Ka Mua Ka Muri

Walking Backwards into the Future

Ana Iti Treasures Left by Our Ancestors (still) 2016. Single-channel digital video, colour, sound, duration 4 mins 40 secs. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2019

Our histories are always with us, but who is telling the story? The Gallery’s new collection hang, Perilous: Unheard Stories from the Collection offers up a range of different perspectives on how the past and future might intersect, and invites us to rethink how we commonly see our heritage. Here, the exhibition’s curators have each selected a work from the exhibition for a closer look.

Glukupikron

Kushana Bush Glukupikron 2020. Gouache, watercolour, metallic gouache on paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2020

Some stories are about things that happened; others are fabrications from start to finish. Perhaps the most compelling are a mixture of both. Kushana Bush’s paintings, for example, weave together an intoxicating tangle of invention and illusion. What’s true and what feels authentic are not always the same thing, and – as Bush knows well – even the most carefully plotted stories have a way of getting away on you, of deciding exactly how they want to be told.

Glukupikron, recently added to the Gallery’s collection through the support of a generous donor, was born in strange, uncertain days. In late March 2020, as Aotearoa battened down the hatches for our first Covid lockdown, Bush hurriedly packed up her Dunedin studio and headed home with her easel. Once there, instead of looking for comfort in contrast, she doubled down; seeking out podcasts and paintings inspired by another pandemic – the bubonic Black Death that devastated parts of Asia, Europe and Africa in the fourteenth century. She saw this research, and the resulting drawings, as a natural way to process the events unfolding around her: “During wars and pandemics, artists throughout the ages have sublimated their fears and uncertainties into images.”1 As an artist known for intense and psychologically fraught paintings, there may even have been a sense that world events were catching up with her: “I always saw the world in flames, now everyone else sees it that way, too.”2

Reminders of the turbulence bearing down outside reverberate across Glukupikron. Swirling waves and weirdly animate rocks offer perilous footing to an unruly assembly of animals and people. In the centre, two bulls thrash wildly as their human riders fight vainly for control, while other figures gather in pensive groups, clutching at ropes and each other. Set against twisting clouds that could be tornadoes, explosions or distant bushfires, the oppressive mood darkens still further when you notice the body bag, incongruously wrapped in chic Hermes.

Yet Glukupikron (taken from a Greek word that translates as ‘sweet-bitter’) isn’t unrelentingly bleak. Bush leavens it with her usual deft humour, stashing items of relatable banality – loosely tethered essentials (spray bottle, toothbrush, banana), orange-handled scissors, a flash of undies – across its shimmering, elusive surface. And while signs abound that humanity’s hold on power might be slipping away, the natural world – with its leaping fish, glossy kereru and wriggling frogs – appears newly rejuvenated. Belonging to the classical world as much as the contemporary, Bush’s strangely out-of-time images convey a sense of overlapping histories, of hubris and self-delusion compounding across the centuries. As a species, we’ve often been slow to read the writing on the wall, but it’s a skill needed now more urgently than ever.

Felcity Milburn, curator

Still Light

Nova Paul Still Light (still) 2020. 16mm film transferred to digital video, colour, sound, duration 6 mins 35 secs. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2020

My work is always rooted in the particular circumstances of my domestic life, the objects, clothes, toys, cups, flowers, that speak of myself, my child, my husband and the house, garden, land, that frames my life.

So wrote Joanna Margaret Paul (1945–2003) in the catalogue for the exhibition Woman’s Art: An Exhibition of Six Women Artists in 1975. This statement is apt when considering Still Light, a video work by Nova Paul (Ngāpuhi, Te Uriroroi, Te Parawhau, Te Māhurehure ki Whatitiri) created four decades later that responds to a poem by Joanna Margaret Paul. Nova’s Still Light and Joanna’s painting Barrys Bay: Interior with Bed and Doll (1974) both focus on the domestic setting and resonate strongly with each other, something I’m looking forward to seeing when they are hung side by side in Perilous: Unheard Stories from the Collection.

The subtle, grainy effect of Nova’s 16mm film has much in common with Joanna’s 8mm films; not only the technical qualities inherent in film, but also the domestic environments they bring into focus. Light is a central theme for both artists, the way it infuses an interior from the outside, falling softly across a room. The interior becomes a duality of a space – the humble kitchen table with still life becomes subject as well as metaphor for both artists. Nova’s Still Light includes a beautifully crafted sound piece by her friend and collaborator Bic Runga. It’s a tender song to accompany a tender artwork.

