Caveat Collectors

Birds, Extinction and Bill Hammond

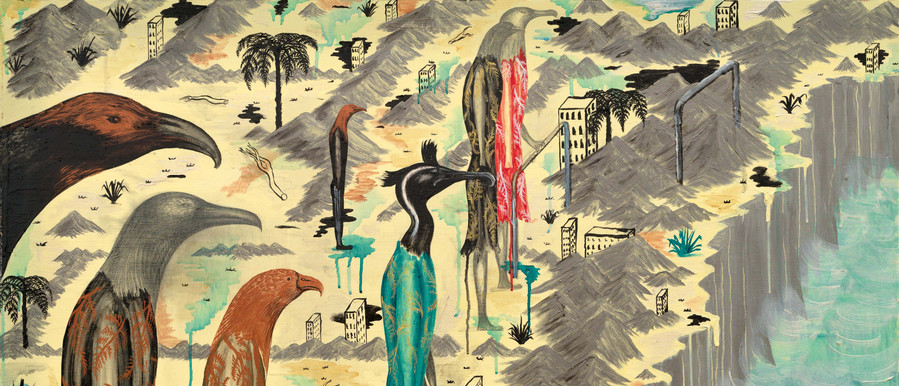

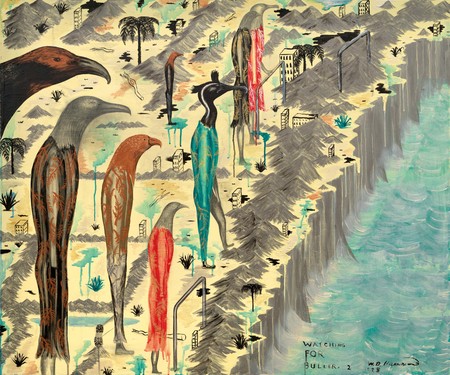

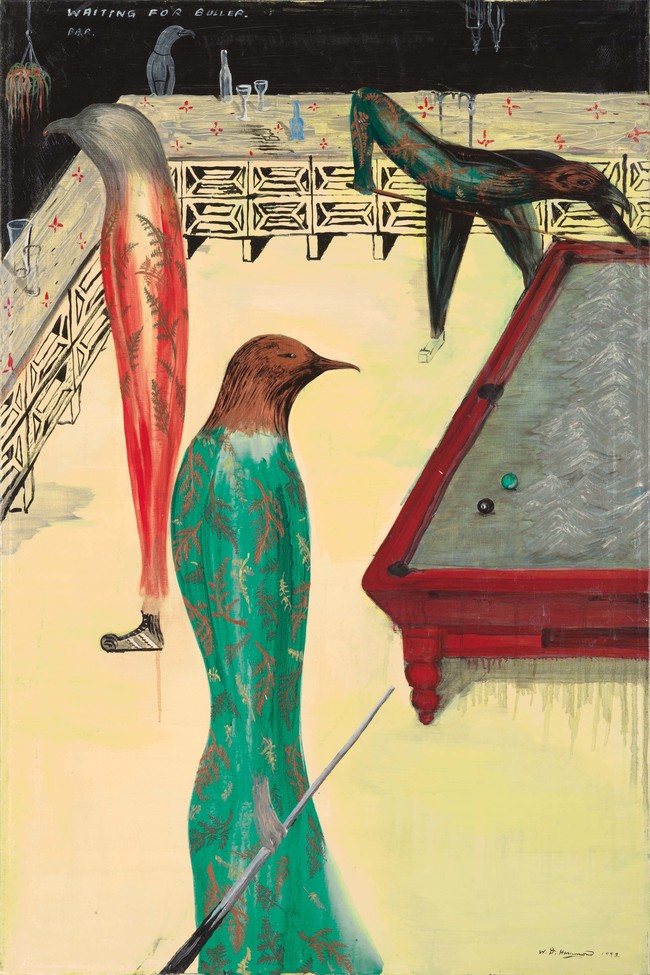

Bill Hammond Watching for Buller. 2 (detail) 1993. Acrylic on canvas. On loan to Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū from the artist

Extinction has claimed nearly fifty per cent of Aotearoa New Zealand’s bird species over the past 650 years. The persistent myth has it that European settlement in the nineteenth century swept away a pristine past. And most obviously, because we know their names and can catalogue (literally) their infamy, that story includes the professional bird collectors as the cause of those extinctions.

Pre-eminent amongst the Aotearoa New Zealand collecting fraternity was Walter Lawry Buller. He courted and often tried to pre-empt the activities of the greatest collector of them all, Lord Walter Rothschild. As collectors, both were men of their time. Rothschild was rich enough to have his own museum and fund dozens, even hundreds, of collectors around the world, including Henry Travers and others in Aotearoa New Zealand. Buller, born in the fledgling colony, was desperate to be recognised by Britain’s elite. And to climb the social ladder he made the most of his position on the ground, collecting birds himself and receiving the donations of a pioneer population.

