Bill Culbert Bebop 2013. Furniture, fluorescent tubes, electrical components, wire, sheet glass. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with assistance from Gabrielle Tasman and the Christchurch Art Gallery Trust, 2014. Reproduced courtesy the Estate of Bill and Pip Culbert

Raising a Glass

Remembering Bill Culbert

Bill Culbert died aged 84 on 28 March this year at his home in the Vaucluse region of Provence. Built from dilapidated farm buildings on a small hilltop at a deserted hamlet called Croagnes, it’s a home that he and his wife Pip began to establish in 1961. Then, the region was a sparsely populated economic backwater – the Culberts bought the hilltop buildings for just £100. In the valleys and on the surrounding slopes were a few small vineyards and farms. A 1962 painting, Gerard Going to Work, shows their neighbour, the farmer Felix Gerard, trudging off down the stony hillside wearing a wide- brimmed hat like the one worn by Vincent van Gogh at Arles.

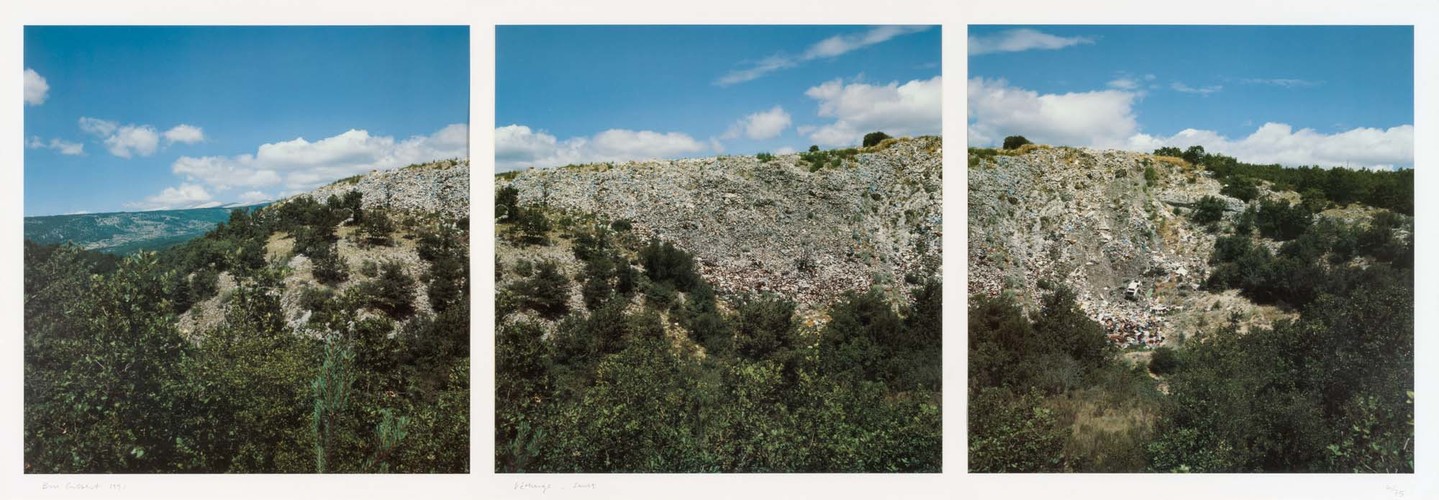

From Croagnes, the view rose northward towards the slopes of a steep escarpment near Sault on the high Plateau d’Albion, down which spilled the discarded rubbish of a décharge or tip – there’s a triptych colour photograph of the site in the collection of Christchurch Art Gallery, Décharge, Sault (1991). This tip and many like it were cleared away after 1992 when a landfill tax finally doomed the rural décharges and the region became fashionable – and very expensive. But when the frugal Culbert family began to fix up the tumbledown buildings at Croagnes the tip was a vital source of recycled materials.

Culbert himself regarded the tips as historic sites with links back to Neolithic culture. In a vital sense, what he was recycling in the process of fixing up and furnishing the house at Croagnes was also the fragmentary traces of stories that had passed out of meaningful use in the midden – he was recycling their meaningfulness as well as their usefulness.