The kitchen table has a central presence in both artists’ work. I’ve always enjoyed the idea of art being made around the kitchen table; it’s the heart of the home where we come together to eat, drink, play cards, blow out birthday candles, display flowers from the garden in favourite vases and place bowls of fruit. Most recently, many of us have sat at our tables tapping away on our computers when working from home in these Covid times. The table is also a place where an artist can work with ease in ‘domestic mediums’, particularly watercolour and drawing. The garden makes its way inside; flowers and fruit are arranged, connecting outside and inside spaces in both Nova’s Still Light and the recent gift of a beautiful still-life drawing by Joanna from Roger Collins, a friend and supporter of the artist.

Made in direct response to an untitled poem by Joanna, Nova’s Still Light also shares a domestic still-life tradition with the work of several generations of women artists in Perilous, including Joanna herself and the still-life drawings and paintings by earlier artists, Rita Angus, Frances Hodgkins and Margaret Stoddart.

Peter Vangioni, curator

Treasures Left by Our Ancestors

Ana Iti Treasures Left by Our Ancestors (still) 2016. Single-channel digital video, colour, sound, duration 4 mins 40 secs. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2019

Ana Iti (Te Rarawa) made Treasures Left by Our Ancestors in response to two permanent exhibitions at the Canterbury Museum: Iwi Tawhito–Whenua Hou / Ancient People–New Land and Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho o Nga Tupuna / The Treasures Left to us by our Ancestors. In these life-size dioramas, instead of providing information on the complex history and lives of southern Māori, tangata whenua are depicted as primitive stereotypes, in particular as part of a simplified moa hunter narrative. Misrepresentative and lacking research, the exhibits fail to show the indigenous knowledges, advanced migration, art, architecture, tools and practices that were developed and flourished in pre-colonial Aotearoa.

Ana’s video work captures the artist crouching in front of the controversial displays, positioning her contemporary body in relation to these constructed scenes, while museum visitors walk nonchalantly past. In an attempt to understand this version of history, she literally gets on the level of these tūpuna (ancestors), who are rarely shown standing. With this act, Ana critiques how public information about indigenous people and culture is created and disseminated through museums.

Displays such as these are often presented and perceived as factual even though museological narratives and histories are generated from Western knowledge systems and are not necessarily the whole story. Museums in Aotearoa were established from the mid-to-late nineteenth century and became a way of collecting Māori art and taonga (treasures) that were acquired by Pākehā through gifts, trade or theft.3 Ethnological collecting was seen as a political tool of governorship. As art historian Roger Blackley states:

At the same time as they annexed the actual Māori land, European settlers appropriated the distinctive history and culture of Māori, both for a readymade ancient history of the islands and as a unique decorative signifier for an inchoate settler identity.FTN-4

Acquired and presented in the context of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Treasures Left by Our Ancestors reminds us that like museums, art galleries are also integral to the process of colonisation. From the late nineteenth century, art galleries operated in Aotearoa to exhibit European painting and sculpture as well as works from the settler coloniser art societies that had formed around the country from 1869. These institutions were introduced as part of the colonial project, as an assertion of European culture, and the collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū reflects this legacy.

This is not the first time the Canterbury Museum dioramas have been challenged. Ngāi Tahu leaders have refuted their presence for many years and members of the public have also voiced their concern. In 2020, a vinyl label was installed partly covering one of the displays, claiming that the museum has made a commitment to work with Ngāi Tahu to replace them. In Treasures Left by Our Ancestors, Ana crouches in front of the dioramas for as long as she can physically hold the pose, a test of endurance. Her persistence echoes the ongoing mahi being undertaken towards asserting sovereignty and a ReMāorification of institutions and collections.5 Treasures Left by Our Ancestors demonstrates that we have a long way to go.