European settlers explored, cleared more forest – earlier Māori fires had removed most of the dry forests already – ‘broke in’ the land to farms, and searched everywhere for mineral wealth. All handy with rifle and shotgun (and imbued with a God-given sense of superiority over birds, beasts and the land), they needed to eat, and the forests were still full of pigeons and kaka.

This history of Aotearoa New Zealand’s birds, their declines and extinctions, now underwrites most people’s perceptions. Artist Bill Hammond recognised, explored, and visually explicated how deeply birds, living and dead, are embedded in our culture. And Buller became, for Hammond, an architect of extinction and a focus of great art.

But as usual, ‘obvious’ causes are not the whole story, or even a major part of it. Focusing on collectors as cause of extinction both finds easy targets – scapegoats – and obscures an unpleasant reality. That reality is that human settlement itself, its processes and progress, exterminated birds. The collections are visible, grisly testament to extinction for some species, and for the depletion of most others. The depredations can be counted in museum drawers, and for a few species collectors were the final twist in the knife of human occupation. But the ultimate irony is that without Rothschild’s legion of collectors, and Buller and his contemporaries doing their bit here, we would have very little idea at all of the diversity of wildlife in Aotearoa New Zealand (or on the planet in general for that matter) before mankind multiplied exponentially in the twentieth century and obliterated most of the wilderness in the process.

Collectors are uncomfortably easy targets that cover our collective very human guilt for bringing in foreign predators, burning the once-ubiquitous forest, and, ultimately, converting most of accessible Aotearoa New Zealand to our uses. Reserves are fundamentally what we didn’t want to, or couldn’t, bring into production.

Bill Hammond Watching for Buller. 2 1993. Acrylic on canvas. On loan to Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū from the artist

Close by, Norfolk Island is a stark example of the mistake of putting the blame for collective action on collectors. Early Polynesians on the island ate everything from seabirds to the island’s own species of blackbird. They introduced the kiore / Pacific rat and left, leaving the rat to

quietly go on preying on the birds, lizards and bats. Then, a bare fourteen years after James Cook’s visit in 1774, Britain began landing its felons and free settlers on the island to feed a nascent and hungry Sydney. In the 200 years since, the island has been denuded of its forests, and cats and more rats introduced. But the decline to near extinction of the world’s largest white-eye, unique to the island, is blamed by locals on Roy Bell. Bell grew up on Raoul Island and made his living collecting birds and other natural history specimens. And yet, judging from the skins preserved in museums, he killed in total only a few percent of a year’s breeding output. Settlement, not Roy Bell, killed the white-eye.

As on Norfolk Island, so in Aotearoa New Zealand. Two waves of occupation, first from Polynesia and then Europe, eliminated the birds. Māori had no ‘collectors’ as such, except when acquiring choice feathers for cloaks and ornaments. But Māori and Europeans alike needed living space without forest, and food. Māori ate all kinds of birds, from moa and eagles down to robins and parakeets. European settlers concentrated on the game that was left, such as ducks, kereru / pigeons and kaka.

Of the nearly fifty per cent of Aotearoa New Zealand’s bird species now extinct, from wrens to Haast’s eagle and moa, most went extinct in the interval after Māori settlement and before Cook’s arrival; European settlement erased the remainder, some of which, like the huia, were already in deep trouble. The huia had vanished from most of Te Ika-a-Māui / the North Island before European settlement, but was still thriving in strongholds in the Ruahine and Tararua mountains and the forests of the Wairarapa.

That hundreds of huia were shot to feed the craze for wearing its tail feathers after the Duke of York had one placed in his hat band in 1901 has been blamed for its final demise. But the species’ main surviving population was probably in the Wairarapa’s ‘Seventy Mile Bush’, which was felled and burned for dairy farms during the 1870s and 1880s under Premier Julius Vogel’s development programme. The people who cut and burned the forest saw huia as just common birds around their homesteads. Vogel is ‘bird’ in German, so the Premier who promoted immigration by Danes – hence Norsewood and Dannevirke – to turn the Seventy Mile Bush into milk and butter was unconsciously destroying his own. But the implications for Nature have never trumped humankind’s wants.

Haast’s eagle was the largest known. Here the skeleton of a female’s talons are compared with those of a golden eagle. (c) Rod Morris. Image courtesy of Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand

So if, as we know, nearly half of our bird species are now extinct, and, as we suspect, some species were very abundant before human settlement, how come our surviving forests now support so few species and individuals? The highly dynamic pre-human ecosystems were driven partly by nutrients brought in by hundreds of millions of burrow-nesting petrels: seabirds that harvested their food from half the world’s oceans. Most of their hill-country colonies had gone before the Endeavour entered Tūranganui-a-Kiwa / Poverty Bay, but their legacy nutrients supported high-country farming into the 1950s.

There were few open areas before humans arrived. Indeed, before the fires that accompanied Māori settlement, forests covered most of eastern Te Waipounamu / the South Island. A road from Christchurch to Hanmer 600 years ago would have passed through highly productive native forest all the way. Food for thought on your next trip to the hot pools.

