is, as I try to encourage students to take risks. I embrace risk – you either succeed or you fail, and we learn more from failing. I think this is embedded in my practice now, so I don’t overthink it any more. I’m interested in the collective and advocacy; artists can be romanticised as the lone individual, but this doesn’t serve the community. We need to support each other. Being involved in artist-run initiatives has taught me the strength there is in numbers.

FM: The title of the larger show (Perilous) relates to the complexity of attempting to rebalance some of the traditional biases that have applied to art, and also acknowledges that many of the artists involved are making work that involves risk – either because it’s very personal, or dealing with contentious issues, or saying things in a new way. What part does bravery play in your practice?

JD: I was lucky to be in the slipstream of feminism, I saw brave women a generation ahead of me calling out the patriarchy. I was also at the tail end of punk and loved the freedom in challenging the establishment, which informed me politically and personally. Art should push the edges, challenge our thinking and present new ways of looking at ideas. As artists we have a ‘practice’, which suggests that if you keep working you get better, and hopefully you do get more confident and braver. Not only is the artist’s life perilous, it is also precarious financially, as there is no regular income from art making. Making art is a brave thing.

Judy Darragh spoke to Felicity Milburn in June 2022.