The tip also became a source of materials for many of his artworks, such as the melon-harvest box of Box 1 (1974). These works combine the sense of recovered stories with the idea of the found object, whose origins are often sourced to Pablo Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912). In that work a printed image of chair caning is pasted on the surface of the painting, becoming integral to the work’s governing topic. More pertinent in Culbert’s case, however, is Marcel Duchamp’s entirely autonomous Bicycle Wheel of 1913, which announced itself as a work of art by being mounted blithely on a plinth. Culbert’s strategy – engaging and even affectionate compared to Duchamp’s critical irony – has often been to light the object with electric bulbs, fluorescent tubes, direct sunlight or natural light reflected in various ways. Sometimes his interest has been as much in the effects of shadows as of light itself. These strategies are often very simple, as for example in Bucket, Croagnes (2012) in which a plastic bucket is filled with sunlight. They can also be complex and jazzy, as in Bebop (2013), part of Culbert’s large, multi-component work for the 2013 Venice Biennale, Front Door Out Back. The mid-century chrome and Formica tables and chairs that seem to be dancing pell-mell towards some unknown destination were design favourites of Culbert’s, but their provenance as narrative recoveries and the brand- name ‘Bebop’ also coincide with the arrival in Provence of many Algerian ‘Pieds-Noir’ – people with French settler origins who fled or were expelled from the colonial territories after the end of French rule. The brand-name references bebop jazz, a Culbert favourite, and the recycled Bebop table implicitly puts back into circulation or at least embeds a fragment of the lost story of the Pied-Noir family that had owned it.

In 1991, as if anticipating the demise of the tips, Culbert held an exhibition at the Galerie Froment & Putman in Paris with the title À Charge de Décharges. The title can be understood in a variety of ways. Culbert himself enjoyed the possibility that he was ‘charged up’ (like a battery) by the tip, and also the meaning ‘on condition of’, implying that in using the resources of the tip he was repaying its largesse. The recycling of materials in Culbert’s art implies a kind of return journey, not in any literal sense but rather, as Jerôme Sans wrote in his catalogue essay for À Charge de Décharges, quoting Paul Virilio, as watchful archaeology, as being on the lookout for “whatever has been silent that will now speak, whatever was shut that will now open up”.1

Bill Culbert Décharge, Sault. Photograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1991. Reproduced courtesy the Estate of Bill and Pip Culbert

Though it would be an excessive stretch to see the jostling queue of Bebop as representing at some level the arrivals of refugee Pieds- Noir from Algeria, other works by Culbert – not least his collaborations with Ralph Hotere – have clear political narratives in respect of “whatever has been silent that will now speak”. The Gallery collection contains a number of lithograph drawings referencing his large floor- based collaboration with Hotere, Pathway to the Sea – Aramoana (1991), protesting at the proposed aluminium smelter at the Otago Harbour heads. Another example of Culbert giving voice to silent or silenced subjects is Stand Still (1987), a selection of seven mundane objects, such as a plastic bucket, mounted on upright neon tubes, which represent ordinary citizens commanded to halt and ‘stand still’ on the Protestant and British lines in the town of Derry during the Troubles. The ordinariness of the found objects is poignant, but also wryly subversive given the simple splendour they have had bestowed on them by the neon tubes. The front window of the Culberts’ house in Putney, London, has a standard lamp in it made of a lamp stand with a plastic bucket instead of a lampshade. Though not declared as a work of art, like the self-deprecating objects in Stand Still the bucket glows with a kind of emancipated dignity.

Bill Culbert Bucket, Croagnes 2012. Photograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the artist, 2014. Reproduced courtesy the Estate of Bill and Pip Culbert

In 1978, having left New Zealand in 1957 after four years at the Canterbury University College School of Art, Culbert returned to Christchurch as a visiting fellow. Among the several works he made during his tenure are Blackball to Roa (1978), a kerosene tin pierced by a fluorescent tube. This type of tin would certainly have been familiar from his childhood in Port Chalmers on the Otago harbour. The family home was near the Carey’s Bay graveyard where Culbert’s maternal great-grandfather, Captain Alexander Rae, is buried; Bill and Pip Culbert’s son Rae is named after this ancestor. In the Culberts’ Putney house is a maritime painting by Nicholas Cammillieri of the brigs Aurora and Dasher entering Malta Harbour. Both vessels were from Kirkcudbright in Scotland, and miniature buoys from them used to hang in Culbert’s grandparents’ house.