The diversity and numbers of birds and reptiles would be staggering to modern eyes. Offshore islands hint at that abundance. On the Poor Knights, east of Te Ika-a-Māui / the North Island, there are thirty korimako / bellbirds to each hectare, not hectares per bellbird like on the mainland. Joseph Banks was woken by the dawn when the Endeavour was anchored 400m offshore in Totaranui / Queen Charlotte Sound. This speaks to the abundance of the bellbirds, tui, kokako, piopio and kaka in 1769. But by then much of the damage had been done.

Banks did not visit nearby Stephens Island, where the variety and abundance would have amazed him even more; almost all Te Waipounamu / the South Island’s forest bird species had thriving populations in its one hundred hectares or so of low coastal forest. There were ten piopio to the hectare alone in 1894. This rich ecosystem was nourished by the millions of petrels that burrowed in the thin soil covering the sterile rock. Isolated since the most recent Ice Age waned and rising sea levels cut off the island about 10,000 years ago, its intact forest ecosystem was the last still functioning as it had before humans reached these shores. And it was devastated in sight of the nation’s capital by progress, by our need to make the seas safe for navigation.

Fewer than twenty skins of Lyall’s wren have been preserved. Originally in Buller’s collection, these two are held in the Canterbury Museum collections. The collector is unknown but from the collection date, it may have been H.H. Travers.

Lyall’s wren (or Stephens Island wren) survived only there, safe from the kiore / Pacific rat that had killed off its mainland populations along with three other species of flightless or near flightless wren. Cats arrived with the lighthouse keepers in 1894 and bred freely: by 1900 there were hundreds on the island. Hordes of cats (and not the collectors who shot the dozen or so wrens now preserved in museums around the world) killed off the wrens, as well as the island’s own special piopio, and the tīeke / saddlebacks, the mohua / yellowheads, the mātātā / fernbirds and most everything else. But the story everyone, everywhere, remembers is that one cat – “the lighthouse keeper’s cat” – exterminated the wren.

Stephens Island still has large populations of (mostly small) petrels. Up to a tonne of tuataras live on the insects and lizards supported on each hectare by the seabird guano. But the island’s ecosystem no longer shows us what Aotearoa New Zealand was. It is a shell, a monument to the inadvertent effects of settlement: the land birds were collateral damage.

On the mainland the lost ecosystem we know most about is in the now-human ecosystem of North Canterbury, epitomised by the iconic site of Pyramid Valley: before humans arrived it was the richest and most productive region in Aotearoa New Zealand. Today’s sheep, dairy cattle and vineyards give no hint of the landscape 1,000 years ago. Back then, Haast’s eagle preyed on four species of moa in a forest that recycled its nitrogen as fast as the Amazon rainforest does today. That prodigious productivity supported fifty species of bird, as well as tuatara, hordes of lizards and bats. The world’s largest eagle and its second largest harrier hawk, nearly as big as a golden eagle, topped the food chain.1

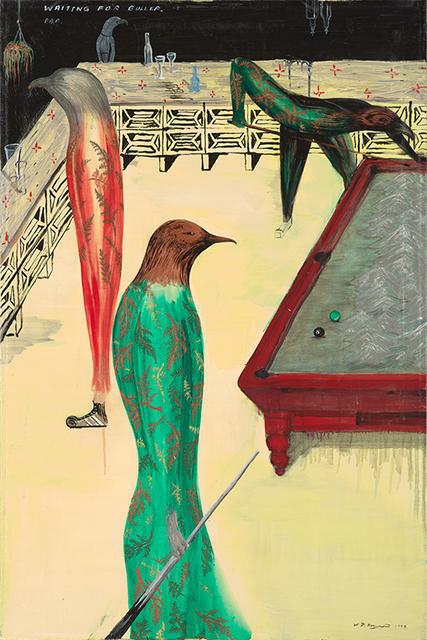

Bill Hammond Waiting for Buller. Bar 1995. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1996

The two waves of extinction that changed that rich system with its native birds into the manmade landscape today, populated mainly by European and Australian birds, also took something unique from the planet, not just from Aotearoa New Zealand. They removed the last remnant of an ecosystem that died out everywhere else 65 million years ago.

Birds are dinosaurs: these islands were the last place on earth where the big predators and the big herbivores were all dinosaurs, while tiny mammals – short-tailed bats, which spent a lot of time foraging on the ground – scuttled around their feet. Mammals ruled everywhere else, but in Aotearoa New Zealand the Age of Dinosaurs ended only 650 years ago.

So, it is in the deepest sense that it is appropriate that our culture has embraced birds as symbols both of the nation and especially of the natural world. Our common notions of how and why so many birds were lost may be wrong, just balms for the communal conscience, but the extinctions and their seeming inevitability are powerful symbols of the fragility of the natural world. And our relationship with that ultimate truth has been the subject of Bill Hammond’s work for many years. His art is a mirror to our guilt in always destroying what we love just by making a living on this planet.