Melanie Oliver, curator

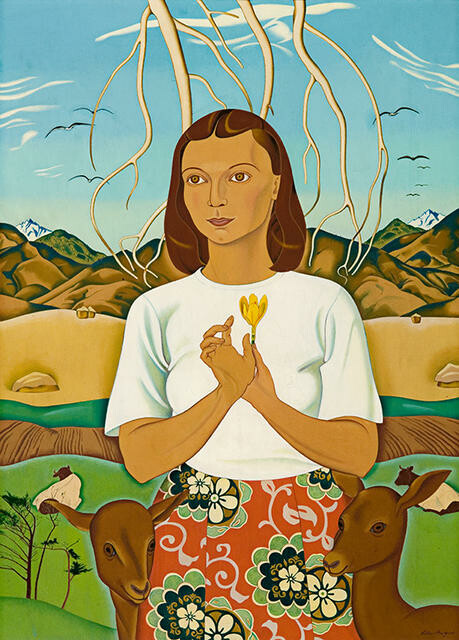

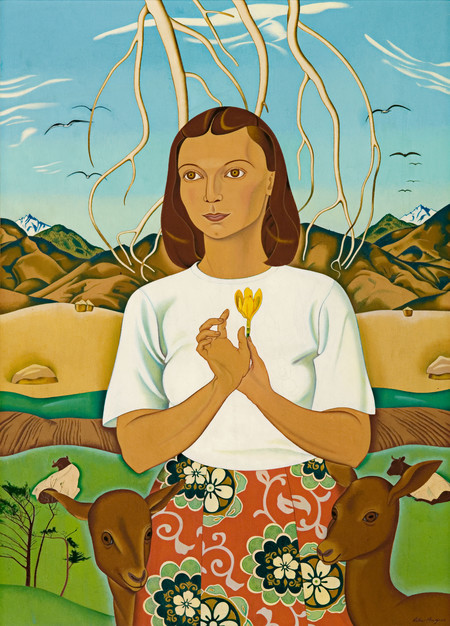

A Goddess of Mercy

Rita Angus A Goddess of Mercy 1945–47. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1956

“I have taken stronger monastic, pacifist vows,” Rita Angus wrote in May 1945 to composer Douglas Lilburn, her close friend and support whose personal history was now inextricably linked to hers.6 A Goddess of Mercy – the first started of her three goddess paintings – was already mapped out on 8 May, VE Day, celebrating Victory in Europe, the day after Germany’s formal surrender to Allied forces in Reims, France. As she later wrote to Leo Bensemann, “Most of the idea of this painting was blocked in, just before and during the week, peace was declared with Europe.”7

In June, Angus left her hillside cottage on Clifton Hill above Sumner Beach, to appear again in court before the Manpower Committee for refusing to enter war work. With global conflict winding down, however, and many servicemen returning home, Angus was fined one pound instead of the usual far heftier penalty. Forging ahead in July, she told Lilburn:

As a full-time painter, I am proceeding with the various stages of my large canvases, the major works of my lifetime. I hope to complete these in the next three years. … These canvases when painted, will not count much, if anything to an older, or my own generation. I paint for the next two generations. … I hope now to work quietly and undisturbed.FTN-8

In 1944 Angus had suggested to Lilburn that their future artistic productions and goddess portraits especially be seen as symbolic off spring of their relationship.9 Following their brief love affair at the end of 1941 and her miscarriage in January 1942, Angus’s attempt to reconcile loss extended to the notion of their child’s spirit living through their art. More accessible ambitions came with the work’s completion and reproduction in the 1947 Year Book of the Arts in New Zealand, including:

To show to the present a peaceful way, and through devotion to visual art to sow some seeds for possible maturity in future generations. … As a woman painter, I work to represent love of humanity and faith in mankind in a world, which is to me, richly variable and infinitely beautiful. … My paintings express a desire to … create a living freedom from the afflicting theme of death.’FTN-10

This she echoed in a letter to Bensemann, describing it as showing “the pull between life and death, with the triumph of the living, over the dead. ‘Ruth’ is the woman, and the painting ‘lives’.”11 Being receptive to broad philosophical and cultural influences, Angus’s reference was the beloved Gentile woman who joined the Israelites to follow the Biblical Yahweh.

Reflecting what painter Douglas MacDiarmid later described to Angus biographer Jill Trevelyan as “The cosmic bouillabaisse of philosophic stew … from a recipe exclusively Rita’s”, its title also shows her interest in Eastern thought, specifically in Kuan Yin (or Kannon), venerated in China (and Japan) as a goddess of mercy.12

Angus also explained this work as a memorial to her sister Edna, who had died of an asthma attack on Christmas Eve 1939, seven weeks after her marriage.13 Wearing a Chinese-inspired fabric skirt based on Edna’s housecoat, she is part idealised everywoman and part self-portrait. The likeness, however, is more Edna’s than Rita’s.

Ken Hall, curator