Impasse after impasse

Iris Gate, 1999

Barbara Tuck Iris Gate 1999. Oil and encaustic on canvas, six panels. Courtesy the artist and Anna Miles Gallery

"Reinventions can be local, low-key, small scale and subtle in their specific effects."

Allan Smith, 1995 1

Among the selection of paintings that make up Delirium Crossing, Barbara Tuck’s Iris Gate stands apart. Painted in 1999, it is the earliest work in the show. Rather than the single square paintings that follow, this is a set of six rectangular canvases. Though small in scale, they are notable for their gestural vigour and looseness, their coloured grounds looking stubbornly like painted surfaces upon which figural elements float like collage fragments. No airy atmospherics, vertiginous perspectives, intricate tracery: ‘landscape’ has yet to appear. Equally, recalling earlier works, Iris Gate departs from the shaped, multipart, laser-cut aluminium paintings for which the artist became known in the early 1990s. Against the flow of art history, it marks a return to convention, in both format and facture, a backwards move to rectilinearity and the brush.

Among the selection of paintings that make up Delirium Crossing, Barbara Tuck’s Iris Gate stands apart. Painted in 1999, it is the earliest work in the show. Rather than the single square paintings that follow, this is a set of six rectangular canvases. Though small in scale, they are notable for their gestural vigour and looseness, their coloured grounds looking stubbornly like painted surfaces upon which figural elements float like collage fragments. No airy atmospherics, vertiginous perspectives, intricate tracery: ‘landscape’ has yet to appear. Equally, recalling earlier works, Iris Gate departs from the shaped, multipart, laser-cut aluminium paintings for which the artist became known in the early 1990s. Against the flow of art history, it marks a return to convention, in both format and facture, a backwards move to rectilinearity and the brush.

Iris Gate is transitional then; a pivot. Yet transitions are seldom seamless: a gate can be a barrier as well as a way through. The paintings were made during a lengthy break from the rhythm (or treadmill) of annual exhibitions, at a juncture when Tuck dropped out of view between 1997 and 2006. Furthermore, though made in 1999, these paintings weren’t shown until 2014. Fifteen years is a long gestation. I wonder what caused this break? Did doubt produce a blockage? Did she lose her way? Struggle to escape a cul de sac? No need to ask: the painting’s title proves the impediment, or at least gives shape to the threshold on which these works are perched.

