Post Hoc

It is mid-summer in Venice, and the pervasive cacophony of cicada song cuts through the heat and oppressive humidity. New Zealand’s presence at the 58th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia is housed within the former headquarters of the Instituto di Scienze Marine, the Palazzina Canonica. Located on the Riva dei Sette Martiri, on the southern edge of the island, it is only a few hundred metres to the entrance of the Biennale’s Giardini, with its permanent national pavilions.

The Palazzina, a neo-Renaissance building that faces out onto the water, has reopened to the public for the first time since the 1970s following a restoration in 2017. Jutting out onto the Riva, it is elegantly proportioned, with string courses and pilasters of terracotta-coloured brick framing a yellow-cream façade, marble entrance, balcony and lozenge features. A columned portico links the Palazzina to a stand-alone building containing the ‘engine’ of artist Dane Mitchell’s Post hoc project:1 a tapered, steel anechoic chamber.

Entering the pavilion through a heavy gate swung between a robust decorative iron fence, I encounter the first of three pine trees, or rather ersatz pines – three “stealth cell towers” placed among the foliage of the Palazzina’s garden, underneath larger versions of the real thing. These trees are proprietary objects, manufactured by a company in Guangzhou, China, and are designed to provide camouflage – however rudimentary – for the communication equipment they house. In proximity to these trees an automated female voice, complete with received pronunciation and perfectly uniform inflection, can be heard.

Object sighting 23 February 2008, El Paso, Texas, United States

Object sighting 23 February 2008, Florence, Texas, United States

Object sighting 23 February 2008, Kovin, Serbia…

Eight hours a day, six days a week, for nearly seven months, averaging 15,000 words per day.2

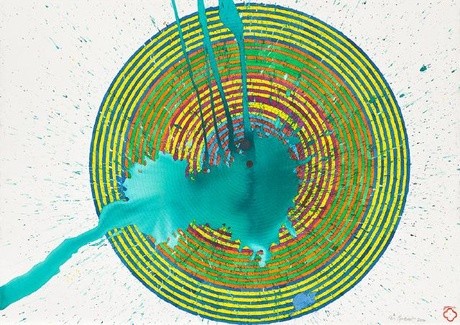

These cell tower trees act as base transceiver stations for a broadcast that originates in Mitchell’s anechoic chamber; a structure fabricated in Venice and modified to allow visitors to peer inside via a large viewing window at the rear. Its interior, lined with acoustic foam designed to eliminate echo, contains a microphone and a speaker – the origin of the voice – and is fed data via a nearby server rack cabled in to the structure. The chamber acts as the central component of the project, its broadcast relaying a seemingly unending list of entities that have been erased from existence, or otherwise constitute an absence. There are 260 lists, of many and varied things that have disappeared: extinct languages, things that melted, obsolete tools, bridge failures, submerged atolls, failed banks, retreating glaciers...

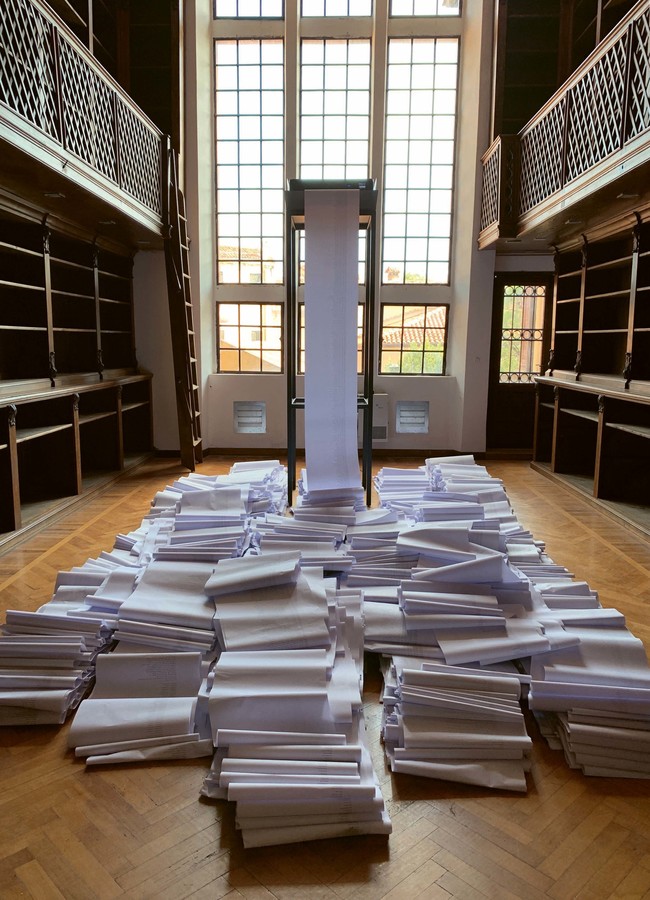

Housed within the Palazzina itself, in the emptied-out library of Adriatic Studies on the first floor, a printer on a tall stand tirelessly prints the lists of entities that no longer exist. From huge rolls of paper, they cascade down the height of the stand to the floor of the library. Over time the paper accumulates in folds and waves. Walking around this component of the installation, it is possible to read particular lists, but due to the way the paper amasses, only fragments can be discerned. Over the course of the Biennale this accumulation of paper will stand testament to the passing of time as well as providing tangible evidence of loss through the build-up of material in sculptural form.