There is a tension in Blackball to Roa, between the work as a stand- alone art object, the significance of which is found principally within art-historical discourse, and Virilio’s “watchful archaeology”, which might locate the work’s signification within a complex of recovered or reconstituted memories activated by an old kero tin. Of course few if any of these memories will be accessible to to most viewers of the work. And yet the presence of narrative haunts the old tin of Blackball to Roa – perhaps the memory of the rubbish that used to spill down the slope to the ‘Back Beach’ at Port Chalmers. Or, to locate the work’s geographical provenance and narrative more exactly, somewhere on the West Coast road between Blackball and Roa where, in 1978, there were a number of old coal mines and, no doubt, plenty of tips with empty kero tins on them (if they hadn’t already been recycled, with the tops cut off and wire handles fitted like the ones I remember from childhood). The word ‘redolent’ seems stuffy and old fashioned when used to describe Culbert’s work, and yet it usefully subverts a narrative-averse account of the aesthetic impact of artworks. The marvellous and even dazzling aesthetic presence of many of his major works is undeniable – they delight and amaze in ways that seem largely self-sufficient. And yet an installation such as Voie lactée (Milky Way) at Tournus in 1990, even with its inbuilt art-historical reference to the erotic Milky Way element in the upper part of Duchamp’s The Large Glass (The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even) (1915–23), is redolent of what Culbert called conditions. Such conditions at Tournus might include the fact that the location was the refectory of the Abbaye Saint-Philibert, to which the blue enamel milk jugs could well have belonged. The fluorescent tubes seem to spill their milky light over the flagstones from the jugs. At night, the Milky Way seen through the arched windows might pour its starlight on to the floor. The installation as a whole becomes a night sky flooded with milky stars and projected into the refectory through its windows.

Bill Culbert Blackball to Roa 1978. Kerosene tin and fluorescent tube. Photo: Bill Culbert. Courtesy Auckland University Press and the Estate of Bill and Pip Culbert

Another major floor-based installation of neon tubes and containers is Pacific Flotsam (2007), originally made for Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art, subsequently exhibited at the Govett Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, and acquired by Christchurch Art Gallery in 2008. The image of this work on the Gallery’s website shows a topographic view – not the one experienced by viewers in a gallery, who would look at it laterally as if from the margins of an expanse of water. But the top- down viewpoint of the museum’s photograph is redolent in several ways: it conveys the density of a floating island of plastic rubbish on jostling crosscurrents of light; and it matches the detailed topographic installation map drawn by Culbert, which is in itself a calligraphic narrative or storyboard.

Bill Culbert Pacific Flotsam 2007. Fluorescent light, electric wire, plastic bottles. Purchased 2008. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, reproduced with permission and courtesy the Estate of Bill and Pip Culbert

There’s a story behind one of Culbert’s best-known images, a glass of red wine lit by sunlight and casting what appears to be the paradoxical shadow of a lightbulb Culbert made many versions of this, both as photographs and as a major installation. But all reflect to some degree the moment when, sharing an evening glass of eau-de-vie with friends at Croagnes, he noticed that his glass was refracting an image of the overhead lightbulb on to the table. This small congenial narrative detail is perhaps the most appropriate to recover from the décharge of memories associated with Bill Culbert, and with which to salute a great artist whose work was always hospitable to its conditions and their narrative traces

Bill Culbert Small Glass Pouring Light 1983. Serpentine Gallery, London, 1983. 25 verres bistrot, wine, Formica table, lampshades. Collection FNAC, Château d’Oiron. Photo: Bill Culbert. Reproduced courtesy Auckland University Press and the Estate of Bill and Pip Culbert