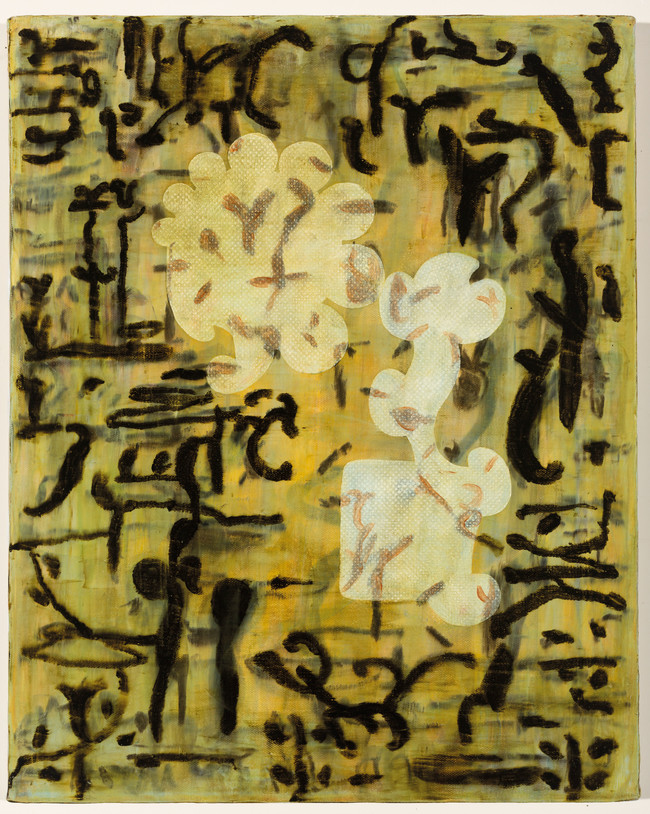

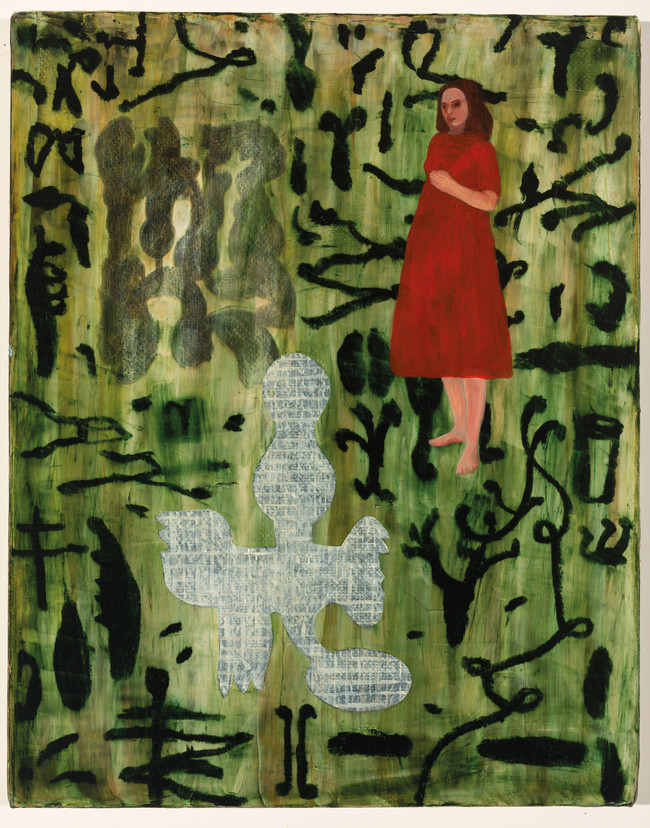

Against the forward momentum of a progressive history of art – the kind that governs the retrospective exhibition as a summative exercise in describing an artist’s ‘development’ – Iris Gate seems to reverse, elongate or even collapse time. Its hesitations are palpable. Onto a surface of brushed and coloured pigment, marks are laid evenly and at intervals. These form a calligraphy of dark or light, loosely drawn shapes that sometimes coalesce into things: a leaf here, a cylinder there, shadowy figures, a dog, a deer’s head with antlers, flames, ripples, filigree, a punctuation mark or Chinese character. These marks gesture towards language but seem to stumble or resist. They form a screen like falling rain outside a window.

Barbara Tuck Iris Gate (detail) 1999. Oil and encaustic on canvas, six panels. Courtesy the artist and Anna Miles Gallery

Floating or half-submerged, larger shapes and figures get tangled in the marks, but also hang there emphatically. Bulbous forms occur along with carefully painted figures: a naked Adam and Eve in a cloud or speech-bubble, a recumbent man and seated woman at rest, literally, on the paintwork. The art historian in me knows these to be borrowed forms, copies of absent originals: her own reworked ‘templates’; an early Flemish ‘Expulsion’; the principal figures from Nicholas Poussin’s Echo and Narcissus (c. 1627–28), a painting seen in the Louvre on the European trip she undertook alone in 1998 that was the impetus for her ‘return’ to the traditional equipment of her medium. These seem both selected and random, fragments from Tuck’s visual lexicon: half-remembered pictures, re-traced outlines of familiar shapes, the mumbled remains of looking closely. She brings these shards together as an a-temporal miscellany, ungrounded yet connected within the mesh of paint.

Tuck seems to be testing her own definition of what painting is, has been, or can be; feeling her way as much as seeing clearly. To me, her searching process tallies with its historical moment. Painters in the 1990s were working in the wake of powerful structuring narratives, beyond the avant-garde’s distrust of realism, past modernist formalism’s strictures, on the tail of postmodernism’s doubt, after painting’s 1960s’ end-games and 1980s’ returns. The medium had survived and was regrouping. There was a new pressure to find purpose beyond ironic quotation, to reinvest the sign with more than blunt materiality, the world was seeping back in to picture making.

Allan Smith captured the mood of the times well in his 1995 survey exhibition, A Very Peculiar Practice. Gathering together “aspects of recent New Zealand painting”, including Tuck’s, he called on artists to “allow the hidden laughters and redundancies of history to converge and mingle” and to cultivate “careless attentions and sweet disorders”,2 suggesting that the “end of painting is only a resumption … a question of dismantling so as to construct it better”.3 Tuck must have absorbed these injunctions, but the next steps were still hard fought. Remember, Echo lost the power of speech, she could only repeat the words of others. Narcissus fell in love with his own reflection and died in thrall to a mirror image; Adam and Eve were banished from the Garden of Eden.

Barbara Tuck Iris Gate (detail) 1999. Oil and encaustic on canvas, six panels. Courtesy the artist and Anna Miles Gallery

Another key to this body of work is the source for her title. ‘Iris gate’ is a phrase lifted from a poem by Michele Leggott, published that same year, in a collection titled as far as I can see.4 ‘A woman, a rose, and what has it to do with her or they with one another?’ is in seven searing parts, taking the reader through a series of ‘gates’ that track her descent into sightlessness. Facing the consequences of a degenerative eye condition, Leggott writes in the third stanza, “At the iris gate I leave the world above for the world below”.5 There is melancholy and anger and fear in this journey into darkness, but throughout it is charged with brilliant flashes of colour and light, a felt sense of the world: the sea, mountains, the sun and moon, her family. Early on she asks: ‘‘What is the sight of my eyes to the great oratory of the labyrinth?” and imagines herself on a mission to “open the eyes of the soul”.6 For Leggott vision is both sensation and memory, now rendered palpable through other senses: touch, smell, feeling. It is a state that must now be conjured with words.

The ‘iris’ of Iris Gate is for Leggott: “I, a pupil, a taut aperture and nimble, distinguishing abundance in the field from a chaos in the world”.7 How beautifully this captures the feel of Tuck’s painting. There is no one-to-one relation between poem and picture, but perhaps the woman in a red dress approximates the figure conjured in this verse, who might double as the artist in the world at that moment. Clothed in modern garb her pictorial source is elusive. Perhaps she is a product of the artist’s inner eye. Barefoot on her painted ground she stands ready and attentive. Through her bare extremities she is in touch with her medium; head slightly tilted, her piercing look seems also to be a listening. The pause within which Iris Gate was made is here made palpable. This figure seems stalled, but also intensely alert, poised as Allan Smith would say between the “accepted codes of painting practice and messages from the world around [her]”.8

This essay was first published in Christina Barton and Anna Miles (eds.), Barbara Tuck: Delirium Crossing, Te Pataka Toi Adam Art Gallery, Wellington; Anna Miles Gallery, Auckland; and Ramp Gallery, Hamilton, 2022.

“Impasse after impasse” is a phrase used by Anna Miles in her exhibition text for Barbara Tuck: Iris Gate, Anna Miles Gallery, Auckland, 2014.