Mitchell’s Post hoc is intended, in his words, as a “contagion”;3 a work that extends beyond its physical boundaries. The core of the piece sits within the grounds of the Palazzina, but through the considered placement of four additional cell tower trees around Venice the work becomes an invisible sculptural field. These errant pines create a nodal network that covers the city’s historical centre. Each emits a WiFi signal, through which visitors can view the entire list of categories of bygone things on a handheld device, then listen to a selected list read by the same automated voice.

Mitchell’s cell tower trees have the ability to carry both real and symbolic transmissions:

What was interesting for me was to think about an object (a sculpture in the Venetian landscape) as being the transmitter of a signal – a real and metaphysical signal – that is, something that produces a signal which is transmitted into the world that creates perturbations in a field of experience.4

The use of language (a signal, a contagion) surrounding the cell tower trees suggests both the organic and anthropogenic, or perhaps the immaterial language of pure datascapes – viral algorithms and light on the invisible spectrum:

These rather antagonistic objects doubly affect the environment: they infect the landscape with an object which, in an attempt to go unseen whilst also producing a transmitted signal that is everywhere and nowhere, spreads itself across the cityscape.5

This ‘hiding in plain sight’ (to use the title of a previous work of Mitchell’s that also used a cell tower tree) is reminiscent of another piece of essential infrastructure that keeps us yoked to global wireless connectivity: the data centre. James Bridle, in an examination of these anonymous buildings, writes:

[T]ypical examples are nondescript office buildings with mirrored or shuttered windows, deliberately dull to the point of deflecting unsought attention; or vast, distripark-style groundscrapers... the size of football fields, but marked with few clues as to their actual functions, the epitome of the big box.6

The double-bind for these examples of post-industrial infrastructure is how to exist in the world without attracting attention to themselves; in their attempts to go unnoticed, they do precisely the opposite. In the case of the data centres it is their sheer size and disconcerting lack of identifying signifiers that make these buildings so salient. With the tower trees, it is their obviously pre-fabricated and alien appearance when they attempt to blend in with a forest of the real thing. In both cases the vaporous nature of the internet as everywhere and nowhere is signalled by its presence in urban and natural landscapes as uncanny analogues.

A week or so before I departed for Venice, I read a chapter in a novel in which the protagonist and his accomplice are in a spacecraft docked off a gigantic orbiting space station. The space station produces artificial gravity, sunrises and earth-similar climates for the beautiful and moneyed leisure class, who opt for recreation above an earth straining under violent resource-expending megalopolises. Kicking off walls to move through the craft’s ultra-modern interior in zero-gravity, they come upon something incongruent:

From somewhere ahead, Case made out the familiar chatter of a printer turning out hard copy. It grew louder as he followed Maelcum through another doorway, into a swirling mass of tangled printout.7

It was a serendipitous passage to come across; this novel is set in a near-future where inequality is rife and the all-pervasive technologised present sits atop the cultural detritus of the past. But somehow these relics persist: the mechanised chatter of an archaic printer, the articulated whirring of a dirty pink plastic prosthetic arm, abandoned rooms full of broken cathode ray tube televisions thick with the smell of dust, the old buildings that sag under the weight of megastructures upon megastructures. This paradoxically in a world where the immaterial is favoured above all else: data is currency and the ultimate remuneration, and its inhabitants prefer to spend their days in the “consensual hallucination” of cyberspace,8 rather than face the grim hustle of IRL.

Besides the mass of material that accumulates beneath the printer (twenty kilometres of paper will build up strata-like on the floor of the library by the end of the Biennale),9 the incessantly speaking voice is what gives Mitchell’s project its decidedly post-human quality. And in thinking about the lists that catalogue extinctions, it is inevitable that a consideration of the fate of humanity as a species should arise. The voice has perfect pronunciation and diction – never stuttering, mispronouncing or stalling. However, there is an uncanniness to its utterances. The cadence isn’t right; it has a quality that no human would mistake as belonging to another. Similar voices operate as messengers in the public sphere. Most of the time they dispense mundane information on the quotidian: the departure and arrival times of buses and trains, instructions at self-service supermarket checkouts. They are electronic servants to assist us in our day-to-day lives. But in the voice that issues from Mitchell’s trees, along with the printer that chatters incessantly, there is a sense that these machines have been left to continue with their programmed duties in a world now absent of a guiding human hand.